Where Resistance Spreads: Water, Soil, & the Environment

Human activity can contaminate the environment (water, soil) with antibiotics and antifungals, which can speed up the development and spread of resistance. Contamination can occur from:

- Human and animal waste

- Use of antibiotics and antifungals as pesticides on plants or crops

- Pharmaceutical manufacturing waste

Scientific evidence from a report called Initiatives for Addressing Antimicrobial Resistance in the Environment [PDF – 94 pages] show that traces of antibiotics and antifungals, germs resistant to them, and genes that cause resistance traits are present and can spread in waterways and soils. However, scientists do not fully understand the risk of resistance in the environment on human health.

Measuring the relationship between resistant germs and genes, drug residues (small amounts of leftover drugs or pieces of drugs that are not completely absorbed by the body), the environment, and human health is complex and incomplete. CDC and partners are doing innovative research to better understand the spread of resistance in the environment and the impact on human health.

How Germs Can Spread in the Environment & About Antibiotic/Antifungal Use

Human Waste

Fecal waste (poop) can carry traces of previously consumed antibiotics, antifungals, and antimicrobial-resistant germs. This waste and wastewater can contribute to the development and spread of antimicrobial-resistant germs in the environment, and possibly have a negative impact on human health.

Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) reduce contaminants in wastewater before discharging the treated water into waterways. However, some antibiotic and antifungal residues and resistant germs and genes can survive treatment because wastewater treatment systems are not specifically designed to kill or remove them.

Studies have found measurable levels of resistant bacteria in surface waters (rivers, coastal waters) because of sewage leaks, overflow, or release of untreated or undertreated wastewater discharge. This caused illness in some people who were exposed to these germs through contaminated water.

The presence of antimicrobial-resistant germs in human waste is especially challenging for wastewater from inpatient healthcare facilities like hospitals. Patients at healthcare facilities can shed some of the deadliest germs from resistant infections and are commonly prescribed antibiotics and antifungals.

Water and sanitation systems, and the degree to which they prevent or spread resistance, varies greatly throughout the world and between communities. Many countries face challenges in providing adequate sanitation—the ability to dispose of human waste safely and maintain hygienic conditions.

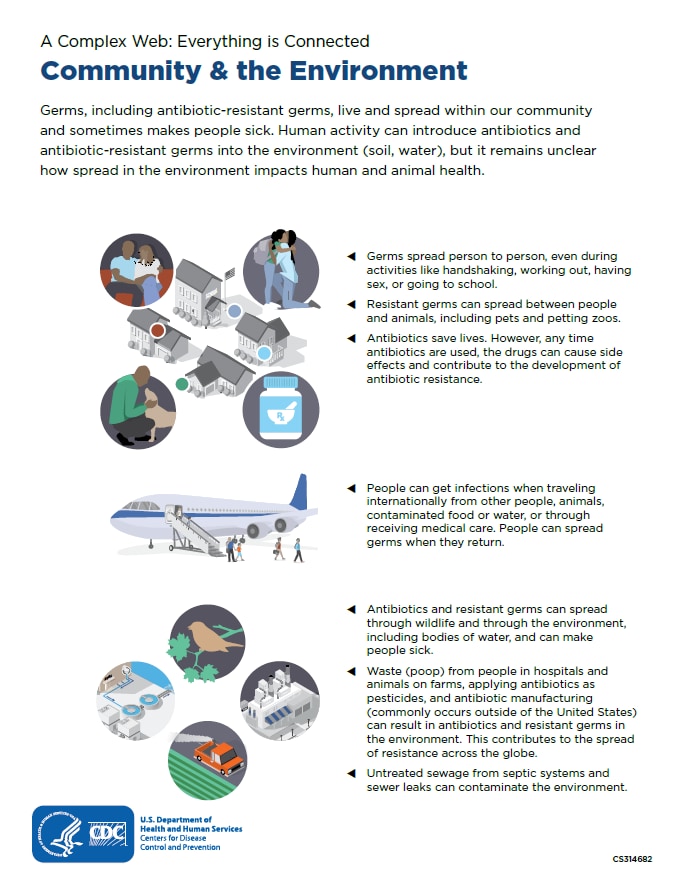

Download a printable fact sheet highlighting information on this webpage: Everything is Connected: Community & the Environment [PDF – 1 page].

COVID-19 Impacts Antimicrobial Resistance

Much of the U.S. progress in combating antimicrobial resistance was lost in 2020, in large part, due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic pushed healthcare facilities, health departments, and communities near their breaking points.

Find out more about the impact of COVID-19 on antimicrobial resistance in the U.S.

Globally, most human waste is discharged directly into the environment without treatment. This includes open defecation and discarding untreated waste into waterways. Advancements in sanitation systems and improving antibiotic and antifungal use will help slow the development of resistance.

Animal Waste

Antibiotics and antifungals are sometimes given to food animals to treat, control, and prevent diseases. Like human waste, manure from food-producing animals treated with antibiotics and antifungals can carry drug residues and resistant germs. This could contaminate the surrounding soil and nearby water sources. Animal waste is often used as fertilizer on agricultural lands to help with plant growth. While more research is needed, using untreated or un-composted animal manure that contains residues or resistant germs as fertilizer can contribute to the development and spread of resistant germs through the environment.

Pesticides

Various diseases can infect plants and crops (e.g., wheat, oranges, corn). These diseases can be difficult to control and extremely damaging because they can impact farm income and the food supply. Antibiotics and antifungals (fungicides) are sometimes applied as pesticides to manage plant and crop diseases. However, using antibiotics and fungicides in agriculture can contribute to resistance in the environment by contaminating soil and water. For example, stormwater and irrigation water from farmland can contaminate nearby bodies of water with resistant germs and antibiotic or antifungal residues.

This contamination can affect human health when the pesticides are the same as, or closely related to, antibiotics and antifungals used in human medicine. For example, triazoles are the most widely used fungicides on plants and crops, but are also similar to important human antifungal medicines used to prevent or treat fungal infections caused by germs like Aspergillus fumigatus. Patients with azole-resistant A. fumigatus infections are up to 33% more likely to die than patients with infections that can be treated with azoles. Use of triazole fungicides in the environment increased more than four times from 2006 to 2016 in the U.S. alone. Appropriate use of azoles in human medicine and agriculture can help combat resistance.

Aquaculture

Antibiotics and antifungals are used worldwide in aquaculture (the farming of fish and seafood) to control disease. Using antibiotics and antifungals in aquaculture can contaminate the local aquatic environment with these drugs and residues. There are limited data on antibiotic and antifungal use in aquaculture and its impacts on human health.

Drinking Water

Safe water is water that is clean to drink, accessible when needed, and free from germs and chemicals. Globally, access to safe water and basic sanitation can reduce the spread of resistant germs in the environment and between people, causing fewer waterborne infections and the need for antibiotics and antifungals.

Worldwide, in 2017, 780 million people did not have access to at least basic water services. Additionally, more than 2 billion people lacked access to basic sanitation (more than 25% of the world’s population). The World Health Organization estimates that if everyone had access to improved drinking water and sanitation, diarrheal illnesses that are treated with antibiotics would be reduced by 60%. Learn more about how antimicrobial resistance spreads across the world and how to protect yourself from waterborne diseases.

AMR Exchange Webinar

In August 2021, CDC hosted its second AMR Exchange webinar exploring antimicrobial resistance in water, the impact on public health, and action to address this potential threat. The panel includes experts from CDC, The Ohio State University, and the University of Gothenburg.