Purpose

This page contains information for clinicians about Acute Radiation Syndrome (ARS). It includes information about causes, stages, patient management and information on Cutaneous Radiation Injury (CRI).

Overview

This page is not for the public.

Acute Radiation Syndrome (ARS) (sometimes known as acute radiation sickness) is an acute illness caused by radiation exposure (or irradiation) of the entire body (or most of the body) by a high dose of penetrating radiation in a very short period of time (usually a matter of minutes).

The major cause of this syndrome is depletion of immature parenchymal stem cells in specific tissues. Examples of people who suffered from ARS are the survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombs and the firefighters that first responded after the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant event in 1986. Unintentional exposures to sterilization irradiators have also caused ARS.

Conditions for ARS

The required conditions for Acute Radiation Syndrome (ARS) are

- The radiation dose must be large (i.e., greater than 0.7 Gray (Gy)A or 70 radsB). Mild symptoms may be observed with doses as low as 0.3 Gy or 30 rads.

- The dose usually must be external ( i.e., the source of radiation is outside of the patient's body). Radioactive materials deposited inside the body have produced some ARS effects only in extremely rare cases.

- The radiation must be penetrating (i.e., able to reach the internal organs).High energy X-rays, gamma rays, and neutrons are types of penetrating radiation.

- The entire body (or a significant portion of it) must have received the doseC. Most radiation injuries are partial body, frequently involving only the hands, and these local injuries seldom cause classical signs of ARS.

- The dose must have been delivered in a short time (usually a matter of minutes). Fractionated doses are often used in radiation therapy. These are large total doses delivered in small daily amounts over a period of time. Fractionated doses are less effective at inducing ARS than a single dose of the same magnitude.

The three classic acute radiation syndromes

Bone marrow syndrome (sometimes referred to as hematopoietic syndrome): the full syndrome will usually occur with a dose between 0.7 and 10 Gy (70 – 1000 rads). Mild symptoms may occur as low as 0.3 Gy or 30 radsD.

The survival rate of patients with this syndrome decreases with increasing dose. The primary cause of death is the destruction of the bone marrow, resulting in infection and hemorrhage.

Gastrointestinal (GI) syndrome: the full syndrome will usually occur with a dose greater than approximately 10 Gy (1000 rads). Some symptoms may occur as low as 6 Gy or 600 rads.

Survival is extremely unlikely with this syndrome. Destructive and irreparable changes in the GI tract and bone marrow usually cause infection, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalance. Death usually occurs within 2 weeks.

Cardiovascular (CV)/ Central Nervous System (CNS) syndrome: the full syndrome will usually occur with a dose greater than approximately 50 Gy (5000 rads). Some symptoms may occur as low as 20 Gy or 2000 rads.

Death may occur within 3 days. Death likely is due to collapse of the circulatory system as well as increased pressure in the confining cranial vault as the result of increased fluid content caused by edema, vasculitis, and meningitis.

The four stages of ARS

- Prodromal stage (N-V-D stage): The classic symptoms for this stage are nausea, vomiting, as well as anorexia and possibly diarrhea (depending on dose), which occur from minutes to days following exposure. The symptoms may last (episodically) for minutes up to several days.

- Latent stage: In this stage, the patient looks and feels generally healthy for a few hours or even up to a few weeks.

- Manifest illness stage: In this stage the symptoms depend on the specific syndrome (see Table 1) and last from hours up to several months.

- Recovery or death: Most patients who do not recover will die within months of exposure. The recovery process lasts from several weeks up to two years.

These stages are described in further detail in Table 1.

