CDC and Food Safety

Foodborne illness is common, costly, and preventable. CDC estimates that each year 1 in 6 Americans get sick from contaminated food or beverages and 3,000 die from foodborne illness. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimates that foodborne illnesses cost the United States more than $15.6 billion each year.

CDC’s Role in Food Safety

CDC provides the vital link between foodborne illness and the food safety systems of government agencies and food producers.

CDC helps make food safer by:

Working with partners to determine the major sources of foodborne illnesses and annual changes in the number of illnesses, investigate multistate foodborne disease outbreaks, and implement systems to better prevent illnesses and detect and stop outbreaks. Government partners include state and local health departments, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service. The food industry, animal health partners, and consumers also play essential roles in food safety.

Helping state and local health departments improve the tracking and investigation of foodborne illnesses and outbreaks through surveillance systems such as PulseNet, the Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet), the System for Enteric Disease Response, Investigation, and Coordination (SEDRIC), the Foodborne Disease Outbreak Surveillance System, and other programs.

Using data to determine whether prevention measures are working and where further efforts and additional targets for prevention are needed to reduce foodborne illness.

Working with other countries and international agencies to improve tracking, investigation, and prevention of foodborne infections in the United States and around the world.

Using Advanced Technology to Find Outbreaks

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) is a tool used to generate a DNA “fingerprint.” CDC scientists and partners use WGS data to determine if strains of bacteria have similar DNA fingerprints, which could mean they come from the same source—for example, the same food or food processing facility. PulseNet public health scientists from 83 laboratories across the United States now have the tools to generate, analyze, and share WGS results with other network participants. When PulseNet scientists detect a group of illnesses caused by the same strain, disease detectives can investigate the illnesses to determine whether they came from the same food or other source.

WGS has dramatically improved our ability to link foodborne illnesses and detect outbreaks that previously would have gone undetected. WGS provides more detailed genetic information than previous DNA fingerprinting methods and helps CDC and our partners:

- Detect possible outbreaks with more precision.

- Investigate and solve outbreaks while they are still small.

- Link ill patients to likely sources of infection.

Whole genome sequencing helped CDC and FDA scientists link an E. coli outbreak in 2019 to romaine lettuce from the Salinas Valley, Calif., growing region. WGS also showed that the same strain of E. coli caused an outbreak in 2017 linked to leafy greens and an outbreak in 2018 linked to romaine lettuce.

Finding More Outbreaks Helps Make Food Safer

In recent years, even before WGS became routine, the combination of better methods for detecting outbreaks and wider distribution of foods, which can send contaminated food to many states, led to an increase in the number of multistate foodborne disease outbreaks that CDC and partners detected and investigated. Outbreak investigations often reveal problems on the farm, in processing, or in distribution that can lead to contamination before food reaches homes and restaurants. Lessons learned from outbreak investigations are helping make food safer.

Multistate Foodborne Disease Outbreaks by Year, United States, 1998–2018*

Finding Sources of Illnesses That Are Not Part of Outbreaks

Most foodborne illnesses are not associated with recognized outbreaks. Public health officials are using outbreak and other data to make annual estimates of the major food sources for all illnesses caused by priority pathogens. They are also evaluating methods to combine WGS data on isolates from ill people, foods, and animals with epidemiologic data to predict the most likely foods responsible for particular illnesses. Analyses of the major sources for all illness caused by a particular bacterium can help public health officials, regulators, industry, and consumers know which foods should be targeted for additional prevention efforts.

Challenges to America’s Food Safety

Foods we love and rely on for good health sometimes contain bacteria and other germs that can make us sick. These illnesses are deadly for some people. More prevention efforts that focus on the foods and germs responsible for the most illnesses are needed to reduce foodborne illness in the United States.

Challenges to food safety will continue to arise, in part because of:

- Changes in food production and our food supply, including central processing and widespread distribution, which mean a single contaminated food can make people sick in different parts of the country or even the world.

- New and emerging antimicrobial resistance.

- Unexpected sources of foodborne illness, such as flour and onions.

