At a glance

The domestic medical screening guidance is for state public health departments and healthcare providers in the United States who conduct the initial medical screening for refugees. These screenings usually occur 30-90 days after the refugee arrives in the United States. This guidance aims to promote and improve refugee health, prevent disease, and familiarize refugees with the U.S. healthcare system.

Overview

- Review local confidentiality laws with all adult and adolescent patients and explain how confidentiality covers sexual and reproductive health histories, examinations, and testing.

- Urine pregnancy test should be performed for all women of childbearing age and pubescent adolescent girls. Repeat pregnancy test if date of last sex without a condom is within 14 days and first test was negative (if menses is not reported since last sex without a condom). Refer women and adolescent girls who are pregnant and wish to continue with their pregnancy to an obstetric provider.

- Discuss family planning and available contraceptive methods, including accessibility, efficacy, and cost. Condoms should be offered to avoid unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

- A complete evaluation for all STIs, including a thorough medical history, physical examination, and disease-specific testing (as recommended), should be conducted. Consider testing any refugee (including children) who has a history of sexual assault (including incest or underage marriage).

- Screen women and girls from countries where female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) is practiced for possible FGM/C-associated medical complications, including chronic pain, recurrent urinary tract infections, and obstetric issues.

- Clinicians should inform refugees that FGM/C is considered child abuse, and that it is illegal to perform FGM/C on a child in the United States or to take a child out of the country to undergo the procedure ("vacation cutting").

- Clear documentation of FGM/C in the medical record soon after US arrival, including a description of physical findings and ICD-10 coding, may help protect against future suspicions of "vacation cutting" and abuse accusations.

- Clinicians should inform refugees that FGM/C is considered child abuse, and that it is illegal to perform FGM/C on a child in the United States or to take a child out of the country to undergo the procedure ("vacation cutting").

Background

The Sexual and Reproductive Health Screening Guidance is intended to provide clinicians with best practices for diagnosing STIs in refugees, and describe how to discuss safe sex practices, consent, local laws concerning age of consent for sexual intercourse, contraception and family planning, and standard gynecological care with refugees. As with any patient population, topics related to sexual and reproductive health may be viewed as highly personal. Refugees may have varied levels of understanding of sexual anatomy and reproductive health, including STIs and available contraceptive methods. The prevalence of STIs in refugee populations is not well characterized. It is important to consider STIs to minimize or prevent acute and chronic sequelae, as well as prevent transmission to others through condom use or abstinence.

Overseas Medical Examination

The overseas medical history and physical examination includes a search for signs and symptoms consistent with STIs; however, many STIs may be asymptomatic.

All applicants aged 18 years to those aged less than 45 years must be tested for evidence of syphilis using nontreponemal and treponemal laboratory tests. Applicants aged less than 18 years or greater than 45 years must be tested if there is reason to suspect infection with syphilis. Syphilis serologic testing (including confirmatory testing, if warranted) is done according to the CDC Technical Instructions for Syphilis for Panel Physicians. An external genital exam is not performed unless there is a medical history suggestive of recent syphilis diagnosis, physical examination findings consistent with early syphilis (e.g., rash, oral lesions), or positive nontreponemal and treponemal test results.

All applicants aged 18 to 24 years must be tested for evidence of gonorrhea via nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). Applicants aged less than 18 years or greater than 24 years must be tested if there is a reason to suspect infection with gonorrhea. Gonorrhea testing is done according to the CDC Technical Instructions for Gonorrhea for Panel Physicians. Details of testing and treatment for syphilis and gonorrhea must be documented on the DS-3026 (Medical History and Physical Examination Worksheet).

Those with a positive (or reactive) nontreponemal screening test (i.e., RPR or VDRL) and a positive treponemal-specific confirmatory test are Class A for syphilis. Individuals with untreated gonorrhea are classified as Class A. Upon successfully completing treatment for syphilis or gonorrhea, individuals are reclassified as Class B and permitted to travel.

Chlamydia trachomatis testing is not required (as it is not a disease of public health significance under 42 Code of Federal Regulations Part 34). However, many panel physicians use testing kits that screen for both chlamydia and gonorrhea. When these tests are used, panel physicians are directed by CDC to document the test results in the remarks section of the DS-3026. If an applicant tests positive for chlamydia, treatment should also be documented on the remarks section of the DS-3026 and the applicant should be given a "Class B Other" classification for chlamydia infection.

