At a glance

Unintentional injuries are a leading cause of death in adults ages 65 and older (older adults)—leading to nearly 70,000 deaths in 2021. Over half of these deaths are due to falls. Falls can be prevented, and you can help.

Social connectedness

Social connectedness is the degree to which people feel they belong and are supported and valued in their relationships with others. Older adults are at an increased risk for experiencing social isolation and loneliness due to changes in physical abilities, reduced mobility, chronic illness, loss of family and friends, and living alone. Nearly a quarter of older adults experience social isolation.1

Prolonged loneliness and social isolation can have significant adverse effects on physical health and emotional wellbeing and have been found to be associated with:21

- Cardiovascular disease and stroke

- Dementia

- Hypertension

- Increased hospitalization

- Premature death

- Substance use

- Suicide ideation and attempts

- Type 2 diabetes

However, social isolation and loneliness can be prevented, and you can help.

Promote social connectedness

Ask.

Ask your patients about:

- The number, quality, and types of relationships they have

- How frequently they engage with others

- How often they get the social and emotional support they need

- How often they feel lonely

- Activities they enjoy and recommend modifications based on their current physical abilities

- Barriers they may face to connecting with others and strategize solutions

Assess and intervene.

Reduced mobility caused by falls or driving cessation can have negative impacts on physical and mental health—leading to isolation and feelings of loneliness.

- Evaluate for fall risk

- Screen for factors that may affect safe driving and treat as appropriate (refer to the Clinician's Guide to Assessing and Counseling Older Drivers for information about this process)

Encourage.

- Encourage your patients to interact more frequently with others

- Suggest that they engage in activities they already enjoy and to invite others to join—such as crafts, reading (book club), and physical activities (walking or pickleball)

Social connectedness resources for health care providers

Preventing a fall

Falls are the leading cause of both fatal and nonfatal injuries in people ages 65 and older and falls can lead to significant functional decline and extensive medical costs. More than 1 in 4 older adults fall each year and falling once increases their chances of falling again.34 Falls can be prevented, and you can help.

What can you do to prevent your older patients from falling?

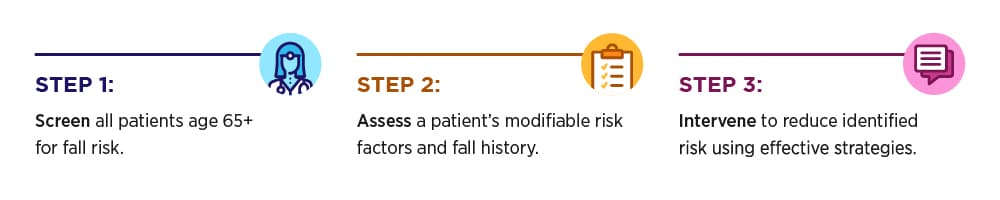

Screen.

Screen patients for fall risk.

Assess.

Assess modifiable fall risk factors.

Intervene.

Intervene to reduce identified fall risk by using effective clinical and community strategies.

Fall prevention resources for health care providers

- STEADI (Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, and Injuries) Initiative

- Fall Risk Screening Tool: Falls Free CheckUp

Motor vehicle safety

As Americans live longer, there are more older adults ages 65 and older driving longer. There were nearly 50 million licensed older adult drivers in 2022.5

Driving helps keep older adults mobile and independent but their risk of injury or death in a motor vehicle crash increases as they get older. Over 9,100 older adults died in traffic crashes in 2022 and more than 200,000 were treated in emergency departments for crash injuries in 2021.6 This means that 25 older adults die and more than 550 sustain an injury every day in motor vehicle crashes.

What can you do to prevent motor vehicle crash deaths and injuries in your patients?

Screen and assess potential driving concerns.

- Provide an in-office assessment to identify medical conditions, functional skills, or history of recent crashes that could affect a patient's ability to drive safely.

Review medications.

- Review your patient's prescription and over-the-counter medicines for adverse effects that could increase the risk of a car crash.

- Assess whether your patient can move to a lower dosage of medicines or discontinue use.

Evaluate and treat.

- You may be able to treat the relevant medical conditions or functional limitations to address the underlying conditions.

