Surveillance of Waterborne Disease Outbreaks Associated with Drinking Water — United States, 2015–2020

Surveillance Summaries / March 14, 2024 / 73(1);1–23

Jasen M. Kunz, MPH1; Hannah Lawinger, MPH1; Shanna Miko, DNP1; Megan Gerdes, MPH2; Muhammad Thuneibat, MPH2; Elizabeth Hannapel, MPH3; Virginia A. Roberts, MSPH1 (View author affiliations)

View suggested citationAltmetric:

Abstract

Problem/Condition: Public health agencies in U.S. states, territories, and freely associated states investigate and voluntarily report waterborne disease outbreaks to CDC through the National Outbreak Reporting System (NORS). This report summarizes NORS drinking water outbreak epidemiologic, laboratory, and environmental data, including data for both public and private drinking water systems. The report presents outbreak-contributing factors (i.e., practices and factors that lead to outbreaks) and, for the first time, categorizes outbreaks as biofilm pathogen or enteric illness associated.

Period Covered: 2015–2020.

Description of System: CDC launched NORS in 2009 as a web-based platform into which public health departments voluntarily enter outbreak information. Through NORS, CDC collects reports of enteric disease outbreaks caused by bacterial, viral, parasitic, chemical, toxin, and unknown agents as well as foodborne and waterborne outbreaks of nonenteric disease. Data provided by NORS users, when known, for drinking water outbreaks include 1) the number of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths; 2) the etiologic agent (confirmed or suspected); 3) the implicated type of water system (e.g., community or individual or private); 4) the setting of exposure (e.g., hospital or health care facility; hotel, motel, lodge, or inn; or private residence); and 5) relevant epidemiologic and environmental data needed to describe the outbreak and characterize contributing factors.

Results: During 2015–2020, public health officials from 28 states voluntarily reported 214 outbreaks associated with drinking water and 454 contributing factor types. The reported etiologies included 187 (87%) biofilm associated, 24 (11%) enteric illness associated, two (1%) unknown, and one (<1%) chemical or toxin. A total of 172 (80%) outbreaks were linked to water from public water systems, 22 (10%) to unknown water systems, 17 (8%) to individual or private systems, and two (0.9%) to other systems; one (0.5%) system type was not reported. Drinking water-associated outbreaks resulted in at least 2,140 cases of illness, 563 hospitalizations (26% of cases), and 88 deaths (4% of cases). Individual or private water systems were implicated in 944 (43%) cases, 52 (9%) hospitalizations, and 14 (16%) deaths.

Enteric illness-associated pathogens were implicated in 1,299 (61%) of all illnesses, and 10 (2%) hospitalizations. No deaths were reported. Among these illnesses, three pathogens (norovirus, Shigella, and Campylobacter) or multiple etiologies including these pathogens resulted in 1,225 (94%) cases. The drinking water source was identified most often (n = 34; 7%) as the contributing factor in enteric disease outbreaks. When water source (e.g., groundwater) was known (n = 14), wells were identified in 13 (93%) of enteric disease outbreaks.

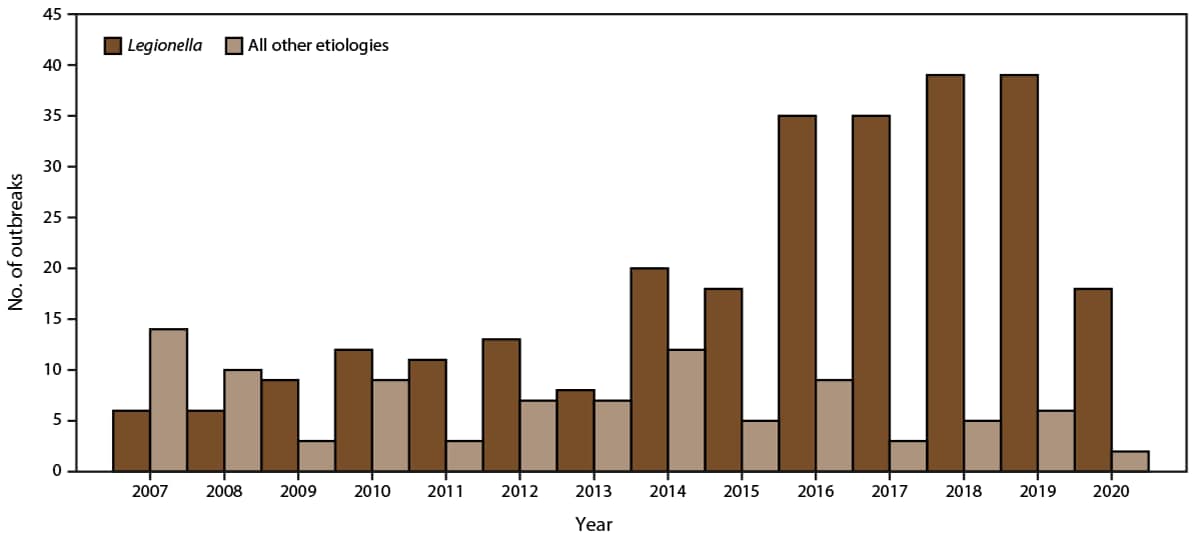

Most biofilm-related outbreak reports implicated Legionella (n = 184; 98%); two nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) (1%) and one Pseudomonas (0.5%) outbreaks comprised the remaining. Legionella-associated outbreaks generally increased over the study period (14 in 2015, 31 in 2016, 30 in 2017, 34 in 2018, 33 in 2019, and 18 in 2020). The Legionella-associated outbreaks resulted in 786 (37%) of all illnesses, 544 (97%) hospitalizations, and 86 (98%) of all deaths. Legionella also was the outbreak etiology in 160 (92%) public water system outbreaks. Outbreak reports cited the premise or point of use location most frequently as the contributing factor for Legionella and other biofilm-associated pathogen outbreaks (n = 287; 63%). Legionella was reported to NORS in 2015 and 2019 as the cause of three outbreaks in private residences (2).

