About

The Miner Health Program Strategic Agenda defines the program's purpose and approach over its first decade.

Introduction and Purpose

What is the Miner Health Program? Why is it needed?

The Miner Health Program (MHP) has recently been established as a long-term, systematic effort to understand and improve the health and well-being of all miners through focused integration of research, transfer of findings, evaluation, and community engagement. The MHP is part of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Mining Program, whose mission is to eliminate mining fatalities, injuries, and illnesses through relevant research and impactful solutions.

Section 2 of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 states the following:

The Congress declares it to be its purpose and policy . . . to assure so far as possible every working man and woman in the Nation safe and healthful working conditions and to preserve our human resources . . . by exploring ways to discover latent diseases, establishing causal connections between diseases and work in environmental conditions, and conducting other research relating to health problems, in recognition of the fact that occupational health standards present problems often different from those involved in occupational safety [DOL 1970].1

This portion of the mandate highlights the fundamental need for the United States to approach the improvement of occupational health in an expansive and comprehensive manner.

Research shows that the chronic disease burden among adults in the United States disproportionately affects some people more than others. With some differences in relation to age and sex, 60% of American adults have at least one chronic health condition, 42% have multiple conditions, and nearly one in 10 live with five or more chronic conditions [Buttorff et al., 20172]. Of the $3.3 trillion that the U.S. spends on health care annually, 90% is directed toward individuals with chronic and mental health conditions [CDC, 2019]. We know that that burden of disease is associated with social determinants of health (SDOH) [Schultz & Northridge, 20043]. While work environments and factors are included in SDOH, work largely has been ignored in health inequities research [Anhonen, Fujishiro, Cunningham, & Flynn, 20184]. We know that some workers are exposed to higher-risk environments; yet, less understood is how disease burden may be disproportionately distributed across industry and occupation [Hege et al., 20185; Lingard & Turner, 20176].

Specific to the mining industry, much is known about injuries and injury-related miner fatalities due to robust regulatory reporting requirements overseen by the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) and established injury surveillance systems. However, with few exceptions, such as the respiratory disease burden in coal miners, there continues to be an insufficient understanding of the health of the broader mine worker population, how it has changed over time, and how it varies regionally or within sectors and commodities of mining. From these data, important questions emerge in relation to miner health:

- Are the prevalence and impacts of chronic disease among miners different from those of the general working population?

- Are miners and their employers subject to similar relative costs as the overall population?

- How can organizational and physical work environments be designed to reduce health hazard exposures and burdens, thereby improving mine worker health, well-being, and performance?

The concept of conducting research related to miner health is not new to NIOSH; however, the coordination of these and future expanding efforts is a new approach. At its most basic level, the MHP aims to develop, implement, and maintain a coordinated, comprehensive approach to conducting research related to miner health and workplace exposures; understand the role of work and non-work factors; and transfer findings to the mining community and associated stakeholders in the form of guidance, interventions, technology, and in practices and procedures.

Implementing this new approach begins with collaboratively developing a shared vision for the MHP based on available miner health and exposure data. This agenda serves as a roadmap for coordinating and guiding NIOSH activities that address miner health and well-being. This agenda will continue to evolve over time as we partner with stakeholders and continue to collect and synthesize surveillance, research, and evaluation data. Ultimately, only a coordinated, systematic approach and enduring partnerships with stakeholders will maximize the MHP's impact on miner health.

Characterizing Health and Well-Being

The World Health Organization defines health as a "state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity" [WHO 2006]. The Miner Health Program embraces this definition of health and envisions improved well-being for the entire mining population.

In partnership with the RAND Corporation, the NIOSH Total Worker Health® (TWH) program conducted a comprehensive review to develop a framework definition for worker well-being that is as follows:

. . . an integrative concept that characterizes quality of life with respect to an individual's health and work-related environmental, organizational, and psychosocial factors. Well-being is the experience of positive perceptions and the presence of constructive conditions at work and beyond that enables workers to thrive and achieve their full potential [Chari et al. 2018].7

The MHP will use this framework to better characterize miners' health experiences and potential risk-factors, quality of life, and ability to work and retire with function. This integrated approach creates opportunities to evaluate the MHP using several validated metrics for measuring health utility, such as disability- or quality-adjusted life year (DALY/QALY). Monitoring the physical and mental health status, disease burden, and workplace exposures of miners enables direct and indirect evaluation of program impacts via metrics including surveillance data, health care spending, and workers' compensation experience.

