The David J. Sencer CDC Museum will re-open with new visitation protocols on January 2nd, 2026. All visitors must make advanced reservations. Walk-in visits are no longer permitted.

The following information is required while making reservations:

- Visitors to provide first, middle, and last name

Visitors 18 and over will also need to submit:

- Date of birth

- Citizenship (Select U.S. or non-U.S. citizen)

- Government-issued valid (not expired) REAL ID number or passport number

Bring confirmation email(s) for museum visit.

Teen Newsletter: December 2020 – Domestic HIV/AIDS

The David J. Sencer CDC Museum (CDCM) Public Health Academy Teen Newsletter was created to introduce teens to public health topics. Each month will focus on a different public health topic that CDC studies. Newsletter sections: Introduction, CDC’s Work, The Public Health Approach, Special Feature, Out of the CDC Museum Collection, and Activities.

Be sure to join our live Newsletter Zoom on January 5, 2021 at 8pm to vote on the public health topics for the March – December 2021 newsletters! Check out all the activities (digital scavenger hunt—Goosechase, Zoom, social media challenge, and Ask a CDCer) at the end of each newsletter. Join in on the fun and win some prizes! Also, be on the lookout for the recently added pre-Zoom Kahoot game that will be emailed the day of the Zoom.

HIV can affect anyone regardless of sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, sex, or age. However, certain groups are at higher risk for HIV and merit special consideration because of particular risk factors.