In January 2010, HIV was removed from the list of inadmissible conditions and is no longer routinely tested for overseas. Refugees who are diagnosed with syphilis or gonorrhea prior to departure are offered HIV testing. If a refugee discloses an HIV diagnosis, that information along with current medication regimen, is recorded on the DS forms. As of March 2016, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venerum, and granuloma inguinale were also removed from the list of communicable diseases of public health significance. Therefore, evaluation for these diseases is no longer performed as part of the overseas US immigration medical screening process. For additional information, please see Part 34 Final Rule, issued on January 2016.

Additionally, female refugees are routinely checked for pregnancy during the overseas medical examination with a urine pregnancy test. Pregnancies are reported on the DS-2054 (Report of Medical Examination by Panel Physician) and DS-3026. As live-attenuated vaccines and some presumptive treatments for parasitic infections are contraindicated during pregnancy, contraindications should be noted on the DS-3025 (Vaccination Documentation Worksheet) as well as the DS-3026.

Guidance for Post-Arrival Screening and Evaluation

In addition to screening for pregnancy and STIs, clinicians should discuss family planning, available contraceptive methods, condom use to protect against STIs, and provide general education on sexual health and wellness. This information should be provided confidentially to each patient, and clinicians should approach these discussions in a patient-centered manner that is neither directive nor coercive. Education should be provided so that all new arrivals understand that each person has a right to access healthcare, that adults can make independent decisions about their health (including reproductive and sexual health), and that these decisions are protected by US confidentiality laws. Adolescents should be made aware that they are entitled to make independent decisions about their sexual health, and that their health information is confidential. However, it is important to note that confidentiality laws pertaining to adolescent reproductive and sexual health, including contraception choices, vary by state1.

Pregnancy Testing and Initial Prenatal and Postpartum Care

Pregnancy testing should be performed at the initial screening examination for all women of childbearing age and pubescent girls. Pregnancy testing (including a confirmatory test if indicated, as described below) should be conducted as part of the medical screening and prior to imaging or medical treatments that may be contraindicated in pregnancy (such as live-attenuated vaccines and certain medications).

At the initial screening examination, clinicians should conduct a urine pregnancy test and document the date of last sexual intercourse without a condom for all patients among whom pregnancy is possible. If pregnancy test is negative, and the patient reports sex without a condom within the last 5 days, is not currently on menses, and does not desire pregnancy, offer emergency contraception234.

If initial urine pregnancy test is negative, but last sex without a condom occurred 6-14 days ago and refugee reports menses since last sex without a condom, there is no need to repeat the urine pregnancy test3. However, if the refugee does not report menses since last sex without a condom, repeat urine pregnancy test at 14 days after last sex without a condom. If patient does not desire future pregnancy, provide contraceptive counseling and offer available contraceptive methods (see Family Planning and Contraception), including condoms. If the repeat urine pregnancy test is negative, administer vaccines and provide medications, as indicated.

If the urine pregnancy test is positive, the refugee should be referred to a clinician who provides obstetric care for management of the pregnancy. If the patient is pregnant or trying to become pregnant, the initial screening visit is a good opportunity to discuss the importance of preconception care, prenatal vitamins, appropriate gestational weight gain, and vaccinations, as well as addressing underlying medical conditions, tobacco and alcohol use, and mental health issues. Screening clinicians should also emphasize the importance of establishing a medical home for ongoing health needs.

Pregnant and lactating patients should be screened for lead exposure with a blood test (see Domestic Lead Screening Guidance). Additionally, clinicians should council women and adolescent girls on the importance of taking a multivitamin that includes folic acid and vitamin D.

If a refugee patient has recently given birth (either domestically or overseas), issues or questions related to the postpartum period such as depression and breastfeeding should be evaluated or addressed.

Family Planning and Contraception

Refugees may have had limited access to contraception and may not be aware of their options. Clinicians are encouraged to discuss family planning and provide information about available contraceptive methods, including accessibility, efficacy, and cost. Essential components of quality counseling around family planning must include client-centered counseling and shared decision-making5.

When first discussing family planning, it is important to discuss with the patient alone, and then if they desire, with their partner present (if they have one). Clinicians should be aware that in some cultures, the husband makes family planning decisions. This conversation could begin with:

- "Are you interested in having (more) children?"