Mission, Vision, and Values

The mission, vision, and values of the Miner Health Program have been informed by conversations, presentations, and meetings between mining stakeholders and NIOSH. In simple terms, the mission affirms why the programmatic effort is being undertaken. The vision lays out a picture of the future and helps initiate the criteria for establishing priorities. Lastly, the values underlie and establish the foundation by which the plan is to be executed. As the MHP evolves, new elements will be introduced or reformulated to ensure relevance toward advancing miner health.

Mission, Vision, and Values

- The Miner Health Program's Mission is to identify, develop, and promote health solutions that maximize miner protection, minimize harmful exposures, and prevent disease.

- This mission will be accomplished by achieving our Vision of sustained health and well-being for all miners throughout their working years and retirement.

- Successful application of the mission and vision will demonstrate the Values of service, honesty, evidence, communication, and utility throughout the Miner Health Program.

The core values of the Miner Health Program help guide how the program goes about accomplishing its mission, and they help strengthen stakeholder commitment to this effort by instilling a shared purpose. These values are described below.

Service

The work and research conducted is a public service directed at benefiting the health and well-being of miners and is not motivated by self-interest or promotion.

Honesty

Our research is open, transparent, and collaborative so as to ensure trust and credibility.

Evidence-based

The judgement and decisions we make are informed by and based on sound science, evidence, reason, and an acknowledgment of the uncertainty inherent within evidence-based findings.

Communication

We engage in and listen to all relevant opinions before clearly articulating direction, findings, or feedback.

Utility

The products of the Miner Health Program are of high quality, have direct application, and can be measured for effectiveness, satisfaction, usefulness, or benefit.

Miner Health Program Design

The Miner Health Program intends to narrow the research-to-practice gap by integrating a comprehensive portfolio of laboratory and field research with translation science and transfer activities. Research, community engagement, and evaluation comprise the three core functions of the MHP. While research is the primary focus within NIOSH and the Mining Division, it alone is not sufficient to ensure long-term impacts and the health and well-being of miners. In addition to conducting strategic research, we also must continually engage collaboratively with mining stakeholders, learn from external surveillance and other sources of data, transfer research findings to the workplace through products and interventions, evaluate the processes and associated outcomes, and synthesize what we learn over time.

