About

- This ACIP GRADE handbook provides guidance to the ACIP workgroups on how to use the GRADE approach for assessing the certainty of evidence.

Summary

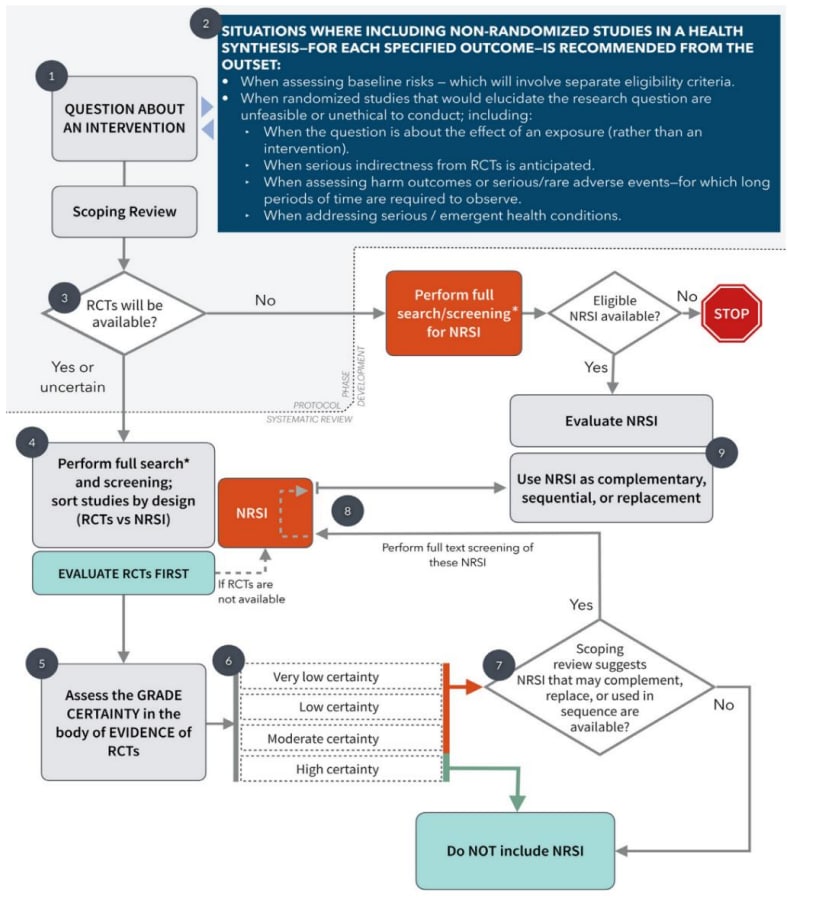

As described in section 4, authors at the protocol stage may decide that both RCTs and NRS need to be considered, and both types of evidence are retrieved and evaluated. Once the search is complete, the evidence is organized by study design as either randomized or non-randomized. The GRADE certainty of the RCTs should be evaluated first. After assessing each outcome separately, if there is high certainty in the body of evidence coming from RCTs, there is no need to further evaluate or use the NRS to complement or replace the RCTs. If the certainty of evidence from NRS is higher than RCTs, they can be considered as replacement evidence, especially if the NRS have low concerns with indirectness and imprecision. Reviewers might consider using NRS to complement evidence if RCTs do not provide data on populations of interest, or if the NRS studies provide evidence for possible effect modification. Figure 9 provides a visual representation of when NRS may be needed to support evidence from RCTs.

Figure 9: Flow chart depicting when to integrate RCTs and NRS in the evidence synthesis

References in this figure: 1

When high certainty evidence for an outcome is not available in the RCT body of evidence, NRS can be used. There are two scenarios in which this may occur1:

- When evidence from RCTs has low or very low certainty, NRS could help increase the overall certainty in the results. The NRS should be evaluated and if the certainty in the evidence is equal to or better than the certainty level of the RCTs, both types of evidence can be used in the decision-making process.

- When evidence from RCTs is moderate, NRS can be used to mitigate concerns with indirectness (e.g., baseline risk in the population may not represent the target population). In this situation, it is unlikely to find NRS that will have an equal or better certainty level than the RCTs as NRS can only be deemed moderate or high certainty if there is a reason to upgrade the evidence level (see section 7). It is important to remember that while NRS can provide context to RCTs, they should not be used as evidence to make judgements about directness when grading the certainty in the RCTs; directness should still be judged based on how closely the evidence answers the research question2. Below are two examples of how NRS help contextualize RCTs.

- If an RCT was conducted in men and the target population in the research question was women, NRS may be used to make judgements about the certainty in these results. If the NRS shows the intervention has the same effect in both men and women, then the NRSs can be used to complement the RCT. Conversely, if the studies had shown that there was a notable difference in men and women, the overall certainty in the RCT evidence may need to be downgraded.

- When the RCT evidence does not provide enough information about baseline risk of the control event, NRS may be used. For example, if the PICO question specified children between the ages of 12 and 15 as the target population, however the RCT evidence only provided baseline risk for children under the age of 5, NRS could be used to provide the control event rate for the target age group. The NRS could provide evidence that shows the baseline risk varies between populations or supports the evidence from the RCT.

