The David J. Sencer CDC Museum will re-open with new visitation protocols on January 2nd, 2026. All visitors must make advanced reservations. Walk-in visits are no longer permitted.

The following information is required while making reservations:

- Visitors to provide first, middle, and last name

Visitors 18 and over will also need to submit:

- Date of birth

- Citizenship (Select U.S. or non-U.S. citizen)

- Government-issued valid (not expired) REAL ID number or passport number

Bring confirmation email(s) for museum visit.

EIS Class Gifts

The tradition of class gifts, also known as class plaques, was initiated in 1953, when the inaugural class of ’51 presented the Director of Epidemiology, Alexander D. Langmuir, two well worn leather shoes that had come to symbolize the shoe-leather epidemiology practiced by Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) Officers. Alex put the plaque on the wall in his office and a tradition was begun. Each subsequent class presented Alex a plaque that symbolized its 2-year experience and he put them on the wall for everyone to see. The presentation was made at another traditional activity, the EIS Skit, performed for Alex, staff in the Epidemiology Branch, as well as current and incoming EIS Officers. So each class was challenged early to produce a funnier skit (some years more successful than others) and better plaques.

Over the years, the organizational home for epidemiology changed, with new names as CDC grew, but EIS and its traditions remained. There has been a skit each year to the present, except in 1955 when the EIS conference was cancelled so that an investigation of contaminated polio vaccine could be conducted. Later known as the Cutter incident, this investigation put CDC and EIS in the national spotlight for the first time.

The gifts, on the other hand, did not share a similar fate. In the 1980s, the Director ran out of wall space, and the gifts were housed in Philip Brachman’s attic. Starting in 1989, when for several months there was no permanent Director of Epidemiology, the gifts were not presented. In 2003, the class of 2001 renewed the tradition, however, and gave its plaque to the EIS Chief. In 2004, the gifts were donated to the CDC David J. Sencer Museum (formally known as Global Health Odyssey Museum), located at CDC Headquarters.

The EIS Class Gift exhibit provides pictures and background stories from the donor class. The gifts and stories provide something of the lighter side of the EIS experience, an experience that benefits from humor and bonds these officers not only within each class but across decades.

The exhibit will continue to grow as we learn more about the history of each EIS class. Graduates who wish to update, correct, or supplement this site are asked to please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov.

74 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

75 officers

The project was spearheaded by Jennita Reefhuis and Jenny Williams, and was constructed over a 3-month period in Jenny Williams’ dining room.

The red-white and blue colors in the gift were for the colors of our flag. The events of 2001 had such a profound impact on us as a class and as a nation, and we felt that representation was really appropriate. We wanted to have a project reminiscent of the old quilting bees, where folks sat around and visited while throwing in a stitch or two. Since so many of us traveled and had unpredictable schedules, we wanted a project everyone could contribute to as their time allowed. We had set days to meet at my house to work on the quilt. The design for the blocks was patterned after crazy quilts, where you take scraps of fabric sewn together at different angles. We would take these large swatches of assembled pieces, and then cut blocks to size. This pattern allowed the “non-sewers” in the group to get behind a sewing machine and drive some…without having to worry so much about being precise with the block. We used footprints for the border to symbolize “shoe-leather epi.” Each block is signed by a 2001 EIS officer.

A quilt frame was made by one of the EIS officer’s father, so more than one person could work on it at a time. The quilt was placed on the frame, and we had quilting evenings. Anywhere from three to eight officers would show up any given night to throw in some stitches. (A few spouses, friends, and kids help too.) Most of the class worked on the quilt, even for just a small part.

Lisa Pealer (EIS’ 01) took the leftover swatches from our blocks, and had her mom (who is a wonderful seamstress) make a vest for Doug Hamilton (EIS chief). We are sure he wears it with pride during 4th of July parades, or when he is doing his Uncle Sam impersonations.

Submitted by Jenny Williams and Jennita Reefhuis (EIS ’01)

88 officers

I remember volunteering to organize the class gift because I didn’t want to be in charge of the class skit. Some of us tossed around ideas. Mine was the idea of the photo montage in the shape of the emblem of shoe leather epi work. I’d seen similar posters of a large picture/scene composed of many small photos. Crazy me, I thought I could probably put one together for us. Others liked the idea and so it began. Over the months (yes, months) leading up to the April conference, I requested, cajoled, and harangued everyone in our class for a photo of themselves. The request I made was that they try to contribute a picture in which they were engaged in epi – whether field work, in the office, or whatever. We’d (a group of us that would keep an ongoing email conversation about this) decided that we wanted to include the EPO staff who meant so much to us as they’d supported us through our EIS joys, trials, and tribulations. When the time came, we took pictures of them against a blank white wall (I’m sure they were wondering in what nefarious way we might use the photos, and I cropped them to place in the “hole” of the shoe. Once the complete picture was done, I think it was Victoria who got it printed and framed, and then during EIS week, we passed instructions around to everyone on where we’d hidden it, so that they could sign it.

Submitted by Sarah Y. Park (EIS ‘02)

79 officers

The gift of the two photographs was inspired by our time at the USPHS Training Center in Anniston, AL where we did a course in biohazards and emergency preparedness. It included training in using biohazard materials and dealing with potential bioterrorism scenes (hence the photo in full biohazard gear). As the Class of 2003, we were the second class selected after 9/11/2001 and the anthrax attacks. Our curriculum was the first to reflect the changing priorities and concerns after those events. The course in Anniston provided critical training that was useful not just for managing bioterrorism, but also for managing other types of outbreaks, such as pandemic influenza, which since then has become a focus of public health response. Anniston also meant that we were the first class to be taken to a completely off-site location as a group. For a week, we were a captive audience in a small town in a small hotel, and the class really bonded. We BBQ’d in the back of the hotel, had chicken fights in the pool, and really got to know each other. Doug Hamilton often commented on how close our class was during our two years at CDC, and how close we have stayed over the years. The two photos captured us as a normal EIS class and us clowning a little, but also at the turning point for EIS officers and public health professionals, as the new realities of the post-9/11 era started to change our training.