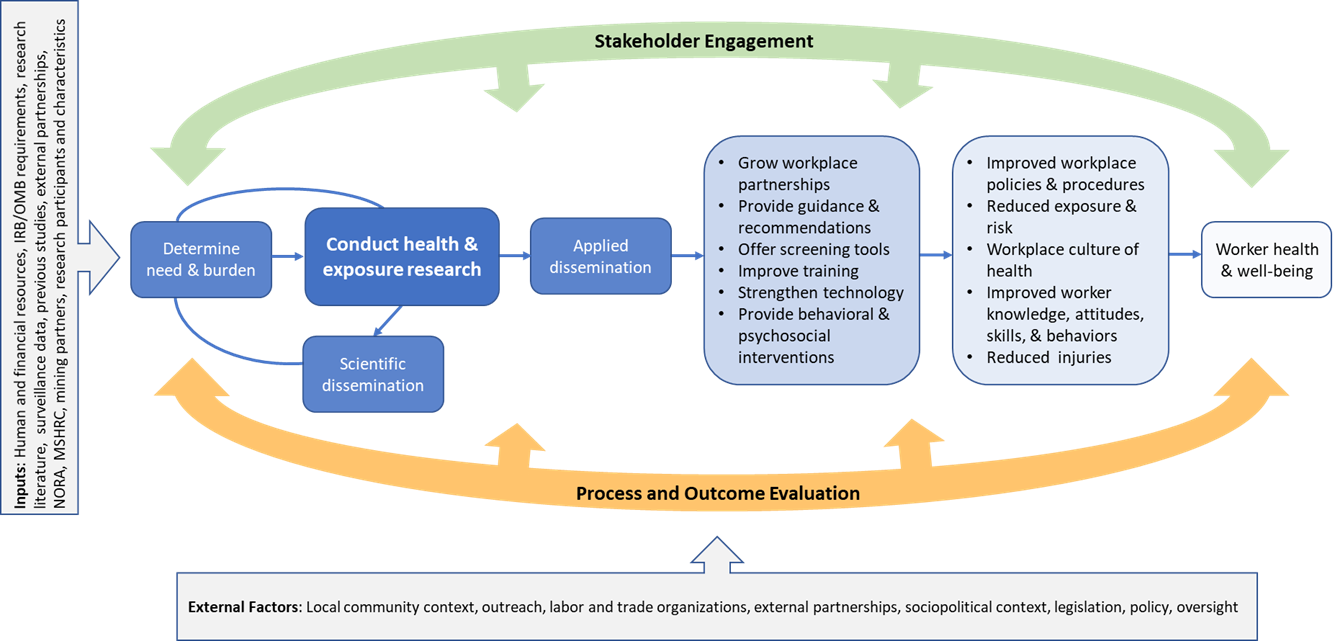

Figure 1 depicts the MHP logic model, connecting program inputs, activities, and targeted outcomes. The model illustrates how both scientific and applied workplace mechanisms are used to disseminate NIOSH research in an effort to achieve our ultimate vision of mineworker health and well-being. Scientific outputs are regularly used to increase generalized knowledge and advance the state of the science. Applied dissemination of research findings requires strategic collaboration with stakeholders to reduce hazards and promote current and future health and well-being within the context of the mining workplace. Guidance documents, training curricula, screening tools, improved technology, and behavioral interventions are examples of products that are proximal and intermediate outcomes of health and exposure research depicted in Figure 1.

The MHP logic model also highlights the importance of synthesizing surveillance data and existing research as well as engaging stakeholders in order to drive and prioritize MHP activities. Finally, the MHP logic model depicts the importance of broader contextual and external factors in influencing program outcomes and impacts. To leverage individual research projects and maximize the comprehensive value of the MHP over time, we will continually synthesize research and workplace intervention evaluation findings collaboratively with our mining stakeholders to enable a more holistic understanding of miners' health and well-being.

Burden, Need, and Impact

Burden provides evidence of the health and economic burden (or potential burden) of workplace risks and hazards. In considering these burden estimates, we also consider how well the burden evidence is assessed. Emerging issues, understudied populations, or hazards that would not have established burden due to their emerging nature would have potential burden that can be described by many of the same parameters of established burden, such as the potential for injury, illness, disability, and death.

Need helps define the knowledge gap that will be filled by the proposed research. It considers the comparative advantage NIOSH has over other research organizations and the unique resources NIOSH might have to be responsive. Analyzing need helps us to identify and address specific stakeholder concerns.

Impact considers how well our research is conceived and likely to address the need. Impact or potential for impact helps us determine whether the proposed research can create new knowledge, lead others to act on our findings, promote practical intervention, adopt a new technology, develop evidence-based guidance, aid in standard setting, or promote other intermediate outcomes. Consideration of impact allows us to analyze whether the proposed research will likely lead to a decrease in worker injury, illness, disability or death, or will enhance worker well-being.

Core Functions

Three core functions encapsulate the Miner Health Program's portfolio:

- Research

- Community engagement

- Evaluation

While each of these core functions are described separately, it is important to understand that they are not mutually exclusive. Rather, a balanced integration of all three will enhance the program's outcomes and impact.

Research

Research is at the core of NIOSH's work. As a research organization, NIOSH provides the public with objective evidence and best practices in an independent manner. Miner health and well-being research focuses on physical, biological, and psychosocial hazards and exposures; organization of work; compensation and benefits; the work environment; work-life integration; and chronic disease, among other topics. In contrast to safety-focused research aimed at mitigating the risks for acute events, injuries, and fatalities, measuring health and well-being outcomes takes longer to observe and is more complex given the multitude of intervening variables that also may influence health and well-being outcomes.

