What to know

There are four types of influenza viruses: A, B, C, and D. Influenza A and B viruses cause seasonal epidemics of disease in people (known as flu season) almost every winter in the United States.

Influenza virus basics

Influenza A viruses are the only influenza viruses known to cause flu pandemics (i.e., global epidemics of flu disease). A pandemic can occur when a new and different influenza A virus emerges that infects people, can spread efficiently among people, and against which people have little or no immunity. Influenza C virus infections generally cause mild illness and are not thought to cause human epidemics. Influenza D viruses primarily affect cattle with spillover to other animals but are not known to cause illness in people.

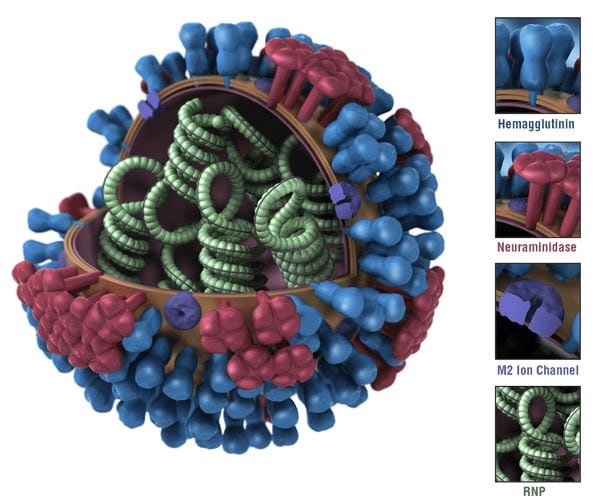

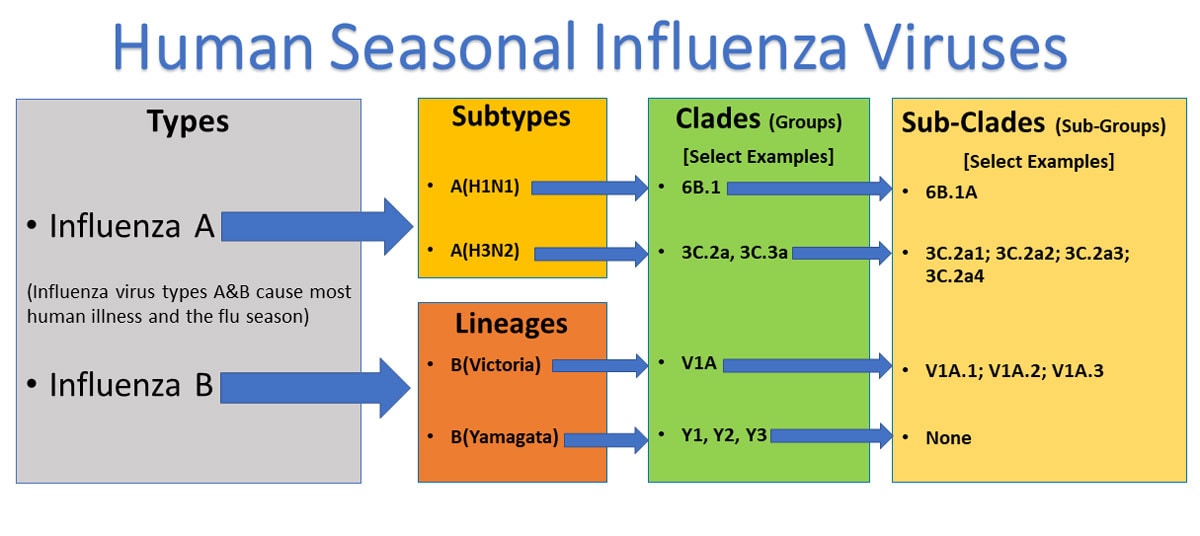

Influenza A viruses are divided into subtypes based on two proteins on the surface of the virus: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 18 hemagglutinin subtypes and 11 neuraminidase subtypes (H1 through H18 and N1 through N11, respectively). While more than 130 influenza A subtype combinations have been identified in nature, primarily from wild birds, there are potentially many more influenza A subtype combinations given the propensity for influenza viruses to “reassort”. Reassortment is when influenza viruses swap gene segments. It can occur when two different subtypes of influenza viruses infect a host at the same time and swap genetic information. Current subtypes of influenza A viruses that routinely circulate in people include A(H1N1) and A(H3N2). Influenza B viruses do not have subtypes but are distinguished by their lineage. Influenza A virus subtypes and Influenza B virus lineages can be further broken down into different HA genetic “clades” and “sub-clades.” See the “Influenza Viruses” graphic below for a visual depiction of these classifications.

Clades and sub-clades

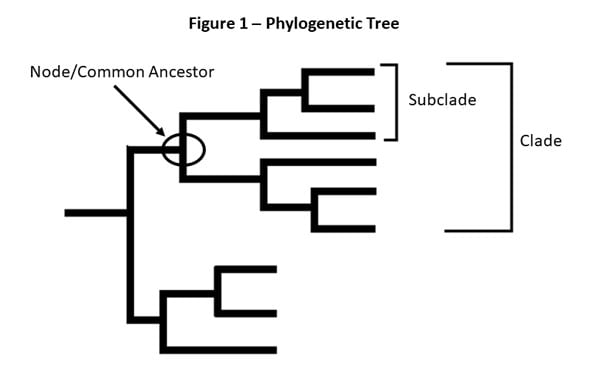

Clades and sub-clades can be alternatively called "groups" and "sub-groups," respectively. An influenza clade or group is a further classification of influenza viruses (beyond subtypes or lineages) based on the similarity of their HA gene sequences. Other gene segments also can be broken into clades and sub-clades. (See the Genome Sequencing and Genetic Characterization page for more information). Clades and subclades are shown on phylogenetic trees as groups of viruses that usually have similar genetic changes (i.e., nucleotide or amino acid changes) and have a common ancestor represented as a node in the tree (see Figure 1). Dividing viruses into clades and subclades helps flu experts track the proportion of viruses from different clades in circulation.

