Underutilization of Influenza Antiviral Treatment Among Children and Adolescents at Higher Risk for Influenza-Associated Complications — United States, 2023–2024

Weekly / November 14, 2024 / 73(45);1022–1029

Aaron M. Frutos, PhD1,2; Haris M. Ahmad, MPH1; Dawud Ujamaa, MS1,3; Alissa C. O’Halloran, MSPH1; Janet A. Englund, MD4; Eileen J. Klein, MD4; Danielle M. Zerr, MD4; Melanie Crossland, MPH5; Holly Staten, MPH5; Julie A. Boom, MD6,7; Leila C. Sahni, PhD6,7; Natasha B. Halasa, MD8; Laura S. Stewart, PhD8; Olla Hamdan, MPH8; Tess Stopczynski, MS8; William Schaffner, MD8; H. Keipp Talbot, MD8; Marian G. Michaels, MD9,10; John V. Williams, MD9,10; Melissa Sutton, MD11; M. Andraya Hendrick, MPH11; Mary A. Staat, MD12,13; Elizabeth P. Schlaudecker, MD12,13; Brenda L. Tesini, MD14; Christina B. Felsen, MPH14; Geoffrey A. Weinberg, MD14; Peter G. Szilagyi, MD14,15; Bridget J. Anderson, PhD16; Jemma V. Rowlands, MPH16; Murtada Khalifa, MBBS17; Marc Martinez17; Rangaraj Selvarangan, PhD18,19; Jennifer E. Schuster, MD18,19; Ruth Lynfield, MD20; Melissa McMahon, MPH20; Sue Kim, MPH21; Val Tellez Nunez, MPH21; Patricia A. Ryan, MS22; Maya L. Monroe, MPH22; Yun F. Wang, MD, PhD23; Kyle P. Openo, DrPH24,25,26; James Meek, MPH27; Kimberly Yousey-Hindes, MPH27; Nisha B. Alden, MPH28; Isaac Armistead, MD28; Suchitra Rao, MBBS29; Shua J. Chai, MD30,31; Pam Daily Kirley, MPH30; Ariana P. Toepfer, MPH32; Fatimah S. Dawood, MD32; Heidi L. Moline, MD32; Timothy M. Uyeki, MD1; Sascha Ellington, PhD1; Shikha Garg, MD1; Catherine H. Bozio, PhD1,*; Samantha M. Olson, MPH1,* (View author affiliations)

View suggested citationSummary

What is already known about this topic?

Tens of thousands of children and adolescents are hospitalized each year in the United States with influenza. Both vaccination and antiviral treatment can reduce the risk for influenza complications.

What is added by this report?

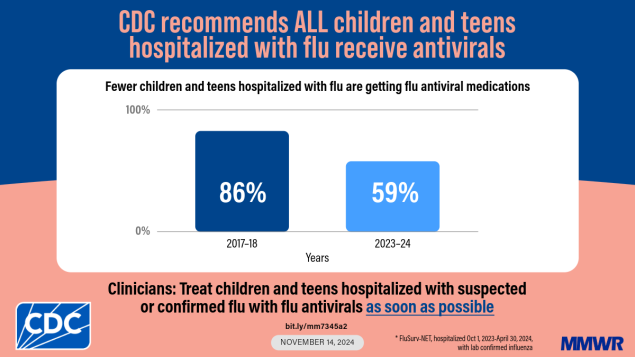

Data from two national influenza surveillance networks indicate that antiviral treatment of hospitalized children and adolescents with influenza has declined from 70%– 86% during the 2017–18 season to <60% in 2023–24. Only 30% of children and adolescents at higher risk for influenza complications were prescribed antivirals during outpatient visits.

What are the implications for public health practice?

All hospitalized children and adolescents and those at higher risk for influenza complications seen in outpatient settings with suspected influenza should receive antivirals as soon as possible to reduce the risk for influenza complications.