- "Have you thought about how many children you might want, and when?"

Condoms should be offered to the patient and their partner at the initial visit for pregnancy and STD prevention. If the patient would like to wait before having more children or does not want to have children, offer contraceptive counseling and discuss available contraceptive methods. As with the general patient population, long-acting reversible methods of contraception (intrauterine devices and implants) are the most effective67. Contraceptive pills, patches, rings, and injectables are moderately effective. Barrier methods, fertility-awareness methods, withdrawal, and lactational amenorrhea (prolonged exclusive breastfeeding) are less effective for pregnancy prevention. Some women and adolescent girls may want to consult with their partner or family members before making decisions. Therefore, clinicians should allow time for this discussion to occur and provide opportunities to re-engage in these discussions at subsequent visits.

Clinicians should explain that in the United States, women and adolescent girls have the right to access sexual and reproductive health services, including contraception. Education should be provided so that all new male arrivals understand that women (including adolescents) have a right to make independent decisions about their health (including sexual and reproductive health), and that these decisions are protected by US law. Men and adolescent boys also have these same rights and protections. Clinicians should also be aware that consent and confidentiality laws vary among states, and should provide counseling about consent and confidentiality to all adolescent patients.

Additional information, including Contraceptive Guidance for Health Care Providers, is available from the CDC Division of Reproductive Health.

Screening for Sexually Transmitted Diseases

The following STIs should be considered during the post-arrival medical examination:

- Syphilis

- Chlamydia

- Gonorrhea

- Chancroid

- Granuloma inguinale/donovanosis

- Lymphogranuloma venereum

- Genital herpes

- Genital warts

- Trichomoniasis

- HIV (see the HIV Domestic Screening Guidance)

A complete evaluation for all STIs includes a thorough medical history, physical examination, and, for specific infections, testing, as many infections are asymptomatic. The optimal medical history includes asking about sexual history, including any contact with a person who has, or had, a known STI, and asking about any history of signs or symptoms suggestive of an STI. This is usually done with the patient alone, rather than with other family members present. Common signs and symptoms of infection include urethral, vaginal, or rectal discharge; dysuria; rash; sores on the genitals, anus, or mouth; or a rash on the palms or soles of the feet. Pertinent elements of the physical examination for STIs include palpation for enlarged or tender lymph nodes, inspection of skin and oral mucosa, and an external anal and genital examination, including inspection for discharge, ulcers, or rashes. In refugees who previously experienced trauma (e.g., sexual assault victims), the external anal and genital examination may be postponed until the refugee establishes a trusting relationship with a clinician. Clinicians should ensure that follow-up is completed in a timely manner, and that postponing the external exam does not delay management and treatment of acute medical issues. If an individual has had a high-risk exposure (such as rape), it is important to determine an approximate exposure date. As conversion from exposure can take several months for some infections (including some viral hepatitides, syphilis, and HIV), refugees should be retested for infection 3 months after potential exposure8.

Consider testing any refugee (including children) who has a history of sexual assault (including incest or a history of underage marriage) for STIs. Management and evaluation of sexually assaulted children requires consultation with an expert8. Clinicians should also be aware that adolescent refugees may be reluctant to disclose that they are sexually active due to stigma and/or privacy concerns. Therefore, some pediatricians favor universal rather than risk-based screening. In many regions of the world, adolescents are unable to legally consent for confidential sexual and reproductive healthcare, and confidential adolescent healthcare is non-existent. Clinicians should ensure that adolescent refugees understand the confidential nature of clinic visits to discuss sexual and reproductive care and how to access appropriate services. Clinicians should also be aware that consent and confidentiality laws vary among states, and should provide counseling about consent and confidentiality to all adolescent patients.

HIV testing is also strongly encouraged in newly arriving refugee populations according to current CDC Guidance for Screening for HIV Infection during the Refugee Domestic Medical Examination. Testing for HIV is particularly important and encouraged for any refugee with another confirmed STI. Healthcare providers should provide counseling to all patients with STIs, including HIV, as well as evaluation of and treatment for their sexual partners. Information should be provided about preventative measures and risk reduction interventions should be tailored to each individual's risk behavior9.

Disease-Specific Testing

Syphilis

Syphilis screening tests should be performed routinely for refugees in the following categories:

- All refugees aged 18 years to those aged less than 45 years, if no overseas results are available.

- Refugees 45 years and older, if there is reason to suspect infection.