Note that clades and sub-clades that are genetically different are not necessarily antigenically different. This is best explained by first introducing the concepts of "antigens" and "antigenic properties". As previously described, influenza viruses have hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N) surface proteins. These proteins act as antigens. Antigens are molecular structures/proteins on the surface of viruses that are recognized by the immune system and can trigger an immune response (such as antibody production). The antigenic properties of a virus are a reflection of the antibody or immune response triggered by the specific antigens on that virus. When two influenza viruses are antigenically different, this means that a host's immune response (antibodies) elicited by infection or vaccination with one of the viruses will not as easily recognize and/or neutralize the other virus. Therefore, for antigenically different viruses, immunity against one of the viruses will not necessarily protect against the other virus.

Conversely, when two influenza viruses are antigenically similar, a host's immune response (antibodies) elicited by infection or vaccination with one of the viruses will recognize and neutralize the other virus, thereby protecting against the other virus as well.

Influenza A(H1N1) viruses

Currently circulating influenza A(H1N1) viruses are descendants of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus that emerged in the spring of 2009 and caused a flu pandemic (CDC 2009 H1N1 Flu website). These viruses, scientifically called the "A(H1N1)pdm09 virus," and more generally called "2009 H1N1," have continued to circulate seasonally since 2009 and have undergone genetic and antigenic changes.

Influenza A(H3N2) viruses also change genetically and antigenically. Influenza A(H3N2) viruses have formed many separate, genetically different clades in recent years that continue to co-circulate.

Influenza B viruses are not divided into subtypes, but instead are further classified into two lineages: B/Yamagata and B/Victoria. Similar to influenza A viruses, influenza B viruses can then be further classified into specific clades and sub-clades. Influenza B viruses generally change more slowly in terms of their genetic and antigenic properties than influenza A viruses, especially influenza A(H3N2) viruses. B/Yamagata viruses have not been detected after March 2020.

Naming influenza viruses

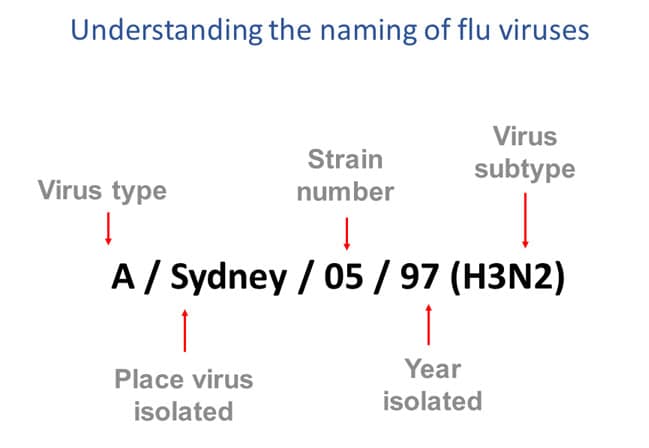

CDC follows an internationally accepted naming convention for influenza viruses. The approach uses the following components:

- The antigenic type (i.e., A, B, C, D)

- The host of origin (e.g., swine, equine, chicken, etc.). For human-origin viruses, no host of origin designation is given. Note the following examples:

- (Duck example): avian influenza A(H1N1), A/duck/Alberta/35/76

- (Human example): seasonal influenza A(H3N2), A/Perth/16/2019

- Geographical origin (e.g., Denver, Taiwan, etc.)

- Strain number (e.g., 7, 15, etc.)

- Year of collection (e.g., 57, 2009, etc.)

- For influenza A viruses, the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase antigen description are provided in parentheses (e.g., influenza A(H1N1) virus, influenza A(H5N1) virus)

- The 2009 pandemic virus was assigned a distinct name: A(H1N1)pdm09 to distinguish it from the seasonal influenza A(H1N1) viruses that circulated prior to the pandemic.

- When humans are infected with influenza viruses that normally circulate in swine (pigs), these viruses are call variant viruses and are designated with the letter "v" (e.g., an A(H3N2)v virus).

Influenza vaccine viruses

Seasonal flu vaccines in the United States are formulated to protect against three influenza viruses known to cause human epidemics, including: one influenza A(H1N1) virus, one influenza A(H3N2) virus, and one influenza B/Victoria lineage virus. Getting a flu vaccine can reduce the risk of infection with representative or antigenically similar viruses. Information about the composition of this season's vaccine can be found at Preventing Seasonal Flu with Vaccination. Seasonal flu vaccines do not protect against influenza C or D viruses or against zoonotic (animal-origin) influenza viruses that can cause human infections, such as variant or avian (bird) influenza viruses. In addition, flu vaccines will NOT protect against infection and illness caused by other respiratory viruses. There are many other viruses besides influenza that can result in influenza-like illness (ILI) that spread during flu season.