Altmetric:

Abstract

Annually, tens of thousands of U.S. children and adolescents are hospitalized with seasonal influenza virus infection. Both influenza vaccination and early initiation of antiviral treatment can reduce complications of influenza. Using data from two U.S. influenza surveillance networks for children and adolescents aged <18 years with medically attended, laboratory-confirmed influenza for whom antiviral treatment is recommended, the percentage who received treatment was calculated. Trends in antiviral treatment of children and adolescents hospitalized with influenza from the 2017–18 to the 2023–2024 influenza seasons were also examined. Since 2017–18, when 70%–86% of hospitalized children and adolescents with influenza received antiviral treatment, the proportion receiving treatment notably declined. Among children and adolescents with influenza during the 2023–24 season, 52%–59% of those hospitalized received antiviral treatment. During the 2023–24 season, 31% of those at higher risk for influenza complications seen in the outpatient setting in one network were prescribed antiviral treatment. These findings demonstrate that influenza antiviral treatment is underutilized among children and adolescents who could benefit from treatment. All hospitalized children and adolescents, and those at higher risk for influenza complications in the outpatient setting, should receive antiviral treatment as soon as possible for suspected or confirmed influenza.

Introduction

Annually, seasonal influenza virus infections among children and adolescents in the United States are estimated to result in millions of medical visits, tens of thousands of hospitalizations, and hundreds of deaths.† Influenza hospitalization rates among children and adolescents are highest among those aged <1 year, and rates decrease with increasing age.§ Influenza vaccination and early initiation of antiviral treatment can reduce the risk for influenza complications (1,2). Prompt antiviral treatment has also been associated with lower odds of intensive care unit (ICU) admission and death among hospitalized children and adolescents with influenza (3). Antiviral treatment is recommended as soon as possible, and treatment of any person with suspected or confirmed influenza who is hospitalized; has severe, complicated, or progressive illness; or is at higher risk for influenza complications should not await laboratory confirmation (4,5). In addition to persons with certain underlying medical conditions, children aged <5 years are considered to be at higher risk for influenza complications; the highest risk is among those aged <2 years (5).

During the 2022–23 influenza season, underutilization of antiviral treatment was observed among hospitalized children and adolescents with laboratory-confirmed influenza compared with its use during seasons before the COVID-19 pandemic (6). This report examines antiviral treatment patterns among children and adolescents with laboratory-confirmed influenza who were hospitalized and among those at higher risk for influenza complications within the outpatient setting during the 2023–24 influenza season.

Methods

Data Collection

Data were collected from two U.S. influenza surveillance networks,¶ the Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network (FluSurv-NET) and the New Vaccine Surveillance Network (NVSN). For this analysis, patients were included from both networks during October 1, 2023–April 30, 2024. FluSurv-NET is an active, population-based influenza hospitalization surveillance network that collects data on persons of all ages. A FluSurv-NET case was defined as a hospitalization of a person of any age residing in the surveillance catchment area with laboratory-confirmed influenza from a clinically ordered test.** Data were collected through review of medical records using a standardized case report form on an age-, site-, and month of admission–stratified random sample of cases from 12 sites.†† All sampled children and adolescents aged <18 years from FluSurv-NET were included in the analyses. Cases that were not sampled, cases missing influenza antiviral treatment data, cases of nosocomial influenza, and cases among pregnant persons were excluded.

NVSN is an active, population-based surveillance network that collects data from children and adolescents aged <18 years with acute respiratory illness (ARI) in outpatient (outpatient clinics, urgent care clinics, and emergency departments) and hospital settings at seven sites.§§ An NVSN case was defined as ARI¶¶ and laboratory-confirmed influenza*** from a clinically ordered test in a child or adolescent aged <18 years living in the catchment area. For NVSN, all hospitalized patients with laboratory-confirmed influenza were included, but in the outpatient setting, cases were only included if the patients were recommended to receive influenza antiviral treatment based on CDC guidance (age <5 years or having at least one underlying medical condition)††† (5). Data were collected through parent or guardian interviews with assent from the child (when applicable) and medical chart reviews. Cases with missing influenza antiviral treatment data were excluded.