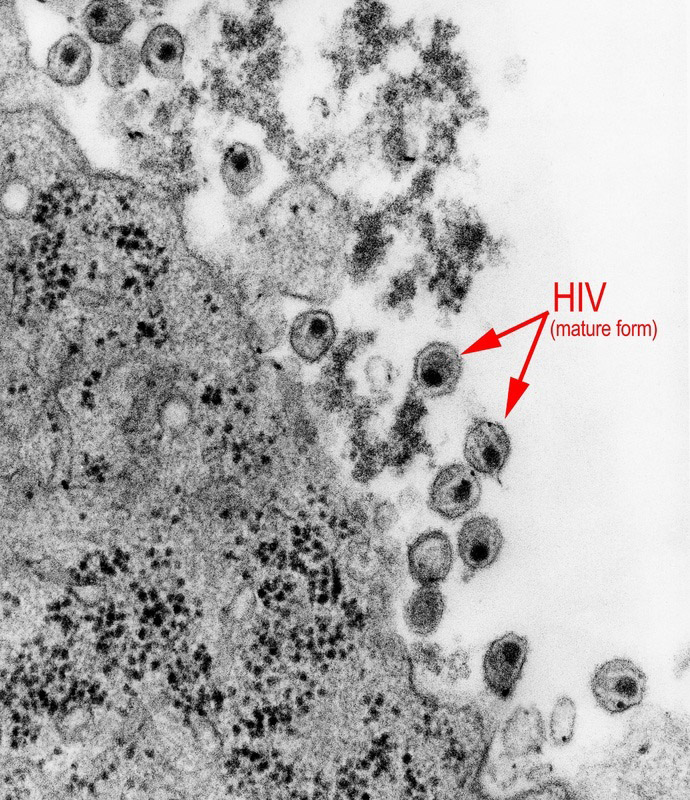

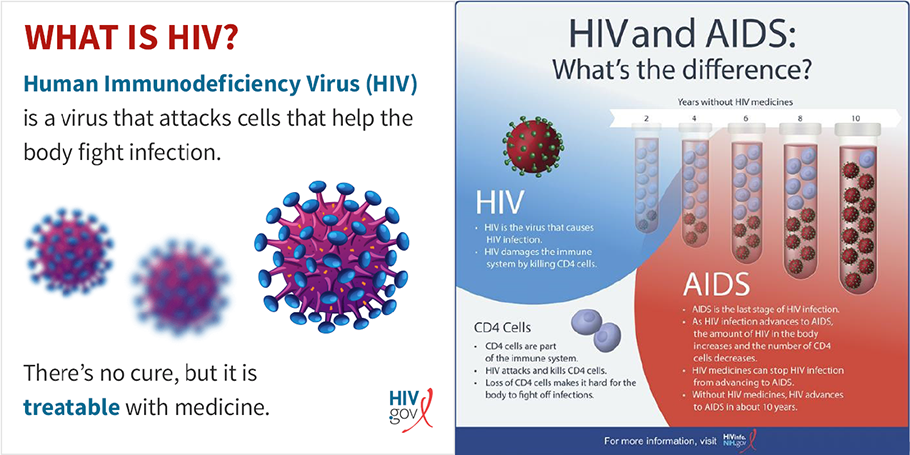

HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) is a virus that attacks the immune system by destroying CD4+ T cells, a type of white blood cell that is vital to fighting off infection. The virus is spread by contact with certain bodily fluids of a person with HIV, most commonly during unprotected sex (sex without a condom or HIV medicine to prevent or treat HIV), or through sharing injection drug equipment. A member of the genus Lentivirus, HIV is separated into two serotypes, HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is the most common type of HIV and accounts for 95% of all infections, whereas HIV-2 is relatively uncommon and less infectious.

If left untreated, HIV can lead to the disease AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). Some people have flu-like symptoms within 2 to 4 weeks after infection (called acute HIV infection). But some people may not feel sick during acute HIV infection. The only way to know if someone has an HIV infection is by getting tested.

There are currently three types of HIV tests. One is the nucleic acid test, or NAT, that looks for the actual virus in the blood and involves drawing blood from a vein. The test can either tell if a person has HIV or tell how much virus is present in the blood (known as an HIV viral load test). While a NAT can detect HIV sooner than other types of tests, this test is very expensive and not routinely used for screening individuals. The second is an antigen/antibody test that looks for both HIV antibodies and antigens. Antibodies are produced by your immune system when you’re exposed to viruses like HIV. Antigens are foreign substances that cause your immune system to activate. If you have HIV, an antigen called p24 is produced even before antibodies develop. This lab test involves drawing blood from a vein. There is also a rapid antigen/antibody test available that is done with a finger prick. And finally, there is an HIV antibody test. It only looks for antibodies to HIV in your blood or oral fluid. In general, antibody tests that use blood from a vein can detect HIV sooner after infection than tests done with blood from a finger prick or with oral fluid. Most rapid tests and the only currently approved HIV self-test are antibody tests. More information on HIV testing.

The human body cannot get rid of HIV and no effective HIV cure exists. So, once you have HIV, you have it for life. However, by taking HIV medicine (called antiretroviral therapy or ART), people with HIV can live long and healthy lives and prevent transmitting HIV to their sexual partners. In addition, there are effective methods to prevent getting HIV through sex or drug use, including pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). Prophylactic treatment for any disease means to treat for the disease after potential exposure. Be sure to do this month’s digital scavenger hunt activity for a guided exploration of the pre- and post-exposure medications!

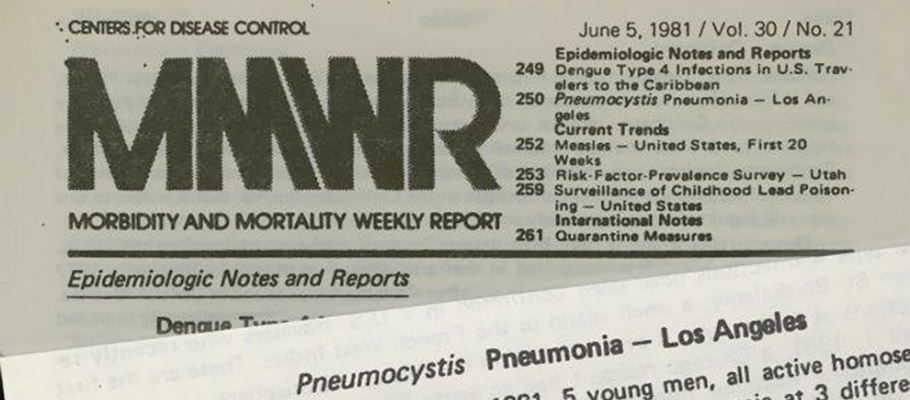

CDC has been involved in HIV/AIDS work since the first documentation of the disease. On June 5, 1981, CDC published an article in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR): Pneumocystis Pneumonia–Los Angeles. The article described cases of rare lung infection, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in five young, white, previously healthy gay men in Los Angeles, CA. This report marks the first reporting of what will later become known as AIDS. CDC has diligently worked on HIV/AIDS since this first reporting in 1981.

Curious about what it was like to work on HIV/AIDS during those first years? Visit CDC Museum’s AIDS Global Health Chronicles page to hear directly from the CDCers who worked on HIV/AIDS.