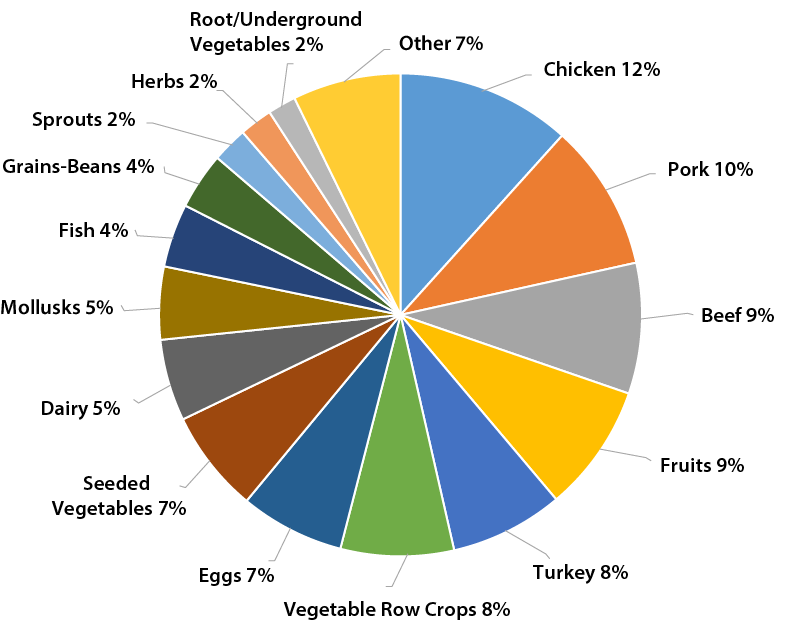

Top 15 Foods That Caused Outbreak-Associated Illnesses, 2009–2018*

| Food Category | Percentage of Outbreak-Associated Illnesses |

|---|---|

| Chicken | 12 |

| Pork | 10 |

| Beef | 9 |

| Fruits | 9 |

| Turkey | 8 |

| Vegetable Row Crops | 8 |

| Eggs | 7 |

| Seeded Vegetables | 7 |

| Dairy | 5 |

| Mollusks | 5 |

| Fish | 4 |

| Grains-Beans | 4 |

| Sprouts | 2 |

| Herbs | 2 |

| Root/Underground Vegetables | 2 |

| Other | 7 |

Notes: Vegetable row crops, e.g., leafy vegetables; seeded vegetables, e.g., cucumbers; mollusks, e.g., oysters; root/underground vegetables, e.g., carrots, potatoes.

Unpasteurized dairy products accounted for 80% of outbreak-associated illnesses linked to dairy. Pasteurized dairy products accounted for 10%, and pasteurization status was unknown for 9%.

Other = foods that don’t fit in the top 15 categories and other federally regulated items such as alcohol, coffee, other beverages, ice, condiments, and dietary supplements.

Total of percentages does not equal 100% because of rounding.

* Source: CDC Foodborne Disease Outbreak Surveillance System

The Threat of Antimicrobial Resistance

Antimicrobial-resistant bacteria develop the ability to survive or grow despite being exposed to antibiotics designed to kill them or halt their growth. Antimicrobial resistance is a global health challenge spreading through people, animals, and the environment. Though the American food supply is among the safest in the world, people can get antimicrobial-resistant infections through food. Infections with resistant bacteria cause more severe or dangerous illness than infections with nonresistant bacteria and often require more costly treatments with higher risks for side effects. Improving appropriate use of antibiotics in people and animals and strengthening food safety from farm to fork can help stop bacteria from developing resistance and can stop antimicrobial resistance from spreading.

CDC estimates that three common enteric bacteria—nontyphoidal Salmonella, Campylobacter, and Shigella—cause 740,000 antimicrobial-resistant infections each year in the United States.

Slowing the emergence of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria and preventing foodborne antimicrobial-resistant infections are complex challenges. CDC is working with partners to address these issues by:

- Supporting U.S. public health departments and national and international partners through the Antimicrobial Resistance Solutions Initiative and strengthening their ability to perform WGS on enteric bacteria such as Salmonella to determine which outbreaks are caused by antimicrobial-resistant strains.

- Using laboratory and epidemiologic data to detect emerging antimicrobial resistance and determine how resistant strains spread.

- Supporting the work FDA and USDA are doing to improve appropriate antibiotic use in veterinary medicine and agriculture.

- Ensuring veterinarians and livestock and poultry producers have tools, information, and training on antibiotic use.

- Working within the One Health framework, across the human, animal, and environmental sectors, to improve food safety and the health of people and animals.

- Foodborne Illness Surveillance Systems

- CDC Food Safety (prevention information for consumers)

- FDA Food Safety

- USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service

Download the CDC and Food Safety fact sheet. [PDF – 2 pages]