- If an RCT was conducted in men and the target population in the research question was women, NRS may be used to make judgements about the certainty in these results. If the NRS shows the intervention has the same effect in both men and women, then the NRSs can be used to complement the RCT. Conversely, if the studies had shown that there was a notable difference in men and women, the overall certainty in the RCT evidence may need to be downgraded.

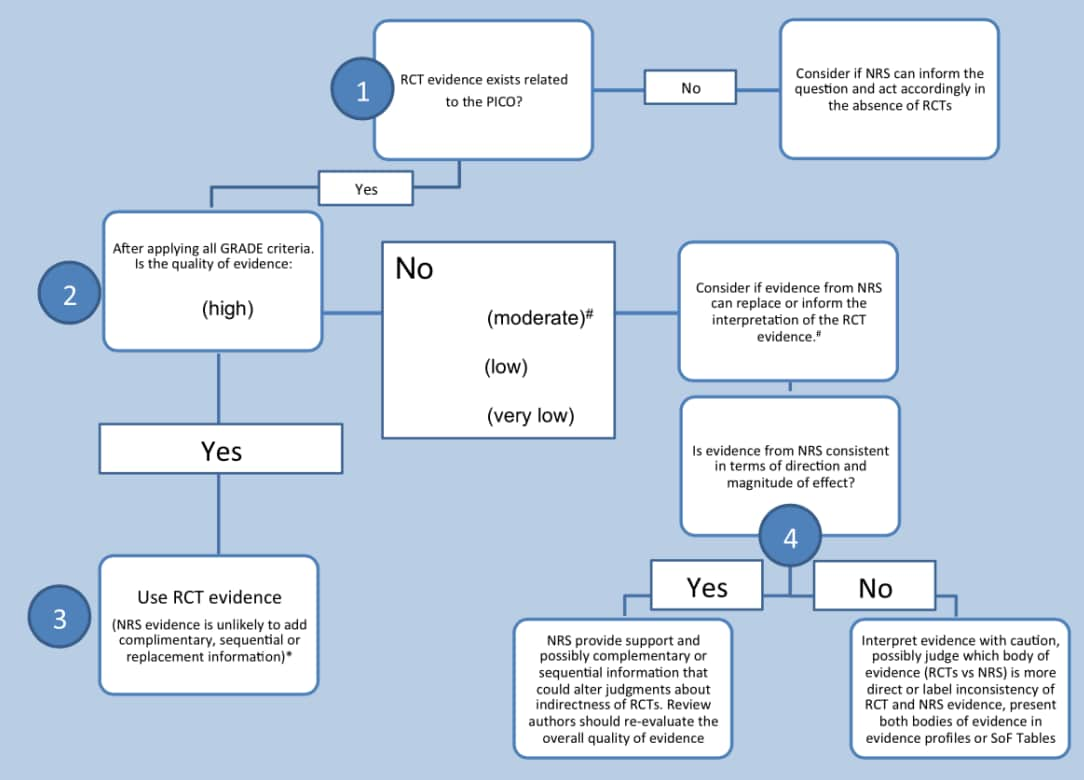

When either of the two scenarios that result in the use of NRS occur, there are three ways in which the evidence can interact with the RCTs (Figure 10)2

- Complementary NRS: The NRS can provide information on whether the intervention works similarly in different populations or if there are differential baseline risks between populations. Therefore, when the RCT evidence is indirect, NRS can be used to complement and contextualize as seen in the examples above.

- Sequential NRS: When evidence from RCTs is not sufficient, NRS can help by providing additional information. For example, NRS could provide information on long-term outcomes for patients involved in short-term RCTs. Additionally, when RCTs use surrogate outcomes, the NRS could help determine if the surrogate is relevant to patient-important outcomes.

- Replacement NRS: When the NRS is assessed and the results have a higher level of certainty than the body of evidence from RCTs, the NRS may replace the RCTs. In spite of the lack of randomization, if the NRS is more direct and has better certainty, then decision-makers can consider the NRS as the best available evidence.

Figure 10. Steps that systematic review authors might follow when considering NRS evidence (adapted)

References in this figure: 2

Figure 10 provides an overview of the steps taken when deciding whether to use NRS in addition to evidence from RCTs. When presenting both NRS and RCTs for an outcome in a systematic review, the results can either be presented separately as a narrative synthesis, in separate meta-analysis as a quantitative synthesis or a combination of the two1.

- Cuello-Garcia CA, Santesso N, Morgan RL, et al. GRADE guidance 24 optimizing the integration of randomized and non-randomized studies of interventions in evidence syntheses and health guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 2022/02// 2022;142:200-208. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.11.026

- Schünemann HJ, Tugwell P, Reeves BC, et al. Non-randomized studies as a source of complementary, sequential or replacement evidence for randomized controlled trials in systematic reviews on the effects of interventions. Research Synthesis Methods. 2013 2013;4(1):49-62. doi:10.1002/jrsm.1078