The David J. Sencer CDC Museum will re-open with new visitation protocols on January 2nd, 2026. All visitors must make advanced reservations. Walk-in visits are no longer permitted.

The following information is required while making reservations:

- Visitors to provide first, middle, and last name

Visitors 18 and over will also need to submit:

- Date of birth

- Citizenship (Select U.S. or non-U.S. citizen)

- Government-issued valid (not expired) REAL ID number or passport number

Bring confirmation email(s) for museum visit.

Teen Newsletter: Opioids

July 2022

The David J. Sencer CDC Museum Public Health Academy Teen Newsletter introduces teens to different public health topics that CDC studies. This newsletter provides an Introduction, explains CDC’s Work, breaks down the topic using the Public Health Approach, and gives you a behind the scenes look at historical items Out of the CDC Museum Collection.

Opioids are a class of drugs used to reduce pain. Opioids include the illegal drug heroin, synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, and pain medications available legally by prescription. Prescription opioids are generally safe when taken for a short time and as directed by a doctor, but because they produce euphoria in addition to pain relief, they can be misused and have addiction potential.

Heroin

Heroin

Fentanyl

Fentanyl

Prescription Opioids

Prescription Opioids

Heroin is an illegal opioid. On average, 36 people die every day from an overdose death involving heroin in the United States.

From 2019 to 2020, the heroin-involved death rates decreased by 7%.

Heroin is an illegal opioid. On average, 36 people die every day from an overdose death involving heroin in the United States.

From 2019 to 2020, the heroin-involved death rates decreased by 7%.

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid pain reliever. It is many times more powerful than other opioids and is approved for treating severe pain, typically advanced cancer pain. Illegally made and distributed fentanyl has been on the rise in several states.

From 2019 to 2020, the synthetic opioid-involved death rates (excluding methadone) increased by 56%.

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid pain reliever. It is many times more powerful than other opioids and is approved for treating severe pain, typically advanced cancer pain. Illegally made and distributed fentanyl has been on the rise in several states.

From 2019 to 2020, the synthetic opioid-involved death rates (excluding methadone) increased by 56%.

Prescription opioids can be prescribed by doctors to treat moderate to severe pain but can also have serious risks and side effects.

Common types are oxycodone (OxyContin), hydrocodone (Vicodin), morphine, and methadone.

From 2019 to 2020, the prescription opioid-involved death rates increased by 17%.

Prescription opioids can be prescribed by doctors to treat moderate to severe pain but can also have serious risks and side effects.

Common types are oxycodone (OxyContin), hydrocodone (Vicodin), morphine, and methadone.

From 2019 to 2020, the prescription opioid-involved death rates increased by 17%.

Overdoses are the leading injury-related cause of death in the United States and appear to have accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The rise in opioid-related deaths has been classified into three waves: the first wave began in the 1990’s, with prescription opioid deaths increasing. The second wave began in 2010, with rapid increases in overdose deaths involving heroin. The third and present wave began in 2013, with significant increases in overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids, particularly those involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl. A majority of people who end up using fentanyl do not purposely purchase or use it at first; fentanyl is often used as an additive to other drugs, and these people often use it unknowingly. Since even a miniscule dose of fentanyl can be lethal, its prominent presence in other drugs can easily cause accidental overdoses. The market for illicitly manufactured fentanyl continues to change, and it can be found in combination with heroin, counterfeit pills, and cocaine.

From 1999–2020, more than 564,000 people died from an overdose involving any opioid, including prescription and illicit opioids.

The number of drug overdose deaths increased by nearly 30% from 2019 to 2020 and has quintupled since 1999. Nearly 75% of the 91,799 drug overdose deaths in 2020 involved an opioid.

Opioid abuse disorder (OUD) is a problematic pattern of opioid use that causes significant impairment or distress. OUD can affect anyone – regardless of race, sex, income level, or social class. OUD significantly contributes to overdose deaths among people who use illicit opioids or misuse prescription opioids. Opioids—mainly synthetic opioids like illicitly manufactured fentanyl—are currently the main cause of drug overdose deaths. For every drug overdose that results in death, there are many more nonfatal overdoses, each one with its own emotional and economic toll. OUD and overdose deaths continue to be a major public health concern in the United States, but they are preventable.

CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, or NCIPC, is the center responsible for addressing the rise in opioid-related overdoses and deaths.

CDC is committed to fighting the opioid overdose epidemic and supporting states and communities as they continue work to identify outbreaks, collect data, respond to overdoses, and provide care to those in their communities. CDC improves public safety to improve opioid prescriptions, educating the public and empowering people to make safe choices, and collaborating with first responders like paramedics and police to improve communication between public health and public safety.

CDC’s Work is Guided by Six Principles and Five Strategic Priorities to Address the Overdose Crisis

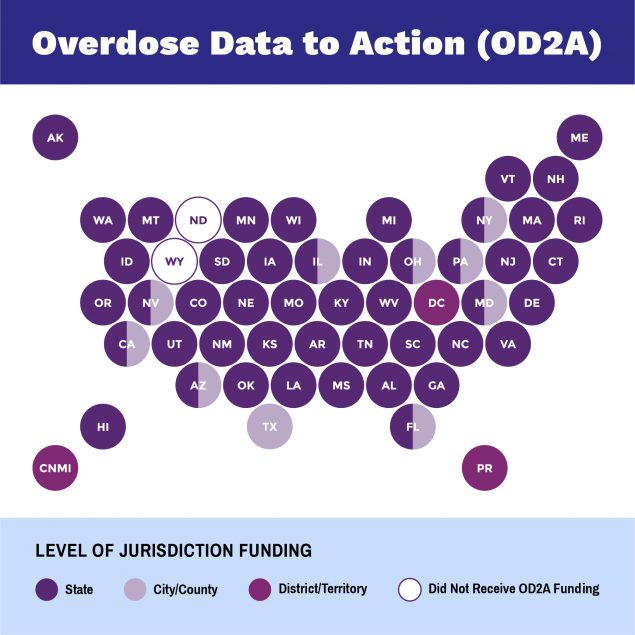

NCIPC’s Overdose Data to Action (OD2A) contributes to CDC’s efforts to prevent opioid overdoses. OD2A supports 66 state, territorial, county, and city health departments in obtaining high quality, comprehensive, and timely data on overdose morbidity and mortality and uses those data to inform prevention and response efforts.

While public health efforts have brought attention to drug addiction as a disease and have improved access to substance use disorder treatment and services, many health inequities have not been addressed. Health inequities can contribute to worsening opioid overdose rates, especially among groups that have been disadvantaged by reduced economic stability, experiencing disabilities, homelessness, mental health conditions, or incarceration, or are from racial, ethnic, sexual, and sexual minority groups. NCIPC continues to work with the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) to investigate the literature available on this topic, as well as tools and resources which could provide guidance for health departments on addressing drug overdose through the use of a health equity lens.

Other centers at CDC that are working to address the opioid overdose epidemic include:

Youth opioid use is linked to risky behaviors like not using a condom and that can lead to HIV, STDs, and unintended pregnancy.

Learn more about NCHHSTP’s efforts in The Public Health Approach section below.

Public health problems are diverse and can include infectious diseases, chronic diseases, emergencies, injuries, environmental health problems, as well as other health threats. Regardless of the topic, we take the same systematic, science-based approach to a public health problem by following four general steps.

For ease of explaining and understanding the public health approach for this public health problem (opioids), let’s focus on opioid misuse among adolescents and how the CDC is addressing the problem.

- Surveillance (What is the problem?). In public health, we identify the problem by using surveillance systems to monitor health events and behaviors occurring among a population.

To gather data on opioid use among adolescents, CDC uses the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS). YRBSS monitors six categories of health-related behaviors that contribute to the leading causes of health and disability among youth and adults, including alcohol and other drug use.

Did you know that nearly 1 in 7 students reported ever misusing prescription opioids, and approximately 1 in 14 students reported misusing them during the past 30 days?