Interpretation: The observed range of biofilm and enteric drinking water pathogen contributing factors illustrate the complexity of drinking water-related disease prevention and the need for water source-to-tap prevention strategies. Legionella-associated outbreaks have increased in number over time and were the leading cause of reported drinking water outbreaks, including hospitalizations and deaths. Enteric illness outbreaks primarily linked to wells represented approximately half the cases during this reporting period. This report enhances CDC efforts to estimate the U.S. illness and health care cost impacts of waterborne disease, which revealed that biofilm-related pathogens, NTM, and Legionella have emerged as the predominant causes of hospitalizations and deaths from waterborne- and drinking water-associated disease.

Public Health Action: Public health departments, regulators, and drinking water partners can use these findings to identify emerging waterborne disease threats, guide outbreak response and prevention programs, and support drinking water regulatory efforts.

Introduction

Access to and provision of safe water in the United States is critical to protecting public health (1). Disruptions to water service caused by drinking water contamination can negatively impact public health and erode public trust in drinking water quality. Each year in the United States, waterborne pathogens cause an estimated 7.15 million illnesses, 118,000 hospitalizations, and 6,630 deaths, resulting in $3.33 billion in direct health care costs (2). Drinking water exposures are associated with 40% of hospitalizations and 50% of deaths and are primarily linked with biofilm pathogens such as Legionella and nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), costing the United States $1.39 billion annually (3). Biofilms are microbial communities that attach to moist surfaces (e.g., water pipes) and provide protection and nutrients for many different types of pathogens, including Legionella and NTM (3,4). Biofilm can grow when water becomes stagnant or disinfectant residuals are depleted, resulting in pathogen growth (3). Furthermore, biofilm pathogens are difficult to control because of their resistance to water treatment processes (e.g., disinfection) (3). Exposure to biofilm pathogens can occur through contact with, ingestion of, or aerosol inhalation of contaminated water from different fixtures (e.g., showerheads) and devices (e.g., humidifiers) (3).

Public health surveillance and other prevention programs support water treatment, regulations, and building or household water management practices in reducing waterborne diseases. Public health agencies in the United States, District of Columbia, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Marshall Islands, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Puerto Rico, and U.S. Virgin Islands investigate and can voluntarily report waterborne disease outbreaks to CDC through the National Outbreak Reporting System (NORS) (https://www.cdc.gov/nors/about.html).

This report summarizes data on drinking water-associated outbreaks reported to NORS during 2015–2020. Drinking water, also called tap or potable water, includes water collected, treated, stored, or distributed in public and individual water systems or commercially bottled and distributed for individual use. Drinking water is used for consumption and other domestic uses (e.g., drinking, bathing, showering, handwashing, food preparation, dishwashing, and maintaining oral hygiene). This report summarizes outbreak contributing factors (i.e., practices and factors that lead to outbreaks) and, for the first time, categorizes outbreaks as biofilm pathogen or enteric illness associated (5–9). Public health departments, regulators, and drinking water partners can use the findings in this report to guide outbreak response and prevention programs and drinking water regulatory efforts.

Methods

Data Source

CDC’s Waterborne Disease and Outbreak Surveillance System began in 1971, with reporting via paper forms through 2008. CDC launched NORS (https://www.cdc.gov/nors/about.html) in 2009 as a web-based platform for state, local, and territorial health departments to enter reports of all waterborne and foodborne disease outbreaks and all enteric disease outbreaks resulting from transmission by contact with contaminated environmental sources, infected persons or animals, or unknown modes. Most outbreaks in the United States are investigated by state, local, and territorial health departments. Outbreak information is then voluntarily reported to CDC by the public health agency that conducted the investigation. CDC might be involved in outbreak investigations that involve more than one state, are particularly large, or for which the state or local health department requests assistance.

Waterborne Outbreak Definitions and Specifications

NORS users enter a confirmed or suspected etiology, if known, including species, serotype, or other characteristics. Etiologies for reported drinking water outbreaks in NORS can include infectious (e.g., Campylobacter, Cryptosporidium, Giardia, and Legionella) and noninfectious (e.g., copper and nonbacterial toxins) agents.

For NORS reporting, an outbreak is defined as two or more cases of similar illness associated with a common exposure. Outbreaks reported to NORS must include two or more cases linked epidemiologically by time, location of water exposure, and illness characteristics; the epidemiologic evidence must implicate water exposure as the probable source of illness for an event to be defined as a waterborne disease outbreak. Premise plumbing refers to a building’s hot- and cold-water piping system. For this analysis, the premise plumbing pathogens NTM, Pseudomonas, and Legionella were defined as biofilm-associated pathogens (2,10). In addition, consistent with the literature, Campylobacter, Cryptosporidium, Giardia, norovirus, and Shigella were defined as infectious enteric pathogens (2,11). Outbreaks of unknown etiology and noninfectious illness (e.g., chemical or toxin), were classified in their own categories.

Community and noncommunity water systems are defined by the Environmental Protection Agency as public water systems that have ≥15 service connections or serve an average of ≥25 residents for ≥60 days per year. A community water system serves year-round residents of a community, subdivision, or mobile home park. A noncommunity water system serves an institution, industry, camp, park, hotel, or business and can be nontransient or transient. Nontransient systems serve ≥25 of the same persons for ≥6 months of the year but not year-round (e.g., factories and schools), whereas transient systems provide water to places in which persons do not remain for long periods (e.g., restaurants, highway rest stations, and parks). Individual water systems are small systems not owned or operated by a water utility that have <15 connections or serve <25 persons (12).

