Notes from the Field: Botulism Type B After Intravenous Methamphetamine Use — New Jersey, 2020

Weekly / October 2, 2020 / 69(39);1425–1426

Michelle A. Waltenburg, DVM1,2; Valerie A. Larson, MD3; Elinor H. Naor, DO3; Timothy G. Webster, MD3; Janet Dykes, MS2; Victoria Foltz2,4; Seth Edmunds, MPH2,4; Deepam Thomas, MPH5; Joseph Kim, MD3,6; Leslie Edwards, MHS2 (View author affiliations)

View suggested citationOn May 15, 2020, a White man aged 41 years arrived at an emergency department in New Jersey with a 2-day history of new onset blurred vision, double vision, ptosis, and difficulty swallowing. He was evaluated for cerebrovascular accident (CVA [stroke]), was found to have unremarkable computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging brain scans, and was discharged with a diagnosis of diplopia (double vision). The following day, his symptoms worsened, and he visited a second emergency department with slurred speech, oral thrush, and facial weakness. Thorough skin and scalp examinations revealed peripheral phlebitis and sites of induration, but no abscesses or open wounds. He was admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of CVA and treated with antifungal medications for oral and laryngeal candidiasis.

Past medical history was notable for methamphetamine use for approximately 20 years; the patient did not report any other illicit drug use. The patient reported he had only inhaled methamphetamine in the past; however, after a 2-week abstinence, he reported that he injected methamphetamine mixed with water intravenously approximately 24–48 hours before his symptoms began. The water came from a bottle that had been open in his home for an unknown duration. This history of recent intravenous drug use raised suspicion for botulism, a paralytic illness caused by botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT). To the patient’s knowledge, no one else who had injected the same batch of methamphetamine had had an adverse reaction.

Per New Jersey Reporting Regulations (NJAC 8:57),* the suspected illness was immediately reported to the New Jersey Department of Health. After consultation with CDC, heptavalent botulinum antitoxin was released by the CDC quarantine station in New York and administered to the patient within 24 hours of admission to the hospital. He did not require ventilatory support, and his symptoms of double vision, ptosis, difficulty swallowing, and facial weakness gradually improved until hospital discharge 5 days after antitoxin administration. The patient’s mild blurred vision persisted, and he was referred for vision rehabilitation, speech and language pathology, psychiatry, and infectious disease follow-up. Serum obtained before antitoxin administration tested positive for BoNT type B by the BoNT Endopep-MS assay, a mass spectrometry–based method that rapidly detects and differentiates active BoNTs, toxic substances that inhibit normal neuromuscular function (1).

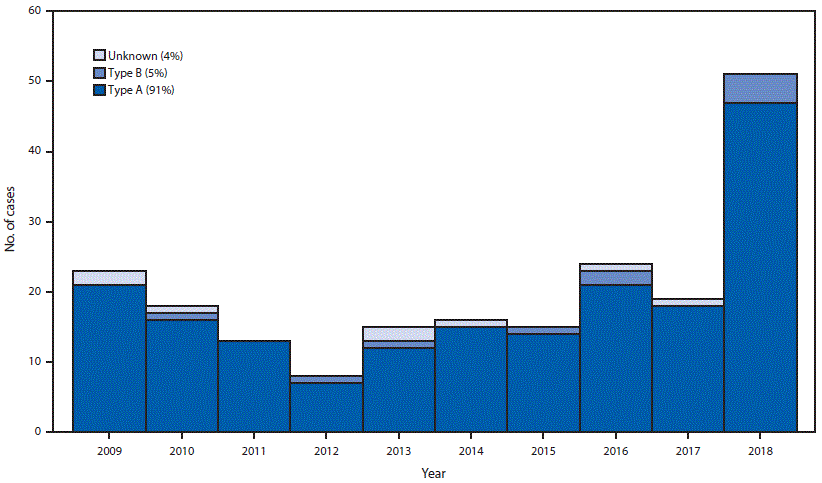

Injection drug use is the leading cause of wound botulism in the United States; most cases occur in the western and southwestern United States,† potentially associated with the supply and distribution of black tar heroin§ (2). Botulinum toxin type A is the most common toxin type among cases of wound botulism; in 2018, 47 of the 51 laboratory-confirmed cases of wound botulism were botulinum toxin type A, and injection drug use was reported by all wound botulism patients (Figure) (CDC, unpublished data, 2018). This case is notable for three reasons: 1) the rarity of botulinum toxin type B in wound botulism cases, 2) the occurrence in the northeastern United States, and 3) association with injection of methamphetamine rather than heroin.

Although most wound botulism cases are caused by black tar heroin injection (2–4), this case highlights the need for awareness of the risks for and signs and symptoms of wound botulism¶ among all persons who inject drugs, as well as among clinicians caring for persons who inject drugs. Early recognition and treatment of botulism is critical to reducing morbidity and mortality, and broader awareness of risks and symptoms of wound botulism might prompt persons who have symptoms to seek medical care early and potentially facilitate an earlier diagnosis (5). Some signs of wound botulism (e.g., ptosis and altered phonation) might be interpreted as mental status changes associated with methamphetamine abuse, highlighting the importance of conducting a thorough neurologic examination to differentiate botulism from other diagnoses (5). This case further illustrates that mild wounds can harbor Clostridia bacteria that produce botulinum toxin (5); therefore, it is important for health care providers to consider wound botulism among patients with a history of injection drug use, even in the absence of a visible abscess or severe wound.

Corresponding author: Michelle A. Waltenburg, mwaltenburg@cdc.gov.

1Epidemic Intelligence Service, CDC; 2Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC; 3Morristown Medical Center, Morristown, New Jersey; 4Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education, Oak Ridge, Tennessee; 5New Jersey Department of Health; 6ID CARE, Randolph, New Jersey.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- Barr JR, Moura H, Boyer AE, et al. Botulinum neurotoxin detection and differentiation by mass spectrometry. Emerg Infect Dis 2005;11:1578–83. CrossRef PubMed

- Werner SB, Passaro D, McGee J, Schechter R, Vugia DJ. Wound botulism in California, 1951–1998: recent epidemic in heroin injectors. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31:1018–24. CrossRef PubMed

- Peak CM, Rosen H, Kamali A, et al. Wound botulism outbreak among persons who use black tar heroin—San Diego County, California, 2017–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;67:1415–8. CrossRef PubMed

- Offerman SR, Schaefer M, Thundiyil JG, Cook MD, Holmes JF. Wound botulism in injection drug users: time to antitoxin correlates with intensive care unit length of stay. West J Emerg Med 2009;10:251–6. PubMed

- Sobel SJ. Botulism. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:1167–73. CrossRef PubMed

FIGURE. Laboratory-confirmed wound botulism cases, by year and botulinum toxin type — United States, 2009–2018*

FIGURE. Laboratory-confirmed wound botulism cases, by year and botulinum toxin type — United States, 2009–2018*

* 2018 data are provisional.

Suggested citation for this article: Waltenburg MA, Larson VA, Naor EH, et al. Notes from the Field: Botulism Type B After Intravenous Methamphetamine Use — New Jersey, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1425–1426. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6939a4.

MMWR and Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report are service marks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services.

References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are

provided as a service to MMWR readers and do not constitute or imply

endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content

of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed in MMWR were current as of

the date of publication.

All HTML versions of MMWR articles are generated from final proofs through an automated process. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables.

Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.