Today CDC’s vast work on HIV/AIDS is divided into two programs: domestic HIV/AIDS, meaning in the United States, and global HIV/AIDS. This month’s newsletter focuses only on domestic work. If you are curious about global HIV/AIDS, join us for this newsletter’s Zoom on 1/05/21 at 8pm EST to vote for the topic to be covered in 2021! Your vote truly matters.

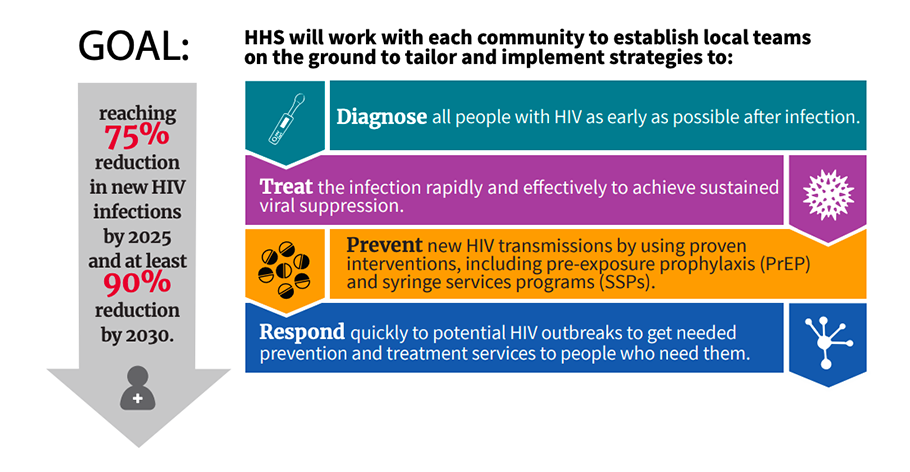

In 2018 the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) launched Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America. The initiative aims to reduce new HIV infections in the U.S. by 90% by 2030. CDC works closely with state and local governments, people with and at risk for HIV, as well as federal partners to coordinate efforts on expanding the use of the highest-impact HIV prevention strategies: Diagnose; Treat; Prevent; and Respond. The Plan focuses first on 50 local areas that account for more than half of the new HIV diagnoses (48 counties; San Juan, Puerto Rico; and Washington, D.C.) Click to explore an interactive map of the 50 areas.

Public health problems are diverse and can include infectious diseases, chronic diseases, emergencies, injuries, environmental health problems, as well as other health threats. Regardless of the topic, we take the same systematic, science-based approach to a public health problem by following four general steps. Let’s explore a case study on HIV/AIDS using this approach.

1. Surveillance (What is the problem?)

In public health, we identify the problem by using surveillance systems to monitor health events and behaviors occurring among a population.

CDC collects, compiles, and analyzes information on HIV activity year-round in the United States through several reporting systems, but this case study will focus on data reported through the Enhanced HIV/AIDS Reporting System (eHARS).

HIV is a notifiable disease, meaning doctors’ offices, clinics, and all testing facilities are required to report new cases of HIV infection to state health departments through the eHARS system. This web-based system assists health departments with reporting, data management, analysis, and transfer of data to CDC. CDC then analyses the data to look for clusters of new HIV cases, and to compare these data to rates of infection earlier in the year or past years to see if there are increases in numbers or a change in what type of population is being infected. These data are then provided back to each state for local programs to use, though some states do their data analyses. At times, if appropriate, CDC may send epidemiologists to investigate in the community, but more often CDC provides data analysis, advice called technical assistance, and provides funding for HIV prevention programs.