Addressing and evaluating the complex interplay between the work, health, and well-being of the mining population requires a multidisciplinary and participatory approach to ensure the integrity of the research, its application, and its ultimate utility for improving miner well-being. The program's research portfolio will build over time and reflect topics of high priority for the mining community. Priority setting within the program aims to be proactive but also flexible enough to remain responsive to emerging needs.

The MHP uses the NIOSH Burden, Need, and Impact (BNI) framework to ensure we conduct important work to protect miners and identify research priorities to guide the investment of resources in a clear and transparent manner.

Using the BNI framework, Program-led miner health research will be informed and prioritized based on the following considerations:

- A focus on mine workers who are subject to the risks and hazards of the workplace as well as those with direct influence and responsibility for ensuring miners' health and safety (i.e., all mining stakeholders);

- A clearly documented need evidenced by available data (e.g., surveillance of environmental exposures as leading indicators of health); surveillance of health outcomes and health utility (e.g., industry specific, national survey, workers' compensation claims); or prior NIOSH research indicating translational needs;

- The use of applied research methods to emphasize the application of knowledge effectively within work settings, and to have the potential to benefit worker exposure, behavior change, and interpersonal factors that facilitate or inhibit health promotion, organization of work, training, and improvement of practices and procedures;

- Issues that have greater impact on worker health in terms of frequency and severity, as well as interventions that address multiple risk factors; and

- Research that is inclusive and promotes equity to address differences in health outcomes across demographics and other key determinants of health.

Current NIOSH Mining Health Research Activities

To better inform priority areas of research, it is important to recognize research and activities across the Institute that directly and indirectly contribute to advancing the science and impact of research aimed at improving miner health.

Mining research at NIOSH is largely executed out of the Pittsburgh and Spokane Mining Research Divisions. Beyond robust injury and fatality safety solutions, current health-related research largely focuses on the control and suppression of various respirable dusts and aerosols that result from mining practices; work and organizational structures; design of equipment; prevention of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) and slips, trips and falls; limiting noise exposure and hearing impairment; and understanding and managing the effects of both heat exposures and fatigue.

The NIOSH Respiratory Health Division (RHD) has a long history of collaborating with partners to identify, evaluate, and prevent work-related respiratory diseases using multidisciplinary approaches to research. Since 1970, RHD has led the congressionally mandated Coal Workers Health Surveillance Program, which has been supplemented by the Enhanced Coal Workers Health Surveillance Program to monitor the respiratory health of coal miners in the U.S.

The Health Effects Laboratory Division (HELD) of NIOSH conducts a wide array of fundamental and applied research on workplace exposure assessment, the transmission of infectious disease, and on understanding the pathology and physiology of exposures (e.g., immunological, allergic, and inflammatory responses). Supportive health-related research has included elongate mineral particles (EMPs), diesel particulate matter (DPM), welding fumes, and respiratory crystalline silica. In addition, HELD also coordinates research and recommendations around the use of new technology in occupational safety and health through the Center for Direct Reading and Sensor Technology.

Among several areas of research that NIOSH is renowned, the National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory (NPPTL) research and certification programs directly impact miner health especially in the area of personal protective equipment (PPE) and respiratory protection. In addition, the Divisions of Safety Research (DSR), Science Integration (DSI) and Field Studies and Engineering (DFSE) are integral for maintaining advanced research practices in analytical epidemiology, field investigation methodologies, development and evaluation of protective technology, and designs of safety engineering controls and intervention. Continued coordination and collaboration with multiple NIOSH divisions will strengthen competencies needed to improve miner health and well-being.

There is also increasing recognition that factors related to both work and non-work environments contribute to worker well-being, safety, and performance in the workplace. Advancing the safety, health and well-being of workers in an integrated manner is one of the primary goals of NIOSH's Total Worker Health program. The interactions between work environment exposures and hazards with person level risk-related behavior are key focal points within TWH. There is growing evidence that integrated programs are more effective in advancing all aspects of worker health protection and promotion [Anger et al., 20158; Sorensen et al., 20139]. By enhancing worker health and productivity, the integrated research and programs that exist under TWH provide benefits to employees, employers, and their communities alike.