NORS encourages users to indicate, when known, the water source and water source description for drinking water outbreaks. Water sources for drinking water outbreaks listed in NORS include groundwater, surface water, groundwater under the influence of surface water, other, and unknown. Water source descriptions listed in NORS include lake or reservoir, ocean, pond, river or stream, spring, well, other, and unknown.

NORS defines water treatment as the treatment usually provided before water use or water consumption, regardless of whether these treatments were operating correctly at or just before the time of the outbreak. Possible water treatment methods listed for the drinking water systems in NORS include disinfection, filtration, coagulation, flocculation, no treatment, other, and unknown.

NORS includes options to indicate where the exposure to water occurred. Settings of exposure for drinking water outbreaks listed in NORS include apartment or condominium; assisted living or rehabilitation facility, camp or cabin setting; community or municipality; hospital or health care facility; hotel, motel, lodge, or inn; long-term care facility; mobile home park; private residence; resort, restaurant or cafeteria; school, college, or university; subdivision or neighborhood; and several other types of settings.

NORS encourages users to indicate which, if any, contributing factors led to the outbreak. Users can select contributing factors from a list related to drinking water outbreaks or enter their own factors. Contributing factors for this reporting period included documented or observed (if information is gathered during document reviews, direct observations or interviews) or suspected (if factors that might have occurred but for which no documentation or observable evidence is available). Contributing factors were categorized by factor types including source (water quality was affected by a problem occurring with the source water), treatment (water quality was affected by a problem occurring with water treatment), distribution (water quality was affected by a problem within the distribution system before entry into a building or house), and premise or point of use (water quality was affected by a problem after the water meter or outside the jurisdiction of the public water utility).

Data Analysis

CDC analyzed outbreaks reported in NORS as of October 18, 2022, (via CDC 52.12 Form) to provide information about drinking water-associated waterborne disease outbreaks in the United States in which the first illness occurred during 2015–2020. For each outbreak, NORS users provided data (when known) about: 1) number of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths; 2) etiologic agent (confirmed or suspected); 3) implicated water system and treatment method; 4) setting of exposure (e.g., hospital or health care facility; hotel, motel, lodge, or inn; and private residence); and 5) relevant epidemiologic and environmental data needed to understand the outbreak occurrences and contributing factor classification.

CDC calculated descriptive statistics on characteristics of reported drinking water outbreaks. Data cleaning, management, and analysis were conducted using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute) and Microsoft Excel for Microsoft 365 Microsoft Office (version 2022; Microsoft Corporation). The analysis included both confirmed and suspected etiologies. Outbreaks with multiple etiologies were classified and analyzed as one outbreak.

Results

All Outbreaks

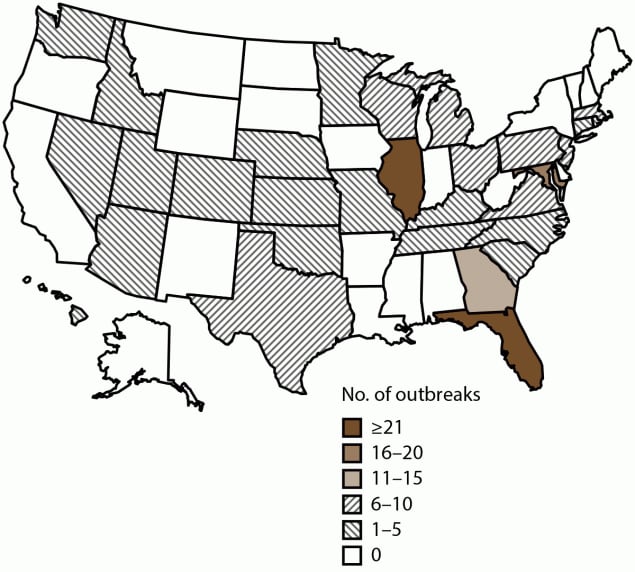

Public health officials from 28 states reported 214 outbreaks associated with drinking water during the surveillance period (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6) (Figure 1). Reported outbreaks included 187 biofilm-associated, 24 enteric illness-associated, and three other (two unknown and one chemical or toxin) etiologies (Table 7) (Figure 2). Outbreaks resulted in at least 2,140 cases of illness, 563 hospitalizations (26% of cases), and 88 deaths (4% of cases). At least one etiologic agent was identified in 212 (99%) outbreaks (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6).

Water Systems, Sources, and Contributing Factors

Community or noncommunity water systems (i.e., public) were linked with 172 (80%) outbreaks, 22 (10%) outbreaks with unknown water systems, 17 (8%) with individual or private systems (i.e., unregulated), and two (0.9%) with other systems; one system type (0.5%) was not reported. Water from individual or private water systems was implicated in 944 (44%) cases, 52 (9%) hospitalizations, and 14 (16%) deaths (Tables 1–6). Drinking water systems with groundwater sources accounted for 82 (38%) outbreaks, surface water sources accounted for 57 (27%) outbreaks, and unknown water sources accounted for 61 (29%) outbreaks (Table 7). A total of 454 contributing factors (practices and factors that led to the outbreak) were reported for 144 (67%) outbreaks (Tables 8 and 9). A total of 393 contributing factors were reported for biofilm-associated outbreaks and 61 for enteric illness-associated outbreaks.