- Risk Factor Identification (What is the cause?). After we’ve identified the problem, the next question is, “What is the cause of the problem?” For example, are there factors that might make certain populations more susceptible to diseases, such as something in the environment or certain behaviors that people are practicing?

Adolescence is a critical high-risk period for the initiation of substance use (i.e., opioid misuse) and progression to addiction. Teens with substance use disorders experience higher rates of physical and mental illnesses and diminished overall health and well-being. Research shows that behaviors and experiences related to sexual behavior, high-risk substance use, violence victimization, and mental health contribute to substantial morbidity in youth, including risk for HIV, STDs, and teen pregnancy. Data indicate that these four risk behaviors co-occur, and some young people may experience more than one risk behavior. Primary prevention of high-risk substance use, like opioid misuse, among youth presents an important opportunity to prevent infectious diseases and protect the mental and physical health of adolescents.

Are there certain adolescents that are more at-risk for opioid misuse?

- Does it matter where you live?

The 2019 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey PowerPoint Slides shows a map of the United States with the heading “Percentage of High School Students Who Ever Took Prescription Pain Medicine Without a Doctor’s Prescription or Differently Than How a Doctor Told Them to Use It*”. There is an asterisk indicating that drugs such as codeine, Vicodin, OxyContin, Hydrocodone, and Percocet were counted. The coloration of each state varies from a light blue to an intense navy blue as the percentage of high school students abusing prescription pain medicine increases. Several states in the northern half of the contiguous United States are shown in white to indicate a lack of data.

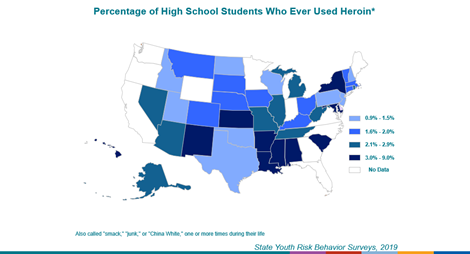

The 2019 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey PowerPoint Slides shows a map of the United States with the heading “Percentage of High School Students Who Ever Used Heroin*”. There is an asterisk indicating other names for heroin, “smack”, “junk”, or “China White”. The coloration of each state varies from a light blue to an intense navy blue as the percentage of high school students who have ever used heroin increases. Several states in the northern half of the contiguous United States are shown in white to indicate a lack of data.

- What about your sex?

Compared with females, males had a significantly higher prevalence of lifetime use of heroin (2.3% versus 1.0%). Compared with males, females had a significantly higher prevalence of current prescription opioid misuse (8.3% versus 6.1%) and lifetime prescription opioid misuse (16.1% versus 12.4%).

The Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary 7 Trends Report 2009-2019 shows a bar chart titled “Percentage of High School Students Who Had Ever Misused Prescription Opioids, by Sex and by Race/Ethnicity, United States, YRBS, 2019”. Individual bars display the percentage of teens who have misused prescription opioids in their lifetime for (from top to bottom) all teens, male teens, female teens, White teens, Black teens, and Hispanic teens. The numerical percentage is displayed in white at the right end of each bar. In 2019, 14.3 percent of all teens had ever misused prescription opioids, and more female students than male students had ever misused prescription opioids.

- Is your race/ethnicity a factor?

The prevalence of current prescription opioid misuse was significantly lower among White students (5.5%) compared with Black (8.7%) or Hispanic students (9.8%).

| The Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary 7 Trends Report 2009-2019 shows a bar chart titled “Percentage of High School Students Who Had Misused Prescription Opioids During The Past 30 Days, by Sex and by Race/Ethnicity, United States, YRBS, 2019”. Individual bars display the percentage of teens who have misused prescription opioids in the past 30 days (from top to bottom) all teens, male teens, female teens, White teens, Black teens, and Hispanic teens. The numerical percentage is displayed in white at the right end of each bar. In 2019, about 7 percent of high school students, more female students than male students, and more Black and Hispanic than White students had misused prescription opioids during the past 30 days. |

- Does your sexual identity play a role?