Refer patients for driving assessments as indicated.

- Patients whose limitations are not addressed by optimal medical treatment can be referred to a driving rehabilitation specialist for additional evaluation, rehabilitation, or training.

Educate.

- Talk to your patients about their modifiable risk factors, such as staying active and wearing proper eyewear.

- Older adults should have their eyes checked by an eye doctor at least once a year and update their eyeglasses as needed.

Encourage transportation options.

- The chances of motor vehicle crashes resulting in injuries or death increase as we age.

- Encourage your patients to consider ride shares, public transportation, or asking friends, family members, or neighbors to drive them.

Motor vehicle safety resources for health care providers

Traumatic brain injury

A traumatic brain injury (TBI) may lead to devastating health effects and is linked to a substantial number of deaths and disabilities in the United States each year. A TBI can occur in several ways but falls and motor vehicle crashes are two of the most common causes, especially in adults ages 65 and older. In fact, 81% of TBI-related emergency department visits in older adults are caused by falls.7

Older adults are more likely to have a hospital stay and die from a TBI compared to other age groups.8 Still, TBIs may be missed or misdiagnosed because symptoms of TBI overlap with other medical conditions that are common among older adults, such as dementia.

Check your older patients for signs and symptoms of a TBI if they have fallen or were in a car crash. This is especially important among older adults who are taking blood thinners,9 such as:

- Anticoagulants such as warfarin (Coumadin), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and apixaban (Eliquis)

- Antiplatelet medications such as clopidogrel (Plavix), ticagrelor (Brilinta), and acetylsalicylic acid (Aspirin)

When to initiate immediate medical intervention

Signs of deteriorating neurological function may include:

- Headache that gets worse and does not go away

- Experience weakness, numbness, decreased coordination, convulsions, or seizures

- Vomit repeatedly

- Slurred speech or unusual behavior

- One pupil larger than the other

- Cannot recognize people or places, get confused, restless, or agitated

- Lose consciousness, look very drowsy, or cannot wake up

What can you do to prevent a TBI in your patients?

Practice fall prevention.

Advise older patients to follow the steps in how you can prevent a fall.

Increase motor vehicle safety.

Advise your older patients to follow the steps in preventing a motor vehicle crash.

Traumatic brain injury resources for health care providers

- Traumatic Brain Injury & Concussion Resources for Healthcare Providers

- Guideline for Adult Patients with Mild TBI

- What do Expect After a Concussion: Patient Discharge Discussion Sheet (English | Spanish) [4 pages]

- Key Recommendations for the Care of Adult Patients with Mild Traumatic Brain Injury [1 page]

- Checklist to Assess for and Manage Mild Traumatic Brain Injury & Concussion [1 page]

- Holt-Lunstad J. Social Connection as a Public Health Issue: The Evidence and a Systemic Framework for Prioritizing the "Social" in Social Determinants of Health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2022;43:193-213.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System. National Academies Press (US); 2020. DOI: 10.17224/25663.

- Moreland B, Kakara R, Henry A. Trends in Nonfatal Falls and Fall-related Injuries Among Adults Aged ≥65 Years—United States, 2012–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:875–881.

- Pohl P, Nordin E, Lundquist A, Bergström U, Lundin-Olsson L. Community-dwelling Older People with an Injurious Fall Are Likely to Sustain New Injurious Falls Within 5 Years—A Prospective Long-term Follow-up Study. BMC Geriatrics. 2014 Nov 18;14:120.

- U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. Highway Statistics 2022 - Policy | Federal Highway Administration. Accessed 2023.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). Atlanta, GA: CDC; Accessed 2023.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Surveillance Report of Traumatic Brain Injury-related Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths—United States, 2014. (Assessed 2019).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022). Surveillance Report of Traumatic Brain Injury-related Deaths by Age Group, Sex, and Mechanism of Injury—United States, 2018 and 2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Maegele M, Schöchl H, Menovsky T, Maréchal H, Marklund N, Buki A, Stanworth S. Coagulopathy and Haemorrhagic Progression in Traumatic Brain Injury: Advances in Mechanisms, Diagnosis, and Management. Lancet Neurol. 2017 Aug; 16(8):630–647.