At a glance

- Candidemia is a bloodstream infection caused by the fungus Candida.

- It is one of the most common bloodstream infections in the United States.

- An estimated 25,000 cases of candidemia occur in the United States each year.

- Candidemia is associated with high rates of death.

Candidemia

Hospitalized patients, typically those who are very sick, can get invasive candidiasis, Candida infections in their bloodstream, joints, or organs. Candidemia refers specifically to bloodstream infections with Candida, the most common type of invasive infections.

Additionally, candidemia is one of the most common bloodstream infections in the US.1 Surgical wounds and invasive medical devices like catheters, central venous lines, and ventilators create opportunities for Candida to enter the body.

Candidemia surveillance

As part of CDC's Emerging Infections Program (EIP), the Candida Bloodstream Infections Activity:

- Monitors epidemiologic trends in candidemia.

- Performs species confirmation.

- Conducts antifungal susceptibility testing.

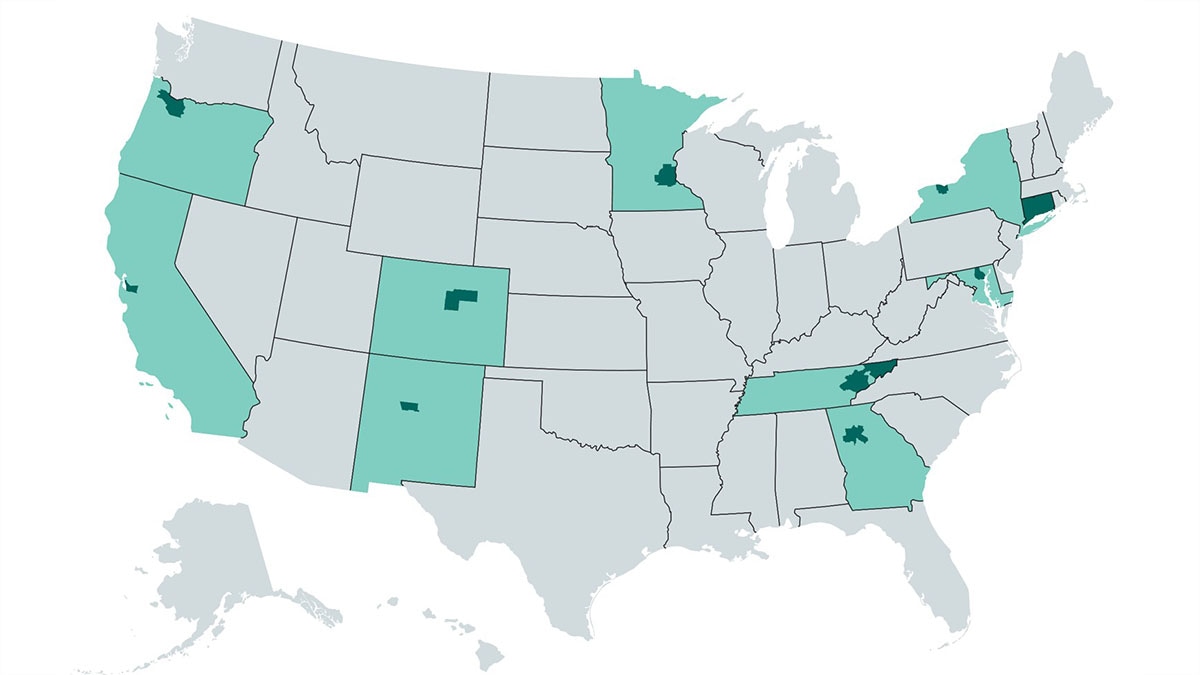

To collect this information, trained professionals conduct active population- and laboratory-based surveillance in 10 EIP sites.

Healthcare-associated infection surveillance

CDC also collects data on healthcare-associated infections, including central line-associated Candida infections, through the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN), the largest healthcare-associated infection reporting system in the United States.

