|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

| Recommendations and Reports |

| June 11, 2004 / 53(RR08);1-27 |

|

|

|

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Medical Examiners, Coroners, and Biologic TerrorismA Guidebook for Surveillance and Case Management Prepared by Kurt B. Nolte, M.D.,1,2* Randy L. Hanzlick, M.D.,2,3* Daniel C. Payne, Ph.D.,4 Andrew T. Kroger, M.D.,5 William R. Oliver, M.D.,6* Andrew M. Baker, M.D.,7* Dennis E. McGowan,3* Joyce L. DeJong, D.O.,8* Michael R. Bell, M.D.,7 Jeannette Guarner, M.D.,9 Wun-Ju Shieh, M.D., Ph.D.,9 and Sherif R. Zaki, M.D., Ph.D.9 1University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, New Mexico; 2Division of Public Health Surveillance and Informatics, Epidemiology Program Office, CDC; 3Fulton County Medical Examiner's Office, Atlanta, Georgia; 4Epidemiology and Surveillance Division, National Immunization Program, CDC; 5Immunization Services Division, National Immunization Program, CDC; 6Georgia Bureau of Investigation, Trion, Georgia; 7Hennepin County Medical Examiner's Office, Minneapolis, Minnesota; 8Sparrow Hospital, Lansing, Michigan; and 9Division of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, CDC The material in this report originated in the Epidemiology Program Office, Stephen B. Thacker, M.D., M.Sc., Director; the Division of Public Health Surveillance and Informatics, Richard Hopkins, M.D., M.S.P.H., Acting Director; the National Center for Infectious Diseases, James M. Hughes, M.D., Director; and the Division of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases, James LeDuc, Ph.D., Sc.D., Director.

SummaryMedical examiners and coroners (ME/Cs) are essential public health partners for terrorism preparedness and response. These medicolegal investigators support both public health and public safety functions and investigate deaths that are sudden, suspicious, violent, unattended, and unexplained. Medicolegal autopsies are essential for making organism-specific diagnoses in deaths caused by biologic terrorism. This report has been created to 1) help public health officials understand the role of ME/Cs in biologic terrorism surveillance and response efforts and 2) provide ME/Cs with the detailed information required to build capacity for biologic terrorism preparedness in a public health context. This report provides background information regarding biologic terrorism, possible biologic agents, and the consequent clinicopathologic diseases, autopsy procedures, and diagnostic tests as well as a description of biosafety risks and standards for autopsy precautions. ME/Cs' vital role in terrorism surveillance requires consistent standards for collecting, analyzing, and disseminating data. Familiarity with the operational, jurisdictional, and evidentiary concerns involving biologic terrorism-related death investigation is critical to both ME/Cs and public health authorities. Managing terrorism-associated fatalities can be expensive and can overwhelm the existing capacity of ME/Cs. This report describes federal resources for funding and reimbursement for ME/C preparedness and response activities and the limited support capacity of the federal Disaster Mortuary Operational Response Team. Standards for communication are critical in responding to any emergency situation. This report, which is a joint collaboration between CDC and the National Association of Medical Examiners (NAME), describes the relationship between ME/Cs and public health departments, emergency management agencies, emergency operations centers, and the Incident Command System. IntroductionTerrorist events in recent years have heightened awareness of the risk of terrorist acts involving unconventional agents, including biologic and chemical weapons. The need for terrorism preparedness and planning for response at multiple levels is now recognized, including planning and response by medical examiners, coroners (ME/Cs), and the medicolegal death-investigation system. Federal, state, and local agencies have developed plans to detect and respond to terrorism by using a multidisciplinary approach that requires active participation of health-care providers, law enforcement, and public health and safety staff. Because ME/Cs have expertise in disease surveillance, diagnosis, deceased body handling, and evidence collection, they serve a vital role in terrorism preparedness and response. ME/Cs should ensure that their role in surveillance for unusual deaths --- and response to known terrorist events --- is a critical part of the multidisciplinary response team. Terrorism-related drills and practical exercises conducted by public health, law enforcement, and public safety agencies should include training on postmortem operations and services. This report, prepared as a joint effort between the National Association of Medical Examiners (NAME) and CDC, is a first step in providing specific guidance to ME/C death investigators and public health officials. This report can help bridge gaps that exist in local terrorism preparedness and response planning. By discussing the substantial contributions of ME/Cs, this report can also serve as a foundation for identifying the needs of medicolegal death-investigation systems and for addressing those needs through adequate training and funding. This report provides guidance, identifies support services and resources, and discusses the roles and responsibilities of ME/Cs and affiliated personnel in recognizing and responding to potential biologic terrorism events. Certain questions being asked by ME/Cs and their public health partners are answered in this report, including the following:

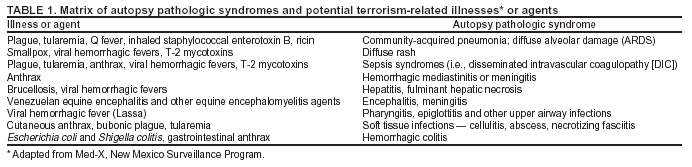

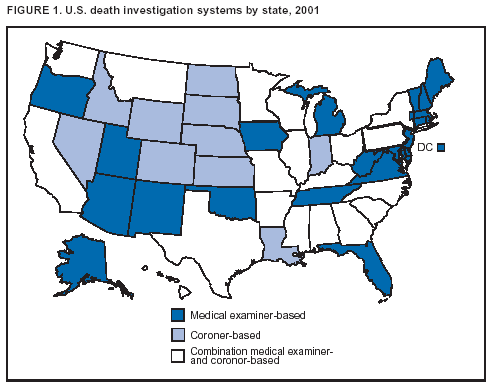

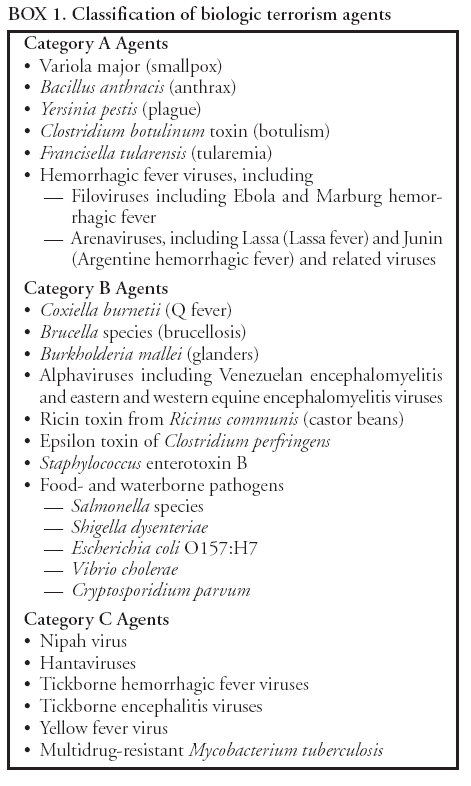

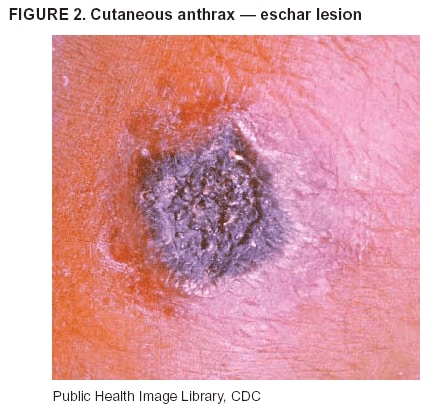

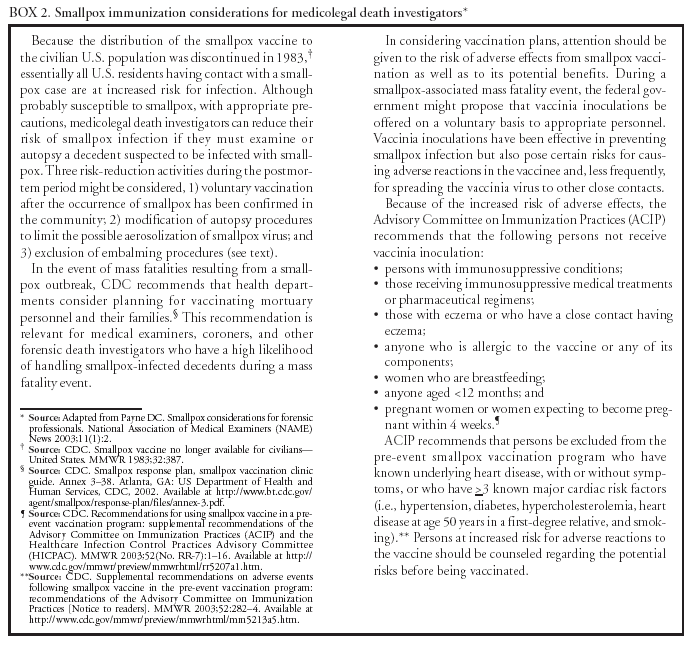

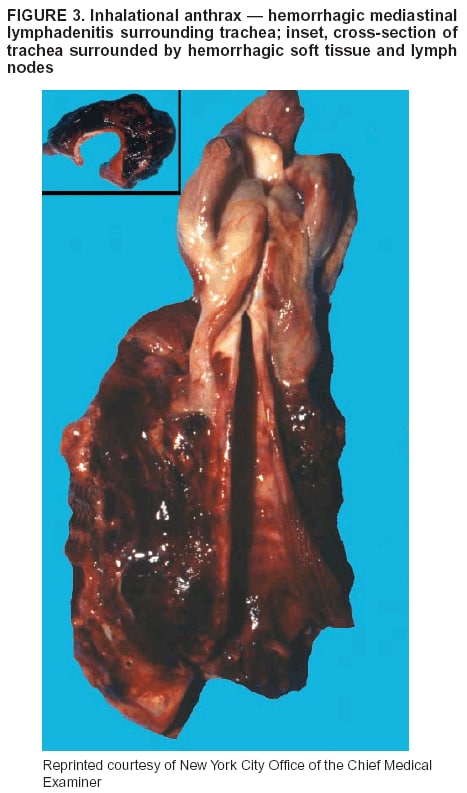

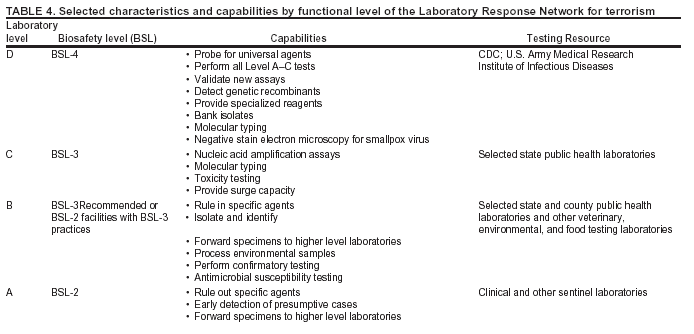

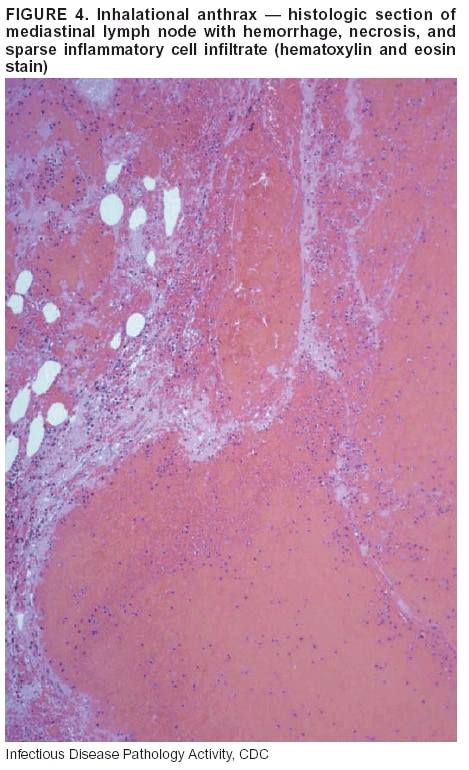

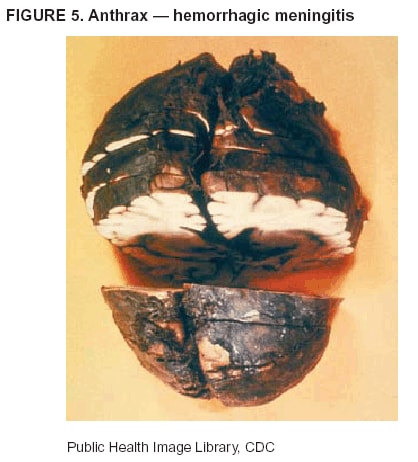

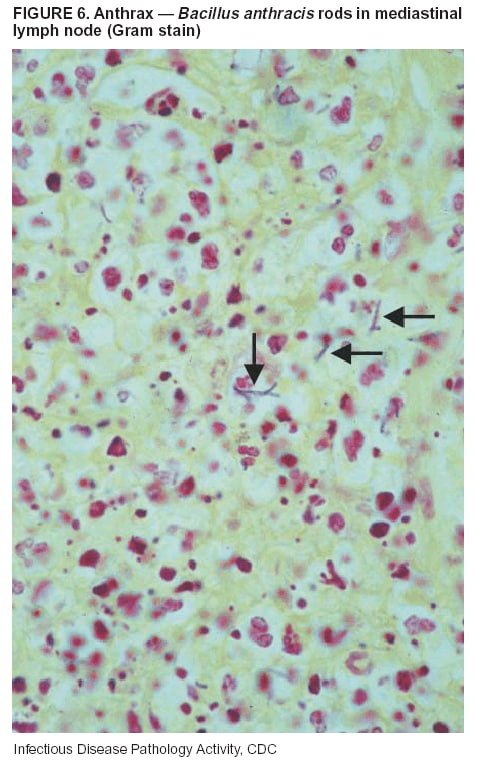

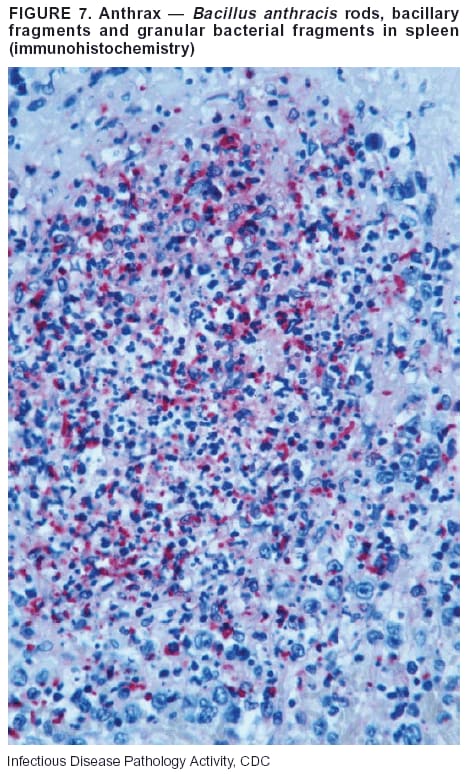

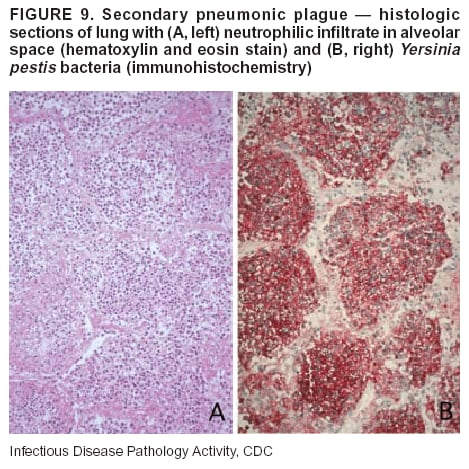

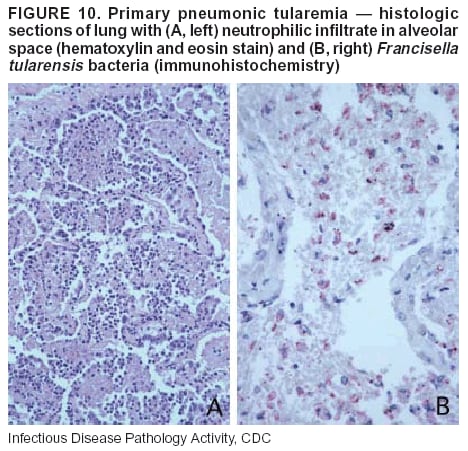

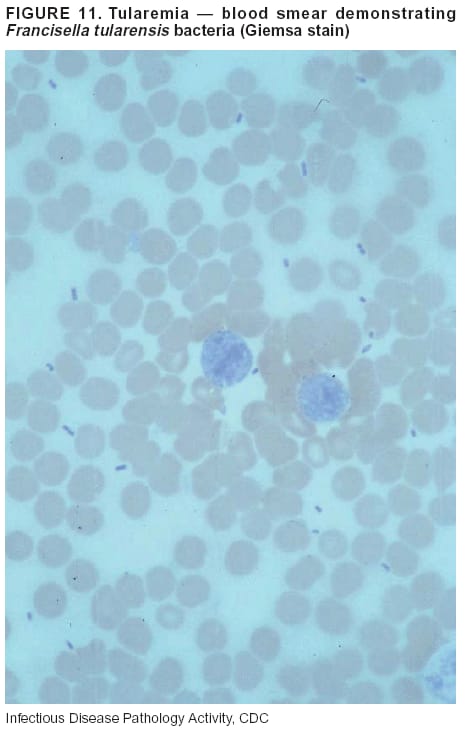

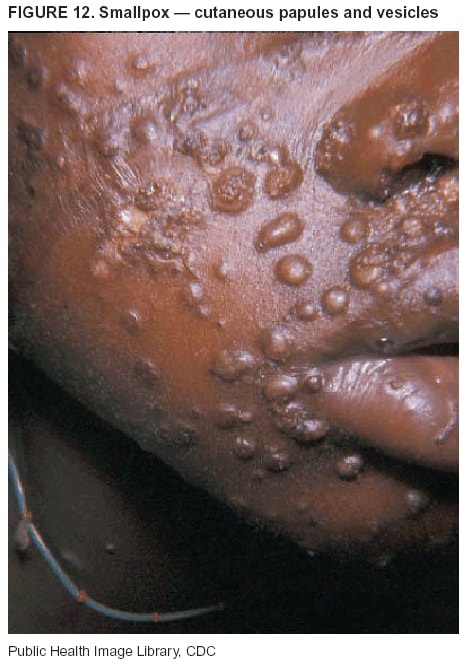

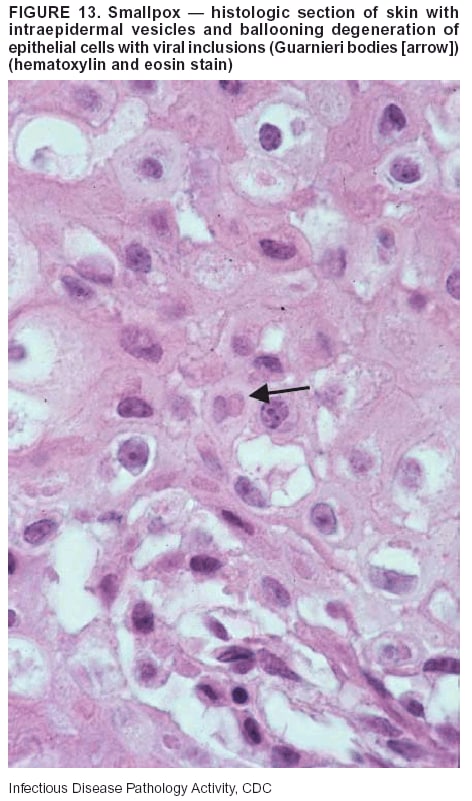

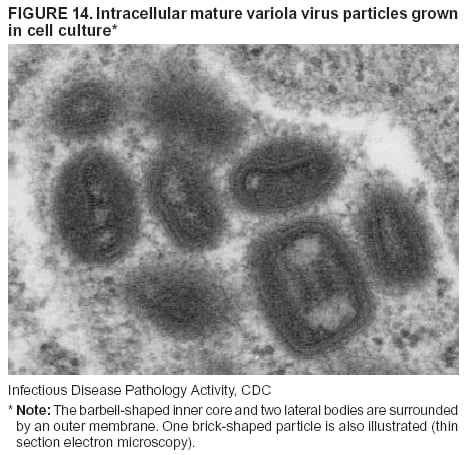

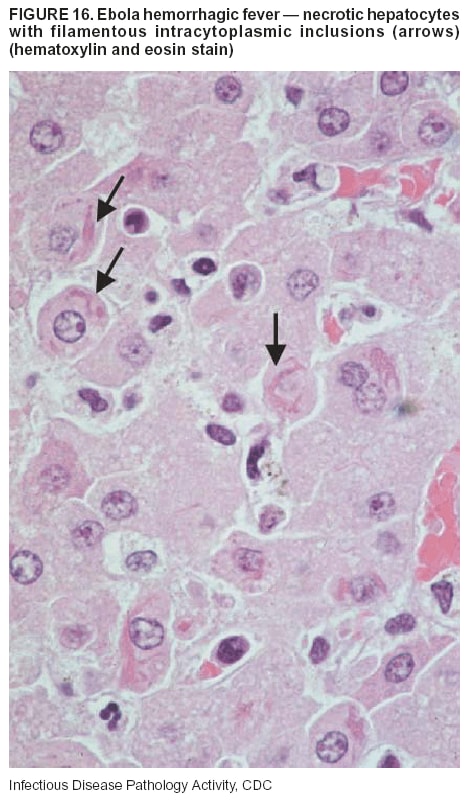

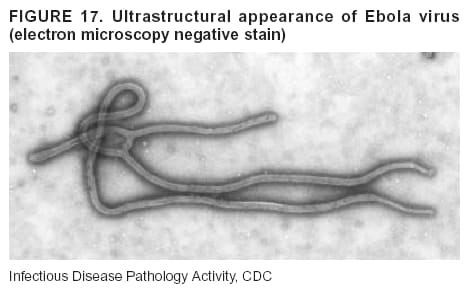

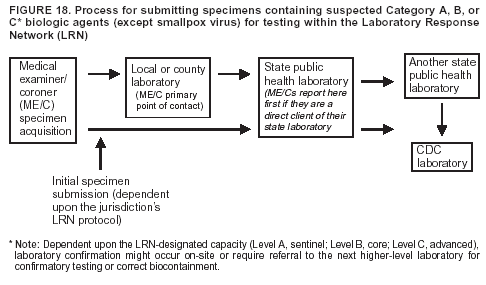

BackgroundMedicolegal Death InvestigatorsCDC has identified medicolegal death investigators (i.e., ME/Cs) as essential partners in terrorism preparedness and response (1). This report is designed to assist ME/Cs and their public health partners in developing appropriate capacity for recognizing and responding to deaths that are potentially a consequence of biologic terrorism. The organization of medicolegal death investigative systems within the United States varies by state (2). As ME/Cs and public health and public safety departments prepare to respond to terrorism-associated events, each state should consider how its medicolegal death investigation system is organized. These systems can be medical examiner-based (21 states and the District of Columbia), coroner-based (10 states), or both (19 states) (Figure 1). Typically, coroners are elected lay persons who use medical personnel to assist in death investigation and autopsy performance. Medical examiners are usually appointed physicians and pathologists who have received special training in death investigation and forensic pathology. Medicolegal death investigation systems can be either centralized (i.e., investigations emanate from one state-level office) or decentralized (i.e., investigations are conducted in more than one regional-, county-, or city-based office). A total of 23 states plus the District of Columbia have centralized systems; 27 states are decentralized. States with medical examiner systems might have a state-based medical examiner office, and also have county-level autonomous medical examiner offices that perform their own autopsies and manage their own data and administrative systems. ME/C offices can also vary in their organizational position within the government. ME/C offices might be a component of the public health department or the public safety department, or be independent of other government agencies. All types of medicolegal death investigation systems should be considered when determining the roles, responsibilities, and participation of ME/Cs in a jurisdiction's terrorism preparedness and response plans. Biologic TerrorismBiologic terrorism is defined as "the use or threatened use of biologic agents against a person, group, or larger population to create fear or illnesses for purposes of intimidation, gaining an advantage, interruption of normal activities, or ideologic activities. The resultant reaction is dependent upon the actual event and the population involved and can vary from a minimal effect to disruption of ongoing activities and emotional reaction, illness, or death" (3). In the United States in 1984, an outbreak of terrorism-related Salmonella dysentery caused 715 persons to become ill, but no fatalities resulted (4). In 2001, the intentional distribution of anthrax spores through the U.S. Postal Service resulted in five deaths from inhalational anthrax (5--8). MEs were critical members of the response team during the anthrax outbreak, performing autopsies on each fatality to confirm the cause of death as anthrax and to identify the manner of death as homicide. ME/Cs have state statutory authority to investigate deaths that are sudden, suspicious, violent, unattended, or unexplained (9); therefore, these investigators have a role in recognizing and reporting fatal outbreaks, including those that are possibly terrorism-related, and a role in responding to a known terrorist event (10--12). Deaths of persons at home or away from health-care facilities fall under the jurisdiction and surveillance of medicolegal death investigators (13), who often identify infectious diseases that are not terrorism-related. For example, in 1993, MEs recognized an outbreak of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, a disease with symptoms that can mimic terrorism-related illnesses (14). Deaths of patients in hospitals can also fall under medicolegal jurisdiction if the patient dies precipitously before an accurate diagnosis is made or if a public health concern exists (10). Fatalities caused by known terrorist events are homicides and therefore fall under the statutory jurisdiction of ME/Cs. Risk assessment for potential biologic terrorism is an uncertain process. Hypothetical terrorism scenarios can involve a limited number of cases or millions of cases, with proportionate numbers of fatalities. For example, in 2002, the Dark Winter smallpox exercise included in the scenario 3 million fourth-generation cases of smallpox and approximately 1 million deaths (15). In 2000, the TOPOFF (Top Officials) plague exercise included in the scenario 2,000 fatalities in a 1-week period (16). Given such possibilities if a biologic terrorist event occurred, ME/Cs should proactively identify appropriate resources and links to the public health, emergency response, health-care, and law enforcement communities. With appropriate resources and links, ME/Cs can assist with surveillance for infectious disease deaths possibly caused by terrorism and provide confirmatory diagnoses and evidence in deaths clearly linked to terrorism. Conversely, public health agencies should recognize ME/Cs as a vital part of the public health system and keep them informed of infectious disease outbreaks occurring in their jurisdictions so that they are better able to recognize related fatalities. Additionally, public health agencies should provide ME/Cs with appropriate resources to enhance their surveillance and response capacities for terrorism. An ME/C's principal diagnostic tool is the autopsy. This procedure enables pathologists to identify the dead, observe the condition of the body, and reach conclusions regarding the cause and manner of death. Autopsies are valuable in diagnosing unrecognized infections, evaluating therapy, understanding the pathogenesis and route of infection for uncommon or emerging infections, and developing evidence for subsequent legal proceedings (10,17). In 1979, an anthrax outbreak occurred that was associated with an unintentional release of spores from a bioweapons factory in the Soviet city of Sverdlovsk; pathologists used autopsies to identify the cause of death as anthrax and the route of infection as inhalation (18). In a 1945 smallpox outbreak, autopsy pathologists, rather than clinicians, were the physicians who recognized the sentinel case (19). Probable Biologic Terrorism Agents, Diseases, and Diagnostic TestsAgent CategoriesIn