Key points

- Histoplasma mainly lives in soil in the central and eastern United States particularly areas around the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys.

- It grows especially well in material containing large amounts of bird or bat droppings.

Overview

Histoplasma is the fungus that causes histoplasmosis. It lives throughout the world. However, it's most common in North America and Central America.1

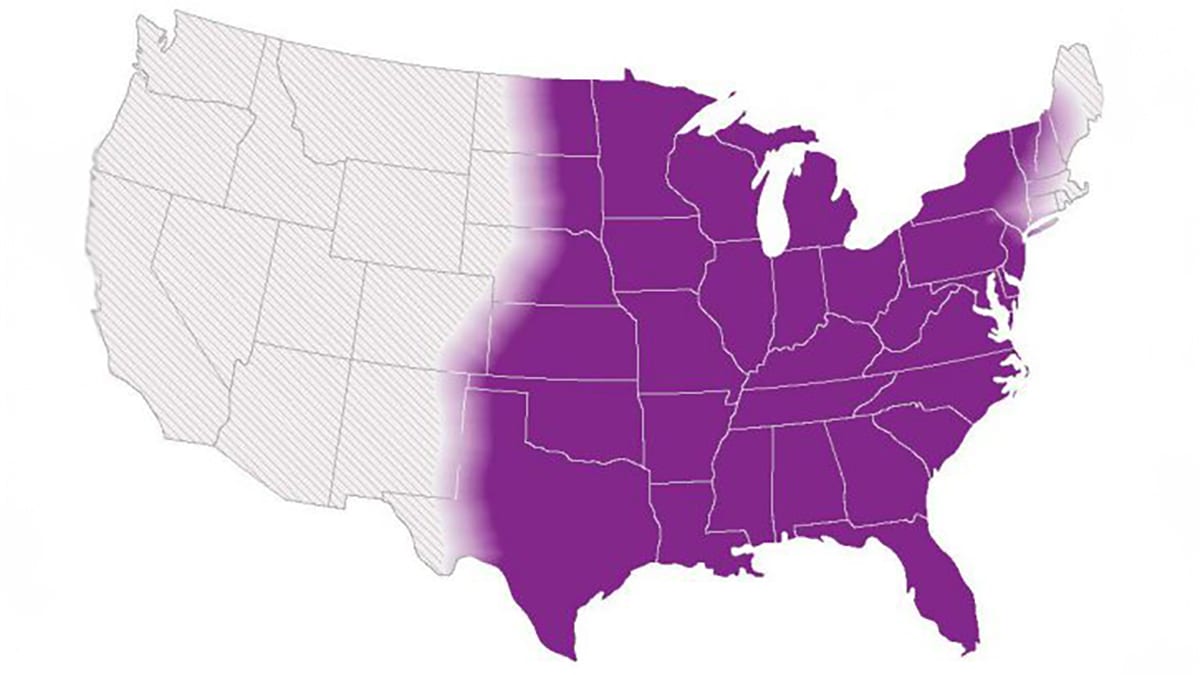

In the United States, Histoplasma mainly lives in soil in central and eastern states. For example, it lives in areas around the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys. However, it can live in other parts of the country also, especially if the environmental conditions are highly suitable. In the environment, Histoplasma is undetectable to the naked eye.

This map shows CDC's current estimate of where the fungi that cause histoplasmosis live in the environment in the United States. These fungi are spread unevenly throughout the shaded areas. Darker shading shows areas where Histoplasma is more likely to live. Diagonal shading shows the potential range of Histoplasma.

Where it lives

Histoplasma grows especially well in soil or other environmental material containing large amounts of bird or bat droppings. Bird and bat droppings act as a source for the growth of Histoplasma already present in soil.2 Fresh bird droppings on surfaces such as sidewalks and windowsills likely do not pose a risk for histoplasmosis. This is because birds themselves are rarely infected with Histoplasma. Unlike birds, bats can become infected with Histoplasma. They may also be able to excrete it in their droppings.3

A large number of birds or bats can also pose a risk for Histoplasma exposure. The types of birds typically associated with histoplasmosis outbreaks include chickens, blackbirds (starlings and grackles), pigeons, and gulls.45

Presence of birds, bats, or large accumulations of their droppings is not necessary for Histoplasma to grow. Many patients with histoplasmosis do not have such exposures.6

Histoplasma has been detected in some organic fertilizers in Latin America. More studies can help us understand whether the fungus can survive commercial fertilizer manufacturing processes.78

For any material suspected of Histoplasma contamination, the safest approach is to:

- Assume the material contains Histoplasma.

- Take exposure precautions.

- Remediate it accordingly.

Environmental Testing

Detecting Histoplasma in environmental samples can be challenging. Routine environmental sampling for Histoplasma is not recommended. However, research is needed to evaluate potential targeted testing strategies. Focused polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or culture testing can help confirm a suspected environmental source during a histoplasmosis outbreak. In outbreak settings without a clear exposure, large-scale environmental testing is unlikely to be useful.

In outbreak settings with a very clear exposure, environmental testing may not be necessary. Particularly, if the results would not change public health recommendations to prevent future cases.

Also, an environmental sample that tests negative for Histoplasma does not necessarily mean that the fungus is not present or was not present at the time the exposure occurred.

- Ashraf N, Kubat RC, Poplin V, Adenis AA, Denning DW, Wright L, McCotter O, Schwartz IS, Jackson BR, Chiller T, Bahr NC [2020]. Re-drawing the maps for endemic mycoses. Mycopathologia 185(5):843–865.

- Ajello L [1964]. Relationship of Histoplasma capsulatum to avian habitats. Public health reports 79:266–270.

- Hoff GL, Bigler WJ [1981]. The role of bats in the propagation and spread of histoplasmosis: a review. J Journal of Wildlife Diseases 17(2):191–196.

- Benedict K, Mody RK [2016]. Epidemiology of histoplasmosis outbreaks, United States, 1938-2013. Emerg Infect Dis 22(3):370–378.

- Waldman RJ, England AC, Tauxe R, Kline T, Weeks RJ, Ajello L, Kaufman L, Wentworth B, Fraser DW [1983].A winter outbreak of acute histoplasmosis in northern Michigan. Am J Epidemiol 117(1):68–75.

- Benedict K, McCracken S, Signs K, Ireland M, Amburgey V, Serrano JA, Christophe N, Gibbons-Burgener S, Hallyburton S, Warren KA, Keyser Metobo A, Odom R, Groenewold MR, Jackson BR [2020]. Enhanced surveillance for histoplasmosis—nine states, 2018–2019. Open Forum Infect Dis 7(9):ofaa343.

- Gómez LF, Torres IP, Jiménez-A MDP, McEwen JG, de Bedout C, Peláez CA, Acevedo JM, Taylor ML, Arango M [2018]. Detection of Histoplasma capsulatum in organic fertilizers by Hc100 nested polymerase chain reaction and its correlation with the physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of the samples. Am J Trop Med Hyg 98(5):1303–1312.

- Londono LFG, Leon LCP, Ochoa JGM, Rodriguez AZ, Jaramillo CAP, Ruiz JMA, Taylor ML, Arteaga MA, Alzate MDJ [2019]. Capacity of Histoplasma capsulatum to survive the composting process. Applied and Environmental Soil Science 2019.