Disparities in Stressful Life Events Among Children Aged 5–17 Years: United States, 2019

NCHS Data Brief No. 416, September 2021

PDF Version (415 KB)

- Key findings

- What percentage of children aged 5–17 years were exposed to violence in their neighborhood, and did this vary by sociodemographic characteristics?

- What percentage of children ever lived with a parent or guardian who served time in jail or prison, and did this vary by sociodemographic characteristics?

- What percentage of children aged 5–17 years ever lived with someone who was mentally ill or severely depressed, and did this vary by sociodemographic characteristics?

- What percentage of children aged 5–17 years ever lived with someone with an alcohol or drug problem, and did this vary by sociodemographic characteristic?

- Summary

Data from the National Health Interview Survey

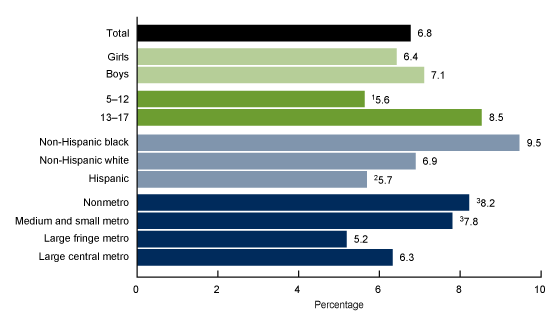

- In 2019, 6.8% of children aged 5–17 years were victims of or witnessed violence in their neighborhood with exposure varying by age, race and Hispanic origin, and level of urbanization.

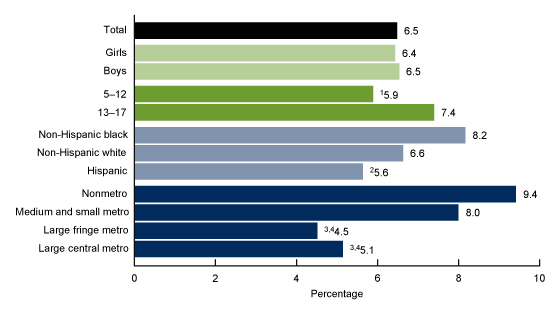

- The percentage of children aged 5–17 years who had lived with a parent or guardian who served time in jail or prison increased with age and varied by sociodemographic characteristics.

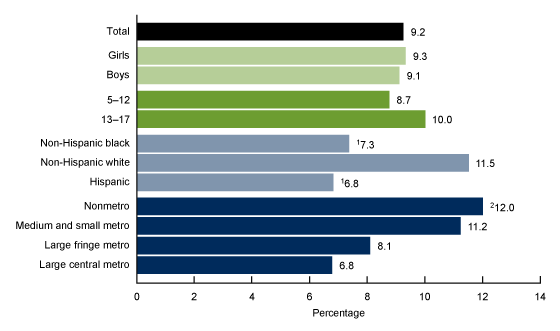

- The percentage of children who had lived with someone who was mentally ill or severely depressed varied by race and Hispanic origin and urbanization level.

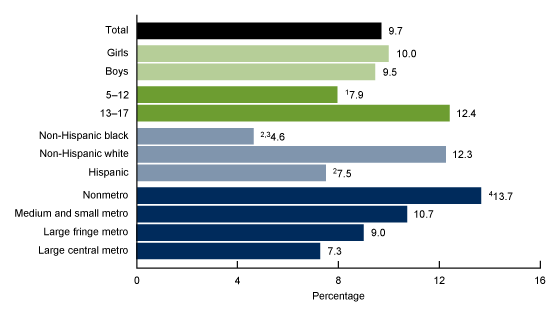

- Among children aged 5–17 years, 9.7% had lived with someone with an alcohol or drug problem, and the percentage differed by age, race and Hispanic origin, and urbanization level.

Stressful life events in childhood include various forms of abuse, neglect, and household instability, such as violence exposure, parental incarceration, or living with someone with mental health, alcohol, or drug problems (1). These events are key social determinants of a child’s well-being and can have lifelong impacts on physical and mental health (2–9). This report presents sociodemographic disparities in stressful life events as reported by a knowledgeable adult, usually a parent, among children aged 5–17 years using the 2019 National Health Interview Survey data.

Keywords: violence, mental health, alcohol or drug problem, National Health Interview Survey (NHIS)

What percentage of children aged 5–17 years were exposed to violence in their neighborhood, and did this vary by sociodemographic characteristics?