The class conceived of the gift together, and virtually everyone signed. It was easy to do that because we were so close and connected. We even had our own listserv.

Submitted by Amy Dubois (EIS ’03)

90 officers

The class gift to Doug Hamilton and Lisa Pealer (at the time) was threefold. We gave them gift certificates, a large appreciation poster (signed by the entire class) with a picture of a hand holding an academy award) as well as their own “Oscar.”

The whole skit had an academy award theme to it (complete with a red carpet entrance and our own Joan Rivers and the whole “who are you wearing”) and the skits were presentations of oscar-like awards, only the statuettes were little golden people. Please keep in mind that this was done in no disrespect to our former director – the statuettes were handmade miniature versions of Dr. Gerberding, in the famous red dress. We called those “Gerbies” and they were made out of Barbie type Dolls and then painted, and dressed to look like our former director.

Ezra J. Barzilay (EIS ’04)

79 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

82 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

79 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

80 officers

The EIS class gift of 2008 was a Commissioned Corps sword given to CAPT Doug Hamilton and the EIS staff for their exceptional leadership. The sword was chosen because it came up in discussion often throughout our two years, and while the item has a history in tradition, it also has the “coolness factor” which exemplifies many of our experiences during EIS. The evening Doug was presented with the gift he was called onto the stage and “knighted” by Elissa Meites, a representative for our class. It was a very touching moment for all involved, in which he was equally surprised at the gift and, let’s admit, pretty impressed — it is a sword after all.

As many of us were honored to work in Haiti after the devastating earthquake of January 12, 2010, the class of 2008 also made a contribution to Partners in Health in honor of the EIS program. This organization was chosen because of its excellent reputation and effectiveness in providing medical care and assistance to underserved populations in many areas of the world, including in Haiti.

We enjoyed each and every day as EIS officers. We learned so much during EIS about epidemiology (gumshoe epi), politics, life, friendship, travel and so much more! We wanted a way to share our thoughts and thank the EIS program. We figured that the best way to do that was to write our thoughts on a card shaped like a shoe, the symbol of EIS! We hoped this card might eventually hang in the CDC museum alongside the artwork of our predecessors.

Our skit night also featured a flight safety video with participation from CDC director Tom Frieden. In keeping with this theme, all the members of our class (as well as other skit guest stars, including H1N1 flu leaders Lyn Finelli and Dave Swerdlow) received a gold flight wing pin engraved with the words “EIS Class of 2008.” These thoughtful details may have been what prompted Doug to call our skit “the best of any of the skits that I’ve seen at CDC.” And we have that in writing.

Submitted by Deborah Christensen, Danielle Iuliano, Matt Gladden, Elissa Meites, Roodly Archer and Carrie Nielsen (EIS ’08)

82 officers

In the fall of 2010, a state-based officer asked everyone in the class complete the sentence “When I started EIS, I never thought I would…” She needed this information for a presentation at a hospital where she hoped to get a job. Dozens of people sent in responses which were representative of our class’s experience. The entire class was asked to send in material for use in the project, and over half sent in anecdotes or photos.

Submitted by Lee Hampton (EIS ’09)

61 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

77 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

80 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

67 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

64 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

75 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

68 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

69 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

75 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

71 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

51 officers

The prevailing concern during 1980-1982 was the federal budget cuts in the first years of Ronald Reagan’s presidency. At the same time, CDC reorganized in 1981 from the one Center for Disease Control to the Centers (plural) for Disease Control, creating new centers that all competed for the limited funds that were available. Budget cuts were not limited to CDC – almost every health, social, and informational agency was targeted. The Reagan administration closed the U.S. Public Health Services hospitals, creating a reduction in strength of the Commissioned Corps (with more senior officers bumping more junior officers), and the Commissioned Corps itself was almost abolished. So our class was very concerned about funding of the agency itself and whether CDC would be able to hire any of us post-EIS. CDC’s in-house cartoonist Ed Biel was the artist.

The poster may not have been a class decision (or perhaps we all said, “Yeah, sure, fine” to someone’s suggestion), but I don’t know who brought the idea to Ed Biel and asked him to sketch it with our caricatures.

Submitted by Richard Dicker (EIS ’80)

I think credit for the “Budget Wars” theme is primarily deserved by Ronald Reagan and his budget director, David Stockman, for having proposed severe Reductions In Force (RIFs) to PHS, among other hits to public health in the early 1980s, that actually succeeded. (Obviously, the EIS was saved).

Submitted by Bruce Weniger (EIS ’80)

65 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

49 officers

We started EIS in July, 1982. Reagan had been in office for just over a year when we started. Even though the AIDS epidemic was unfolding during EIS, Reagan was virtually silent about it.

For a while the American government completely ignored the emerging AIDS epidemic. In a press briefing at the White House in 1982, a journalist asked a spokesperson for President Reagan “…does the President have any reaction to the announcement – the Center for Disease Control in Atlanta, that AIDS is now an epidemic and have over 600 cases?” The spokesperson responded – “What’s AIDS?” To a question about whether the President, or anybody in the White House knew about the epidemic, the spokesperson replied, “I don’t think so.”

It was not until more than a year after our EIS class graduated (17th September 1985), that President Reagan publicly mentioned AIDS for the first time, when he was asked about AIDS funding at a press conference. Critics were quick to ask why, if AIDS had been a ‘top priority’ among the government, the president had not mentioned it in public before.

In fact, on April 23rd, 1984, Margaret Heckler reported that the AIDS virus had been found, but controversy surrounded who actually made the discovery. A few other political issues also come to mind. Reagan appointed Koop as Surgeon General in early 1982, just as we started EIS. Much of his work was political (e.g., tobacco, AIDs, abortion). Also, Bill Foege (a CDC legend) was replaced by Jim Mason about half-way through our EIS. That may have been viewed as a political change of the guard, from the old CDC shoe-leather epi, to a Republican appointee from Utah (although in the end, Jim Mason’s tenure was quite distinguished).