Data Analysis

Influenza antiviral treatment was defined as documentation of prescription for or receipt of baloxavir, oseltamivir, peramivir, or zanamivir among persons in outpatient or inpatient hospital settings,§§§ respectively. Percentages of persons treated were calculated by dividing the number of persons treated with or prescribed antivirals by the number for whom receipt of antiviral treatment was recommended.¶¶¶ For historical context, the percentages of hospitalized children and adolescents with influenza who received antiviral treatment by age groups during October 1–April 30 from the 2017–18 through the 2022–23 seasons**** were calculated. For FluSurv-NET, unweighted counts and weighted percentages are presented to account for the complex survey design.

SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute) was used to conduct the analysis. FluSurv-NET and NVSN activities were reviewed by CDC, deemed not research, and were conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy.††††,§§§§

Results

Inpatient Influenza Antiviral Treatment Trends

During the 2017–18 season, the overall percentage of hospitalized patients aged <18 years with laboratory-confirmed influenza who were treated with antiviral medications was 70% in NVSN and 86% in FluSurv-NET (Figure). Since the 2019–20 season, the percentage of children and adolescents with influenza receiving treatment has declined and has remained lower than it was in seasons before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Characteristics of Children and Adolescents in FluSurv-NET and NVSN

During the 2023–24 influenza season, 573 influenza-associated outpatient visits and 283 influenza-associated hospitalizations in NVSN and 1,846 influenza-associated hospitalizations in FluSurv-NET were analyzed (Table 1).¶¶¶¶ Among children and adolescents with influenza-associated hospitalizations in NVSN and FluSurv-NET, the largest percentages of patients were aged 5–11 years (42% and 39%, respectively) and were non-Hispanic White persons (36% and 33%, respectively). In the outpatient setting, most children with influenza (42%) were aged 2–4 years and most (43%) were non-Hispanic Black or African American persons. Within NVSN and FluSurv-NET, 58% and 47% of hospitalized children and adolescents with influenza, respectively, did not have any underlying medical condition. Asthma or reactive airway disease was a frequently observed medical condition across networks and settings (21% in NVSN and 26% in FluSurv-NET). Among the hospitalized children and adolescents, 16% (NVSN) and 19% (FluSurv-NET) were admitted to an ICU, and 7%–13% (NVSN) and 4%–7% (FluSurv-NET) received invasive or noninvasive mechanical ventilation.

Influenza Antiviral Treatment During the 2023–24 Season

In the outpatient setting, 31% of children and adolescents who were recommended to receive antiviral treatment were prescribed antivirals (Table 2). The percentage of prescriptions was highest among children aged <6 months (49%) and lowest among those aged 2–4 years (21%); all outpatient prescriptions were for oseltamivir (Supplementary Table, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/168887).

Among children and adolescents hospitalized with influenza, 52% (NVSN) and 59% (FluSurv-NET) received antiviral treatment (Table 2). Antiviral treatment prevalence among hospitalized children and adolescents with influenza was highest among those aged <6 months (68% [NVSN]; 73% [FluSurv-NET]) and lowest among those aged 2–4 years in NVSN (43%) and 12–17 years in FluSurv-NET (49%). Nearly all treated patients received oseltamivir (99%) (Supplementary Table, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/168887); most (68% [NVSN]; 60% [FluSurv-NET]) received treatment on the day of admission, and 29% (NVSN) and 34% (FluSurv-NET) were not treated until ≥1 day after admission.

In both outpatient and inpatient settings, the percentage of children and adolescents who received antiviral treatment for laboratory-confirmed influenza rose with an increasing number of underlying medical conditions, from 28% of those with no underlying conditions to 57% among those with three or more (outpatient) and, among hospitalized patients, from 45% to 75% (NVSN), respectively, and from 55% to 77% (FluSurv-NET), respectively (Table 2). The percentage of patients with underlying medical conditions who received antiviral treatment varied by condition, network, and setting. Among those with asthma or reactive airway disease (a frequent comorbidity between networks and settings), 34% of those in outpatient settings were prescribed antivirals, and 64% (NVSN) and 62% (FluSurv-NET) of those who were hospitalized received antiviral treatment.