- In 2019, 6.8% of children aged 5–17 years were exposed to neighborhood violence, either as victims or witnesses (Figure 1).

- No significant difference in exposure to violence was observed between boys and girls.

- The percentage of children who were exposed to violence in their neighborhood increased with age, from 5.6% among those aged 5–12 years, to 8.5% among those aged 13–17 years.

- Non-Hispanic black children (9.5%) had higher rates of violence exposure than Hispanic children (5.7%). The observed difference between non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic white children and Hispanic and non-Hispanic white children was not significant.

- Violence exposure was lower among children in large fringe metropolitan areas (5.2%) and large central metropolitan areas (6.3%) compared with children in nonmetropolitan areas (8.2%) and in medium and small metropolitan areas (7.8%), although the observed difference with large central metropolitan areas was not significant.

Figure 1. Percentage of children aged 5–17 years who had been exposed to violence, by sex, age group, race and Hispanic origin, and urbanization level: United States, 2019

1Significantly different from children aged 13–17 years (p < 0.05).

2Significantly different from non-Hispanic black children (p < 0.05).

3Significantly different from children in large fringe metropolitan areas (p < 0.05)

NOTES: Violence exposure is based on responses by a knowledgeable adult, usually a parent, to the survey question, “Has (child) ever been the victim of violence or witnessed violence in his/her neighborhood?” Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the civilian noninstitutionalized U.S. population. Access data table for Figure 1.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2019.

What percentage of children ever lived with a parent or guardian who served time in jail or prison, and did this vary by sociodemographic characteristics?

- In 2019, 6.5% of children aged 5–17 years had lived with a parent or guardian who served time in jail or prison (Figure 2).

- No significant difference in parental or guardian incarceration was observed between boys and girls.

- The percentage of children who ever lived with a parent or guardian who served time in jail or prison increased with age, from 5.9% among those aged 5–12 years to 7.4% among those aged 13–17 years.

- A higher percentage of non-Hispanic black children (8.2%) had lived with a parent or guardian who served time in jail or prison compared with Hispanic (5.6%) and non-Hispanic white children (6.6%), although the observed difference between non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic white children was not significant.

- Children in medium and small metropolitan areas (8.0%) and in nonmetropolitan areas (9.4%) were more likely to experience parental or guardian incarceration than children in large central metropolitan areas (5.1%) and large fringe metropolitan areas (4.5%).

Figure 2. Percentage of children aged 5–17 years who had ever lived with a parent or guardian who served time in jail or prison, by sex, age group, race and Hispanic origin, and urbanization level: United States, 2019

1Significantly different from children aged 13–17 years (p < 0.05).

2Significantly different from non-Hispanic black children (p < 0.05).

3Significantly different from children in medium and small metropolitan areas (p < 0.05).

4Significantly different from children in nonmetropolitan areas (p < 0.05).

NOTES: Ever lived with a parent or guardian who served time in jail or prison is based on responses by a knowledgeable adult, usually a parent, to the survey question, “Did (child) ever live with a parent or guardian who served time in jail or prison after (child) was born?” Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the civilian noninstitutionalized U.S. population. Access data table for Figure 2.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2019.

What percentage of children aged 5–17 years ever lived with someone who was mentally ill or severely depressed, and did this vary by sociodemographic characteristics?

- In 2019, 9.2% of children aged 5–17 years had lived with someone who was mentally ill or severely depressed (Figure 3).

- No significant sex or age differences were found in ever having lived with someone who was mentally ill or severely depressed.

- Non-Hispanic white children were more likely to have lived with someone who was mentally ill or severely depressed (11.5%) compared with non-Hispanic black children (7.3%) and Hispanic children (6.8%).

- The percentage of children who had lived with someone who was mentally ill or severely depressed increased with decreasing urbanization from 6.8% in large central metropolitan areas, to 8.1% in large fringe metropolitan areas, to 11.2% in medium and small metropolitan areas, and 12.0% among those in nonmetropolitan areas.

Figure 3. Percentage of children aged 5–17 years who had ever lived with someone who was mentally ill or severely depressed, by sex, age group, race and Hispanic origin, and urbanization level: United States, 2019

1Significantly different from non-Hispanic white children (p < 0.05).

2Significant linear trend by urbanization level (p < 0.05).