Submitted by Patrick Remington (EIS ’82)

71 officers

The MMWR portrayed with our class picture represents a satirical publication consisting of a one sentence update of smallpox surveillance in week number 4,652 following it being declared eradicated. The report shows no cases, and the list of contributors consists of all the members of our EIS class. This was a spoof on CDC “resting on its laurels” by mentioning the one successful disease eradication campaign at every opportunity presented.

The caption in Latin means: “A biennium (2 years) with Carl, a lifetime with Hygeia.”

The skit was by Mark Eberhart and Ann Hardy. She and I worked in what was then CDC’s “AIDS Activity.”

Submitted by Ken Castro (EIS ’83)

Ken — I agree with your recollection of the MMWR. In addition, I think the article served as a comment on the MMWR’s tendency at the time to list large numbers of “contributors” — seemingly defined more by geographical proximity to the events described rather than any effort they had put into the article, and, of course, except the EIS officer who actually wrote it.

Now, I may be making the following up, but I have a vague recollection of someone (maybe Mary Moreman) coming to us around or even after the time of the skit itself and asking “what about the gift?” I’m also thinking she got blank stares from us.

But, and this may be total confabulation, I’m thinking one of the skits was a musical number about an EIS officer seeking the path to glory investigating an outbreak of chronic diarrhea (the punch line was his Langmuir paper finding a highly significant association between chronic diarrhea and toilet use). A prop in the skit was a giant Q-tip-like swab he carried around swabbing everything. At one point the plan was to retrofit that as the “gift” (with all that it connoted) but I don’t remember if that actually happened.

Submitted by David Fleming (EIS ’83)

The Q-tip belonged to Mark Eberhardt’s and Ann Hardy’s act…. Stuart and I had this humongously large agar plate that I licked, while Stuart did a roll up and down the key board at the halfway point in the song. Parts I’ve forgotten, although Rob Tauxe immortalized it on a CD that I have somewhere, and I still sing it softly to myself before viewing any Tuesday morning seminar….here’s what I remember:

“I’m afraid Valdosta’s made of Sweet Georgia Brown,

If you took what’s not been cooked, you got Sweet Georgia Brown,

They all cry and wanna die when they get Sweet Georgia Brown,

I’ll tell you just why,

y abstract don’t lie, (not much)

If you took what’s not been cooked, you got Sweet Georgia Brown,

It’s a shame, but what’s to blame for Sweet Georgia Brown?

The chicken, ice cream, or just the town?

Can you tell me where the agent’s gone?

And can you tell me, now, where’s the john?

Georgia claimed it, and I named it

Sweet Georgia Brown”

Submitted by Terry Chorba (EIS ’83)

As I recall it through the dim mists of fading memory, Ken and Dave are correct. One day, after the EIS skits were over, I think, somebody came to us and said, “What about the class gift?” Dave is no doubt correct; it was probably Mary Moreman. Carl Tyler mentioned to somebody the lack of a gift from our class and was not pleased about the omission.

I created the framed presentation. I remember laying out the poster on the dining room table at Dan Fishbein’s house (EIS ’83), where I was living, and rubber gluing all the photographs. I think it was my idea to add the Latin phrase, “Biennium cum Carl, Vita cum Hygeia.” I called a Latin professor at Emory to make sure I got it right. Ken is correct on the English translation. I think a few of us went to Carl’s office and presented it to him. We were forgiven.

The fake MMWR on smallpox was the cover of the program at the annual EIS skits for our class year. I think Suzanne Smith (EIS ‘83) had a hand in creating it. The list of names appears to be a real list of all the people who did work on smallpox eradication.

Submitted by Fred Shaw (EIS ’83)

61 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

69 officers

My memory is that the lightning bolt was related to the following: During our EIS Summer Course field exercise, we conducted a telephone survey which led to observation/testing of fire detectors in homes. During the one evening when we were scheduled to conduct the telephone survey, we were in offices spread throughout Building 1 at Clifton Road. Our phone survey was in progress when a severe thunderstorm with lightning occurred, and the electricity in Building 1 went out. However, to keep to our tight timeline, we had no choice but to forge ahead, so we conducted the telephone survey basically in the dark using flashlights, etc. The publishing of this study was coordinated by Jim Mendlein from our class and was published in the MMWR during the time that Mike Gregg was Editor (Prevalence of smoke detectors in private residences–DeKalb Country, Georgia, 1985. CDC, MMWR 1986;35:445-448). Our class T-shirt that we all wore on skit night at our EIS “graduation” was red and also had a black lightning bolt on it.

Finally, my memory is that Carl’s cowboy motif is related to Carl’s “sabbatical” at the Oklahoma State Health Department during our EIS tenure. My understanding is that as Director of the EIS Program, Carl wanted to stay in touch with EISO issues, as well as federal/state relation issues by spending some time in a field location which had a current EISO.

Submitted by Polly Marchbanks (EIS ’85)

The use of a PC as iconic of the EIS 85 experience is because we beta tested the very first (MS- DOS) version of Epi Info. We analyzed data from our field project in the small amphitheater of the main building at Clifton Rd (now the Roybal campus). Epi Info was installed in several PCs (with 5 ¼ floppy disks and “luggable” Compaqs with “huge” 20MB hard disk drives!).

Submitted by Jose Becerra (EIS ’85)

51 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

64 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

68 officers

The collage uses EIS photos of all of the people in our class. The photos on the ship are of the staff whose assignments were in Atlanta; on the dingy were the folks in field positions; and on the life preserver were the two who had DC area assignments.

The inspiration was based on the theme for the class skit, which was called the “HHS Pinafore.”

Submitted by Christine Branche (EIS ’88)

There were several cruise ship outbreaks that EIS members of the class of 1988 contributed to investigating, and so the cruise ship montage was a convenient way to get the photos of each member displayed in the class gift. I don’t remember any particular outbreak that was exceptionally large or newsworthy, but the graphics people at CDC helped put the montage together for us.