Candidemia trends

National trends

An estimated 25,000 cases of candidemia occur in the United States each year.2

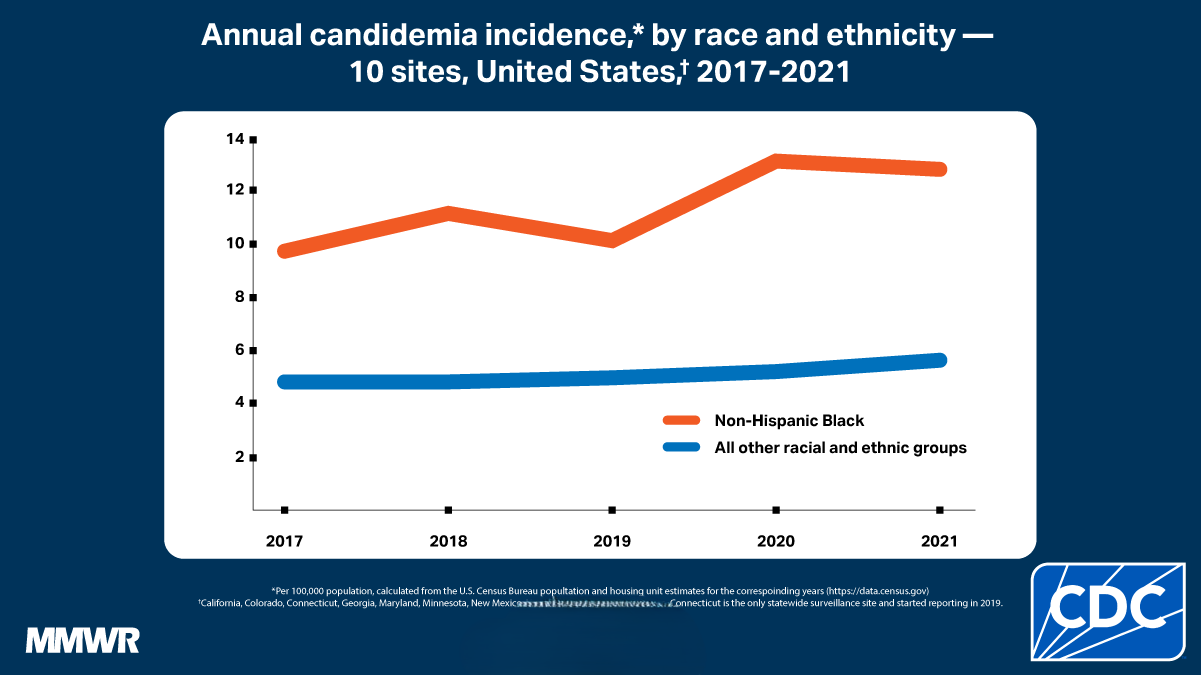

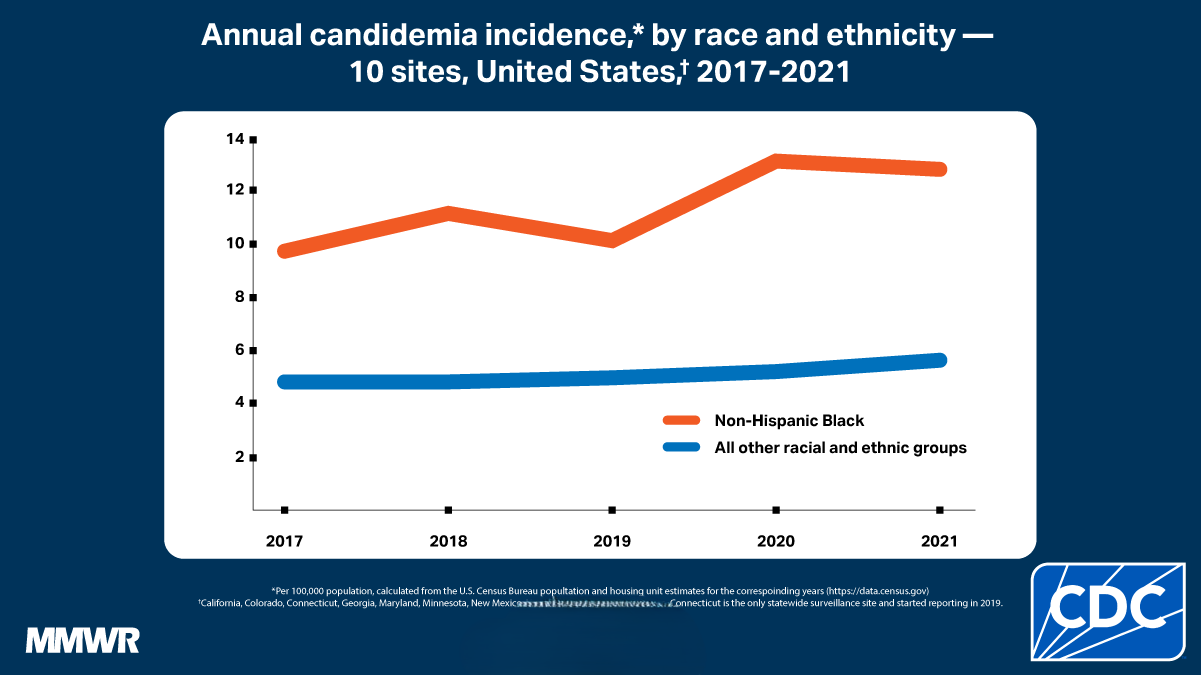

Candidemia incidence declined during 2008–2013 and then remained at approximately 9 cases per 100,000 population per year during 2012–2016.34During 2017–2021, the overall candidemia incidence was approximately 7 cases per 100,000 population, with the highest incidence in 2021 (8 cases per population).

Mortality

About one third of people with candidemia die during hospitalization (crude mortality rate), according to CDC surveillance. However, candidemia tends to affect patients who are already very sick so it is often difficult to determine whether candidemia is the cause of death versus other medical factors.

One study compared patients with candidemia to patients without candidemia who had similar illnesses. The results indicated that candidemia was the cause of about 19%-24% of deaths among infected patients.5

Injection drug use

Although the overall national incidence has declined, incidence increased in some surveillance areas in recent years. This may be due to the growing number of cases linked to injection drug use.678 From 2012-2016, about 10% of cases occurred in patients with a history of injection drug use, mostly in younger adults.4This percentage declined to 7% in 2021.

Species distribution and antimicrobial resistance

Trends in species distribution

Up to 95% of all Candida bloodstream infections in the United States are caused by five species of Candida: C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, and C. krusei. The proportion of infections caused by each species varies by geographic region and by patient population.9

- Overall, C. albicans is the leading cause of candidemia.

- Infections with antifungal-resistant non-albicans may be increasing.101112

- Non-albicans species cause approximately two-thirds of cases.310

- In some locations, C. glabrata is the most common species.

Trends in antimicrobial resistance

Some types of Candida are increasingly resistant to first-line and second-line antifungal medications. These antifungals include fluconazole and echinocandins (anidulafungin, caspofungin, and micafungin).