In children and adolescents who were hospitalized, a higher proportion of those admitted to an ICU received antiviral treatment (84% [NVSN]; 82% [FluSurv-NET]); 81% of those admitted were treated on the day of or after ICU admission. Among those who received noninvasive or invasive ventilation, 89%–94% in NVSN and 82% in FluSurv-NET received antiviral treatment.

Discussion

Seasonal influenza causes substantial disease among children and adolescents in the United States each year, and annual influenza vaccination is recommended for all persons aged ≥6 months, including those who are pregnant (to protect themselves and their infants aged <6 months through passive transplacentally transferred antibodies) (7). Antiviral treatment is an important adjunct to reduce the risk for influenza complications. Among patients with confirmed or suspected influenza, initiation of antiviral treatment is recommended as soon as possible for outpatients at higher risk for influenza complications and for all hospitalized patients (4,5). The percentage of children and adolescents with influenza-associated hospitalization who received antiviral treatment remained relatively stable from the 2017–18 season to the 2019–20 season, and subsequently decreased sharply during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although antiviral treatment has stabilized during the past two seasons, the percentages of patients treated have remained suboptimal and have not returned to prepandemic levels. During the 2023–24 influenza season, approximately one half (41%–48%) of children and adolescents with an influenza-associated hospitalization and approximately two thirds (69%) of those with an influenza-associated outpatient visit did not receive recommended antiviral treatment, highlighting missed opportunities to reduce the risk for influenza complications. This decrease in use of influenza antiviral treatment underscores the importance of increasing awareness among pediatric health care professionals about current recommendations for antiviral treatment.

Antiviral treatment is associated with improved outcomes for children and adolescents with influenza, including in-hospital survival (2,3,8). Antiviral treatment initiation shortly after influenza symptom onset provides more clinical benefit than does later treatment initiation (2,3). Among children and adolescents who are hospitalized or who are at higher risk for influenza-associated complications, there is no restriction on the timing of initiation of antiviral treatment, although starting as early as possible is recommended. Despite these recommendations, concerns about the timing of antiviral treatment relative to symptom onset and waiting for influenza test results have been noted as reasons for not prescribing antivirals among infants in the outpatient setting (9). Understanding of the reasons for nontreatment among hospitalized children and adolescents with influenza is limited, but some reasons might include concerns about adverse events (10). Increasing access to timely care, identifying potential barriers to antiviral treatment in the hospital setting, and increasing provider education concerning the benefits of timely treatment might lead to increases in antiviral treatment of persons who are recommended to receive it.

Limitations

The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, FluSurv-NET and NVSN catchment areas do not cover the entire U.S. population; characteristics of children and adolescents with medically attended and laboratory-confirmed influenza infection might not be generalizable throughout the United States. Second, antiviral treatment before hospitalization might be recorded incompletely because patients might have received treatment in the outpatient setting. Finally, the calculation of antiviral treatment timing might be imprecise because only dates and not time of admission and treatment initiation were collected.

Implications for Public Health Practice

Annual influenza vaccination provides important protection against influenza and associated complications. Among patients with confirmed or suspected influenza who are at higher risk for complications, early initiation of antiviral treatment is recommended to further reduce the risk for complications. The decrease in influenza antiviral use among children and adolescents with laboratory-confirmed influenza since the COVID-19 pandemic is concerning. Health care providers are reminded that children and adolescents with suspected or confirmed influenza who are hospitalized or have higher risk for influenza complications should receive prompt antiviral treatment.