Submitted by Anne Schuchat (EIS ’88)

67 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

51 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

44 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

51 officers

The EIS Class of 1972 gift is in the tradition of many prior classes. When Philip S. Brachman, M.D. (EIS 1954), took over as Director of the Epidemiology Program at the Center for Disease Control, he inherited Dr. Langmuir’s corner office at 1600 Clifton Road, including an already well-developed frieze of whimsical placards, each bearing the signatures of an outgoing class in the context of some memorable aspect of its two- year tour of duty. Over the years the placards grew perhaps in drollery but definitely in size, presumably compelling eventual termination of the tradition in the interest of preserving some recognition of the original functional demands of the space.

Obviously a parody of the national coat of arms from the obverse of the Great Seal of the United States, the Class of 1972 placard celebrates the bureaucratic upgrading inherent in the passage from the Epidemiology Program to the Bureau of Epidemiology. At the center, “EIS” is inscribed on the chief of the shield, and the paleways of 13 pieces from the original blazon are transmuted into a frequency histogram—a classic epidemic curve with descending limb. The bald eagle supporting the seal clutches a vaccine-filled syringe with bared needle in place of an olive branch and three culture swabs instead of 13 arrows. The ribbon in the eagle’s beak substitutes “IN PHIL [Brachman] WE TRUST” for “E PLURIBUS UNUM.” Over the eagle’s head Dr. Brachman’s visage looks out from a glory of 19 cotton balls (from an era before individually packaged isopropyl alcohol pads). Adumbrations without allusion to the original include the motto, “Quick and Dirty”—the rapid analysis of immediately available data to provide initial direction to the outbreak investigation. There is also a ring of worn soles from shoe-leather epidemiologists. At twelve o’clock, “FBE” supposes a Federal Bureau of Epidemiology in parallel with the FBI. The 52 encircling soles bear the signatures of the 51 men in the Class of 1972 plus, just clockwise to “The Class of 1972” at six o’clock, that of Deborah L. Jones, whose tenure at the MMWR had begun as the Class of 1972 was assembling in Atlanta, and who two years later shone in the center of the “My Favorite Things” MMWR skit as the only woman in the April Satirical Review, which concluded with the presentation of the placard to Dr. Brachman.

Submitted by William Baine (EIS ’72)

42 officers

The inspiration for this gift comes from the strict emphasis placed on completing a well-supported, well- written Epi-2 within the required tight time frame. The “silver-bullet suppository” was available to provide assistance. Our class responded to a large number of Epi- Aid Requests.

It appears to be a rectal suppository to facilitate anal- compulsive EIS officers to write better Epi-Aid reports or Epi-2s.*

Submitted by Jeffrey P. Davis (EIS ‘73)

*Submitted by Barry Levy (EIS ’73)

45 officers

The EIS Class of 1974 gift is one of the “classics.” Since 1976 was the 25th anniversary of the EIS, silver was chosen. The group developed an award, called the “Silver Alex” in honor of Alex Langmuir, who founded the EIS. We got a collection of shoes, made sure each one had the trademark “shoe leather hole” on the sole, and painted them silver. Because it was presented at the 25th anniversary of the EIS, “Silver Alex’s” were awarded to key mentors who harassed us during our two years, similar to the Oscar Awards Ceremony. In between the acts of our skit, we called the winners of the Silver Alex’s up to the stage to receive their awards and make victory speeches. It’s not clear how much our CDC mentors appreciated their Silver Alex’s, but it was all in good fun. The best retort by a Silver Alex winner came from Carl Tyler, who teased “if only the members of the Class of ’74 had been as creative in their EIS lives as they were in the skit, they would have many more epi products to show for it.” Ward Cates was the Director of our skit and Walter Orenstein played the role of Phil Brachman, then the Chief of the EIS. We remember the Bill Foege impersonator in the skit was an angel (Peter Schantz) since Bill was considered so flawless.

The Class of 1974 gift in the picture was a plaque with the prototypic Silver Alex surrounded by the signed pictures of all 45 classmates– we were quite a rowdy bunch!

Submitted by Ward Cates and Walt Orenstein (EIS ’74)

52 officers

First international officer

The 1975 Class Gift “Phillie’s Angels” was a “triple- play” pun. The first pun referred to the American Legionnaires investigation of a number of Legionnaires who became ill in Philadelphia shortly after the bicentennial in July 1976. The Legionnaires outbreak was a big deal for our class. Many CDC staff were deployed to Philly and neighboring areas and States to work on the outbreak, including many regional EIS field officers and a number of Atlanta- based officers. There were many theories for the severe respiratory illness of Legionnaires’ Disease. Legionellosis was ultimately proved to be caused by the newly discovered Legionella pneumophila organism after CDC was finally able to culture the etiologic agent.

The “Phillie’s Angels Team” (note the apostrophe denoting the possessive case) also referred to Phil Brachman, the head of the EIS program during our time. The EIS Class of 1975 was his “team” of angels flying in to assist in outbreak investigations, and we were acknowledging him. The third part of the pun referenced a popular TV series, “Charlie’s Angels” whose angels were sent in to troubleshoot, too, only with more stylish outfits than EIS officers.

The broken bat and baseball team motif (arguably a fourth pun swinging for a bases-loaded home run) may have referenced intramural sports competition between the traditional Atlanta- based officers and the field officers of the EIS program. We were great friends, but we were a competitive bunch….

Submitted by Dick Jackson, James Stratton, Steve Englender, and Mark Oberle (EIS ’75)

39 officers

This plaque continued a tradition that each class presented the Epidemiology Director a humorous gift that could be displayed in his office. It was presented to Dr. Brachman on skit night during the EIS conference. Henry Retailliau constructed the gift at his home. Individual photos of all the class appear on the gift.

Dr. Brachman and Virgil Peavy were very visible in the summer course and throughout the two years. They, in particular, told us on a regular basis how we would lose the softball game (as had every class in prior years). Instead we won rather handily, and we took the opportunity to remind them of their humiliation. The oil derrick alluded to the Kuwait training course conducted by Philip and Virgil while we were officers.