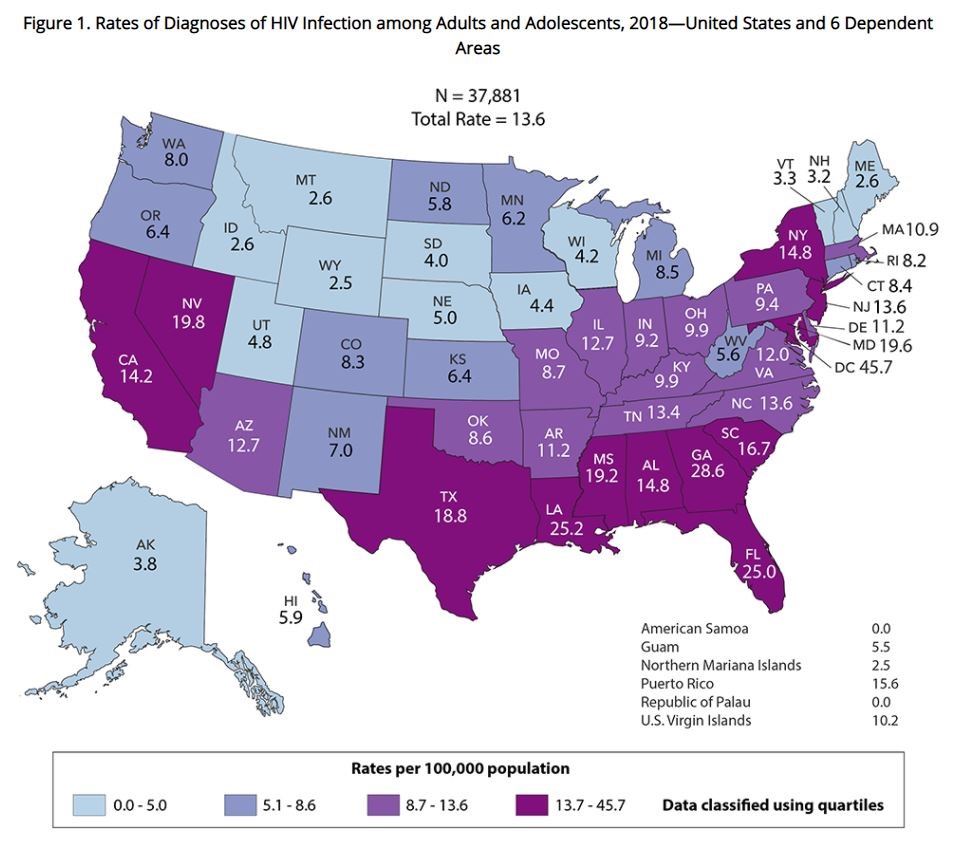

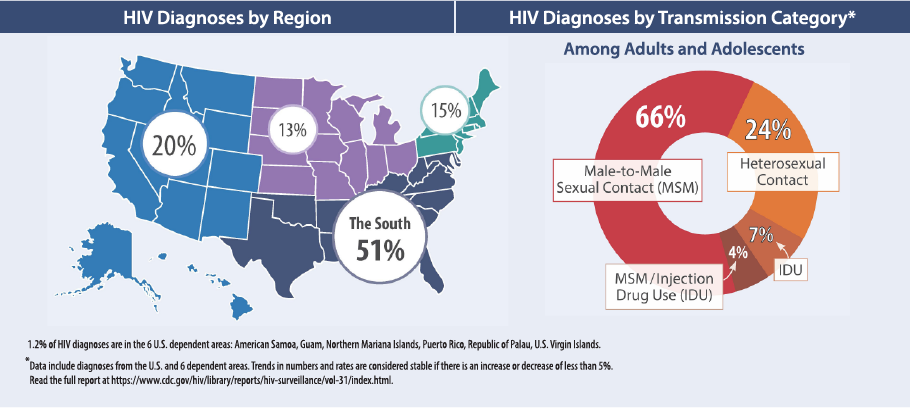

Data from eHARS is compiled into HIV surveillance reports—for example, the number and population rates of HIV diagnoses, the number of people living with HIV, and the number of people who are receiving HIV medical care. The report provides information like the map below, which shows the rate of HIV infections per 100,000 persons in 2018.

The data is also analyzed according to age, race/ethnicity, sex and transmission category. Below you can see the 2018 data broken down according to race/ethnicity. From the larger graph we see that the Black/African American population has the highest incidence. Also note that the smaller inset is due to the difference in scale on the Y axis.

Below is the breakdown of data according to age. From the graph we can see highest incidence was within the 25-34 years age group, and that for several other age groups the rates decreased slightly.

Analyzing data helps CDC and other public health entities create programs for the populations most at risk for HIV infection.

2. Risk Factor Identification (What is the cause?)

After we’ve identified the problem, the next question is, “What is the cause of the problem?” For example, are there factors that might make certain populations more susceptible to disease, such as something in the environment or certain behaviors that people are practicing?