Acknowledgments

Charisse Cummings, Angelle Naquin, Devi Sundaresan, Influenza Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC; Monet Tosch-Berneburg, Leanne Kehoe, Kirsten Lacombe, Bonnie Strelitz, Seattle Children’s Research Institute; Amanda Carter, Ryan Chatelain, Melanie Crossland, Andrea George, Emma Mendez-Edwards, Kristen Olsen, Andrea Price, Isabella Reyes, Holly Staten, Ashley Swain, Hafsa Zahid, Salt Lake County Health Department; Vasanthi Avadhanula, Pedro A. Piedra, Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine; Samar Alsabah, Justin Amarin, James Antoon, James Chappell, Annika Conlee, Katie Dyer, Emma Claire Gauthier, Haya Hayek, Gail Hughett, Karen Leib, Tiffanie Markus, Terri McMinn, Nida Mohammad, Jillian Myers, Danielle Ndi, Claudia Guevara Pulido, Collin Ragsdale, Laura Short, Andrew Spieker, Adriana Blanco Vasquez, MaKale Washington, Vanderbilt University Medical Center; Monika Johnson, Sophia Kainaroi, Samar Musa, UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh; Julie Freshwater, Denise Ingabire-Smith, Ann Salvator, Eli Shiltz, Ohio Department of Health; Heidi Arth, Eva Caudill, Miranda Howard, Caymden Hughes, Marilyn Rice, Chelsea Rohlfs, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center; Christina S. Albertin, Sophrena Bushey, Wende Fregoe, Maria Gaitan, Erin Licherdell, Christine Long, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry; Aleah Abdellatif, Grant Barney, Kerianne Engesser, Fiona Keating, Adam Rowe, New York State Department of Health; Yomei Shaw, Chad Smelser, Daniel M. Sosin, New Mexico Department of Health; Molly Bleecker, Nancy Eisenberg, Sarah Lathrop, Francesca Pacheco, Yadira Salazar-Sanchez, New Mexico Emerging Infections Program; Caroline McCahon, CDC Foundation, New Mexico Department of Health; Dinah Dosdos, Mary Moffatt, Gina Weddle, Children’s Mercy Hospital; Anna Chon, Karissa Helvig, Alli Johnson, Cynthia Kenyon, Minnesota Department of Health; Amber Brewer, Jim Collins, Justin Henderson, Shannon Johnson, Lauren Leegwater, Liz McCormick, Genevieve Palazzolo, Libby Reeg, Sarah Rojewski, Michigan Department of Health and Human Services; David Blythe, Alicia Brooks, Michael Girard, Rachel Park, Maryland Department of Health; Emily Bacon, Meghann Cantey, Rayna Ceaser, Alyssa Clausen, Trisha Deshmuhk, Emily Fawcett, Sydney Hagley-Alexander, Sabrina Hendrick, Johanna Hernandez, Asmith Joseph, Annabel Patterson, Allison Roebling, MaCayla Servais, Chandler Surell, Emma Grace Turner, Hope Wilson, Emory University School of Medicine, Georgia Emerging Infections Program, Georgia Department of Public Health, Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center; Maria Correa, Julia Desiato, Daewi Kim, Amber Maslar, Adam Misiorski, Connecticut Emerging Infections Program, Yale School of Public Health; Sharon Emmerling, Breanna Kawasaki, Madelyn Lensing, Sarah McLafferty, Jordan Surgnier, Millen Tsegaye, Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment; Brenna Hall, Joelle Nadle, Monica Napoles, Jeremy Roland, Gretchen Rothrock, California Emerging Infections Program.

Corresponding author: Aaron Frutos, AFrutos@cdc.gov.