this report, the list of potential biologic terrorism agents has been prioritized on the basis of the risk to national security (Box 1) (1). Biologic agents are classified as high-risk, or Category A, because they can 1) be easily disseminated or transmitted person to person; 2) cause high mortality, with potential for major public health impact; 3) might cause public panic and social disruption; or 4) require special action for public health preparedness. The second highest priority, or Category B, agents include those that 1) are moderately easy to disseminate; 2) cause moderate morbidity and low mortality; or 3) require enhanced disease surveillance. The third highest priority, or Category C, agents include emerging pathogens that can be engineered for future mass dissemination because of 1) availability; 2) ease of production and dissemination; or 3) potential for high morbidity and mortality and major health impact. Recognizing pathologic features of different biologic agents is important, as demonstrated by the inhalational and cutaneous anthrax cases that occurred in the United States during 2001 (5,8,20--23). The autopsy of the index patient was performed to determine how the person had acquired anthrax (cutaneous, gastrointestinal, or inhalational). After inhalational anthrax was diagnosed, public health officials were able to better define potential sources of the airborne Bacillus anthracis spores. Diagnostic TestsIf possible, given the constraints of case volume and biosafety concerns, complete autopsies with histologic sampling of multiple organs should be performed in deaths potentially caused by infections with biologic terrorism agents. Autopsy diagnostic procedures for the Category A agents include microscopic examination, combined with the collection of specimens for additional tests that will aid in determining a definitive organism-specific diagnosis. Blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and tissue samples or swabs should be placed in transport media that will allow bacterial and viral isolation. Serum should be collected for serologic and biologic assays. Tissue samples should be frozen for polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Tissue samples should also be placed in electron microscopy fixative (glutaraldehyde). Microscopic examination of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) is essential to characterizing the patterns of tissue damage defining a syndrome and establishes a list of possible microorganisms in the differential diagnosis. To enhance surveillance for these conditions, a matrix of potential pathology-based syndromes (Table 1) has been developed to guide autopsy pathologists in recognizing potential cases (24). Special stains (e.g., tissue Gram and silver impregnation stains [Steiner's or Warthin-Starry]), can be helpful in identifying bacterial agents. Additionally, specific immunohistochemical (IHC) and direct fluorescent assays (DFA) for the Category A terrorism agents have been developed and are available at CDC.† These tests can be performed on formalin-fixed tissues. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of the Category A agents and corresponding diagnostic methods are summarized in this report (Tables 2 and 3). AnthraxAgent: Bacillus anthracis Pathologic Findings. Anthrax has three pathologic forms. Cutaneous anthrax is characterized by an eschar that forms where the bacteria entered the skin (Figure 2). Microscopically, the epidermis has necrosis and crusts, whereas the dermis demonstrates necrosis, edema, hemorrhage, perivascular inflammation, and vasculitis. The lymph nodes that drain the skin site eventually become enlarged, necrotic, and hemorrhagic. Gastrointestinal anthrax is distinguishable by hemorrhagic ulcers in the terminal ileum and caecum accompanied by mesenteric hemorrhagic lymphadenitis and peritonitis. Inhalational anthrax is characterized by hemorrhagic mediastinal lymphadenitis (Figure 3) accompanied by pleural effusions. Histologically, lymph nodes have abundant edema, hemorrhage, and necrosis with limited inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 4) (18,25--29). As any of the three anthrax forms progresses, the bacteria can spread to abdominal organs, producing petechial hemorrhages, and to the central nervous system, producing hemorrhagic meningitis (i.e., cardinal's cap) (Figure 5). Diagnostic Specimens. Performing a complete autopsy with histologic sampling of multiple organs will help determine the distribution of bacilli and the portal of entry. The specimens that harbor the highest number of B. anthracis organisms vary by the pathologic form of anthrax. For example, diagnosis of cutaneous anthrax requires skin samples from the center and periphery of the eschar, whereas for inhalational anthrax, pleural fluid cell blocks, pleura tissue, and mediastinal lymph nodes have the highest amounts of bacilli and antigens. Diagnostic Tests. If the patient has not received antibiotics, bacilli can be observed in tissues with H&E, Gram, and silver impregnation stains and IHC assays (Figures 6 and 7). However, after antibiotic treatment has been instituted, only silver stains and IHC assays will highlight the bacilli. IHC assays for B. anthracis can demonstrate bacilli, bacillary fragments, and granular bacterial fragments in formalin-fixed tissues, even after 10 days of antibiotic treatment. Although a DFA test is available for B. anthracis, it is not used on formalin-fixed tissues. PlagueAgent: Yersinia pestis Pathologic Findings. Similar to anthrax, the clinicopathologic manifestations of plague are classified on the basis of the portal of entry of Y. pestis. Bubonic plague refers to an acute lymphadenitis that occurs after the bacteria have penetrated the skin (Figure 8). Usually, skin lesions are inconspicuous or have a small vesicle or pustule that might not be evident at the time the infected lymph node (bubo) appears. Histologically, the bubo exhibits edema, hemorrhage, necrosis, and a ground-glass amphophilic material that represents masses of bacilli. Primary pneumonic plague refers to the infection caused by inhalation of airborne bacteria, producing intra-alveolar edema accompanied by varying amounts of acute inflammatory infiltrate and abundant bacteria. Primary septicemic plague occurs when Y. pestis enters through the oropharyngeal route. In septicemic plague, the cervical lymph nodes draining the infected region will display the previously described pathologic features. As the disease progresses, bacteria are distributed widely throughout the body, and findings consistent with shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation are observed. Septicemic plague with bacterial seeding of the lungs results in secondary pneumonic plague (Figure 9, left [A]) (30--35). Diagnostic Specimens. Performing a complete autopsy with histologic sampling of multiple organs will help determine the distribution of bacteria and the portal of entry. Enlarged, soft, hemorrhagic lymph nodes should be sampled and tested for Y. pestis. The lungs should be sampled to determine whether a primary or secondary infection existed (30). Diagnostic Tests. Y. pestis can be visualized in formalin-fixed