Students who identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual had a higher prevalence of all studied substance use behaviors, except binge drinking, compared with students who identified as heterosexual. Similarly, students who identified as not sure of their sexual identity also had higher prevalence of approximately half of the substance use behaviors compared with heterosexual students, including current prescription opioid misuse, lifetime heroin use, and lifetime prescription opioid misuse.

| The 2019 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey PowerPoint Slides shows a bar chart with the heading “Percentage of High School Students Who Ever Took Prescription Pain Medicine Without a Doctor’s Prescription or Differently Than How a Doctor Told Them to Use It* by Sexual Identity and ex of Sexual Contacts, 2019”. There is an asterisk indicating that drugs such as codeine, Vicodin, OxyContin, Hydrocodone, and Percocet were counted. From left to right the chart shows three sections. The first section shows one bar at 14.3 percent representing the total. The middle/second section shows three bars representing sexual identity and shows 12.7 percent for heterosexual, 23.9 percent for gay, lesbian or bisexual, and 19.1 percent for unsure. The third and final section shows three bars representing sex of sexual contacts and shows 16.6 percent for opposite sex only, 33.9 percent for same sex or both sexes, and 8.5 percent for no sexual contact. |

Students reporting prescription opioid misuse commonly indicated use of other substances and other studies conducted among adolescents have identified an association between substance use and sexual risk behaviors (i.e., ever having sex, having multiple sex partners, not using a condom, and pregnancy before the age of 15 years of age).

Other common risk factors for substance abuse and sexual risk behaviors include extreme economic deprivation (poverty, over-crowding); family history of the problem behavior, family conflict, and family management problems; favorable parental attitudes towards the problem behavior and/or parental involvement in the problem behavior; lack of positive parent engagement; association with substance using peers; alienation and rebelliousness; and lack of school connectedness.

- Intervention Evaluation (What works?). Once we’ve identified the risk factors related to the problem, we ask, “What intervention works to address the problem?” We look at what has worked in the past in addressing this same problem and if a proposed intervention makes sense with our affected population.

Teens Linked to Care (TLC) was a three-year pilot project to assess the feasibility of implementing integrated prevention strategies to address both substance use and sexual risk among youth in high-risk rural communities. The project was a collaboration between CDC’s Division of Adolescent and School Health under the National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, the CDC Foundation, the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, and three pilot sites: Scott County School District 1 (Austin, Indiana), The Brighton Center (Campbell County, Kentucky), and Portsmouth City Health Department (Portsmouth, Ohio). The goal of the pilot was to develop a framework for schools to address HIV, STD, teen pregnancy, and high-risk substance use (i.e., use of prescription, illicit, or injection drugs like opioids) among youth through education, primary prevention, and early detection screening.

- Implementation (How did we do it?). In the last step, we ask, “How can we implement the intervention? Given the resources we have and what we know about the affected population, will this work?”

Community engagement is the process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of those people. It is a powerful vehicle for bringing about environmental and behavioral changes that will improve the health of the community and its members. It often involves partnerships and coalitions that help mobilize resources and influence systems, change relationships among partners, and serve as catalysts for changing policies, programs, and practices.

Through the pilot initiative, CDC provided a school-centered approach in three communities to educate teens on the dangers of substance use and collaborated with local health departments to offer health screenings to identify those teens most at risk for HIV, sexually transmitted diseases, teen pregnancy and high-risk substance misuse (i.e., opioid misuse). Youth and community advisory boards were vital in the initiative. Critical to the project’s success were partners’ abilities to work closely with local communities, training local health providers and leveraging local resources to raise awareness about substance use.