1Influenza Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC; 2Epidemic Intelligence Service, CDC; 3General Dynamics Information Technology, Atlanta, Georgia; 4Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, Washington; 5Salt Lake County Health Department, Salt Lake City, Utah; 6Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas; 7Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, Texas; 8Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee; 9University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; 10UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; 11Public Health Division, Oregon Health Authority; 12University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio; 13Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; 14University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, New York; 15UCLA Mattel Children’s Hospital, Los Angeles, California; 16New York State Department of Health; 17New Mexico Department of Health; 18University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine, Kansas City, Missouri; 19Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, Missouri; 20Minnesota Department of Health; 21Michigan Department of Health & Human Services; 22Maryland Department of Health; 23Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Grady Health System, Atlanta, Georgia; 24Division of Infectious Diseases, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia; 25Georgia Emerging Infections Program, Georgia Department of Public Health; 26Research, Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Decatur, Georgia; 27Connecticut Emerging Infections Program, Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, Connecticut; 28Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment; 29Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, United States; 30California Emerging Infections Program, Oakland, California; 31Office of Readiness and Response, CDC; 32Coronavirus and Other Respiratory Viruses Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. Janet A. Englund reports institutional support from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Moderna, and GlaxoSmithKline; receipt of consulting fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Meissa Vaccines, Moderna, Pfizer, and Sanofi Pasteur; and receipt of honoraria from Pfizer. Natasha B. Halasa reports institutional support from Merck, and receipt of an honorarium from CSL Seqirus for service on an advisory board. Sue Kim reports grants from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. Ruth Lynfield reports receipt of a fee for serving as an Associate Editor for the American Academy of Pediatrics Redbook, which was then donated to the Minnesota Department of Health. Leila C. Sahni reports travel support from the Gates Foundation. Elizabeth P. Schlaudecker reports institutional support from Pfizer; receipt of an honorarium from Sanofi Pasteur for service on an advisory board; and travel support for meeting attendance from the World Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases, the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, and Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society; uncompensated membership of a National Institutes of Health Data Safety Monitoring Board; and membership on the board of the World Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases. Jennifer E. Schuster reports institutional support from the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration and the State of Missouri; receipt of a consulting fee from the Association of Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology and a speaking honorarium from the Missouri Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics; membership on the Association of American medical Colleges advisory board. Rangaraj Selvarangan reports institutional support from Abbot, Cepheid, Biomerieux, Hologic, BioRad, Qiagen, Diasorin, and Merck; receipt of payment from GlaxoSmithKline, Baebies Biomerieux and Abbot; and travel support from Biomerieux and Hologic. Mary A. Staat reports institutional support from the National Institutes of Health, Cepheid, and Merck; royalties from UpToDate; and consulting fees from Merck. Dawud Ujamaa reports consulting fees from Goldbelt, Inc. Geoffrey A. Weinberg reports institutional support from the New York State Department of Health; consulting fees from the New York State Department of Health, Inhalon Biopharma, and ReViral; honorarium from Merck; and participation on an Emory University Data Safety Monitoring Board. No other potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

* These senior authors contributed equally to this report.

† https://www.cdc.gov/flu-burden/php/data-vis/index.html

§ https://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/FluView/FluHospRates.html

¶ https://www.cdc.gov/fluview/overview/influenza-hospitalization-surveillance.html; https://www.cdc.gov/nvsn/php/about/index.html

** Defined as receipt of a positive test result from a viral culture, direct or indirect fluorescent antibody staining, rapid antigen test, molecular assay, or evidence of a positive influenza test result in a clinical note within 14 days before or during hospitalization.

†† Patients in FluSurv-NET lived in catchment area counties from the following states: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Tennessee, and Utah.

§§ Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee; University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry-Medical Center/UR-Golisano Children’s Hospital, Rochester, New York; Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, Texas; Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, Washington; Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, Missouri; Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

¶¶ ARI is defined as at least one of the following within 10 days of the medical encounter: fever, cough, earache, nasal congestion, runny nose, sore throat, wheezing, shortness of breath or rapid shallow breathing, apnea, apparent life-threatening event, or briefly resolved unexplained event.

*** Defined as receipt of a positive test result from a rapid antigen or polymerase chain reaction test or a molecular assay.

††† Asthma or reactive airway disease, chronic lung disease, cancer, organ transplant, chronic metabolic disease, blood disorders, cardiovascular disease, neurologic disorders, immunocompromised, renal disease, liver disease, or obesity among children and adolescents aged ≥2 years).

§§§ For FluSurv-NET, this could be up to 2 weeks before or at any time during hospitalization.