tissues by using H&E, Gram, silver impregnation, and Giemsa stains; however, specific identification of the bacilli in tissues can only be performed by using IHC or DFA (Figure 9, right [B]). TularemiaAgent: Francisella tularensis Pathologic Findings. Tularemia can also have multiple clinicopathologic forms, depending on the portal of entry, including ulceroglandular, oculoglandular, glandular, pharyngeal, typhoidal, and pneumonic. In all forms, the primary draining lymph nodes demonstrate necrotizing lymphadenitis surrounded by a neutrophilic and granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate. In the ulceroglandular form, a skin ulcer or eschar with corresponding lymph node involvement is present, but skin lesions are absent in the glandular form. In the oculoglandular form, the eye exhibits conjunctivitis with ulcers and soft-tissue edema. The pharyngeal form is characterized by pharyngitis or tonsillitis with ulceration. The lungs in pneumonic tularemia exhibit abundant fibrinous necrosis accompanied by varying amounts of mixed inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 10, left [A]). Typhoidal tularemia refers to systemic involvement with focal areas of necrosis in the major organs and disseminated intravascular coagulation, but lacks a group of primary draining lymph nodes (36--40). In cases of tularemia sepsis, organisms can be seen with blood smears (Figure 11). Diagnostic Specimens. Performing a complete autopsy with histologic sampling of multiple organs will help determine the distribution of bacteria and the portal of entry. Enlarged, necrotic lymph nodes should be sampled and tested for F. tularensis. Culture swabs from the potential portals of entry (e.g., skin, conjunctiva, or throat) can be useful. Diagnostic Tests. The microorganisms are difficult to demonstrate with special stains; however, IHC and DFA have been successfully used in formalin-fixed tissues to demonstrate the bacteria (Figure 10, right [B]). BotulismAgent: Absorption of Clostridium botulinum Toxin Pathologic Findings. C. botulinum elaborates a potent, preformed neurotoxin. The most important diagnostic feature of botulism is the clinical history because the histopathologic changes are nonspecific (e.g., central nervous system hyperemia and microthrombosis of small vessels) (41). Diagnostic Specimens. When botulism is suspected because of a symmetrical, descending pattern of weakness and paralysis of cranial nerves, limbs, and trunk, the pathologist should obtain tissue for anaerobic cultures from the suspect entry sites (i.e., wound, gastrointestinal tract, or respiratory tract) and serum for botulinum toxin mouse bioassay. Diagnostic Tests. Microbiologic culture and botulinum toxin mouse bioassay with serum are necessary. SmallpoxAgent: Variola virus (Orthopoxvirus) Pathologic Findings. Smallpox is an acute, highly contagious illness caused by a member of the Poxviridae family. Variola major refers to the form with a higher mortality rate, and variola minor or alastrim is a milder form. The lesions develop at approximately the same time and rate, starting in the palms and soles and spreading centrally; they first appear as macules and papules, and then progress to vesicles and umbilicated pustules (Figure 12), followed by scabs and crusts, and end as pitted scars. Occasionally, a hemorrhagic and uniformly fatal form occurs. This form has extensive bleeding into the skin and gastrointestinal tract and can be grossly taken for meningococcemia, acute leukemia, or a drug reaction (42). Microscopically, the skin exhibits multiloculated, intraepidermal vesicles; ballooning degeneration of epithelial cells; intracytoplasmic, paranuclear, and eosinophilic viral inclusions (i.e., Guarnieri bodies) (Figure 13); and occasionally intranuclear viral changes. Secondary infections (e.g., bronchitis, pneumonia, and encephalitis) can complicate the clinical appearance (43--48). Diagnostic Specimens. Cutaneous lesions are the most important sample for smallpox. Samples should include fluid from vesicles to be studied by electron microscopy, and skin samples fixed in formalin for histopathology and immunohistochemistry. Performing a complete autopsy with histologic sampling of multiple organs will help determine the extent and distribution of the virus, as well as the occurrence of secondary infections. Diagnostic Tests. Electron microscopic studies of vesicle fluid or skin samples can identify characteristic viral particles (Figure 14). IHC studies have demonstrated the virus in the epithelial cells and in the subjacent fibroconnective tissue. Viral Hemorrhagic FeversAgents: Multiple Viruses that can cause hemorrhagic fevers belong to different families, including Filoviridae (Ebola, Marburg viruses), Flaviviridae (yellow fever, dengue viruses), Bunyaviridae (Rift Valley fever, Crimean Congo, Hantaan, Sin Nombre viruses), and Arenaviridae (Junin, Machupo, Guanarito, Lassa viruses). Pathologic Findings. The term viral hemorrhagic fever is reserved for febrile illnesses associated with abnormal vascular regulation and vascular damage. Common pathologic findings at autopsy include petechial hemorrhages and ecchymoses of skin (Figure 15), mucous membranes, and internal organs. Although systemic hemorrhages occur in the majority of viral hemorrhagic fevers, certain agents infect specific cells and thus histopathologic features can differ among agents. Necrosis of liver and lymphoid tissues, as well as diffuse alveolar damage, occur in the majority of viral hemorrhagic fevers, but can be more prominent for certain infections (e.g., midzonal hepatocellular necrosis is prominent in yellow fever, but not in dengue). Viral inclusions can be visualized in hepatocytes with Ebola or Marburg infections by using light and electron microscopy (Figure 16) (49--54). Diagnostic Specimens. Performing a complete autopsy with histologic sampling of multiple organs can determine the extent of the disease and help identify the specific virus. After a specific etiologic agent has been isolated or identified from an index case, targeted sampling of additional cases with similar symptoms can decrease the exposure of autopsy personnel to these hazardous agents and still yield diagnostic material. For example, during outbreaks of Ebola hemorrhagic fever in Africa, using IHC on skin punch biopsy samples was sufficient to provide a diagnosis in a substantial number of fatalities and minimized the risk to the medical personnel who obtained the specimens (49). Diagnostic Tests. Serum and skin samples can be tested by using PCR, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy (Figure 17). Additionally, serum can be inoculated into experimental animals or culture cells for viral isolation. Laboratory Response NetworkCDC, in collaboration with the Association of Public Health Laboratories (APHL), the FBI, and other federal agencies, has developed the Laboratory Response Network (LRN) as a multilevel system of linked local, state, and federal public health laboratories as well as veterinary, food, and environmental laboratory partners (55--57). The primary components of LRN are the state public health laboratories representing each of the 50 states. Within certain