Dr. Brachman was also given a necklace made of Watney’s Ale mini barrels from the John Snow pub in London, recognition of our appreciation of the field of epidemiology.

Submitted by Stephen Thacker (EIS ’76)

43 officers

The T-shirt was made for Phillip Brachman, who was director of the EIS at the time and it was for the EIS Conference Fun Run. I believe we all contributed to the idea, as we all signed it.

Submitted by Julian Gold (EIS ’77)

44 officers

I was a member of the EIS cohort that reported to work on about July 3, 1978. The photo collage appears to be consistent with such standard photo compilations as created by other EIS cohorts and presented to the head of the EIS (prior to 1980, the Director of the Bureau of Epidemiology, and after 1980, the Director of the Epidemiology Program Office).

Submitted by Rick Goodman (EIS ’78)

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

20 officers

Worn out shoe leather with a prominent hole worn through was a recurring visual theme within the EIS. This is a reference to “shoe-leather” epidemiology– the practice of personally investigating disease outbreaks at the local population level and not relying on the reports of others.

Submitted by Clark Heath (EIS ’60)

32 officers

The inspiration for the piece came from a saying that Alex Langmuir would frequently use at the end of a particularly long day, “We’ll pick up the pieces in the morning.” This EIS class had more than usual amount of crises and each shard of the broken plate represents a crisis from those years. For example, “Smallpox in Grand Central” refers to a passenger returning to Canada who had Brazilian variola minor. This person passed through Grand Central Station in New York exposing numerous people to the virus. “Togetherness Lab Branch” refers to the fact that the director of CDC wanted better relations between the epidemiology branch and the laboratory branch. These branches were frequently at odds, because Alex wanted instant results from the lab. The final solution came when a lab was dedicated solely to support field epidemiology. “Fish Meal” refers to a Salmonella outbreak; it was one of the first occurrences of a major food contamination in the United States. “Zermatt, Vermont” was a misinterpretation of an assignment by an EIS officer who misheard the location of the outbreak over the phone. Many of the others refer to the growth and expansion of the program.

Submitted by Don Millar (EIS ’61)

23 officers

The Class of 1962 EIS plaque to Alex brings together three of Alex’s priorities:

- Alex was filled with a passion for strengthening the capacity and competency of young public health professionals (23 officers – 1 female and 22 males) in collecting and using evidence to improve the public’s health. (Left Half of Plaque- Alex’s EIS Class of 1962)

- Alexander felt strongly that the tools of surveillance and epidemiology should be used to address population issues, a major challenge to the future of the world. (Title-Overpopulation)

- Although CDC was a “domestic agency,” Alex had led CDC’s first international epi-investigation in 1958 (smallpox-East Pakistan), and saw a global need for use of epidemiology to identify and solve barriers to health and well-being. Seventeen of the 137 Epi-Aids from July 1962-June 1964 were international. (Right Half of Plaque – Photos from EIS Officers at Work)

- Cholera – Philippines, Vietnam

- Polio – Guyana, Marshall Islands, Democratic Republic, Barbados, Jordan

- Smallpox – Sweden

- Hepatitis – England

- Influenza – Jamaica, Taiwan

- Typhoid – Brazil

- Kerato-conjunctivitis – Bolivia

- Gastroenteritis – Truk Island

Submitted by Stan Foster (EIS ’62)

48 officers

The gift created by the 1963 EIS class was a plaque in the format of an ersatz monopoly board. Each property of the monopoly board was named for a place where members of the 1963 EIS class had carried out an epidemic aid investigation. In addition, there are flip-cards in the center of the monopoly board that called attention to foibles of CDC staff and EIS officers. It was presented to Dr. Langmuir on stage at the completion of the EIS Skit. When the flip-cards were read and the presentation completed, Dr. Langmuir responded by saying, “You rascals!” The creation of the plaque was led by Myron Schultz. The plaque hung on the wall of Dr. Langmuir’s office, along with other class plaques, until his retirement from CDC. It is presently on exhibit in CDC’s Global Health Odyssey Museum.

Submitted by Myron Schultz (EIS ’63)

30 officers

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

31 officers

First African-American officer

In our second year, eight members of the Epidemiology Program Office left for other opportunities. D.A. Henderson left for an opportunity with the World Health Organization and the smallpox eradication program. Bob Kaiser went to malaria eradication. John Witte moved to immunization. Don Millar, Mike Lane, and Leo Morris went to smallpox eradication. Jim Mosely moved to Foreign Quarantine; and Bruce Dull went to the office of the CDC Director. About half of the class stayed with CDC and filled in the gaps opened by those leaving. Inspiration was all around us– mid-level officers were disappearing right and left. Looking at the picture of Langmuir (the original picture of Alex Langmuir was replaced with the current one), note the saying “fairest of them all.” An old adage of Alex Langmuir’s was, “This is no democracy, but at least we can be fair to all.” And, he was, to a fault. He ran the show, and made the tough decisions when it came to assignments of us in our first year. In succeeding years, we saw his effort to hear out everyone on most tough decisions on who gets this or that investigation, position, or officer. He was tough, but fair to all of us.

Alan Hinman remembers the skit that year was based on Snow White. Alan played the part of Snow White (Alex Langmuir), and Lyle Conrad was Prince Charming (or some such title). Here are two verses of one of the songs, sung to a Gilbert and Sullivan tune.

When I was a youth in medical school,

I learned to obey this golden rule

Look wise, act smart, talk all the time,

And everyone will think that you are genuine!

CHORUS – and everyone will think that you are genuine!

And when you talk be sure to say

I this, I that, I every which way.

The result will be in your chosen field

That everyone will think that you’re a great big deal.

CHORUS – That everyone will think that you’re a great big deal!