In this step, we, the collective public health community, consider why people in this community are testing positive – are they doing anything that is putting them at risk? For example, in one community a cluster of new HIV cases was detected in a homeless encampment. The investigation also revealed that a medical clinic nearby offered PrEP for HIV prevention. Earlier in this newsletter, you learned that PrEp, if taken every day, provides a 99% protection against HIV, so it could be easy to assume that the HIV infections in this community should be low. However, investigations into this cluster revealed that persons living in the area were often afraid to leave their tents or the encampment area for fear of their possessions being taken, either by others living nearby or in a city-mandated clean up. For HIV prevention this is problematic for several reasons. First, a person must be evaluated by a medical professional before being prescribed PrEP and the PrEP medications must be taken daily. If persons are afraid of leaving their areas and are afraid that their possessions may be taken, they may not be willing to go see the medical professionals for the initial evaluation, and they could have trouble keeping their supply of pills.

3. Intervention Evaluation (What works?)

Once we’ve identified the risk factors related to the problem, we ask, “What intervention works to address the problem?” We look at what has worked in the past in addressing this same problem and if a proposed intervention makes sense with our affected population.

In our scenario of persons who are homeless, local or state organizations may consider what ways they could support persons who are homeless. Examples of programs they could evaluate are ways in which to bring medical professionals to the encampment, housing options, or ways to help these individuals keep their medication supplies safe. Part of the evaluation of intervention strategies would involve determining funding for possible programs.

4. Implementation (How did we do it?)

In the last step, we ask, “How can we implement the intervention? Given the resources we have and what we know about the affected population, will this work?”

In this step, CDC would work with partner agencies or groups by funding programming such as mobile HIV testing groups, mobile medical clinics, and prescription lockers to allow persons experiencing homelessness to have a safe place to store ART or PrEP medications.

Much of the work CDC does is to provide data for local groups to implement in their communities. Read this article of how Boston University’s School of Social work implemented mobile medical teams across the U.S. to serve persons who are homeless and have HIV.

As you can see, using The Public Health Approach helps public health professionals identify a problem, find out what is causing it, and determine what solutions/interventions work.

This month’s special feature highlights CDC’s work in addressing stigma, a degrading attitude that discredits a person or a group because of an attribute such as an illness, deformity, color, nationality, religion etc. HIV stigma is negative attitudes and beliefs about people with HIV. It is the prejudice that comes with labeling an individual as part of a group that is believed to be socially unacceptable by some. Negative thoughts do not always come from other people, though. In internalized stigma, people with HIV experience negative feelings or thoughts about themselves due to their HIV status. Almost 8 in 10 adults with HIV receiving HIV medical care in the United States report feeling internalized HIV-related stigma, according to a CDC study. Internalized stigma can lead to depression, isolation, and feelings of shame, and can affect an individual’s ability to continue taking HIV medication.

To help combat HIV stigma, CDC created practice stigma scenarios and stigma pledge cards – opportunities for each of us to speak openly about HIV and to stand up to reduce stigma. These colorful cards are meant to be used to openly pledge support for persons with HIV.

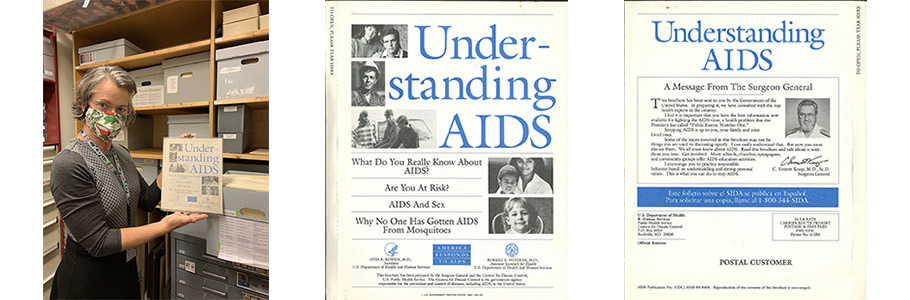

CDC Museum’s Historic Collection has many objects and documents related to early days of work on what we now call HIV/AIDS. The CDC Museum Collections Manager Mary Hilpertshauser (contractor) shares her favorite HIV/AIDS related item in collection – a booklet that was mailed to every U.S. address in 1988 to increase understanding of the disease and to reduce stigma. The “Understanding AIDS” pamphlet made public health history in 1988 because it was mailed to every household in the United States. According to several national polls, approximately 126 million copies were distributed, reaching at least 60 percent of the population.