Community Engagement

Engaging stakeholders is predicated on the assumption that multidisciplinary collaboration enhances research and intervention [Israel et al., 200510; Stokos, 199211]. Community engagement can be defined as "the process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of those people" [CDC, 201112]. Because the incidence of illness often is influenced by social and physical environments, multiple perspectives need to be integrated to inform the research process [Hanson, 198813; Tebes, 200514]. Therefore, issues of health and well-being can be best understood and addressed by engaging with the community of interest—in this case, the mining community.

Community partners offer valuable perspectives on community life and health issues that researchers and program personnel are not able to provide. Practically, participatory research facilitates the implementation of an intervention and enhances its relevance, effectiveness, and sustainability [Israel et al., 200510; Spoth & Greenberg, 200515]. The goals of community engagement include building trust, enlisting new resources and allies, enhancing communication, and improving overall health outcomes, as described below.

- Building Trust. Community engagement efforts establish and enhance trust between community members and program administrators by acknowledging the strengths of the community, respecting cultural differences, involving the community, and utilizing transparent and collaborative methods for collecting and analyzing data, disseminating findings, and developing and implementing interventions [Sankaré et al., 201516; Shore, 200617]. This mutual trust can lead to increases in the quantity and improvements in the quality of engagement efforts [Wallerstein, 200218].

- Enlisting New Resources and Allies. Community engagement efforts enlist new resources and allies that individual parties may not possess. Community partners provide social networks and knowledge and expertise of the community, while program administrators provide scientific and research experience and often funding [Sankaré et al., 201516]. Effective engagement efforts leverage the allies and resources brought to the table by all participants [Shore, 200617].

- Creating Better Communication. As levels of community involvement increase within community engagement efforts, so too does the communication flow. Communication activities not only increase in number and frequency, but they transform from unidirectional to participatory and bidirectional [CDC, 201112]. Additionally, community engagement efforts are often able to employ formal and informal communication channels to reach community members who may not be available or accessible to outside researchers [CDC, 201112].

- Improving Overall Health Outcomes. Community engagement efforts typically employ techniques and methods that have been shown to be more effective in improving overall health outcomes. Some of these include engaging community members in the delivery of interventions; employing skill development or training strategies; involving peers, community members, or educational professionals in interventions; and developing interventions for targeted communities [O'Mara-Eves et al., 201519].

Engaging mining stakeholders in the MHP will be guided by the nine principles of community engagement described by the CDC [CDC, 201112] and listed in Table 1. The table also summarizes the MHP's completed, ongoing, and future activities related to each of the principles. The development of trust and relationships is critical to community engagement, so these activities will be given ample time within the overall timeframe of the program.

| Principles | Done | Doing | To Do |

|---|---|---|---|

| Be clear about the population/goals to be engaged and the goals of the effort | Clearly defined "mining community" and all subgroups; established NIOSH-funded intramural research projects | Developing the Miner Health Program Strategic Plan; MSHRAC workshop | Regularly evaluate what groups comprise the "mining community" and conduct outreach to ensure relevance and equity |

| Know the community, including its norms, history, and experience with engagement efforts | Established broad definition of "stakeholders" within the NIOSH Mining Program | Analyzing available health data to identify health issues | Conduct formative research about the community’s norms, history, communication preferences, needs; conduct research to identify the health concerns of the community |

| Build trust and relationships and get commitments from formal and informal leadership | Formed MSHRAC Health workgroup; identified NIOSH Project Leader | Building relationships across NIOSH to coordinate and communicate Institute-wide activities related to miner health research | Identify/designate “leaders” or points of contacts for each community group; identify/designate NIOSH liaison to community |

| Collective self-determination is the responsibility and right of all community members | Sought input from MSHRAC workshop on development of Strategic Agenda | Seek and incorporate input from community into strategic and research plans | |

| Partnering with the community is necessary to create change and improve health | Establish community partners and collaborate with them to collect data, confirm findings, develop and evaluate interventions/messages; establish mechanisms for sharing information and communicating | ||

| Recognize and respect community cultures and other factors affecting diversity in designing and implementing approaches | Develop and disseminate culturally appropriate and useful products, tools, and messages that are tailored to meet the community’s needs | ||

| Sustainability results from mobilizing community assets and developing capacities and resources | Expanding NIOSH Miner Health Program personnel; identifying resources available through MSHRAC | Develop communication capabilities/resources/personnel; identify and utilize assets and resources available through the mining community | |

| Be prepared to release control to the community and be flexible enough to meet its changing needs | Develop data collection instruments that the community can implement independently; develop a communication mechanism that allows easy communication between MHP and the mining community | ||

| Community collaboration requires long-term commitment | NIOSH funded intramural research projects for 1–5 years | Establish collaborations, partnerships, and MOUs with stakeholder groups |

