Key points

- Trichinellosis, caused by the parasite Trichinella, is acquired by consuming certain meats that are undercooked or raw.

- The severity of trichinellosis is related to the infectious dose and host characteristics.

- Disease signs and symptoms typically wane after several months.

- Trichinella infections are most often diagnosed via detection of antibodies; muscle biopsy is less frequent.

Overview

Trichinellosis is caused by infection with the parasite Trichinella. The severity of disease is related to the infectious dose and host characteristics, such as age of the patient or immunological priming as a result of previous Trichinella infection. Some reports have linked severity of disease to the infecting species of Trichinella, suggesting that certain species are more likely to cause severe disease than others. However, the pathogenicity of various species is difficult to define clinically without quantifying infectious dose.

The incubation period ranges from 1 – 2 days (enteral phase) to 2 – 8 weeks (parenteral phase) or more, depending on the infectious dose. Digestion releases the parasite larvae from the meat, then larvae penetrate the intestinal mucosa where they mature into adult worms. The adult worms mate and produce new larvae, which migrate via the bloodstream to skeletal muscle throughout the body. The immune response leads to expulsion of the adult worms after several weeks, but the larvae, once in striated muscle cells, can persist for months or years.

Clinical presentation

Disease signs and symptoms typically wane after several months. Earlier signs of trichinellosis—diarrhea, fever, myalgia, and edema, especially of the face—correspond to the new larvae migration through the body and can persist days to weeks. In addition to physical damage to affected tissues, larval penetration and tissue migration cause an immune-mediated inflammatory reaction and stimulate the development of eosinophilia. More severe manifestations include myocarditis, encephalitis, and thromboembolic disease.

Risk factors

Patients become infected with Trichinella after consuming raw or undercooked implicated meat. Implicated meat is usually not sourced from commercially farmed food animals, but instead sourced from carnivorous and omnivorous wild animals. Typical sources of infection are undercooked pork or wild game meats, in particular, bear, wild boar, wildcat, fox, wolf, seal, or walrus.

Homemade jerky and sausage made from the meats listed above can also be sources for trichinellosis.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of trichinellosis is based on history of consumption of potentially contaminated meat, the presence of compatible signs and symptoms, and identification of Trichinella larvae in biopsy muscle tissue or specific antibody in serum. For outbreak-associated infections, the diagnosis can be made in asymptomatic persons on the basis of positive results on laboratory testing and history of consumption of an implicated meat. Diagnosis can be challenging, particularly in non-outbreak settings. In the early stages of disease, signs and symptoms are non-specific (see Disease) and mimic those of many other illnesses. For example, the diarrhea that can occur in the first weeks of Trichinella infection is also a common symptom of other foodborne diseases such as salmonellosis, and the fever and myalgia in the acute phase of Trichinella infection are also suggestive of influenza virus infection.

Trichinella infections are most often diagnosed in the laboratory based on detection of antibodies to excretory/secretory Trichinella antigen in EIA format. This antigen preparation will react with antibodies from other Trichinella species but may also cross react with non-specific antibodies. IgG antibodies can be detected approximately 12 – 60 days post-infection. Antibody development depends on the amount of infective Trichinella larvae that are consumed. Levels peak in the second- or third-month post-infection and then decline but may be detectable for 10 years or more following infection. At least two serum specimens should be drawn and tested weeks apart to demonstrate seroconversion in patients with suspected trichinellosis whose initial results were negative or weakly positive. Immunologic tests for Trichinella infection have the potential for cross-reactivity with sera from patients with other conditions, especially other parasitic infections.

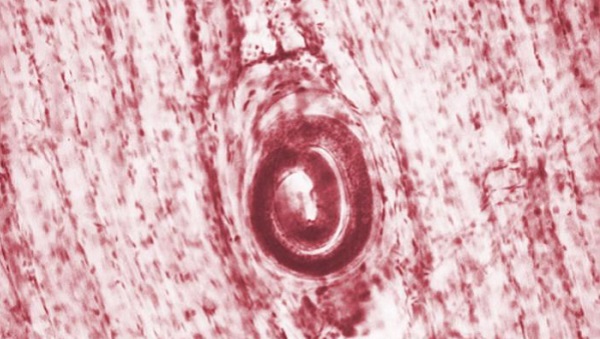

Muscle biopsies are infrequently performed, but they allow for the molecular identification of the Trichinella species or genotype, which is not possible with antibody testing. Usually, 0.2 to 0.5 grams of human or animal skeletal muscle tissue is collected and examined for Trichinella larvae via artificial digestion or histological analysis.

Surveillance & Outbreak Investigation

- Foodborne Disease Surveillance and Outbreak Investigation Toolkit

- Foodborne Outbreak Surveillance Data

- Trichinellosis Case Report Form

Serum and muscle biopsy specimens can be sent to CDC for confirmation. For questions regarding diagnosis confirmation, contact the Parasitic Diseases Hotline at parasites@cdc.gov.