Fluconazole resistance

About 6% of all Candida bloodstream isolates tested at CDC are resistant to fluconazole. CDC's surveillance data indicate that the proportion of Candida isolates resistant to fluconazole has remained fairly constant over the past 20 years.101314

Echinocandin resistance

Echinocandin resistance appears to be emerging, especially among C. glabrata isolates. Approximately 2% of C. glabrata isolates are resistant to echinocandins, but the percentage may be higher in some hospitals. Echinocandins remain the first-line treatment for C. glabrata, which already has high levels of resistance to fluconazole.15

Populations

Candidemia is most common among people over 65 years old in infants less than one year old.

Among all ages, candidemia rates are approximately twice as high among Black people compared with other races/ethnicities. The differences by race might be due to differences in underlying conditions, socioeconomic status, healthcare access and availability, or other factors.

Learn more about candidemia incidence rates by age group and race.

Impacts

Leading cause of healthcare-associated bloodstream infections

Candida is a leading cause of healthcare-associated bloodstream infections in U.S. hospitals. Invasive Candida infections are costly for patients and healthcare facilities because of the long hospital stays. According to estimates, each case requires about 3 to 13 additional days of hospitalization and $6,000 to $29,000 in healthcare costs.5

Outbreaks and clusters

Most cases of invasive candidiasis are not associated with outbreaks. However, periodic outbreaks of C. parapsilosis infection have been reported for decades. This includes clusters in neonatal intensive care units, likely transmitted via healthcare workers' hands.161718

- Magill SS, O'Leary E, Janelle SJ, Thompson DL, Dumyati G, Nadle J, et al. Changes in prevalence of health care-associated infections in U.S. hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(18):1732-1744.

- Tsay SV, Mu Y, Williams S, Epson E, Nadle J, Bamberg WM, et al. Burden of Candidemia in the United States, 2017. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(9):e449-e453.