NOTES: Ever lived with someone who was mentally ill or severely depressed is based on responses by a knowledgeable adult, usually a parent, to the survey question, “Did (child) ever live with anyone who was mentally ill or severely depressed?” Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the civilian noninstitutionalized U.S. population. Access data table for Figure 3.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2019.

What percentage of children aged 5–17 years ever lived with someone with an alcohol or drug problem, and did this vary by sociodemographic characteristic?

- In 2019, 9.7% of children aged 5–17 years had lived with someone who had a problem with alcohol or drug use (Figure 4).

- No significant difference in ever having lived with someone with an alcohol or drug problem was observed between boys and girls.

- The percentage of children who had lived with someone who had a problem with alcohol or drugs increased with age, from 7.9% among those aged 5–12 years to 12.4% among those aged 13–17 years.

- Non-Hispanic black children (4.6%) and Hispanic children (7.5%) were less likely to have lived with someone with an alcohol or drug problem compared with non-Hispanic white children (12.3%). Non-Hispanic black children were also less likely to have lived with someone with an alcohol or drug problem than Hispanic children.

- The percentage of children who had lived with someone with an alcohol or drug problem increased with decreasing urbanization, from 7.3% in large central metropolitan areas, to 9.0% in large fringe metropolitan areas, to 10.7% among those in medium and small metropolitan areas and 13.7% in non-metropolitan areas.

Figure 4. Percentage of children aged 5–17 years who had ever lived with someone who had a problem with alcohol or drugs, by sex, age group, race and Hispanic origin, and urbanization level: United States, 2019

1Significantly different from children aged 13–17 years (p < 0.05).

2Significantly different from non-Hispanic white children (p < 0.05).

3Significantly different from Hispanic children (p < 0.05).

4Significant linear trend by urbanization level (p < 0.05).

NOTES: Ever lived with someone who had a problem with alcohol or drugs is based on responses by a knowledgeable adult, usually a parent, to the survey question, “Did (child) ever live with anyone who had a problem with alcohol or drugs?” Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the civilian noninstitutionalized U.S. population. Access data table for Figure 4.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2019.

Summary

In 2019, 6.8% of children aged 5–17 years were exposed to violence in their neighborhood, either as a victim or as a witness; 6.5% of children had lived with a parent or guardian who served time in jail or prison; 9.2% of children had lived with someone who was mentally ill or severely depressed; and 9.7% of children had lived with someone with an alcohol or drug problem. Children aged 13–17 years were generally more likely than those aged 5–12 years to have experienced the stressful life events examined in this report.

Non-Hispanic black children were more likely than Hispanic children to have been exposed to violence in their neighborhood and to have lived with a parent or guardian who was incarcerated. Although this pattern was also seen between non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic white children, the observed differences were not significant. Conversely, the percentage of children who had lived with someone who was mentally ill or severely depressed or had lived with someone with an alcohol or drug problem was highest for non-Hispanic white children. Disparities in stressful life events were consistently found by urbanization level. Patterns showed that children living in medium and small metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas were generally more likely to experience stressful life events compared with children living in more urban places, large fringe metropolitan and large central metropolitan areas.

Stressful life events during childhood may have a detrimental impact on physical and mental development and have both short- and long-term consequences for the child (2–9). Understanding sociodemographic disparities in stressful life events among children may inform policy for prevention and support initiatives.

Definitions

Alcohol or drug problem: Children were categorized as having ever lived with someone with an alcohol or drug problem based on an affirmative response to the question, “Did (child) ever live with anyone who had a problem with alcohol or drugs?”

Mentally ill or severely depressed: Children were categorized as having ever lived with someone who was mentally ill or severely depressed based on an affirmative response to the question, “Did (child) ever live with anyone who was mentally ill or severely depressed?”

Parental or guardian incarceration: Children were categorized as having a parent or guardian who served time in jail or prison based on an affirmative response to the question, “Did (child) ever live with a parent or guardian who served time in jail or prison after (child) was born?”

Race and Hispanic origin: Children categorized as Hispanic may be of any race or combination of races. Children categorized as non-Hispanic white or non-Hispanic black indicated one race only. Estimates for non-Hispanic children of races other than white only or black only, or of multiple races, are not shown.