“Understanding AIDS” was a pioneering effort, as it was the first government publication aimed at the general public that contained all the essential facts about AIDS. It used explicit language to describe HIV Infection and AIDS as pioneered in the “Surgeon General’s Report on Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome.” It allowed people to start talking more openly about sex and sexual orientation. Read a CDC Morbidity and Mortality Report article announcing the mailer.

In the image above, Mary displays the mint condition, never-opened booklet safely preserved in the CDC Museum Historic Collection.

New prizes available for the December newsletter activities! All winners will be announced 1/05/21 during the Zoom – see individual deadlines below, as applicable.

*The following newsletter activities: Scavenger Hunt, Zoom, and Social Media Challenge are available for your participation anytime – even after deadlines. To be eligible for prizes you must complete activities by the deadline.

Scavenger Hunt

Scavenger Hunt

Scavenger Hunt

Teen Talk

Teen Talk

Teen Talk

Social Media Challenge #CDCTeenNewsletter

Social Media Challenge #CDCTeenNewsletter

Social Media Challenge #CDCTeenNewsletter

Ask a CDCer

Ask a CDCer

Ask a CDCer

Want to do a fun digital scavenger hunt?

Time: ~20 min to complete

Complete all missions by 01/04/21 11pm EST, for prize drawing.

See below for more details.

Scavenger Hunt

Want to do a fun digital scavenger hunt?

Time: ~20 min to complete

Complete all missions by 01/04/21 11pm EST, for prize drawing.

See below for more details.

Want to learn more from CDCers who work on domestic (U.S.) HIV/AIDS?

Join us for an exclusive Zoom on 01/05/21 at 8pm EST.

Advance registration required. All who register by or on 01/04/21 11pm will be entered into a prize drawing.

Watch the domestic HIV Teen Talk.

Teen Talk

Want to learn more from CDCers who work on domestic (U.S.) HIV/AIDS?

Join us for an exclusive Zoom on 01/05/21 at 8pm EST.

Advance registration required. All who register by or on 01/04/21 11pm will be entered into a prize drawing.

Watch the domestic HIV Teen Talk.

Help us spread to word about the Teen Newsletter! Encourage your followers to sign up for the CDC Museum Teen Newsletter using this link: https://tinyurl.com/cdcm-teen

Submit a screenshot of your post by 01/04/21 11pm EST to be entered into a prize drawing.

Click here for instructions and to submit a screenshot of your post.

Social Media Challenge #CDCTeenNewsletter

Help us spread to word about the Teen Newsletter! Encourage your followers to sign up for the CDC Museum Teen Newsletter using this link: https://tinyurl.com/cdcm-teen

Submit a screenshot of your post by 01/04/21 11pm EST to be entered into a prize drawing.

Click here for instructions and to submit a screenshot of your post.

Do you have a question for a CDCer who works on domestic (U.S.) HIV/AIDS?

Submit your question for the HIV/AIDS experts who will be joining the Zoom on 01/05/21 at 8pm EST.

If your question is selected, you will get a shout out on the live Zoom and a prize.

Please do not submit questions that are answered by reading this newsletter.

Submit your question(s) by 01/04/21 11pm EST.

Ask a CDCer

Do you have a question for a CDCer who works on domestic (U.S.) HIV/AIDS?

Submit your question for the HIV/AIDS experts who will be joining the Zoom on 01/05/21 at 8pm EST.

If your question is selected, you will get a shout out on the live Zoom and a prize.

Please do not submit questions that are answered by reading this newsletter.

Submit your question(s) by 01/04/21 11pm EST.

CDCM PHA Teen Newsletter Scavenger Hunt

December 2020

Step 1: Download the GooseChase iOS or Android app

Step 2: Choose to play as a guest

Step 3: Enter game code – GZVE6B

Step 4: Enter password – CDC

Step 5: Enter your email as your player name (this is how we will contact you if you are the prize winner)

Step 6: Go to www.cdc.gov/hiv to complete your missions

Tips for Winning:

- All answers are found on the website, see Step 6.

- Open-ended answers and photo submissions are evaluated for accuracy.

- Complete all the missions by 01/04/21 11pm EST, to be entered into a drawing for a prize.

- Make sure to make your player name is your email.

Have fun!