Stakeholders are the end users of our research and therefore our research is largely driven by their needs. Our stakeholders are diverse, and each group has unique perspectives and interests related to worker health and well-being. Consistent with prior NIOSH practices, the MHP will continue to convene multi-stakeholder partnerships to bring diverse perspectives to the table. This model for collaboration has proven to be highly effective. In September 2019, a Miner Health Workshop was facilitated by a working group within the Mine Safety and Health Research Advisory Committee (MSHRAC). This workshop aimed to attract a broad base of NIOSH Mining stakeholders, including individuals from academia, government, the mining industry, trade associations, organized labor, regulatory agencies, research laboratories, and suppliers. In the spirit of community engagement, this collaboration was a first step toward informing research priority areas for the Miner Health Program. We will continue to build in meaningful engagement mechanisms to interact with our stakeholders, not only for priority setting but throughout the research and translation processes. Ultimately, stakeholders must be engaged for our workplace products and interventions to be both effective and utilized.

Evaluation

Evaluation serves as a primary component of the MHP. Although evaluation is a vital component of scientific research and research programs, it is often overlooked. In broad terms, program evaluation is used to answer three types of questions:

(1) Was the program implemented as intended?

(2) What outcomes are associated with program participation?

(3) How can the program be improved?

While oversimplified, these questions illustrate the complementary purposes of process evaluation, outcome evaluation, and quality improvement, respectively.

Process evaluation is used to assess the extent to which research or intervention activities are implemented as planned. Process evaluation also assesses the extent to which the program or intervention is reaching the intended target population and may explore reasons for attrition. When completed proactively, evaluation findings can be used to adjust implementation to more accurately meet expectations or can address flaws or challenges in the initial implementation plan.

Outcome evaluation is used to determine the effectiveness of a program by measuring the extent to which program activities are associated with knowledge, attitudes, skills, behaviors, and organizational factors that ultimately promote health and well-being among mine workers. Outcome evaluation findings most often are used to justify continued investment, argue for program expansion, compare the effectiveness of alternative interventions, support quality improvement, formulate policy, and serve as a tool for program accountability to stakeholders. Although outcome evaluation is intended to answer the question, "Does the program work," other key questions include "Does the program work equally well for all participants?" and "Does the program work in all circumstances or settings?" These other key questions concern the generalizability of program effects across subpopulations of workers as well as settings. These are important to ask to ensure equity across demographic characteristics such as age, race, ethnicity, and sex, and similarly, if program effects vary across geography, mine type, or organizational characteristics.

Program Goals and Objectives

For each of the three core functions (Research, Community Engagement, and Evaluation), specific objectives and goals have been established to address fundamental and emerging needs for characterizing work-related exposure and illness and optimizing mine worker health. While each objective takes into consideration current organizational capacity and development needs, their selection also incorporates direct communication and feedback from stakeholders in the two years leading up to release of this plan.

Prior to the 2019 MSHRAC workshop, health- and exposure-related topics of importance were identified by several mining industry, trade, union, and academic stakeholder groups during a half-day meeting facilitated by the National Academy of Sciences. To aid the foundation of this Agenda, the MSHRAC subcommittee summarized information from both settings in a report provided to NIOSH that presented current research gaps, mechanisms to improve communication and participation in occupational health research, and methods that would help measure or demonstrate progress in improved mine worker health and well-being.