¶¶¶ Includes all persons with influenza who were hospitalized or, in the outpatient setting, those aged <5 years, or with illness in one of the following medical condition categories: asthma or reactive airway disease, chronic lung disease, cancer, organ transplant, chronic metabolic disease, blood disorders, cardiovascular disease, neurologic disorders, immunocompromised, renal disease, liver disease, or obesity (among children aged ≥2 years).

**** The 2020–21 influenza season was excluded because of minimal influenza activity.

†††† 45 C.F.R. part 46.102(l)(2), 21 C.F.R. part 56; 42 U.S.C. Sect. 241(d); 5 U.S.C. Sect. 552a; 44 U.S.C. Sect. 3501 et seq.

§§§§ FluSurv-NET and NVSN sites obtained human subjects and ethics approval from their respective state health departments, academic partners, or participating hospital institutional review boards.

¶¶¶¶ In FluSurv-NET, a total of 1,026 cases were excluded: 954 were not sampled, 14 sampled cases were missing antiviral use data, 50 sampled cases were considered nosocomial (positive influenza test result >3 days after hospital admission), and eight persons with sampled cases were pregnant.

References

- Olson SM, Newhams MM, Halasa NB, et al.; Pediatric Intensive Care Influenza Investigators. Vaccine effectiveness against life-threatening influenza illness in US children. Clin Infect Dis 2022;75:230–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab931 PMID:35024795

- Melosh RE, Martin ET, Heikkinen T, Brooks WA, Whitley RJ, Monto AS. Efficacy and safety of oseltamivir in children: systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis 2018;66:1492–500. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix1040 PMID:29186364

- Walsh PS, Schnadower D, Zhang Y, Ramgopal S, Shah SS, Wilson PM. JAMA Pediatr 2022;176:e223261. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.3261 PMID:36121673

- Uyeki TM, Bernstein HH, Bradley JS, et al. Clin Infect Dis 2019;68:895–902. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy874 PMID:30834445

- CDC. Influenza antiviral medications: summary for clinicians. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2024 Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/hcp/antivirals/summary-clinicians.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm.

- White EB, O’Halloran A, Sundaresan D, et al. High influenza incidence and disease severity among children and adolescents aged <18 years—United States, 2022–23 season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023;72:1108–14. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7241a2 PMID:37824430

- Grohskopf LA, Ferdinands JM, Blanton LH, Broder KR, Loehr J. MMWR Recomm Rep 2024;73(No. RR-5):1–25. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr7305a1 PMID:39197095

- Campbell AP, Tokars JI, Reynolds S, et al. Pediatrics 2021;148:e2021050417. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-050417 PMID:34470815

- Zaheer HA, Moehling Geffel K, Chamseddine S, et al. Factors associated with nonprescription of oseltamivir for infant influenza over 9 seasons. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2024;13:466–74. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpids/piae075 PMID:39082694

- Stockmann C, Byington CL, Pavia AT, et al. Limited and variable use of antivirals for children hospitalized with influenza. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171:299–301. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3484 PMID:28114638

FIGURE. Antiviral treatment among children and adolescents aged <18 years hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza, overall and by age group — two multistate surveillance networks,* United States, 2017–18 to 2023–24 influenza seasons†,§

FIGURE. Antiviral treatment among children and adolescents aged <18 years hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza, overall and by age group — two multistate surveillance networks,* United States, 2017–18 to 2023–24 influenza seasons†,§

Abbreviations: FluSurv-NET = Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network; NVSN = New Vaccine Surveillance Network.

* Data presented overall for NVSN, and overall and by age groups for FluSurv-NET. Unless indicated, data included are from FluSurv-NET.

† Clinical data were available on sampled FluSurv-NET cases for persons admitted during October 1–April 30 each season. This includes 8,907 children and adolescents in total, with 1,827 from 2017–18; 1,797 from 2018–19; 1,864 from 2019–20; 337 from 2021–22; 1,236 from 2022–23; and 1,846 from 2023–24. The 2020–21 influenza season was excluded because of minimal influenza activity.