- Refugees younger than 18 years of age who are at risk for congenital syphilis (i.e., mother who tests positive for syphilis, if the mother's syphilis results are not available, or the child is unaccompanied), who disclose sexual activity, or have been sexually assaulted should be evaluated according to the CDC Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2021.

Serologic testing for syphilis requires the use of two tests. A nontreponemal test, such as venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test or rapid plasma reagin (RPR), may be used for screening. Positive nontreponemal test results should be confirmed using a treponemal test (e.g., Treponema pallidum passive particle agglutination assay [TP-PA], various enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays [EIAs or ELISAs], chemiluminescence immunoassays). Table 1 describes the interpretation of syphilis serology test results. The use of only one type of test is insufficient for diagnosis, since all tests have limitations, including the possibility of false-positive test results. False-positive nontreponemal test results can also be associated with various medical conditions unrelated to syphilis, including autoimmune disorders, older age, and injection drug use. The use of a "reverse screening" algorithm (e.g., initial screening with a treponemal test, followed by nontreponemal testing) is another option for serologic testing when it is being used as a local standard of care. Further evaluation, including evaluation for neurosyphilis, and treatment should be instituted in patients with a positive screening test, according to the CDC Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021.

Table 1. Interpretation of Syphilis Serology Tests

| Nontreponemal Test | Treponemal Test | Interpretations and Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Nonreactive* | Nonreactive | No evidence of syphilis |

| Reactive | Reactive |

|

| Reactive | Nonreactive | False-positive result may be seen in certain acute or chronic infections (e.g., tuberculosis, hepatitis, malaria, early HIV infection), autoimmune diseases (e.g., systemic lupus, rheumatoid arthritis), injection drug use, pregnancy, and following vaccination (e.g., smallpox, MMR). |

| Nonreactive | Reactive |

Note: After successful treatment, a positive nontreponemal test usually becomes negative, whereas a positive treponemal test usually remains positive for life. |

*Note: Nontreponemal testing may have a false-negative result during primary syphilis in the very early stages and during tertiary syphilis in the very late stages. Suggest presumptive treatment and retesting if clinical suspicion is high. See the CDC Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines.

Syphilis in children (either congenital or acquired) must be properly evaluated. The diagnosis of congenital syphilis is complicated by transplacental transfer of maternal nontreponemal and treponemal IgG antibodies to the fetus. Therefore, it is difficult to interpret reactive serologic tests for syphilis in newborns born to mothers seropositive for syphilis. Further information on evaluation for congenital syphilis is published in the CDC STI Treatment Guidelines (2021) and the American Academy of Pediatrics Red Book. Infants and children who have a reactive serology should be examined and have maternal serology and records reviewed to assess whether they have congenital or acquired syphilis.

Chlamydia and Gonorrhea

NAATs are recommended for the following groups:

- All refugees aged 18 to 24 years who do not have documented pre-departure testing

- All refugees aged less than 18 years or greater than 24 years must be tested if there is a reason to suspect infection, or if there are risk factors, such as a new sex partner or multiple sex partners, sex partner with concurrent partners, or sex partner who has a sexually transmitted infection.

- Female refugees with abnormal vaginal or rectal discharge, intermenstrual vaginal bleeding, or lower abdominal or pelvic pain

- Male refugees with urethral discharge, dysuria, or rectal pain or discharge

Additional Resources

Further information on specific STIs, including treatment and laboratory guidance, is available at:

- CDC STD website

- CDC STD Treatment website

- CDC Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021

- Screening for Chlamydia and Gonorrhea: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement

Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting

Some refugee women and girls may have experienced, or be at risk for, female genital mutilation or cutting (FGM/C). WHO defines FGM/C as any procedure that involves partial or total removal of external female genitalia or other injury to female genital organs for cultural or nontherapeutic reasons1011. FGM/C is a cultural custom, not a religious tenet. However, some community members may be led to believe that FGM/C is religiously prescribed. Communities that practice FGM/C often believe that FGM/C will ensure a girl's proper upbringing, preserve family honor, and/or make a girl suitable for marriage12. FGM/C is deeply engrained in some cultures and is not isolated to one ethnic or religious group. It is estimated that more than 200 million women worldwide have undergone FGM/C1011. The age at which FGM/C is performed varies among countries, as well as communities. In some instances, FGM/C is performed in children from infancy to 5 years of age, but in others, FGM/C is performed in older girls and adolescents, and rarely, just prior to marriage131415. FGM/C has been reported in more than 30 countries, including numerous countries where refugees originate. The majority of cases occur in parts of East and West Africa, as well as select countries in Southeast Asia, North Africa, and the Middle East1011. Although rarely performed in the United States, it is estimated that more than 500,000 women and girls are at risk for FGM/C or may have undergone the procedure, with 50% of those at risk originating from Egypt, Ethiopia, and Somalia1617. However, many migrate to the United States from countries where FGM/C is known to occur, but prevalence is unknown (e.g., Indonesia and India). Therefore, the true number of women and girls at risk for FGM/C in the United States may be higher17.