- Cleveland AA, Harrison LH, Farley MM, Hollick R, Stein B, Chiller TM, et al. Declining incidence of candidemia and the shifting epidemiology of Candida resistance in two US metropolitan areas, 2008-2013: results from population-based surveillance. PloS one 2015;10:e0120452.

- Toda M, Williams SR, Berkow EL, et al. Population-based active surveillance for culture-confirmed candidemia — four sites, United States, 2012–2016. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2019 Sep 27.

- Morgan J, Meltzer MI, Plikaytis BD, Sofair AN, Huie-White S, Wilcox S, et al. Excess mortality, hospital stay, and cost due to candidemia: a case-control study using data from population-based candidemia surveillance. Infect Control Hospital Epidemiol 2005;26:540-7.

- Poowanawittayakom N, Dutta A, Stock S, Touray S, Ellison RT 3rd, Levitz SM. Reemergence of intravenous drug use as risk factor for candidemia, Massachusetts, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(4):631–7.

- Zhang AY, Shrum S, Williams S, Petnic S, Nadle J, Johnston H, et al. The changing epidemiology of candidemia in the United States: Injection drug use as an increasingly common risk factor-active surveillance in selected sites, United States, 2014-2017. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(7):1732-1737.

- Rossow JA, Gharpure R, Brennan J, Relan P, Williams SR, Vallabhaneni S, et al. Injection drug use-associated candidemia: Incidence, clinical features, and outcomes, East Tennessee, 2014-2018. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(Suppl 5):S442-S450.

- Lockhart S. Current epidemiology of Candida infection. Clin Microb News. 2014;36:131-6.

- Lockhart SR, Iqbal N, Cleveland AA, Farley MM, Harrison LH, Bolden CB, et al. Species identification and antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida bloodstream isolates from population-based surveillance studies in two U.S. cities from 2008 to 2011. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(11):3435-42.

- Pfaller M, Neofytos D, Diekema D, Azie N, Meier-Kriesche HU, Quan SP, Horn D. Epidemiology and outcomes of candidemia in 3648 patients: Data from the Prospective Antifungal Therapy (PATH Alliance®) registry, 2004-2008. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;74(4):323-31.

- Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clin Microbiol Rev 2007;20:133-63.

- Hajjeh RA, Sofair AN, Harrison LH, Lyon MG, Arthington-Skaggs BA, Mirza SA et al. Incidence of bloodstream infections due to Candida species and in vitro susceptibilities of isolates collected from 1998 to 2000 in a population-based active surveillance program. J Clin Microbiol 2004;42:1519-27.

- Kao AS, Brandt ME, Pruitt WR, Conn LA, Perkins BA, Stephens DS, et al. The epidemiology of candidemia in two United States cities: results of a population-based active surveillance. Clin Infect Dis 1999;29:1164-70.

- Vallabhaneni S, Cleveland AA, Farley MM, Harrison LH, Schaffner W, Beldavs ZG, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors for echinocandin nonsusceptible Candida glabrata bloodstream infections: data from a large multisite population-based candidemia surveillance program, 2008-2014. Open Forum Infect Dis 2015;2:ofv163.

- Lupetti A, Tavanti A, Davini P, Ghelardi E, Corsini V, Merusi I, et al. Horizontal transmission of Candida parapsilosis candidemia in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40(7):2363-9.

- Clark TA, Slavinski SA, Morgan J, Lott T, Arthington-Skaggs BA, Brandt ME, et al. Epidemiologic and molecular characterization of an outbreak of Candida parapsilosis bloodstream infections in a community hospital. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(10):4468-72.

- Huang YC, Lin TY, Leu HS, Peng HL, Wu JH, Chang HY. Outbreak of Candida parapsilosis fungemia in neonatal intensive care units: Clinical implications and genotyping analysis. Infection. 1999;27(2):97-102.

- Benedict K, Roy M, Kabbani S, Anderson EJ, Farley MM, Harb S, et al. Neonatal and pediatric candidemia: Results from population-based active laboratory surveillance in four US locations, 2009-2015. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2018;7(3):e78-e85.

- Cleveland AA, Farley MM, Harrison LH, Stein B, Hollick R, Lockhart SR, et al. Changes in incidence and antifungal drug resistance in candidemia: Results from population-based laboratory surveillance in Atlanta and Baltimore, 2008-2011. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(10):1352-61.

- Candida auris is more transmissible than other Candida species and is associated with outbreaks in healthcare facilities.