Submitted by Lyle Conrad and Alan Hinman (EIS ’65)

72 officers

Measles was a dominant theme for the class of 1966. The EIS class of ’66 was the first large class of EIS officers with 72 officers; previous classes had far fewer. Indeed, our class was over twice as large as the immediately preceding class. The reason for this was that all those newly added positions were funded by the immunization program. Immunization made this unprecedented large investment because the new EIS officers were to be assigned to states in order to facilitate the implementation of the state measles immunization program. Live, attenuated measles vaccine had just been licensed, and this was an opportunity to conduct a national intervention to reduce the occurrence of measles dramatically and to control the disease– or even eliminate it. This was a great new challenge for CDC, and the class of ’66 (especially those of us assigned to states) were the “tip of the spear.”

Submitted by William Schaffner (proud member of the best EIS class ‘66)

68 officers

The plaque was developed near the end of our second year and presented to Dr. Alexander Langmuir, EIS Founder and Director in April 1969 at the evening skit during the EIS conference. EIS 1967 was the last class to experience the full two years with Dr. Langmuir. He “retired” the following year, but continued teaching epidemiology—first to Harvard medical students and subsequently at Johns Hopkins where he began his public health career. Dr. Phillip Brachman replaced Dr. Langmuir as EIS Director.

The theme of the gift was major public health events during our EIS period.

The cartoon depicts EIS Founder and Director Alexander Langmuir wielding a jet vaccinator, representing the launch of the US national measles immunization program, and intra-uterine coils, which had been licensed to prevent pregnancy and were being introduced into family planning programs in the USA (by CDC) and overseas (by USAID). Dr. Langmuir is confronting the targets of those campaigns–a distraught school boy and his anxious mother.

The four Afghani-like figures under the map of the USA are carrying flags which read “Pontiac” and “Hong Kong A2”.

“Pontiac” refers to the outbreak of an acute, severe, short-incubation, self-limited epidemic amongst employees of the Pontiac, Michigan Health Department when it re-opened after the July 4, 1967 long week end. The attack rate was nearly 100%, but there were no fatalities. EIS 1967 class members were pulled out of their class training to go to Pontiac and serve as guinea pigs (those not given masks became ill when the air conditioning was turned back on). This disparity convinced CDC leadership (i.e., Dr. Michael Greg) that the cause was a filterable infectious agent. It was not until 1977, however, that a CDC laboratory scientist (Dr. Joseph McDade) isolated the Legionella bacillus from specimens collected from the American Legion Bicentennial Convention at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia.

“Hong Kong A2” refers to the 1967-1968 H3N3 Influenza A Virus (current nomenclature) Pandemic that was first recognized in Hong Kong and spread rapidly around the world.

Submitted by Karl A. Western (EIS ’67)

53 officers

First Native American officer

The story behind this gift is missing. Please contact the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at history@cdc.gov if you have information about this gift.

46 officers

Our gift is a tongue-in-cheek reference to events that occurred during the two years that the class was at CDC (1969-1971). These include the introduction of rubella vaccine, which had unexpectedly severe side effects of arthritis; grave emerging problems with the strategic plans to eradicate measles and diphtheria; a year-long investigation of a nationwide outbreak of bacteremia produced by contaminated intravenous fluid; an investigation of higher than anticipated toxic effects on the liver by the administration of the drug isoniazid; and difficulties with the budget for the EIS program.*

I was assigned to Puerto Rico, and did not participate in creating the gift except to sign it. However, I can offer the following additions to John McGowan’s comments:

1. The title– “Philip S. Brachman has completed his first year of applied administrative epidemiology”– refers to the fact that Phil Brachman took over as Director of the Bureau of Epidemiology in 1970. So, he was in charge for one of our class’s two years in the EIS. This must have been the most administratively complex job he had held, and he had enormous shoes to fill. The only previous Director, and the Director during our first EIS year, was Alexander Langmuir.

2. The drawing of the bearded man is the new Director (Philip Brachman). He is kneeling before the image of Alexander Langmuir (the former Director), a God-like figure at CDC who was not known for his humility.

3. The “war in Pakistan to eliminate cholera” refers to the Bangladesh Liberation War that began March 26, 1971, near the end of our second year in the EIS. Before the war, Pakistan consisted of West Pakistan (now Pakistan) and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). In that war, East Pakistan gained its independence. and became Bangladesh. Of course, the war was not really fought to eliminate cholera—that was a joke. CDC was heavily involved in the Cholera Research Laboratory (CRL, later the ICDDR,B) in Bangladesh/East Pakistan, and the war must have been a concern for Phil Brachman. Our humor was somewhat strained! There may have a deeper meaning, such as the government of Bangladesh being more receptive to the activities of the CRL. But I was not involved in cholera then, and I don’t know about it.

4. Skiing: this appears to refer to the measles control program. Measles cases were dropping nicely with the use of vaccine, but then there was an unfortunate resurgence of cases. The epidemic curve (shown in the lower right corner) thus shows a nice down slope followed by a sudden hump. On the left, Phil is skiing happily down the down slope of the measles curve; then he skis along a relatively flat part of the curve; and then he runs into the upsurge, and is injured. On the right side, you see the rescue workers carrying his crumpled body up the slope of the increase in measles cases. In the upper right, you see Phil being treated with intravenous fluids. Unfortunately, the joke, as John described while we were EIS officers, was that Abbott intravenous fluids were found to be contaminated and to cause many illnesses. Poor Phil!

5. I’m not sure about the cartoon in the lower left corner, but it may refer to the new Family Planning Evaluation Division–I believe it was started in 1968 (the year before our class began) by Carl Tyler. I had nothing to do with that Division, but I have vague memories of there being some problems for the Division from right-wing politicians during our EIS years. But if so, why would Phil look so relaxed?

6. The cartoon in the upper left is a bit unclear, but I think it must refer to the country-wide rubella vaccine campaign that occurred during our two years in the EIS. Phil seems to be trying to lure a little boy over to be injected with the rubella vaccine. Phil is holding crutches, which probably refer to the fact that the rubella vaccine was found to cause arthritis in a fair number of recipients.

Submitted by *John McGowan and Paul Blake (EIS ‘69)

First EIS class

23 officers

22 physicians

1 sanitary engineer

The two simple leather soles exemplify the phrase “shoe-leather epidemiology,” a term Alex Langmuir used frequently. The term was defined as the practice of personally investigating disease outbreaks at the local population level, and not relying on the reports of others.