states, laboratories are located in different counties and more populated cities. In addition, federal laboratories within LRN include CDC, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID), and other Department of Defense laboratories. Each laboratory has been assigned a designation (Table 4), predicated on their diagnostic capability, ranging from sentinel status (i.e., Level A for presumptive-level screening) through national laboratory status (i.e., Level D for genetic subtyping and confirmatory testing) (55--57). Hospital clinical laboratories are designated as sentinel laboratories (Level A); they have a rapid rule out and forward mission when handling presumptive clinical cases. County, city, and state public health laboratories are designated as confirmatory reference facilities (Level B, core, or Level C, advanced), depending on their degree of containment capacity and technical proficiency in performing agent-specific confirmatory analyses and rapid presumptive testing by PCR for nucleic acid amplification and time-resolved fluorescence for antigen detection. The Level D designation is reserved for CDC and USAMRIID laboratories. No regional laboratories exist; the network functions by channeling the specimens through the designated levels to a pathogen-specific conclusion. ME/Cs should submit specimens from suspected biologic terrorism-related cases to the state public health laboratory through the local or county laboratory that serves their jurisdiction, unless their standard reporting protocol makes them a direct client of the state laboratory. These primary laboratories conduct the tests that fall within the scope of their ability and refer specimens to the state laboratory for more advanced tests. The state laboratory processes and refers specimens in a similar manner to other state laboratories or CDC (Figure 18). Contact information for all state diagnostic laboratories is included in this report (Appendix A). The point of contact for ME/Cs should remain the laboratory where the specimens were first submitted, unless they are directed to contact a reference laboratory (e.g., a state laboratory) to track the progress of the testing. Before the need for LRN services arises, ME/Cs should establish contact with the public health laboratory serving their jurisdiction and determine how the laboratory services can be best accessed when needed. Such a relationship might require a memorandum-of-understanding, which should be prepared and agreed to in advance. All specimens that are to be tested for potential biologic terrorism pathogens are handled through the same reporting and submission process except specimens potentially containing smallpox virus. Because smallpox virus should only be handled in a Biosafety Level 4 facility, the specimen should be transported to CDC (57). If ME/Cs suspect this agent, they should notify their state public health department, which can test for other agents that cause a vesiculopustular rash (i.e., varicella zoster, vaccinia, and monkeypox viruses) and either further test or refer the specimen for rapid presumptive screening for smallpox virus by PCR. The same laboratories will be able to coordinate submission of the specimen to CDC as needed for pathogen confirmation. In advance, ME/Cs should establish contact with the state health department representative who would coordinate smallpox specimen submission. In their surveillance capacity and concurrent with specimen submission, ME/Cs should notify the epidemiologic investigation unit in their local or state health department of the suspected smallpox-infected decedent. Biosafety ConcernsAutopsy RisksBiosafety is critical for autopsy personnel who might handle human remains contaminated with biologic terrorism agents. Tularemia, viral hemorrhagic fevers, smallpox, glanders, and Q fever have been transmitted to persons performing autopsies (i.e., prosectors); certain infections have been fatal (49,58--70). Infections can be transmitted at autopsies by percutaneous inoculation (i.e., injury), splashes to unprotected mucosa, and inhalation of infectious aerosols (71). All of the Category A pathogens are potentially transmissible to autopsy personnel, although the degree of risk varies considerably among these organisms. Additionally, autopsies of persons who die as the result of terrorism-related infections might expose autopsy personnel to residual surface contamination with infectious material. For example, botulinum toxin has the potential to be inhaled by autopsy personnel if it is present on the body surface at the time of examination (72). Heavy surface contamination of the body is unlikely because of the incubation period for the majority of infectious agents and the likelihood that a victim will have bathed and changed clothes after exposure and before becoming symptomatic and dying (73). However, if such residual material (e.g., powder) is present, examination and specimen collection should be undertaken by using appropriate biosafety procedures to protect autopsy and analytic laboratory personnel from possible exposure to more concentrated infectious material. Because human remains infected with unidentified biologic terrorism pathogens might arrive at autopsy without warning, basic protective measures described in this report should be maintained for all contact with potentially infectious materials (74,75). In addition to these measures, certain high-risk activities (e.g., use of oscillating saw) are known to increase the potential for worker exposure and should be performed with added safety precautions. Autopsy PrecautionsExisting guidelines for biosafety and infection control for patient care are designed to prevent transmission of infections from living patients to care providers, or from laboratory specimens to laboratory technicians (76,77). Although certain biosafety and infection-control guidelines are applicable to the handling of human remains, inherent differences exist in transmission mechanisms and intensity of potential exposures during autopsies that require specific consideration (71). As with any contact involving broken skin or body fluids when caring for live patients, certain precautions must be applied to all contact with human remains, regardless of known or suspected infectivity. Even if a pathogen of concern has been ruled out, other unsuspected agents might be present. Thus, all human autopsies must be performed in an appropriate autopsy room with adequate air exchange by personnel wearing appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) (71). All autopsy facilities should have written biosafety policies and procedures; autopsy personnel should receive training in these policies and procedures, and the annual occurrence of training should be documented. Standard Precautions are the combination of PPE and procedures used to reduce transmission of all pathogens from moist body substances to personnel or patients (77). These precautions are driven by the nature of an interaction (e.g., possibility of splashing or potential of soiling garments) rather than the nature of a pathogen. In addition, transmission-based precautions are applied for known or suspected pathogens. Precautions include the following:

All autopsies involve exposure to blood, a risk of being splashed or splattered, and a risk of percutaneous injury (71). The propensity of postmortem procedures to cause gross soiling of the immediate environment also requires use of effective containment strategies. All autopsies generate aerosols; furthermore, postmortem procedures that require using devices (e.g., oscillating saws) that generate fine aerosols can create airborne particles that contain infectious pathogens not normally transmitted by the airborne route (71,78--81). PPE For autopsies, Standard Precautions can be summarized as using a surgical scrub suit, surgical cap, impervious gown or apron with full sleeve coverage, a form of eye protection (e.g., goggles or face shield), shoe covers, and double surgical gloves with an interposed layer of cut-proof synthetic mesh (71). Surgical masks protect the nose and mouth from splashes of body fluids (i.e., droplets >5 µm); they do not provide protection from airborne pathogens (82,83). Because of the fine aerosols generated at autopsy, prosectors should at a minimum wear N-95 respirators for all autopsies, regardless of suspected or known pathogens (84). However, because of the efficient generation of high concentration aerosols by mechanical devices in the autopsy setting, powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs) equipped with N-95 or high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters should be considered (85--87). Autopsy personnel who cannot wear N-95 respirators because of facial hair or other fit limitations should wear PAPRs. Autopsy Procedures Standard safety practices to prevent injury from sharp items should be followed at all times (77). These include never recapping, bending, or cutting needles, and ensuring that appropriate puncture-resistant sharps disposal containers are available. These containers should be placed as close as possible to where sharp items are used to minimize the distance a sharp item is carried. Filled sharps disposal containers should be discarded and replaced regularly and never overfilled (77). Protective outer garments should be removed when leaving the immediate autopsy area and discarded in appropriate laundry or waste receptacles, either in an antechamber to the autopsy suite or immediately inside the entrance if an antechamber is unavailable. Handwashing is requisite upon glove removal (77). Engineering Strategies and Facility Design Concerns Air-handling systems for autopsy suites should ensure both adequate air exchanges per hour and correct directionality and exhaust of airflow. Autopsy suites should have a minimum of 12 air exchanges/hour and should be at a negative pressure relative to adjacent passageways and office spaces (84). Air should never be returned to the building interior, but should be exhausted outdoors, away from areas of human traffic or gathering spaces (e.g., air should be directed off the roof) and away from other air intake systems (88,89). For autopsies, local airflow control (i.e., laminar flow systems) can be used to direct aerosols away from personnel; however, this safety feature does not eliminate the need for appropriate PPE. Clean sinks and safety equipment should be positioned so that they do not require unnecessary travel to reach during routine work and are readily available in the event of an emergency. Work surfaces should have integral waste-containment and drainage features that minimize spills of body fluids and wastewater. Biosafety cabinets should be available for handling and examination of smaller infectious specimens; however, the majority of available cabinets are not designed to contain a whole body (76,90). Oscillating saws are available with vacuum shrouds to reduce the amount of particulate and droplet aerosols generated (80). These devices should be used whenever possible to decrease the risk of dispersing aerosols that might lead to occupationally acquired infection. Vaccination and Postexposure Prophylaxis Vaccines are available that convey protection against certain diseases considered to be potentially terrorism-associated, including anthrax, plague, and tularemia (76). However, these vaccines are not recommended for unexposed autopsy workers at low risk. Consistent application of standard safety practices should obviate the need for vaccination for B. anthracis and Y. pestis. In 2003, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) initiated a program to administer vaccinia (smallpox) vaccine to first responders and medical personnel. In this context, persons who might be called on to assess remains or specimens from patients with smallpox should be included among this group (91) (Box 2). The administration of prophylactic antibiotics to autopsy workers exposed to potentially lethal bacterial pathogens is sometimes appropriate. For example, autopsy personnel exposed to Y. pestis aerosols should consider receiving such treatment regardless of vaccination status (92). Similarly, because tularemia can result from infection with a limited number of organisms, an exposure to F. tularensis should also prompt consideration of antimicrobial prophylaxis. However, decisions to use antimicrobial postexposure prophylaxis should be made in consultation with infectious disease and occupational health specialists, with consideration made of vaccination status, nature of exposure, and safety and efficacy of prophylaxis. Decontamination of Body-Surface Contaminants If human remains with heavy, residual surface contamination (i.e., visible) must be assessed, they should be cleansed before being brought to the autopsy facility and after appropriate samples have been collected in the field. Surface cleaning should be performed with an appropriate cleaning solution (e.g., 0.5% hypochlorite solution or phenolic disinfectant) used according to manufacturer's instructions. If the number of remains requiring autopsy is limited (i.e., one or two), cleaning of heavily contaminated remains can be undertaken in an autopsy facility that has the infrastructure, capacity, and hazardous materials (HAZMAT)-trained personnel to perform the cleaning safely. Heavily contaminated remains should not be brought to facilities where patient care is performed. Both personnel carrying contaminated remains and personnel occupying areas through which remains are being carried should wear PPE. HAZMAT personnel should perform large-scale decontamination outdoors in a controlled setting. To ensure mutual understanding of the roles and responsibilities of HAZMAT and death-investigation personnel in situations with contaminated remains, ME/Cs should develop response protocols with HAZMAT personnel before such an event occurs. Waste Handling Liquid waste (e.g., body fluids) can be flushed or washed down ordinary sanitary drains without special procedures. Pretreatment of liquid waste is not required and might damage sewage treatment systems. If substantial volumes are expected, the local wastewater treatment personnel should be consulted in advance. Solid waste should be appropriately contained in biohazard or sharps containers and incinerated in a medical waste incinerator (73,75). Storage and Disposition of Corpses The majority of potential biologic terrorism agents (B. anthracis, Y. pestis, or botulinum toxin) are unlikely to be transmitted to personnel engaged in the nonautopsy handling of a contaminated cadaver. However, such agents as the hemorrhagic fever viruses and smallpox virus can be transmitted in this manner. Therefore, Standard Precautions (77) should be followed while handling all cadavers before and after autopsy. When bodies are bagged at the scene of death, surface decontamination of the corpse-containing body bags is required before transport. Bodies can be transported and stored (refrigerated) in impermeable bags (double-bagging is preferable), after wiping visible soiling on outer bag surfaces with 0.5% hypochlorite solution. Storage areas should be negatively pressured with 9--12 air exchanges/hour. The risks of occupational exposure to biologic terrorism agents while embalming outweigh its advantages; therefore, bodies infected with these agents should not be embalmed. Bodies infected with such agents as Y. pestis or F. tularensis can be directly buried without embalming. However, such agents as B. anthracis produce spores that can be long-lasting and, in such cases, cremation is the preferred disposition method. Similarly, bodies contaminated with highly infectious agents (e.g., smallpox and hemorrhagic fever viruses) should be cremated without embalming. If cremation is not an option, the body should be properly secured in a sealed container (e.g., a Zigler case or other hermetically sealed casket) to reduce the potential risk of pathogen transmission. However, sealed containers still have the potential to leak or lose integrity, especially if they are dropped or are transported to a different altitude (93). ME/Cs should work with local emergency management agencies, funeral directors, and the state and local health departments to determine, in advance, the local capacity (bodies per day) of existing crematoriums, and soil and water table characteristics that might affect interment. For planning purposes, a thorough cremation produces approximately 3--6 pounds of ash and fragments. ME/Cs should also work with local emergency management agencies to identify sources and costs of special equipment (e.g., air curtain incinerators, which are capable of high-volume cremation) and the newer plasma incinerators, which are faster and more efficient than previous incineration methods. The costs of such equipment and the time required to obtain them on request should be included in state and local terrorism preparedness plans. ME/C's Role in Biologic Terrorism SurveillanceME/Cs should be a key component of population-based surveillance for biologic terrorism. They see fatalities among persons who have not been examined initially by other physicians, emergency departments, or hospitals. In addition, persons who have been seen first by other health-care providers might die precipitously, without a confirmed diagnosis, and therefore fall under medicolegal jurisdiction. Autopsies are a critical component of surveillance for fatal infectious diseases, because they provide organism-specific diagnoses and clarify the route of exposure (94). With biologic terrorism-related fatalities, organisms identified in autopsy tissues can be characterized by strain to assist in the process of criminal attribution. Models for ME surveillance for biologic terrorism mortality include sharing of daily case dockets with public health authorities (e.g., King County, Washington, and an active symptom-driven case acquisition and pathology syndrome-based public health reporting system developed in New Mexico [24]). Different areas of responsibility exist for ME/Cs regarding their role in effective surveillance for possible terrorism events. The following steps should be taken in local jurisdictions to enable ME/Cs to implement biologic terrorism surveillance:

ME/C's Role in Data Collection, Analysis, and DisseminationFor public health surveillance, criminal justice, and administrative purposes, ME/Cs should promptly, accurately, and thoroughly collect, document, electronically store, and have available for analysis and reporting, case-specific death-investigation information. Initially, depending upon local resources and legal restrictions, all aspects of data management and use might not need to occur in-house. Recognizing that numerous entities use medicolegal death-investigation data, ME/Cs should establish collaborations with public health and law enforcement professionals to achieve the goal of complete, accurate, and timely case-specific death-investigation data. Advance planning and policy development should also clarify to whom such data may be released and under which circumstances. To facilitate this process, the following steps should be taken:

Jurisdictional, Evidentiary, and Operational ConcernsFederal RoleOn February 28, 2003, Homeland Security Presidential Directive 5 (HSPD-5) modified federal response policy (97). Under the new directive, the Secretary of Homeland Security is the principal federal official for domestic incident management. Pursuant to the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (Public Law 107-296), the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is responsible for coordinating federal operations within the United States to prepare for, respond to, and recover from terrorist attacks, major disasters, and other emergencies. The Secretary will coordinate the federal government's resources used in response to or recovery from terrorist attacks, major disasters, or other emergencies if and when any one of the following four conditions applies: 1) a federal department or agency acting under its own authority has requested the assistance of the Secretary; 2) the resources of state and local authorities are overwhelmed and federal assistance has been requested by the appropriate state and local authorities; 3) more than one federal department or agency has become substantially involved in responding to the incident; or 4) the Secretary has been directed to assume responsibility for managing the domestic incident by the President. HSPD-5 further stipulates that the U.S. Attorney General, through the FBI, has lead federal responsibility for criminal investigations of terrorist acts or terrorist threats by persons or groups inside the United States, or directed at U.S. citizens or institutions abroad, where such acts are within the federal criminal jurisdiction of the United States. The FBI, in cooperation with other federal departments and agencies engaged in activities to protect national security, will also coordinate the activities of the other members of the law enforcement community to detect, prevent, preempt, and disrupt terrorist attacks against the United States. In the event of a weapons of mass destruction (WMD) threat or incident, the local FBI field office special agent in charge (SAC) will be responsible for leading the federal criminal investigation and law enforcement actions, acting in concert with the principal federal officer (PFO) appointed by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and state and local officials. The FBI has a WMD coordinator in each of the agency's 56 field offices (Appendix B). These persons are responsible for pre-event planning and preparedness, as well as responding to WMD threats or incidents. ME/Cs are encouraged to contact their local FBI WMD coordinator before an incident to clarify roles and responsibilities, and ME/Cs should contact the coordinator in any case where concerns or suspicions exist of a potential WMD-related death. The FBI assertion of jurisdiction at the scene of a terrorist event would not necessarily usurp (or relieve) ME/Cs from their statutory authority and responsibility to identify decedents and determine cause and manner of death. Such an arrangement is consistent with the performance of medicolegal death investigation where other federal crimes are involved. ME/Cs who conduct terrorism-associated death investigations should be prepared to present their medicolegal death investigation findings in federal court. Public Health Agency AuthorityState public health laws might establish the health department's specific authority to control certain aspects of operations, personnel, or corpses in a public health emergency. For example, the Center for Law and the Public's Health at Georgetown and Johns Hopkins Universities, at the request of CDC, has created a model state emergency health powers act for adoption by states (98). Different states have either enacted versions of this act or are in the process of introducing similar legislative bills (99). ME/Cs should know specifically how existing state laws might provide for the health department to take control and dictate the disposition of human remains (burial or cremation). A state's emergency health powers act might also provide for

ME/Cs and health departments should work together as part of the emergency planning process to determine which emergency health powers might be established by the health department and under what circumstances these might be invoked for each potential biologic terrorism agent. Determining how health departments and ME/C operations can best interact, including documenting concerns regarding the availability of death-investigation personnel and the control and disposition of human remains, should be emphasized. ME/Cs should take part in community exercises to clarify and practice their role in the emergency response process. General OperationsIn the majority of terrorism-associated scenarios, ME/Cs are responsible for identifying remains and determining the cause and manner of death. To that end, ME/Cs might need to enlist additional local, state, or federal assistance while maintaining primary responsibility for death investigation. ME/Cs should request this assistance from the local or state emergency operations center (EOC), as appropriate. The probable source of federal assistance is the Disaster Mortuary Operational Response Team (DMORT). However, DMORT has not yet developed capacity to respond to events precipitated by the release of biologic agents (further details regarding DMORT and other federal agencies are discussed in following sections). Where possible, postmortem examinations for identifying remains and determining cause and manner of death should occur within the local or state jurisdiction where victims have died. Local resources dictate whether the statutory ME/C system can accomplish this with existing personnel and within existing facilities, or whether additional local, state, or federal assistance is necessary. Moving substantial numbers of human remains, particularly those contaminated by a biologic agent (known or unknown) to locations considerably distant from the scenes of death is neither feasible nor safe. Two potential strategies can be used to augment the biosafety capacity of local agencies having limited resources. One strategy would be to develop a mobile Biosafety Level 3 autopsy laboratory. Another strategy would be to develop regional Biosafety Level 3 autopsy centers that can handle cases from surrounding jurisdictions or states. A combination of the two approaches will probably achieve the best coverage of national needs. Postmortem Examinations and Evidence CollectionA large-scale biologic event might create more fatalities than combined local, state, and federal agencies can store and examine (15). Small or rural jurisdictions might be overwhelmed by a relatively limited number of fatalities, whereas larger state or city ME/C offices could conceivably process greater numbers of human remains. No formulas exist that can be used to determine in advance the autopsy rate and the extent of autopsy that might be needed. In the event of a biologic event, ME/Cs should perform complete autopsies on as many cases as feasible on the basis of case volume and biosafety risks. These autopsies should meet the standards that forensic pathologists usually meet for homicide cases. Conferring with the FBI and appropriate prosecutorial authorities early in the process will ensure that appropriate documentary and diagnostic maneuvers are employed that will support the criminal justice process. Similarly, interacting with public health authorities early in the death-investigation process should ensure that appropriate diagnostic evaluations are conducted to support the public health investigation and response. After the etiologic agent has been determined, certain (or all) other potentially related fatalities can be selectively sampled to confirm the presence of the organism in question. ME/Cs should coordinate the decision to transition from complete autopsies to more limited examinations with law enforcement and public health professionals. Selective sampling could include skin swabs and needle aspiration of blood or other body fluids, tissues for culture, or biopsies of a particular tissue or organ for histologic diagnostic tests (e.g., immunohistochemical procedures and electron microscopy). The required specimens from a limited autopsy and the diagnostic procedures employed will be dictated by the nature of the biologic agent. Guidelines for targeted organs or tissues for culture or analysis were discussed previously. As with all homicides, chain-of-custody for specimens should be maintained at all times. Whenever a complete autopsy is performed, the goals should be to 1) establish the disease process and the etiologic agent; 2) determine that the agent or disease is indeed the cause of death; and 3) reasonably rule out competing causes of death. When limited autopsies or external examinations are performed, ME/C personnel should