Enteric Illness-Associated Etiologies

Outbreaks of enteric illness included 24 (11%) reports implicating Campylobacter (n = 2; 1%), Cryptosporidium (n = 2; 1%), Escherichia coli (n = 1; 0.5%), Giardia (n = 3; 1%), norovirus (n = 7; 3%), Shigella (n = 4; 2%), and multiple etiologies (n = 5; 2%) (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6). The enteric illness outbreaks resulted in 1,299 (61%) cases, 10 (2%) hospitalizations, and no deaths. Seventeen outbreaks were linked to norovirus, Shigella, Campylobacter, or multiple etiology outbreaks including these three pathogens and were implicated in 1,225 (57%) cases.

Water System and Water Source

The largest number of cases reported for a single outbreak was 693 (32%). This outbreak was linked to water from an individual or private water system that was contaminated with norovirus and enteropathogenic E. coli (Table 4). When water source (e.g., groundwater) was known (n = 14), wells were identified in 13 (93%) of enteric illness outbreaks, regardless of water system (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6).

Contributing Factors

A total of 61 (13%) contributing factors were reported for enteric illness outbreaks (Table 9). Water source was the most cited contributing factor type for enteric illness outbreaks, described by 34 (56%) individual contributing factors. Contamination through limestone or fissured rock (e.g., karst) (n = 7; 11%), improper construction or location of a well or spring (n = 7; 11%), and flooding or heavy rains (n = 5; 8%) were the most reported source water contributing factors for enteric illness outbreaks. No disinfection (n = 9, 15%), no filtration (n = 5, 8%), and chronically inadequate disinfection (n = 2; 3%) were the most frequently reported treatment contributing factors for enteric disease outbreaks (Table 9).

Biofilm-Associated Etiologies

Biofilm-associated outbreaks comprised 184 Legionella (86%), two NTM (1%), and one Pseudomonas (0.5%) outbreaks (Table 7). Legionella-associated outbreaks generally increased in number over the study period (14 in 2015, 31 in 2016, 30 in 2017, 34 in 2018, 33 in 2019, and 18 in 2020). The Legionella outbreaks resulted in 786 (37%) cases (Table 7), 544 (97%) hospitalizations, and 86 (98%) deaths (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6).

Water System

Legionella was the most implicated etiology in public water system outbreaks, associated with 160 (92%) outbreaks, 666 (60%) cases, 462 (97%) hospitalizations, and 68 (97%) deaths related to community and noncommunity water systems (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6). Individual or private water system outbreaks associated with Legionella resulted in 71 (8%) cases, 48 (92%) hospitalizations, and 14 (100%) deaths.

Contributing Factors

A total of 393 (87%) contributing factors were reported for Legionella and other biofilm pathogen-associated outbreaks (Table 8). Premise or point of use was the most cited contributing factor type for all biofilm-associated pathogen outbreaks and was linked with 287 (73%) individual contributing factors. The most reported premise or point of use contributing factors were Legionella species in water system (n = 67; 17%), Legionella growth-promoting water temperatures and permissive chlorine levels within the building potable water system (n = 35; 9%), water temperature ≥86°F (≥30°C) (n = 28; 7%), and aging plumbing components (e.g., pipes, tanks, and valves) (n = 27; 7%) (Table 8).

Water Treatment and Water Treatment Methods

A total of 183 (86%) outbreak reports contained information about water treatment. Among all outbreaks, disinfection was the reported water treatment for 116 (54%) drinking water systems, unknown water treatment for 49 (23%) drinking water systems, and no water treatment for 17 (8%) drinking water systems (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6). Seventy-nine outbreak reports (37%) indicated that chlorine was the water treatment method (e.g., description), 99 (46%) reported unknown or no treatment description, and 12 (6%) reported chloramine as the treatment description.

Settings

Hospital or health care facility, long-term care facility, and assisted living or rehabilitation facility (i.e., health care) were identified as the exposure settings in 113 (53%) outbreaks, 456 (21%) cases, 372 (66%) hospitalizations, and 75 (87%) deaths (Figure 3). Furthermore, in the health care facility setting, Legionella was implicated in 111 (52%) outbreaks, 444 (21%) cases, 364 (65%) hospitalizations, and 73 (85%) deaths. Hotels, motels, lodges, or inns were implicated in 35 (16%) outbreaks, 225 (11%) cases, 85 (15%) hospitalizations, and three (3%) deaths, all of which were caused by Legionella (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6). Finally, Legionella was reported to NORS in 2015 and 2019 as the cause of three outbreaks in private residences resulting in seven (0.3%) cases, four (0.7%) hospitalizations, and no deaths (Tables 1 and 4) (Figure 3) (2).

Discussion

Drinking water treatment, regulations, and public health programs reduce the risk for exposure to drinking water pathogens, chemicals, and toxins in the United States. Recent estimates of waterborne infectious illness and health care cost effects in the United States have revealed that biofilm-associated pathogens, Legionella and NTM, have emerged as the predominant causes of hospitalizations and deaths from waterborne and drinking water-related disease (3). However, NTM infections are not nationally notifiable diseases and cases and outbreaks might remain undetected (3). Furthermore, during 2015–2020, Legionella-associated outbreaks continued to increase and were the leading cause of nationally reported drinking water-related outbreaks, hospitalizations, and deaths. This trend was primarily influenced by the increasing number and proportion of Legionella-associated outbreaks linked with community and noncommunity water systems (Figures 4 and 5) (6). In addition, Legionella was implicated in all lodging and nearly all (n = 111; 98%) health care-associated biofilm-related outbreaks. Furthermore, Legionella-associated outbreaks in health care settings resulted in approximately two thirds (n = 364; 65%) of hospitalizations and three fourths (n = 73; 85%) of deaths reported during this period. These findings highlight the severity of Legionella infection in the health care setting (13). Legionella also was reported for the first time to NORS as the cause of three outbreaks in private residences. Legionella-associated outbreaks in private residences is an emerging concern. Additional data are needed to better characterize the role of premise plumbing systems in private homes as a potential source of exposure to Legionella and Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks (14). These outbreaks illustrate the importance of effective regulations, water management programs, and public health prevention programs that include communications to reduce the risk for biofilm pathogen growth and spread in public drinking water systems, building water systems, and private homes (4,15,16).