Because Alex Langmuir stressed shoe leather epidemiology, the term became closely associated with the Epidemic Intelligence Service. During the first year, one of the officers created a logo featuring the sole of a shoe with a prominent hole worn through the bottom, superimposed over the Earth. This logo has continued to be the symbol of the EIS.

17 officers

Alex Langmuir and the CDC/USPHS were contracted to conduct a “National Program for the Evaluation of Gamma Globulin for the Prevention of Poliomyelitis” during the last half of 1953. This necessitated intensive training of EIS officers near Pittsburgh that early summer in “muscle testing” – to enable us to measure the extent of paralysis of polio patients, some of whom had received gamma globulin before the onset of their polio. The program required that EIS officers, distributed across the US, visit every “multiple case household” to gather case histories, diagnostic specimens, and do muscle testing to assess the extent of neurologic damage, initially and 60 days later. My responsibility was for all such multiple case households in the state of Ohio. This work necessitated extensive travel throughout Ohio – to patient homes and regional hospital centers where severe cases with bulbar paralytic disease were gathered for respirator (iron lung) assistance for breathing – at Cleveland City Hospital, Maumee Valley Hospital in Toledo, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, etc.

By 1953, poliomyelitis was generally considered to be the most urgent disease problem in the nation, as mothers and fathers and the entire nation waited with great anxiety and impatience for the advent of an

effective preventive agent. Dr. Jonas Salk, with financial assistance from the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (NFIP), was progressing with the invention and production of a killed-virus vaccine, which became available for field testing the following year.

But in 1953, despite lack of clear evidence of the efficacy of immune globulin, physicians and communities were intensely competing for the limited supplies of immune globulin distributed by the State Health Departments. I recall an intense outbreak of polio in Miami County (Dayton), where the people panicked and vociferously demanded the bulk of Ohio’s entire supply of immune globulin. What a difficult time I had persuading them that its efficacy for prevention of polio was unknown, and that the state could not in fairness give them all they wanted. Their “panic in the streets” was very similar to that I encountered years later during a smallpox epidemic in Yorkshire, England. Altogether, the summer of 1953 was an active, challenging time for the Epidemic Intelligence Service. The EIS/CDC study of “Gamma Globulin for the Prevention of Poliomyelitis” did not reveal definitive utility, but it did help to “buy some time” until effective Salk polio vaccine became available for field testing in 1954.

The “inspiration” for the topic chosen was likely the rather bitter realization that after all the “muscle testing” training, extensive field work visiting multiple case households and hospitals, doing extensive muscle testing of cases, and extensive related communications, the results indicated that gamma globulin was ineffective for the prevention of poliomyelitis. A bust!

Submitted by Reimert T. Ravenholt, MD (EIS ’52)

11 officers

First veterinarian

The EIS conference was cancelled in 1955 so that an investigation of contaminated polio vaccine could be conducted. Later known as the Cutter incident, this investigation put CDC and EIS in the national spotlight for the first time.

32 officers

First nurse

First woman officer

First Asian officer

Our class project relates to the Cutter polio vaccine problem of April 1955. One or several batches of killed (Salk) polio vaccine produced by the Cutter Pharmaceutical Company was found to contain some live polio virus that had not been killed by their manufacturing process that included the use of formaldehyde to kill the virus. It was a major public health problem, and Dr. Langmuir reacted rapidly and with authority. The killed vaccine had been field tested in a program that was initiated in

1954 under the direction of Dr. Tommy Francis at the University of Michigan School of Public Health. The results of the field trial were announced in April of 1955, and the countrywide program to vaccinate children with the polio vaccine began within two weeks. The vaccine was produced by several different pharmaceutical companies. Within several weeks, a number of cases of polio were reported in children who had been vaccinated. This occurred just before the EIS conference for 1955, which was immediately cancelled. The majority of EIS officers became involved in investigating all cases of polio reported since the vaccination program was initiated. The investigations revealed that some vaccine produced by the Cutter Company did contain live virus. Obviously, the field investigations were very important in showing that only some vaccine from one company was contaminated with live virus. Thus, the national vaccination program could be restarted using vaccine produced by the other companies.

Our class decided that this event was the major event of our two years, and we prepared this plaque- a “Do it yourself polio vaccine kit.” The vaccine bottle was an actual polio vaccine bottle. The kit invites you to pour the vaccine into the metal cup and add formaldehyde to the level noted on the cup as to what magnitude of killed vaccine you want to attain, “Dead, Deader or Deadest.” You could then pull the “killed” vaccine into the syringe for use.

The esprit de corps within the EIS and importance of the class gift tradition are apparent in this class gift. While the whole class was deeply involved in the Cutter polio vaccine incident, the task of envisioning and assembling the plaque was delegated to another EIS officer who considered it “an honor to have been selected by his classmates to create and assemble the class plaque,” * even though he was in the class of 1955.

Submitted by Philip Brachman (EIS ’54)

*Submitted by Norm Petersen (EIS ’55)

1955

37 officers

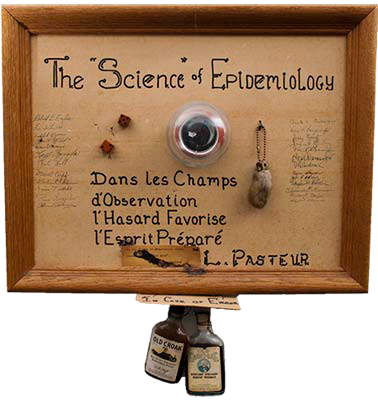

The symbolism on the plaque is quite straight forward: the irony of the Science of Epidemiology is the subject. The Pasteur quote “Dans les Champs d’Observation, l’Hasard Favorise l’Esprit Prepare” (In the field of observation, chance favors the prepared mind) is well-known and not infrequently referred to in the English. How much of epidemiology is science and how much is chance are suggested by the symbols of chance, which are represented by the crystal ball, a rabbit’s foot, and the dice. The meaning of the two small whiskey bottles at the bottom is less obvious. At that time, Alex Langmuir would frequently propose that whoever was wrong on a contentious issue would buy a bottle of whiskey to be consumed together with the winner of the wager. I don’t actually recall the wager ever actually being paid off, but the stated wager would come up perhaps a half a dozen times in a year.