Urbanization level: Categories were determined using the “2013 NCHS Urban–rural Classification Scheme for Counties” (10) and were assigned based on the county of household residence. Metropolitan (or urban) counties include large central counties (inner cities); the fringes of large counties (suburban); and medium and small counties. Nonmetropolitan (or rural) counties include micropolitan statistical areas and noncore areas, including open countryside, rural towns (populations of less than 2,500), and areas with populations of 2,500–49,999 that are not part of larger labor market areas (metropolitan areas).

Violence exposure: Children were considered to have been exposed to violence in their neighborhood based on an affirmative response to the question, “Has (child) ever been the victim of violence or witnessed violence in his/her neighborhood?”

Data source and methods

Data from the 2019 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) were used for this analysis. NHIS is a nationally representative household survey of the civilian noninstitutionalized U.S. population. It is conducted continuously throughout the year by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Interviews are conducted in respondents’ homes, but follow-ups to complete interviews may be conducted over the telephone. The sample child component of the survey, which includes the questions analyzed in this report, is completed by a knowledgeable adult, usually a parent. Questions on stressful life events are only included periodically in NHIS. For more information about NHIS, visit: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm.

Point estimates and corresponding confidence intervals for this analysis were calculated using Stata version 16 software (11) to account for the complex sample design of NHIS. Differences between percentages were evaluated using two-sided significance tests at the 0.05 level. All estimates meet NCHS standards of reliability as specified in “National Center for Health Statistics Data Presentation Standards for Proportions” (12).

About the authors

Heidi Ullmann and Julie D. Weeks are with the NCHS Division of Analysis and Epidemiology. Jennifer H. Madans is a guest researcher in the NCHS Office of the Director.

References

- Gilgoff R, Singh L, Koita K, Gentile B, and Marques SS. Adverse childhood experiences, outcomes, and interventions. Pediatri Clin North Am 67(2):259–73. 2020.

- Healthy People 2030. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

- Wright AW, Austin M, Booth C, Kliewer W. Systematic review: Exposure to community violence and physical health outcomes in youth. J Pediatr Psychol 42(4):364–78. 2017.

- Mohammad ET, Shapiro ER, Wainwright LD, Carter AS. Impacts of family and community violence exposure on child coping and mental health. J Abnorm Chil Psychol 43:203–15. 2015.

- Wildeman C, Goldman AW, Turney K. Parental incarceration and child health in the United States. Epidemiol Rev 40(1):146–56. 2018. DOI: 10.1093/epirev/mxx013.

- Turney K, Haskins AR. Parental incarceration and children’s well-being: Findings from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study. In: Eddy JM, Poehlmann-Tynan J (editors). Handbook on children with incarcerated parents. 2nd ed. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 53–64. 2019.

- Pierce M, Hope HF, Kolade A, Gellatly J, Osam CS, Perchard R, et al. Effects of parental mental illness on children’s physical health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 217(1):354–63. 2020. DOI: 10.1192/bjp.2019.216.

- Mowbray O, Jennings PF, Littleton T, Grinnell-Davis C, O’Shields J. Caregiver depression and trajectories of behavioral health among child welfare involved youth. Child Abuse Negl 79:445–53. 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.001.

- Kuppens S, Moore SC, Gross V, Lowthian E, Siddaway AP. The enduring effects of parental alcohol, tobacco, and drug use on child well-being: A multilevel meta-analysis. Dev Psychopathol 32(2):765–78. 2020. DOI: 10.1017/S0954579419000749. O’Shields J. Caregiver depression and trajectories of behavioral health among child welfare involved youth. Child Abuse Negl 79:445–53. 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.001.

- Ingram DD, Franco SJ. 2013 NCHS urban–rural classification scheme for counties. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2(166). 2014.1.

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software (Release 16) [computer software]. 2019.

- Parker JD, Talih M, Malec DJ, Beresovsky V, Carroll M, Gonzalez JF Jr, et al. National Center for Health Statistics data presentation standards for proportions. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2(175). 2017.

Suggested citation

Ullmann H, Weeks JD, Madans JH. Disparities in stressful life events among children aged 5–17 years: United States, 2019. NCHS Data Brief, no 416. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2021. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:109052.

Copyright information

All material appearing in this report is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission; citation as to source, however, is appreciated.

National Center for Health Statistics

Brian C. Moyer, Ph.D., Director

Amy M. Branum, Ph.D., Associate Director for Science

Division of Analysis and Epidemiology

Irma E. Arispe, Ph.D., Director

Kevin C. Heslin, Ph.D., Associate Director for Science