FGM/C has no known health benefits and can result in both immediate and long-term sequelae (Table 2). FGM/C is associated with many health complications including severe bleeding, difficulty urinating, cysts, and infection (including viral hepatitis and HIV), as well as complications during childbirth and increased risk of newborn death. Due to the time between when the procedure is usually performed and US arrival, US clinicians are more likely to see patients with long-term complications.

Table 2. Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting Complications

| Early Complications | Long-Term (Late) Complications | Obstetric Risks and Complications |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Source: Nour et al 200818, World Health Organization 201610

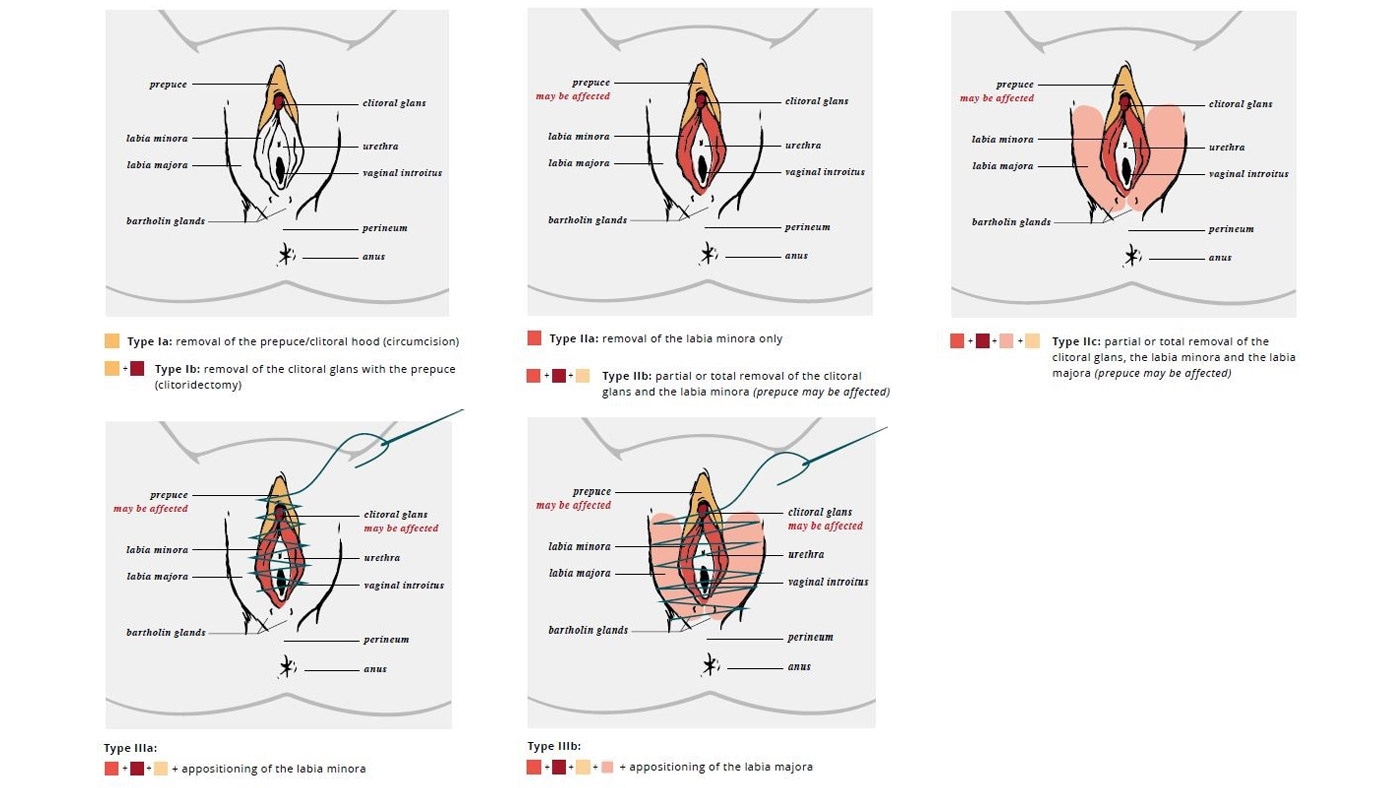

The WHO has defined 4 types of FGM/C: types I and II (sometimes referred to as Sunna), type III (also known as pharaonic), and type IV (Table 3). The long-term health complications are type-specific, with increasing morbidity associated with increasing severity and extent of tissue excision. Many women and girls may not experience any complications, particularly with types I and II. The most serious complications are generally seen in women and girls with type III. Figure 1 includes drawings of types I, II, and III FGM/C. However, clinicians should be aware that female anatomy may vary, and some patients may present differently.

Table 3. FGM/C Types and Clinical Description

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Type I (“Sunna”) | Partial or total removal of the clitoral glans (clitoridectomy) and/or the prepuce |

| Type II (“Sunna”) | Partial or total removal of the clitoral glans and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora (excision) |

| Type III (“Pharaonic”) | Narrowing of the vaginal opening with the creation of a covering seal by cutting and appositioning the labia minora or labia majora with or without excision of the clitoral prepuce and glans (infibulation) |

| Type IV | All other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, for example pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterization |

Source: World Health Organization 2018 13

Figure 1. Clinical Drawings of FGM/C Types I, II, and III