Enteric illness outbreaks represent 11% (n = 24) of the outbreaks, approximately 60% of the cases during this reporting period. Settings varied widely, including mobile home parks, lodging, amusement parks, farms, camps, and private residences. Enteric illness outbreaks associated with norovirus, Shigella, Campylobacter, or multiple etiology outbreaks were primarily associated with individual or private and community water systems. One outbreak of norovirus and enteropathogenic E. coli that resulted in 693 (32%) cases occurred in an amusement park setting because of an overly pumped, improperly constructed well with chronically inadequate disinfection. Wells also were identified as the water source when reported, regardless of water system type (i.e., community or individual or private) in nearly all (n = 13; 93%) enteric illness drinking water outbreaks. No disinfection was reported in nearly 75% (n = 11) of these outbreaks when water treatment was known, underscoring the importance of proper well construction, location (i.e., under the influence of surface water or proximity to wastewater disposal system), operation, and maintenance (17–20).

Understanding and communicating contributing factors related to waterborne outbreaks can lead to improved outbreak prevention, response, and communication practices (21,22). Most drinking water-associated outbreaks have multiple contributing factors, and the most frequently reported types vary between Legionella-associated and enteric illness outbreaks. For example, premise plumbing or point of use is the most cited contributing factor type for Legionella-associated outbreaks, whereas water source is most cited for enteric illness outbreaks. Furthermore, most Legionella-associated outbreak investigations are prompted by cases associated with premise plumbing systems. As a result, premise plumbing contributing factors (e.g., inadequate disinfection or Legionella-promoting water temperatures) are frequently identified. Determining the potential role of other upstream contributing factor types (e.g., water distribution systems) might be difficult. Whereas enteric illness investigations outbreaks frequently result from upstream contributing factors (e.g., disinfection failure or well or groundwater contamination) and can result in many cases of illness. The observed range of biofilm and enteric drinking water pathogen contributing factors illustrates the complexity of drinking water-related disease prevention and the need for water source-to-tap prevention strategies (16,20,23).

Limitations

The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations. First, reporting to NORS is voluntary, and surveillance, outbreak investigation, and reporting capabilities vary by jurisdiction. Outbreak surveillance data might not represent the characteristics of all outbreaks and likely underestimate the actual occurrence of outbreaks. Therefore, NORS data should not be used to estimate the actual number of outbreaks. Reports of investigated outbreaks vary, and data are limited to what is available and reported by jurisdictions. Second, Legionella-associated outbreak investigations can continue for years, with new cases of illness occurring after extended periods; jurisdictions might not report to NORS until conclusion of the investigation. Third, the COVID-19 pandemic might have affected jurisdictions’ ability to report waterborne disease outbreaks during 2019–2020. Finally, contributing factors were not available for 70 (33%) drinking water-associated outbreaks, and water treatment was unknown for 49 (23%) drinking water-associated outbreaks. Furthermore, certain Legionella and biofilm-associated pathogen outbreak contributing factors that were self-reported as distribution factor types by users align more closely with premise or point-of-use factor types, possibly resulting in misclassification bias. Legionella species in water systems was frequently reported as a contributing factor and does not provide insight into factors that led to Legionella growth and spread within the water system.

Future Directions

NORS was updated substantially (CDC 52.14 Form; https://www.cdc.gov/nors/forms.html) in January 2023. The update streamlined the environmental sampling results section, added a section about outbreaks caused by Legionella and other biofilm-associated pathogens, revised the contributing factors section, and created a new interventions section to capture interventions that were recommended or implemented to help stop outbreaks. Future analyses can leverage these NORS updates to improve understanding of biofilm-associated outbreaks, contributing factors, interventions, and water management program failures. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of examining data from Legionella-associated outbreak investigations, including water management program failures which can lead to improved water management practices (13,21,22). Both the Veterans Health Administration and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have directives requiring the implementation of water management programs in specific health care facilities to reduce the risk related to biofilm-associated pathogens, including Legionella (24,25).

Improvements in biofilm-associated pathogen surveillance and outbreak reporting could lead to greater outbreak detection and guide disease prevention strategies. Recent efforts to estimate the illness and health care cost impacts of waterborne disease in the United States have revealed that Legionella, NTM, and biofilm-associated pathogens have emerged as the predominant causes of hospitalizations and deaths from waterborne diseases, including those linked to drinking water exposures (3). The Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists has a standardized case definition for extrapulmonary NTM infections (opportunistic infections of wounds, soft tissue, or joints) to ensure consistency in reporting, and to identify outbreaks (26). NTM case reporting, and definitions vary across state and local public health departments, with certain departments reporting pulmonary and extrapulmonary, extrapulmonary only, or NTM site and species not specified (27–29). Health departments could consider making extrapulmonary NTM infections reportable within their jurisdictions (26). In addition, active population-based NTM surveillance, currently occurring in certain jurisdictions, will provide important data for monitoring the illness and health care cost impacts of disease, identifying affected populations, and informing public health prevention strategies (26,28).