The workshop summary report identified research gaps related to (in no particular order) behavioral health and substance use/misuse, heat exposure, fitness for duty, exposure to dusts and aerosols (e.g., silica, DPM, welding fumes), and the reliable surveillance of acute and chronic health outcomes (e.g., silicosis, heat stress). It is important to note that the foundational research of the MHP is supported by current studies in heat stress, fatigue, and the evaluation and analysis of survey data sources; however, these projects are in-process and results have not yet been finalized and communicated. In terms of evaluation, stakeholders agreed that the effectiveness of the Miner Health Program should be measured by the partnerships it develops (i.e., formal and informal engagement in research, communication, and evaluation), and by using surveys and health outcome measures, when available and appropriate. Ideas for improving community engagement were for NIOSH to seek additional opportunities for collaboration, and to generate and share best practices with community partners using exemplar case studies whenever possible.

For the purposes of this Agenda, strategic objectives represent changes at the social system-level. In turn, each objective is supported by intermediary goals and associated activities. Successful accomplishment of these goals will be dependent upon a transdisciplinary approach with stakeholders from many diverse groups, including workers, employers, labor organizations, health promotion and wellness professionals, occupational safety and health practitioners, policymakers, academic and government researchers, and others.

Strategic Objective 1 - Research:

Conduct etiologic, surveillance, exposure, and intervention research that advances protection from work-related health hazards and addresses the overall well-being of mine workers.

To better understand the health experience of miners and to investigate factors that influence worker well-being, we will:

- establish a framework to systematically measure and compare outcomes, conditions and exposures over time as well as relative to other occupational groups (on an ongoing basis and in perpetuity);

- conduct studies on conditions that affect readiness-for-work (e.g., heat exposure, fatigue, mental health, substance use/misuse, musculoskeletal disorders);

- complete studies to better understand patterns of aerosols exposures (e.g., silica, coal dust, diesel particulate matter) and associated health status across mine sectors and among active and retired mine workers;

- complete studies to understand organizational commitment to safety, health, and well-being, and the impact on worker health (e.g., risk assessment and implementation strategies); and

- identify work practices, programs, and interventions that promote and demonstrate worker health and well-being.

To address new and emerging health hazards and sentinel events, we will:

- conduct analyses and assessments to better understand the distribution and determinants of acute or previously unknown adverse health risks;

- collaborate with our community partners to identify and address health behaviors that impact the health of mine workers; and

- propose recommendations and best practices for maintaining a healthy work environment.

Strategic Objective 2 - Community Engagement:

Work collaboratively with mining stakeholders to address issues affecting the well-being of miners by building trust, enlisting new resources and partners, and improving communication to promote the exchange of ideas and best practices.

To achieve this objective, we plan to:

- develop partnerships and collaborations with community stakeholders, establish mechanisms for information exchange about present needs and research, and promote opportunities for engagement in research and evaluation activities;

- build strategic expertise in health communications to improve communication with stakeholders;

- coordinate and collaborate with NIOSH programs and researchers to leverage health research relevant to miner health outside the Mining Program; and

- cultivate trust with our mining stakeholders by engaging in joint efforts and collaboration to integrate occupational health activities with workplace practices and programs.

Strategic Objective 3 - Evaluation:

Build capacity to prospectively evaluate and communicate the efficacy and effectiveness of Miner Health Program research, outputs, and workplace interventions in order to support continuous improvement and improved health of the mining workforce.

To achieve this objective, we plan to:

- build the MHP's evaluation readiness and capacity;

- engage stakeholders in the design and conduct of evaluations, as well in the use of evaluation findings for improvement;

- develop a systematic approach to assess if program activities are carried out as planned to enable continuous quality improvement; and

- document short to longer-term outcomes associated with the MHP.

Sustainability

To be successful, the Miner Health Program cannot be solely dependent on any singular function, individual, or group. As a collaborative effort, long-term commitments and engagement with the mining and research communities will be integral to progressing toward the shared vision of improved well-being for the entire mining population. As indicated by the nine principles of community engagement, sustainability will be achieved by mobilizing community assets, developing capacities and resources, and enabling the community, as needed. As such, we will foster leadership within the MHP from both our internal and external stakeholder groups. While the initiation and organization of the MHP will be led by NIOSH, the Program’s ultimate sustainability will be dependent on identifying and enabling multiple leaders from each community group, across functions, to fully engage and inform the work we do.