Submitted by D. A. Henderson (EIS ’55)

17 officers

First dentist

First Hispanic officer

A possible explanation of the wave was the 1957 influenza epidemic of Asian flu. It came early that year to the U.S., in July and August. The flu was one of Alex’s favorite subjects, and he was always willing to bet a bottle of good scotch on what will happen next. He had been quoted in the newspapers of the day that flu this year would came early, and there will be “no second wave.” In fact, the flu came in the fall as usual, and it was twice as big as the summer wave. If you look at the EIS certificates, you see Alex Langmuir about to be engulfed in the second wave.*

The 1956 class was caught up in the polio epidemic, and Dr. Alex Langmuir sent us out to investigate polio-like outbreaks. It was a very scary time for everyone. I and two other members of our class were sent out from Atlanta to the CDC field station in Kansas City to respond to reported outbreaks of polio-like diseases. One such outbreak was in Mason City, Iowa. Our team was headed up by Dr. Tom Chin, and the laboratory in the field station was our backup. After examining numerous cases and processing many lab specimens, we concluded that we had experienced a coxsackie-B5 outbreak. The fact that we didn’t find any cases of permanent paralysis was a great relief to the community. I went on to Arizona to investigate an outbreak of a cluster of acute upper respiratory illnesses of viral origin.

When time permitted, we participated in a study of histoplasmosis, conducted by Dr. Leo Furcalo. He was concerned that some patients in TB hospitals might have been incorrectly placed there because they had histoplasmosis instead of TB. We found that to be true.

While I was at the Kansas City Field station, I also was given responsibility for surveillance of equine encephalitis cases in six Midwestern states. I continued that function when I returned to Atlanta.

Submitted by John Greene (EIS ’56)

* Submitted by Lyle Conrad (EIS ’65)

21 officers

According to classmates Malcolm Page and Paul Leaverton, assigned to CDC in Atlanta, and W. Paul Glezen, assigned to the North Carolina State Health Department, this gift reflects the first major international epidemic aid response undertaken by an EIS team– the trip to East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) for the smallpox epidemic. Originally, the State Department was not sure about offering help until it heard that the Soviets were sending a team of scientists. Alex was proud of the effort. In his opinion, the EIS team that had spread out to villages to deliver vaccine had a greater benefit than the USSR entourage that arrived in two large cargo planes with a lot of elaborate laboratory equipment, etc. In other words, the EIS team represented real “shoe-leather” epidemiology. The plaque was a good comment on the endeavor. The octopus symbolizes the extension of CDC “surveillance” worldwide.

Submitted by W. Paul Glezen (EIS ’57)

17 officers

Alex Langmuir was always a big thinker and required his EIS officers to think just as big.

This class plaque is a tongue and cheek reference to Alex’s “big thinking”. Epidemiological surveillance at the time was directed to the state and local public health departments, Alex wanted to expand surveillance to include international programs. May of 1958 saw the launch of Sputnik, the first man-made satellite to orbit the earth, and so many people started to think about other worlds. The class made this plaque with the future of epidemiology and space in mind, to expand surveillance into space using Epi satellites. The satellite in the upper left of the plaque is suitably named X-ADL, in honor of Alex Duncan Langmuir. It was of the opinion of the class that Alex’s epidemiological surveillance should not just be confined to the local and state health departments but to the whole planet Earth and perhaps beyond. It turned out actually that over the next decade CDC was involved in “orbital” surveillance during the first moonshot. There is a small inscription on the bottom of the plaque that refers to Alex’s ambitions to take the EIS program internationally-and possibly into orbit as the inscription reads;

The last decade went round and round, how difficult to absorb it. But as the next decades goes by, may you always be in orbit.

Submitted by Andy Nahmias (EIS ’58)

24 officers

In February 1961, Jim Mason was sent to Pascagoula, Mississippi in response to a request for assistance in investigating an apparent outbreak of infectious hepatitis (now hepatitis A). In very short order– 11 days, he established that it was due to the ingestion of raw oysters that had been harvested from sewage-contaminated waters at the mouth of the Pascagoula River. Jim reported on this outbreak at the 1961 EIS Conference. Shortly after the Pascagoula outbreak, an increased incidence of hepatitis was noted in the New York/New Jersey area; this was eventually traced to the ingestion of raw clams in sewage-contaminated waters in Raritan Bay, New Jersey. These two outbreaks initiated the era of shellfish-associated hepatitis; hence, the clam on Alex’s nose.

A little further history is in order: the first shellfish-associated hepatitis outbreak had been reported from Sweden in 1956, and was traced to oysters. The Pascagoula outbreak was the first reported from the United States. After this outbreak had been recognized, the Hepatitis Surveillance Unit looked at the distribution of infectious hepatitis cases, and identified clusters of adult male cases in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Upon investigation, many of these cases had a history of eating raw shellfish, which had been harvested from certain parts of Raritan Bay. Jim Mason spent some time in New York City after the EIS conference checking harvesting and shipping data on clams in the Fulton Fish Market. Only a small fraction of the total harvest came from polluted areas, and was capable of transmitting hepatitis. Jim feels that such shellfish-associated hepatitis had probably been occurring for years, but the transmission mode had simply not been identified until 1961.

“Hard-Nosed Epidemiologist” was a term Alex used frequently (though not nearly as often as “shoe- leather epidemiology”), probably referring to the determination required of EIS officers to dig deeply for data, often by learning how to get around various administrative roadblocks placed in the way.

“On the New Frontier” was a term of uncertain origin; we think it may refer in some way to the new JFK

administration, which had recently come to power in Washington.

Submitted by Ted Eickhoff, Bill Marine, Jim Mason and Leo Morris (EIS ’59)