Conclusion

Public health surveillance is essential to monitor trends in waterborne disease and detect outbreaks related to drinking water exposures. During 2015–2020, public health officials from 28 states reported 214 outbreaks associated with drinking water. These outbreaks resulted in at least 2,140 cases of illness, 563 hospitalizations (26% of cases), and 88 deaths (4% of cases). Legionella-associated outbreaks increased in number and were the leading cause of drinking water-associated outbreaks reported to NORS during the surveillance period, including hospitalizations and deaths. Primary prevention of Legionella-associated outbreaks through biofilm control and water management remains critical in health care and nonhealth care settings. Outbreaks of enteric illness primarily linked to wells represented over half of the cases during the reporting period, underscoring the importance of disease prevention efforts related to groundwater. The emergence of biofilm-associated pathogens as the primary influence of drinking water-associated outbreaks, along with the risk for enteric illness outbreaks capable of causing large numbers of cases, highlights the need for agile waterborne disease surveillance, prevention, and outbreak response programs. Drinking water source-to-tap partnership and prevention strategies are critical to addressing the emerging issue of biofilm-associated disease and to guide holistic biofilm pathogen prevention strategies. Drinking water regulations and water management programs are essential to controlling pathogens in drinking water to prevent drinking water-associated outbreaks.

Acknowledgments

Amy Freeland, Vincent Hill, Jonathan Yoder, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC; state, territory, and local waterborne disease investigators, epidemiologists, and environmental health personnel.

Corresponding author: Jasen Kunz, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC. Telephone: 770-488-7056; Email: izk0@cdc.gov.

1Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC; 2Chenega Corporation, Atlanta, Georgia; 3Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC

Conflict of Interest

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- Sinclair M, O’Toole J, Gibney K, Leder K. Evolution of regulatory targets for drinking water quality. J Water Health 2015;13:413–26. https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2014.242 PMID:26042974

- Collier SA, Deng L, Adam EA, et al. Estimate of burden and direct healthcare cost of infectious waterborne disease in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis 2021;27:140–9. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2701.190676 PMID:33350905

- Gerdes ME, Miko S, Kunz JM, et al. Estimating waterborne infectious disease burden by exposure route, United States, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis 2023;29:1357–66. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2907.230231 PMID:37347505

- CDC. Developing a water management program to reduce Legionella growth and spread in buildings. A practical guide to implementing industry standards. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/downloads/toolkit.pdf

- Benedict KM, Reses H, Vigar M, et al. Surveillance for waterborne disease outbreaks associated with drinking water—United States, 2013–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:1216–21. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6644a3 PMID:29121003

- Beer KD, Gargano JW, Roberts VA, et al. Surveillance for waterborne disease outbreaks associated with drinking water—United States, 2011–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:842–8. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6431a2 PMID:26270059

- CDC. Surveillance for waterborne disease outbreaks associated with drinking water and other nonrecreational water—United States, 2009–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013;62:714–20. PMID:24005226

- Brunkard JM, Ailes E, Roberts VA, et al.; CDC. Surveillance for waterborne disease outbreaks associated with drinking water—United States, 2007–2008. MMWR Surveill Summ 2011;60(No. SS-12):38–68. PMID:21937977

- Yoder J, Roberts V, Craun GF, et al.; CDC. Surveillance for waterborne disease and outbreaks associated with drinking water and water not intended for drinking—United States, 2005–2006. MMWR Surveill Summ 2008;57(No. SS-9):39–62. PMID:18784643

- Falkinham JO 3rd, Hilborn ED, Arduino MJ, Pruden A, Edwards MA. Epidemiology and ecology of opportunistic premise plumbing pathogens: Legionella pneumophila, Mycobacterium avium, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ Health Perspect 2015;123:749–58. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1408692 PMID:25793551

- Wikswo ME, Roberts V, Marsh Z, et al. Enteric illness outbreaks reported through the National Outbreak Reporting System—United States, 2009–2019. Clin Infect Dis 2022;74:1906–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab771 PMID:34498027

- Environmental Protection Agency. Drinking water requirements for states and public water systems. Washington, DC: Environmental Protection Agency; 2023. https://www.epa.gov/dwreginfo

- Soda EA, Barskey AE, Shah PP, et al. Health care-associated Legionnaires’ disease surveillance data from 20 states and a large metropolitan area—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:584–9. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6622e1 PMID:28594788

- Schumacher A, Kocharian A, Koch A, Marx J. Fatal case of Legionnaires’ disease after home exposure to Legionella pneumophila serogroup 3—Wisconsin, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:207–11. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6908a2 PMID:32106217

- Donohue MJ, Mistry JH, Donohue JM, et al. Increased frequency of nontuberculous mycobacteria detection at potable water taps within the United States. Environ Sci Technol 2015;49:6127–33. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b00496 PMID:25902261

- Liu S, Gunawan C, Barraud N, Rice SA, Harry EJ, Amal R. Understanding, monitoring, and controlling biofilm growth in drinking water distribution systems. Environ Sci Technol 2016;50:8954–76. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b00835 PMID:27479445

- Lee D, Murphy HM. Private wells and rural health: groundwater contaminants of emerging concern. Curr Environ Health Rep 2020;7:129–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-020-00267-4 PMID:31994010

- Woolf AD, Stierman BD, Barnett ED, et al.; Council on Environmental Health and Climate Change; Committee on Infectious Diseases. Drinking water from private wells and risks to children. Pediatrics 2023;151:e2022060644. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-060644 PMID:36995187

- CDC. Private ground water wells. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/drinking/private/wells/index.html

- Wallender EK, Ailes EC, Yoder JS, Roberts VA, Brunkard JM. Contributing factors to disease outbreaks associated with untreated groundwater. Ground Water 2014;52:886–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwat.12121 PMID:24116713