Notice

- DOL [1974]. Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970. Public Law 91-596, 84 STAT. 1590, 91st Congress, S.2193, December 29, 1970. United States Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration

- Buttorff C, Ruder T, Bauman M [2017]. Multiple chronic conditions in the United StatesPDF. RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA.

- Schulz A, Northridge ME. Social determinants of health: implications for environmental health promotion. Health Educ Behav. 2004 Aug;31(4):455-71. doi: 10.1177/1090198104265598. PMID: 15296629.

- Ahonen EQ, Fujishiro K, Cunningham T, Flynn M. Work as an Inclusive Part of Population Health Inequities Research and Prevention. Am J Public Health. 2018 Mar;108(3):306-311. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304214. Epub 2018 Jan 18. PMID: 29345994; PMCID: PMC5803801.

- Hege A, Lemke MK, Apostolopoulos Y, Sönmez S. Occupational health disparities among U.S. long-haul truck drivers: the influence of work organization and sleep on cardiovascular and metabolic disease risk. PLoS One. 2018 Nov 15;13(11):e0207322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207322. PMID: 30439996; PMCID: PMC6237367.

- Lingard, H., & Turner, M. (2017). Promoting construction workers' health: a multi-level system perspective. Construction Management and Economics, 35, 239 - 253.

- Chari R, Chang C, Sauter SL, Petrun Sayers EL, Cerully JL, Schulte P, Schill AL, Uscher-Pines, Lori [2018]. Expanding the paradigm of occupational safety and health: A new framework for worker well-being. J Occup Environ Med 60(7): 589–593.

- Anger WK, Elliot DL, Bodner T, Olson R, Rohlman, DS, Truxillo, DM, ... & Montgomery, D [2015]. Effectiveness of total worker health interventions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(2): 226.

- Sorensen G, McLellan D, Dennerlein JT, Pronk NP, Allen JD, Boden LI, ... & Wagner GR ([2013]. Integration of health protection and health promotion: rationale, indicators, and metrics. Journal of occupational and environmental medicine/American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 55(12 0): S12.

- Israel, BA, Parker, EA, Rowe, Z, Salvatore, A, Minkler, M, Lopez, J, . . . Halstead, S. [2005]. Community-based participatory research: Lessons learned from the Centers for Children's Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environmental Health Perspective, 113(10): 1463-1471.

- Stokols D [1992]. Establishing and maintaining healthy environments: Toward a social ecology of health promotion. American Psychologist, 47: 6-22.

- CDC [2011]. Principles of community engagement (second edition)PDF. Atlanta: CDC/ASTDR Committee on Community Engagement. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NIH Publication No. 11-7782.

- Hanson P [1988]. Citizen involvement in community health promotion: a role application of CDC's PATCH model. Int Quar Comm Health Ed 9(3):177–186.

- Tebes JK [2005]. Community science, philosophy of science, and the practice of research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35(4/5): 213-230.

- Spoth RL, & Greenberg MT [2005]. Toward a comprehensive strategy for effective practitioner-scientist partnerships and larger-scale community health and well-being. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35(3/4): 107-126.

- Sankaré I, Bross R, Brown A, del Pino H, Jones L, Morris D, Porter C, Lucas-Wright A, Vargas R, Forge N, Norris K, Kahn K [2015]. Strategies to build trust and recruit African American and Latino community residents for health research: A cohort study. Clinical and Translational Science 8(5):412–420.

- Shore N [2006]. Re-conceptualizing the Belmont Report: a community-based participatory research perspective. J Comm Practice 14(4):5–26.

- Wallerstein N [2002]. Empowerment to reduce health disparities. Scandinavian J Pub Health Suppl 59:72–77.

- O'Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, Oliver S, Kavanagh J, Jamal F, Thomas J [2015]. The effectiveness of community engagement in public health interventions for disadvantaged groups: A meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 15(129).

- Institute of Medicine [2002]. The future of the public's health in the 21st century. Washington: The National Academies Press.

- WHO [2006]. Constitution of the World Health Organization—basic documents, forty-fifth edition, supplement, October 2006PDF. World Health Organization.

- Total Worker Health® is a registered trademark of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).