Most experts recommend screening women and girls from countries where the practice is prevalent for possible FGM/C-associated medical complications (including chronic pain, recurrent urinary tract infections, and obstetric issues)1219202122. When discussing FGM/C with patients, it is critical that clinicians employ a non-judgmental, straightforward approach (e.g. asking about history of "circumcision or cutting" as one of many questions when obtaining past medical history), and should be knowledgeable about FGM/C, cognizant of their own views on FGM/C, and aware of how their opinions may affect verbal communication and body language22.

Start conversations on FGM/C with information-gathering questions before more intimate and sensitive questions, framing questions carefully so that the patient does not feel that she is being interrogated22. A thoughtful and open approach will allow clinicians to discern the patient's awareness and of FGM/C (some individuals may not be aware that they have undergone the procedure), level of concern, cultural value of the practice, and health goals. Clinicians engaging in this dialogue are encouraged to use silences and allow for patients to take their time responding to questions22. Clinicians should educate patients and caregivers (in pediatric cases) about possible medical complications related to FGM/C, including the need for urgent evaluation if signs or symptoms of urinary obstruction or pyelonephritis develop.

It is important that new refugee arrivals from countries where FGM/C is widely practiced receive education regarding US laws and available health and social services. FGM/C is considered child abuse and is a reportable condition in the United States, and federal and state laws protect girls from FGM/C. Clinicians should explain that it is illegal to perform FGM/C on a child in the United States, and that it is illegal to take a child out of the country to undergo the procedure ("vacation cutting")15. Additional information on US laws related to FGM/C is available:

- Center for Reproductive Rights

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

- U.S. Code, Title 18, Part I, Chapter 7, 116

It is critical to develop relationships with social service agencies and health professionals who have expertise in working with FGM/C-affected communities. These relationships can help facilitate timely referral, answer questions, provide additional counseling and information, and address health concerns as they arise. Referrals should be documented in the medical record, in addition to findings of FGM/C and ICD-10 code, as well as documentation of communication with all providers involved. Women and girls who have undergone FGM/C may require a care team including any of the following specialists: obstetrician/gynecologists (including adolescent gynecology), urogynecologists, urologists, sexologists, mental health professionals, and physical therapists12.