- Clopper BR, Kunz JM, Salandy SW, Smith JC, Hubbard BC, Sarisky JP. A methodology for classifying root causes of outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease: deficiencies in environmental control and water management. Microorganisms 2021;9:89. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9010089 PMID:33401429

- Garrison LE, Kunz JM, Cooley LA, et al. Deficiencies in environmental control identified in outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease—North America, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:576–84. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6522e1 PMID:27281485

- Donohue MJ, Vesper S, Mistry J, Donohue JM. Impact of chlorine and chloramine on the detection and quantification of Legionella pneumophila and Mycobacterium species. Appl Environ Microbiol 2019;85:e01942-19. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01942-19 PMID:31604766

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Requirement to reduce Legionella risk in healthcare facility water systems to prevent cases and outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2017. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/QSO17-30-HospitalCAH-NH-REVISED-.pdf

- Department of Veterans Affairs. Prevention of healthcare-associated Legionella disease and scald injury from water systems. Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs; 2022. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/publications.cfm?Pub=1

- CDC. Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/organisms/ntm/health-departments.html

- Shih DC, Cassidy PM, Perkins KM, Crist MB, Cieslak PR, Leman RL. Extrapulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease surveillance—Oregon, 2014–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:854–7. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6731a3 PMID:30091968

- Grigg C, Jackson KA, Barter D, et al. Epidemiology of pulmonary and extrapulmonary nontuberculous mycobacteria infections at 4 US emerging infections program sites: a 6-month pilot. Clin Infect Dis 2023;77:629–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad214 PMID:37083882

- Mercaldo RA, Marshall JE, Cangelosi GA, et al. Environmental risk of nontuberculous mycobacterial infection: strategies for advancing methodology. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2023;139:102305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tube.2023.102305 PMID:36706504

Abbreviation: S = suspected.

* N = 23 outbreaks.

† Etiologies listed are confirmed unless indicated as S. For multiple-etiology outbreaks, etiologies are listed in alphabetical order.

§ Community and noncommunity water systems are defined by the Environmental Protection Agency as public water systems that have ≥15 service connections or serve an average of ≥25 residents for ≥60 days per year. A community water system serves year-round residents of a community, subdivision, or mobile home park. A noncommunity water system serves an institution, industry, camp, park, hotel, or business and can be nontransient or transient. Nontransient systems serve ≥25 of the same persons for ≥6 months of the year but not year round (e.g., factories and schools), whereas transient systems provide water to places in which persons do not remain for long periods (e.g., restaurants, highway rest stations, and parks). Individual water systems are small systems not owned or operated by a water utility that have <15 connections or serve <25 persons.

¶ Two community water systems were reported for this outbreak.

Abbreviation: S = suspected.

* N = 44 outbreaks.

† Etiologies listed are confirmed unless indicated as S. For multiple-etiology outbreaks, etiologies are listed in alphabetical order.

§ Community and noncommunity water systems are defined by Environmental Protection Agency as public water systems that have ≥15 service connections or serve an average of ≥25 residents for ≥60 days per year. A community water system serves year-round residents of a community, subdivision, or mobile home park. A noncommunity water system serves an institution, industry, camp, park, hotel, or business and can be nontransient or transient. Nontransient systems serve ≥25 of the same persons for ≥6 months of the year but not year round (e.g., factories and schools), whereas transient systems provide water to places in which persons do not remain for long periods of time (e.g., restaurants, highway rest stations, and parks). Individual water systems are small systems not owned or operated by a water utility that have <15 connections or serve <25 persons.

Abbreviation: S = suspected.

* N = 38 outbreaks.

† Etiologies are confirmed unless indicated as S.

§ Community and noncommunity water systems are defined by the Environmental Protection Agency as public water systems that have ≥15 service connections or serve an average of ≥25 residents for ≥60 days per year. A community water system serves year-round residents of a community, subdivision, or mobile home park. A noncommunity water system serves an institution, industry, camp, park, hotel, or business and can be nontransient or transient. Nontransient systems serve ≥25 of the same persons for ≥6 months of the year but not year round (e.g., factories and schools), whereas transient systems provide water to places in which persons do not remain for long periods of time (e.g., restaurants, highway rest stations, and parks). Individual water systems are small systems not owned or operated by a water utility that have <15 connections or serve <25 persons.

Abbreviations: EAEC = enteroaggregative Escherichia coli; EIEC = enteroinvasive Escherichia coli; EPEC = enteropathogenic Escherichia coli; S = suspected.

* N = 44 outbreaks.

† Etiologies listed are confirmed, unless indicated as S. For multiple-etiology outbreaks, etiologies are listed in alphabetical order.

§ Community and noncommunity water systems are defined by the Environmental Protection Agency as public water systems that have ≥15 service connections or serve an average of ≥25 residents for ≥60 days per year. A community water system serves year-round residents of a community, subdivision, or mobile home park. A noncommunity water system serves an institution, industry, camp, park, hotel, or business and can be nontransient or transient. Nontransient systems serve ≥25 of the same persons for ≥6 months of the year but not year round (e.g., factories and schools), whereas transient systems provide water to places in which persons do not remain for long periods of time (e.g., restaurants, highway rest stations, and parks). Individual water systems are small systems not owned or operated by a water utility that have <15 connections or serve <25 persons.

¶ Water system classified by the regulatory authority as a noncommunity water system because of the outbreak investigation.

Abbreviation: S = suspected.

* N = 45 outbreaks.

† Etiologies listed are confirmed, indicated as S. For multiple-etiology outbreaks, etiologies are listed in alphabetical order.