The three pilot sites successfully implemented and developed strategies in several key areas, including:

- Developing new health education curricula reaching all students in their respective high schools that address prevention of HIV, STD, teen pregnancy, risky sexual behavior and substance use;

- Developing and distributing products to promote youth-friendly health services in order to increase access to HIV, STD, and substance use screening and testing, as well as other health services;

- Collaborating with local health departments to offer health screenings to identify those most at risk for HIV, STDs, teen pregnancy, and high risk substance use;

- Collecting data about student opinions and experiences with bullying at school, resulting in a review of school bullying policies due to the association between bullying and substance use;

- Producing anti-bullying and anti-opioid campaign videos to promote positive school climates where students feel safe from bullying and the risk of substance use; and

- Partnering with their communities’ drug-free coalitions to leverage resources and increase youth and adult knowledge in substance use and prevention.

Teal rectangular graphical element titled “Impact” with subheading “Of the students screened for risky substance use behavior through TLC:” and 2 icons showing results. The first on the left is an icon with a medical cross and male and female medical providers with the text “27% received brief intervention by a health care provider”. The second icon on the right is two pills with the text “25% were refereed to substance use treatment”.

TLC is addressing issues of substance use and risky sexual behavior before they reach crisis level, where an ounce of prevention now is worth a pound of cure later.

Future activities include developing a framework that integrates school-based strategies for the prevention of high-risk substance use and HIV, STDs, and teen pregnancy. The framework will be based on lessons learned during the pilot and will allow the three sites to move from implementation to outcomes (i.e., behavior change evaluation). This framework will also help inform a second phase of TLC where it could be expanded to additional rural schools and modified for large urban areas with communities that have youth that are at high risk for substance use.

Using The Public Health Approach helps public health professionals identify a problem, find out what is causing it, and determine what solutions/interventions work.

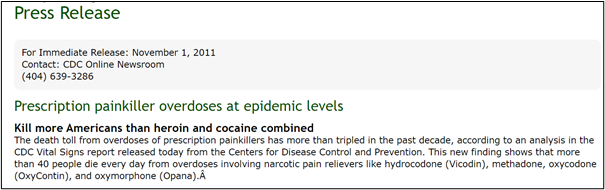

This month’s Out of the CDC Museum Collection features items from November 1, 2011. First is the main page of a CDC Vital Signs report and next is a snippet of a CDC press release highlighting that report. Both historical items highlight that prescription painkiller overdoses were at epidemic levels, with 1 in every 20 people reporting nonmedical use of prescription painkillers in 2010.

Vital Signs is a CDC report that appears on the first Tuesday of the month as part of the CDC journal Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, or MMWR. The report provides the latest data and information on key health indicators (i.e., obesity, tobacco use, prescription drug overdose, HIV, alcohol use, teen pregnancy, asthma, food safety).

A dark silhouette of a human body, with sparse details in a light brown outlining the location and shape of major organs, stands as the background for three opioid facts presented in a tan serif font with one basic purple illustration placed alongside each fact. The infographic notes nearly 15,000 overdose deaths per year and the use of prescription painkillers for nonmedical reasons by 1 in 20 people every year. The final included fact indicates that enough prescription painkillers were prescribed in 2010 to medicate every American adult around-the-clock for a month.

The header and first paragraph of a November 1, 2011, CDC Online Newsroom press release are shown. The title reads, “Prescription painkiller overdoses at epidemic levels,” and a subtitle reads, “Kill more Americans than heroin and cocaine combined.” The included first paragraph expounds, “The death toll from overdoses of prescription painkillers has more than tripled in the past decade, according to an analysis in the CDC Vital Signs report released today from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This new finding shows that more than 40 people die every day from overdoses involving narcotic pain relievers like hydrocodone (Vicodin), methadone, oxycodone (OxyContin), and oxymorphone (Opana).”

The November 1, 2011, CDC Vital Signs report and the associated press release reflected a pivotal point in the national response to the opioid epidemic. Since the release of the report, a decline in national opioid prescribing rates has been noted in the National Health Statistics Reports [640 KB, 12 pages]. The decreasing trend starting in 2010–2011 may be related to several factors: decreasing volume of prescription opioids; the hundreds of local, state, and federal programs that were implemented with the goal of changing prescribing practices; and prescription drug monitoring programs. Many of these interventions were implemented partially in response to the alarming incidence of opioid overdose publicized by the November 1, 2011, press release and, by extension, the press release itself.