Pediatric Considerations

External genital exams are an important component of the refugee health screening for all pediatric patients23. Providers should explain the exam to children and caregivers, particularly mothers, and obtain consent. If FGM/C is identified, findings must be documented in the medical record, including type of FGM/C and ICD-10 code. Clear documentation, including a detailed description of physical findings of FGM/C soon after arrival in the United States, may help protect families against suspicions of "vacation cutting" or future abuse accusations. Caregivers and/or the child may request to defer the genital exam for a future visit, with assurance that timely follow-up will occur. The deferred exam should also be documented. FGM/C (particularly type I) may be difficult to identify in prepubertal children. Additionally, types II and III may be difficult to distinguish from labial adhesions in very young children15. Clinicians should ensure that caregivers and adolescents are aware of potential medical complications, including the need for urgent evaluation if signs or symptoms of urinary obstruction or pyelonephritis develop. If complications are identified, refer children to a gynecologist or urologist with experience caring for children with FGM/C.

Additional Resources

Bridging Refugee Youth & Children's Services (BRYCS) has developed a series of tools and resources focused on FGM/C among refugees. These materials, some of which are available in languages spoken by refugees, may be helpful for clinicians who screen or treat refugee patients.

The WHO has developed a clinical handbook, "Care of Girls and Women Living with Female Genital Mutilation," which may be helpful for providers.

The Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center at Arizona State University has also published a visual reference and learning tool for health professionals on Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C).

Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in Children and Adolescents: Illustrated Guide to Diagnose, Assess, Inform and Report guides healthcare professionals in diagnosis, clinical management, patient-provider communication, as well as recording and reporting of FGM/C. The chapter, "Assessing the Infant/Child/Young Person with Suspected FGM/C" includes an illustrated multidisciplinary guide on FGM/C in children and adolescents."

Further information on FGM/C is available from the CDC Division of Reproductive Health.

- Guttmacher Institute. An Overview of Consent to Reproductive Health Services by Young People. 2020; Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/overview-minors-consent-law.

- Hoopes, A.J., et al., 2016 Updates to US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use and Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use: Highlights for Adolescent Patients. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol, 2017. 30(2): p. 149-155.

- Curtis, K.M., et al., U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep, 2016. 65(4): p. 1-66.

- Curtis, K.M., et al., U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep, 2016. 65(3): p. 1-103.

- Gavin, L., K. Pazol, and K. Ahrens, Update: Providing Quality Family Planning Services – Recommendations from CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2017. 66(50): p. 1383-1385.

- Practice Bulletin No. 186: Long-Acting Reversible Contraception: Implants and Intrauterine Devices. Obstet Gynecol, 2017. 130(5): p. e251-e269.

- Contraceptive Technology. Contraceptive Efficacy. [cited 2020 August 8]; Available from: http://www.contraceptivetechnology.org/the-book/take-a-peek/contraceptive-efficacy/

- Workowski, K.A., et al., Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep, 2021. 70(4): p. 1-187.

- O'Connor, E.A., et al., Behavioral sexual risk-reduction counseling in primary care to prevent sexually transmitted infections: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med, 2014. 161(12): p. 874-83.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on the management of health complications from female genital mutilation. 2016; Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/fgm/management-health-complications-fgm/en/

- World Health Organization. Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). [cited 2019 February 12]; Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/fgm/prevalence/en/

- Mishori, R., N. Warren, and R. Reingold, Female Genital Mutilation or Cutting. Am Fam Physician, 2018. 97(1): p. 49-52.

- World Health Organization, Care of Girls & Women Living with Female Genital Mutilation: A Clinical Handbook. 2018.

- UNICEF, Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change 2013.

- Young J, et al., Diagnosis, Management, and Treatment of Female Genital Mutilation or Cutting in Girls. Pediatrics, 2020. 145(6).

- Office on Women's Health. Female genital mutilation or cutting. 2018 [cited 2019 February 5]; Available from: https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/female-genital-cutting

- Goldberg, H., et al., Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in the United States: Updated Estimates of Women and Girls at Risk, 2012. Public Health Rep, 2016. 131(2): p. 340-7.

- Nour, N.M., Female genital cutting: a persisting practice. Rev Obstet Gynecol, 2008. 1(3): p. 135-9.

- Nour, N.M., Female genital cutting: clinical and cultural guidelines. Obstet Gynecol Surv, 2004. 59(4): p. 272-9.

- Hearst, A.A. and A.M. Molnar, Female genital cutting: an evidence-based approach to clinical management for the primary care physician. Mayo Clin Proc, 2013. 88(6): p. 618-29.

- Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists, Female Genital Mutilation and its Management, Green-Top Guideline No. 53. 2015.

- Resolution, Female Genital Mutilation Screening Toolkit. 2016.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Immigrant Child Health Toolkit.