§ Community and noncommunity water systems are defined by the Environmental Protection Agency as public water systems that have ≥15 service connections or serve an average of ≥25 residents for ≥60 days per year. A community water system serves year-round residents of a community, subdivision, or mobile home park. A noncommunity water system serves an institution, industry, camp, park, hotel, or business and can be nontransient or transient. Nontransient systems serve ≥25 of the same persons for ≥6 months of the year but not year round (e.g., factories and schools), whereas transient systems provide water to places in which persons do not remain for long periods of time (e.g., restaurants, highway rest stations, and parks). Individual water systems are small systems not owned or operated by a water utility that have <15 connections or serve <25 persons.

Abbreviation: S = suspected.

* N = 20 outbreaks.

† Etiologies listed are confirmed unless indicated as S.

§ Community and noncommunity water systems are defined by the Environmental Protection Agency as public water systems that have ≥15 service connections or serve an average of ≥25 residents for ≥60 days per year. A community water system serves year-round residents of a community, subdivision, or mobile home park. A noncommunity water system serves an institution, industry, camp, park, hotel, or business and can be nontransient or transient. Nontransient systems serve ≥25 of the same persons for ≥6 months of the year but not year round (e.g., factories and schools), whereas transient systems provide water to places in which persons do not remain for long periods of time (e.g., restaurants, highway rest stations, and parks). Individual water systems are small systems not owned or operated by a water utility that have <15 connections or serve <25 persons.

FIGURE 1. Number of reported drinking water-associated outbreaks,* by state of exposure — National Outbreak Reporting System, United States, 2015–2020

FIGURE 1. Number of reported drinking water-associated outbreaks,* by state of exposure — National Outbreak Reporting System, United States, 2015–2020

* N = 214 outbreaks.

* N = 214 outbreaks; N = 2,140 cases.

† Biofilm-associated drinking water outbreaks in this analysis include outbreaks caused by Legionella (n = 184), nontuberculous Mycobacteria (n = 2), and Pseudomonas (n = 1).

§ Multiple-etiology outbreaks include two enteric bacterial and parasitic; two enteric bacterial and viral; and one enteric bacterial, parasitic, or viral etiologic category.

FIGURE 2. Number of reported drinking water-associated outbreaks,*,† by month of earliest illness onset — National Outbreak Reporting System, United States, 2015–2020

FIGURE 2. Number of reported drinking water-associated outbreaks,*,† by month of earliest illness onset — National Outbreak Reporting System, United States, 2015–2020

* N = 214 outbreaks.

† Other outbreaks refers to two outbreaks of unknown etiology and one outbreak caused by a chemical or toxin.

* Biofilm-associated drinking water outbreaks in this analysis include outbreaks caused by Legionella (n = 184), nontuberculous Mycobacteria (n = 2), and Pseudomonas (n = 1).

† N = 187 outbreaks. Outbreaks include those involving community (n = 158), unknown (n = 17), individual or private (n = 6), noncommunity (n = 3), and other (n = 2) water systems.

§ One outbreak might have multiple contributing factors reported.

¶ Percentage is calculated using a denominator of 393 because 393 is the total number of contributing factors reported for the 187 outbreaks.

** Reported as distribution factor types by users but aligns more closely with premise or point-of-use factor types.

* Enteric illness-associated drinking water outbreaks include outbreaks caused by Campylobacter (n = 2), Cryptosporidium (n = 2), Escherichia coli (n = 1), Giardia (n = 3), norovirus (n = 7), Shigella (n = 4), and multiple etiologies (n = 5).

† N = 24 outbreaks. Outbreaks include those involving individual or private (n = 11), community (n = 8), and unknown (n = 5) water systems.

§ One outbreak might have multiple contributing factors reported.

¶ Percentage is calculated using a denominator of 61 because 61 is the total number of contributing factors reported for the 24 outbreaks.

FIGURE 3. Number of reported drinking water-associated outbreaks,* by water setting of exposure†,§ — National Outbreak Reporting System, United States, 2015–2020¶

FIGURE 3. Number of reported drinking water-associated outbreaks,* by water setting of exposure†,§ — National Outbreak Reporting System, United States, 2015–2020¶

* N = 214 outbreaks.

† Health care setting includes assisted living or rehabilitation facilities, hospital or health care facilities, and long-term care facilities.

§ Other setting includes grocery store, veterans’ home, shelter, and other (not specified).

¶ Other outbreaks refers to two outbreaks of unknown etiology and one outbreak caused by a chemical or toxin.

FIGURE 4. Number of reported drinking water-associated outbreak etiologies,* by Legionella compared with all other etiologies — Waterborne Disease and Outbreak Surveillance System, United States, 2007–2020

FIGURE 4. Number of reported drinking water-associated outbreak etiologies,* by Legionella compared with all other etiologies — Waterborne Disease and Outbreak Surveillance System, United States, 2007–2020

* N = 366 outbreak etiologies.

FIGURE 5. Number of reported drinking water-associated outbreaks in community and noncommunity water settings,* by Legionella compared with all other etiologies — Waterborne Disease and Outbreak Surveillance System, United States, 2007–2020

FIGURE 5. Number of reported drinking water-associated outbreaks in community and noncommunity water settings,* by Legionella compared with all other etiologies — Waterborne Disease and Outbreak Surveillance System, United States, 2007–2020

* N = 306 water settings.

Suggested citation for this article: Kunz JM, Lawinger H, Miko S, et al. Surveillance of Waterborne Disease Outbreaks Associated with Drinking Water — United States, 2015–2020. MMWR Surveill Summ 2024;73(No. SS-1):1–23. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7301a1.

MMWR and Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report are service marks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services.

References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are

provided as a service to MMWR readers and do not constitute or imply

endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content

of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed in MMWR were current as of

the date of publication.

All HTML versions of MMWR articles are generated from final proofs through an automated process. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables.

Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.