Forming a reasonably sound medical opinion regarding cause and manner of death can be accomplished with knowledge of the presenting syndrome and circumstantial events, external examination of the body, and testing of appropriate specimens to document the etiologic agent. For example, in a confirmed smallpox outbreak, identifying the deceased, externally examining the body and photographing the lesions, and obtaining samples from the lesions for culture or electron microscopy might be adequate. Biologic evidence obtained at autopsy can be sent to local or state health department laboratories, and other physical evidence can be sent to the usual crime laboratory, unless otherwise instructed by the FBI. Laboratories within LRN, as described previously, are responsible for coordinating the transfer of evidence or results to the FBI, U.S. Attorney General, or local and state legal authorities, as appropriate. Consistent with routine practice, ME/Cs should document all evidence transfers adequately. Cause and Manner of Death StatementsDeath certificates are not withheld from the public record, even when the cause of death is terrorism-related. The cause of death section should be used to fully explain the sequence of the cause of death (e.g., "hemorrhagic mediastinitis due to inhalational anthrax"). If death resulted from a terrorism event, the manner of death should be classified as homicide. The "how injury occurred" section on the death certificate should be completed, and it should reflect how the infectious agent was delivered to the victim (e.g., "victim of terrorism; inhaled anthrax spores delivered in mail envelope"). The place of injury should be the statement of where (i.e., geographic location) the agent was received. Reimbursement for Expenses and Potential Funding SourcesAdditional funding for ME/Cs might be needed for either preparedness or use during an actual biologic terrorism event. ME/Cs should prepare financially for potential future terrorist events that might be similar to the anthrax attacks of October--November 2001. In crisis situations, funding is retroactive but no less a concern. Preparedness funding can support multiple activities, including training of ME/Cs for large-scale terrorism events. Certain activities involving training of ME/Cs have occurred through DMORT, a program authorized by the DHHS Office of Emergency Preparedness to rapidly mobilize ME/Cs to respond to incidents of mass fatality. Preparedness funding can also support surveillance activities in ME/C offices. As part of the Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response cooperative agreements with state health departments, CDC has provided funding to New Mexico and other states that are pursuing ME/C surveillance systems as an enhancement to their traditional surveillance systems. The New Mexico Office of the Medical Investigator has been a recipient of this funding through the New Mexico Department of Health since the inception of the cooperative agreement program. This funding has supported development of specialized surveillance techniques for deaths caused by potential agents of biologic terrorism (24) and recognition of ME/Cs as a key resource for all phases --- early detection, case characterization, incident response and recovery --- of a public health emergency response. CDC encourages pursuit of this enhanced (ME/C) surveillance capacity through cooperative agreements with states, if the state has made adequate progress with other critical capacity goals. ME/Cs might obtain preparedness funding by integrating their response activities into the existing EOCs that have been established at selected state and county levels (integration of ME/C offices into this framework is discussed in Communications and the Incident Command System). When ME/C offices are integrated into the emergency response system, ME/Cs have an opportunity to make emergency management officials aware of ME/C emergency responsibilities and resource needs. The sources of funding for consequence management, including medicolegal death investigation, will depend on the scope of the terrorism event. In events with a limited number of deaths, funding for activities related to the detection and diagnosis might remain at the office level. Because terrorism deaths are homicides, these deaths will contribute to an office's jurisdictional workload, and future planning for preparedness funding should be considered. Certain ME/C offices are already a part of the local or state public health department or are already affiliated with an EOC. ME/C offices, health departments, and EOCs are strongly encouraged to forge links for effective preparedness and response and to participate in joint training exercises to maximize preparedness funding. In events with multiple deaths, a federal emergency might be declared. As long as ME/Cs' offices are officially working through the state or local EOC, certain expenses associated with the response (e.g., cost of diagnostic testing) can be submitted to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) for reimbursement. In the majority of localities, these requests for resources required for appropriate response during an event should be submitted through local emergency management agencies that are part of state and local EOCs. Costs will probably be covered by the agency that has jurisdiction over the disaster (e.g., FEMA). In cases where a presidential disaster declaration is made, testing costs, victim identification, mortuary services, and those services that are covered by the National Disaster Medical System (a mutual aid network that includes DHHS, the Department of Defense, and FEMA) (100) are reimbursable under Emergency Support Function 8 (Health and Medical) of the Federal Response Plan (FRP). Under FRP, FEMA covers 75% of reimbursement costs; the remaining 25% are covered by the state through emergency funds or in-kind reimbursement. FEMA also supports state emergency funds through the DHHS electronic payments management system. In an emergency, all requests for reimbursement flow from their point of origin, in this case from an ME/C, through the state EOC/emergency management agency, to FEMA.§ Before an event, ME/Cs should clarify the procedures to follow to ensure that they will be reimbursed for expenses incurred as part of their emergency response. DMORTDMORT is a national program that includes volunteers, divided into 10 regional teams responsible for supporting death investigation and mortuary services in federal emergency response situations involving natural disasters and mass fatalities associated with transportation accidents or terrorism. Team members are specialists from multiple forensic disciplines, funeral directors, law enforcement agents, and administrative support personnel. Each team represents a FEMA region. DMORT members are activated through DHS after mass fatalities or events involving multiple displaced human remains (e.g., a cemetery washout after a flood). The primary functions of DMORT include the identification of human remains, evidence recovery from the bodies, recovery of human remains from the scene, and assisting with operation of a family assistance center. Whenever possible, identification of the bodies is made by using commonly accepted scientific methods (e.g., fingerprint, dental, radiograph, or DNA comparisons). Upon activation, DMORT members are federal government employees. When DMORT is activated, representatives from DHS are also sent to manage the logistics of deployment. The FBI most commonly staffs the fingerprint section of the morgue. The Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory in Rockville, Maryland, has traditionally performed DNA analyses; the arrangements for this testing are negotiated separately with the local ME/C. After a request for DMORT assistance has been made, one of two Disaster Portable Morgue Units (DPMUs) and DMORT staff are sent to the disaster site. DPMUs contain specialized equipment and supplies, prestaged for deployment within hours to a disaster site. DPMUs include all of the equipment required for a functional basic morgue with designated workstations and prepackaged equipment and supplies. DPMUs can operate at Biosafety Level 2, but do not have the ventilatory capacity necessary to protect prosectors and other nearby persons from airborne pathogens. DPMUs also contain equipment for site search and recovery, pathology, anthropology, radiology, photography, and information resources, as well as office equipment, wheeled examination tables, water heaters, plumbing equipment, electrical distribution equipment, personal protective gear, and temporary partitions and supports. DPMUs do not have the materials required to support microbiologic sampling. When a DPMU is deployed, members of the DPMU team (i.e., a subset of DMORT) are sent to the destination to unload the DPMU equipment and establish and maintain the temporary morgue. Additional equipment is required locally after DMORT activation. At a minimum, this equipment includes a facility in which to house the morgue equipment, a forklift to move the DPMU equipment into the temporary morgue facility, and refrigerated trucks to hold human remains. ME/Cs can request DMORT response after a mass fatality or after an incident resulting in the displacement of a substantial number of human remains. ME/Cs should follow state protocols for DMORT requests. Typically, ME/Cs contact the state governor's office, which then requests DMORT from DHS.¶ The request should include an estimate of how many deaths occurred (if known), the condition of the bodies (if known), and the location of the incident. When deployed, DMORT supports ME/Cs in the jurisdiction where the incident occurred. All medicolegal death investigation records created by DMORT are given to ME/Cs at the end of the deployment, and ME/Cs are ultimately responsible for all of the identifications made and the documents created pertaining to the incident. DMORT-WMD TeamThe DMORT-WMD team is composed of national rather than regional volunteers. The primary focus of DMORT-WMD is decontamination of bodies when death results from exposure to chemicals or radiation. DMORT-WMD is developing resources to respond to a mass disaster resulting from biologic agents. However, this team might have difficulty in responding to such an event if the deaths occur in multiple locations. The major forensic disciplines (i.e., forensic dentistry, forensic anthropology, and forensic pathology) as well as funeral directors, law enforcement, criminalists, and administrative support persons are represented on the DMORT-WMD team. Members of DMORT-WMD undergo specialized training that focuses on chemical and radiologic decontamination of human remains. The DMORT-WMD unit has separate equipment, stored separately from the DPMU, including PPE (up to and including level A suits), decontamination tents, and equipment to gather contaminated water. DMORT-WMD teams are requested and deployed in the same manner as general DMORTs. Communications and the Incident Command SystemME/Cs are key members of the biologic terrorism detection and management response team in any community and should be integrated into the comprehensive communication plan during any terrorism-associated event. Routine and consistent communication among ME/Cs and local and state laboratories, public health departments, EOCs, communication centers, DMORT, and other agencies, is critical to the success of efficient and effective biologic terrorism surveillance, fatality management, and public health and criminal investigations. Planning for different emergency scenarios and participation in disaster response exercises are necessary to ensure effective response to a terrorism event. Each state and certain counties have some type of emergency operation center that has been organized to provide a coordinated response during a terrorism event. ME/Cs should verify their jurisdiction's EOC contact point and work with them periodically regarding concerns related to preparedness and response. All EOCs follow the Incident Command System (ICS) (100), an internationally recognized emergency management system that provides a coordinated response across organizations and jurisdictions. The ICS structure allows for individual EOC decision making and different information flow in each state. ME/Cs should determine how the EOC functions in their jurisdiction. Each ICS is composed of a managing authority that directs the response of health department, law enforcement, and emergency management officials during a planning exercise, emergency, or major disaster. In addition to assessing the incident and serving as the interagency contact, ICS also coordinates the response to information inquiries and the safety monitoring of assigned response personnel. The ICS organizational framework, includes planning, operations, logistics, and finance/administration sections (101). ME/Cs are most likely to participate in the operations team, which makes tactical decisions regarding the incident response and implements those activities defined in action plans. This team might also include public health, emergency communications, fire, law enforcement, EMS, and state emergency management agency staff. During a suspected terrorism event, ME/Cs should be responsible for the following actions to facilitate communication:

ConclusionME/Cs are essential public health partners for terrorism preparedness and response. Despite state and local differences in medicolegal death-investigation systems, these investigators have the statutory authority to investigate deaths that are sudden, suspicious, violent, and unattended, and consequently play a vital role in terrorism surveillance and response. Public health officials should work with ME/Cs to ensure that these investigators can assist with surveillance for infectious disease deaths possibly caused by terrorism and provide confirmatory diagnoses and evidence in deaths linked to terrorism. This process should involve an assessment of local ME/C standards for accepting jurisdiction of potential infectious disease deaths and performing autopsies, laboratory capacity for making organism-specific diagnoses, and autopsy biosafety capacity. Ideally, ME/Cs should

If biologic terrorism-related fatalities occur, ME/Cs are responsible for identifying remains and determining the cause and manner of death. Routine and consistent communication among ME/Cs and local and state laboratories, public health departments, EOCs, law enforcement, and other agencies is critical to the success of efficient and effective biologic terrorism surveillance, fatality management, and public health and criminal investigations. To prepare for this possibility, ME/Cs should

The majority of ME/C facilities do not have the capacity to perform autopsies at Biosafety Level 3 as a consequence of facility design features that are expensive to fix. In addition, DMORT does not have the capacity to respond to events precipitated by the release of biologic agents. These limitations might affect local, state, and national surveillance for infectious disease deaths of public health importance, including those deaths potentially caused by terrorism. Two potential strategies might be used in the future to augment the biosafety capacity of local agencies having limited resources. One strategy would be to develop a mobile Biosafety Level 3 autopsy laboratory. Another strategy might be to develop regional Biosafety Level 3 autopsy centers that can handle cases from surrounding jurisdictions or states. A combination of the two approaches will probably achieve the best coverage of national needs. Acknowledgments This report was prepared with the assistance and support of the members of NAME, Michael A. Graham, M.D., President. The concept for this report originated with Lynda Biedrzycki, M.D. (member of NAME), of the Waukesha County, Wisconsin, Medical Examiner's Office. The preparers of this report appreciate the early organizational efforts of John Teggatz, M.D., of the Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, Medical Examiner's Office, and the editorial comments of Victor Weedn, M.D., J.D., Carnegie Mellon University; Mary Ann Sens, M.D., Ph.D., University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences; Samuel L. Groseclose, D.V.M., CDC. The preparers also thank Aldo Fusaro, M.D., of the Cook County, Illinois, Medical Examiner's Office for compiling Appendix B. References

* Member of the National Association of Medical Examiners (NAME). † Additional information is available by contacting CDC by telephone (404-639-3133) or by fax (404-639-3043). § Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act, as amended by Public Law 106-390, October 30, 2000, United States Code, Title 42, The Public Health and Welfare, Chapter 68, Disaster Relief. ¶ State requests should be directed to the Department of Homeland Security, National Disaster Medical System Section, by telephone at 301-443-1167 (or 800-USA-NDMS) or by fax at 301-443-5146 (or 800-USA-KWIK). Table 1  Return to top. Figure 1  Return to top. Box 1  Return to top. Figure 2  Return to top. Box 2  Return to top. Figure 3  Return to top. Table 4  Return to top. Figure 4  Return to top. Figure 5  Return to top. Figure 6  Return to top. Figure 7  Return to top. Figure 8  Return to top. Figure 9  Return to top. Figure 10  Return to top. Figure 11  Return to top. Figure 12  Return to top. Figure 13  Return to top. Figure 14  Return to top. Figure 15  Return to top. Figure 16  Return to top. Figure 17  Return to top. Figure 18  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 6/9/2004 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 6/9/2004

|