§ Clinical influenza positive inpatient data were available from children and adolescents in NVSN admitted from October 1 through April 30 each season. This includes 1,175 children and adolescents in total, with 186 from 2017–18; 169 from 2018–19; 268 from 2019–20; 65 from 2021–22; 204 from 2022–23; and 283 from 2023–24. The 2020–21 influenza season was excluded because of minimal influenza activity.

Abbreviations: ARI = acute respiratory illness; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; FluSurv-NET = Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network; ICU = intensive care unit; NVSN = New Vaccine Surveillance Network.

* Weighted percentages are calculated using sampling weights for FluSurv-NET.

† Including outpatient clinics, urgent care clinics, and emergency departments. Only children and adolescents recommended to receive antiviral medication in the outpatient setting are included (specifically those aged <5 years or any child or adolescent with illness in one of the following medical condition categories: asthma or reactive airway disease, chronic lung disease, cancer, organ transplant, chronic metabolic disease, blood disorders, cardiovascular disease, neurologic disorders, immunocompromised, renal disease, liver disease, or obesity [among children aged ≥2 years]).

§ Persons of Hispanic or Latino (Hispanic) origin might be of any race but are categorized as Hispanic; all racial groups are non-Hispanic.

¶ For FluSurv-NET, ARI includes any of the following: fever, cough, nasal congestion, chest congestion, sore throat, hemoptysis, wheezing, apnea, cyanosis, difficulty breathing, nasal flaring, grunting, retractions, stridor, or shortness of breath. ARI at admission is part of the inclusion criteria for NVSN.

** Calculated as the number of conditions across categories including asthma or reactive airway disease, chronic lung disease, cancer, organ transplant, chronic metabolic disease, blood disorders, cardiovascular disease, neurologic disorders, immunocompromised, renal disease, liver disease, obesity (among children and adolescents aged ≥2 years), and prematurity (among those aged <24 months).

†† Bilevel positive airway pressure or continuous positive airway pressure.

Abbreviations: ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; FluSurv-NET = Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network; ICU = intensive care unit; NVSN = New Vaccine Surveillance Network.

* Weighted percentages calculated using sampling weights for FluSurv-NET.

† Including outpatient clinics, urgent care clinics, and emergency departments. Only children and adolescents recommended to receive antiviral medication in the outpatient setting are included (specifically those aged <5 years or any child or adolescent with an illness in one of the following medical condition categories: asthma or reactive airway disease, chronic lung disease, cancer, organ transplant, chronic metabolic disease, blood disorders, cardiovascular disease, neurologic disorders, immunocompromised, renal disease, liver disease, or obesity [among children and adolescents aged ≥2 years]).

§ Persons of Hispanic or Latino (Hispanic) origin might be of any race but are categorized as Hispanic; all racial groups are non-Hispanic.

¶ Includes the following medical condition categories: asthma or reactive airway disease, chronic lung disease, cancer, organ transplant, chronic metabolic disease, blood disorders, cardiovascular disease, neurologic disorders, immunocompromised, renal disease, liver disease, obesity (among children aged ≥2 years), and prematurity (among those aged <24 months).

** Calculated as the number of conditions across categories including asthma or reactive airway disease, chronic lung disease, cancer, organ transplant, chronic metabolic disease, blood disorders, cardiovascular disease, neurologic disorders, immunocompromised, renal disease, liver disease, obesity (among children and adolescents aged ≥2 years), and prematurity (among those aged <24 months).

†† Bilevel positive airway pressure or continuous positive airway pressure.

Suggested citation for this article: Frutos AM, Ahmad HM, Ujamaa D, et al. Underutilization of Influenza Antiviral Treatment Among Children and Adolescents at Higher Risk for Influenza-Associated Complications — United States, 2023–2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2024;73:1022–1029. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7345a2.

MMWR and Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report are service marks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services.

References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are

provided as a service to MMWR readers and do not constitute or imply

endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content

of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed in MMWR were current as of

the date of publication.

All HTML versions of MMWR articles are generated from final proofs through an automated process. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables.

Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.