Table 1: Acute Radiation Syndromes

| Syndrome | Dose* | Prodromal Stage | Latent Stage | Manifest Illness Stage | Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematopoietic (Bone Marrow) |

> 0.7 Gy (> 70 rads) (mild symptoms may occur as low as 0.3 Gy or 30 rads) |

• Symptoms are anorexia, nausea and vomiting. • Onset occurs 1 hour to 2 days after exposure. • Stage lasts for minutes to days. |

• Stem cells in bone marrow are dying, although patient may appear and feel well. • Stage lasts 1 to 6 weeks. |

• Symptoms are anorexia, fever, and malaise. • Drop in all blood cell counts occurs for several weeks. • Primary cause of death is infection and hemorrhage. • Survival decreases with increasing dose. • Most deaths occur within a few months after exposure. |

• In most cases, bone marrow cells will begin to repopulate the marrow. • There should be full recovery for a large percentage of individuals from a few weeks up to two years after exposure. • Death may occur in some individuals at 1.2 Gy (120 rads). • The LD50/60† is about 2.5 to 5 Gy (250 to 500 rads). |

| Gastrointestinal (GI) | > 10 Gy (> 1000 rads) (some symptoms may occur as low as 6 Gy or 600 rads) |

• Symptoms are anorexia, severe nausea, vomiting, cramps, and diarrhea. • Onset occurs within a few hours after exposure. • Stage lasts about 2 days. |

• Stem cells in bone marrow and cells lining GI tract are dying, although patient may appear and feel well. • Stage lasts less than 1 week. |

• Symptoms are malaise, anorexia, severe diarrhea, fever, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalance. • Death is due to infection, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalance. • Death occurs within 2 weeks of exposure. |

• The LD100‡ is about 10 Gy (1000 rads). |

| Cardiovascular (CV)/ Central Nervous System (CNS) | > 50 Gy (5000 rads) (some symptoms may occur as low as 20 Gy or 2000 rads) |

• Symptoms are extreme nervousness and confusion; severe nausea, vomiting, and watery diarrhea; loss of consciousness; and burning sensations of the skin. • Onset occurs within minutes of exposure. • Stage lasts for minutes to hours. |

• Patient may return to partial functionality. • Stage may last for hours but often is less. |

• Symptoms are return of watery diarrhea, convulsions, and coma. • Onset occurs 5 to 6 hours after exposure. • Death occurs within 3 days of exposure. |

• No recovery is expected. |

Cutaneous Radiation Injury

The concept of Cutaneous Radiation Injury (CRI) describes the complex pathological syndrome that results from acute radiation exposure to the skin.

ARS usually will be accompanied by some skin damage. It is also possible to receive a damaging dose to the skin without symptoms of ARS, especially with acute exposures to beta radiation or X-rays. Sometimes this occurs when radioactive materials contaminate a patient's skin or clothes.

When the basal cell layer of the skin is damaged by radiation, inflammation, erythema, and dry or moist desquamation can occur. Also, hair follicles may be damaged, causing epilation. Within a few hours after irradiation, a transient and inconsistent erythema (associated with itching) can occur. Then, a latent phase may occur and last from a few days up to several weeks, when intense reddening, blistering, and ulceration of the irradiated site are visible.

In most cases, healing occurs by regenerative means. However, very large skin doses can cause permanent hair loss, damaged sebaceous and sweat glands, atrophy, fibrosis, decreased or increased skin pigmentation, and ulceration or necrosis of the exposed tissue.

Patient management

Triage

If radiation exposure is suspected

- Secure ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation) and physiologic monitoring (blood pressure, blood gases, electrolyte and urine output) as appropriate.

- Treat major traumatic burns and respiratory injuries if evident.

- In addition to the blood samples required to address the trauma, obtain blood samples for CBC (complete blood count), with attention to lymphocyte count, and HLA (human leukocyte antigen) typing prior to any initial transfusion and at periodic intervals following transfusion.

- Provide decontamination for external contamination, if necessary.

- If exposure occurred within 8 to 12 hours, repeat CBC, with attention to lymphocyte count, 2 or 3 more times (approximately every 2 to 3 hours) to assess lymphocyte depletion.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of ARS can be difficult to make because ARS causes no unique sign or symptom. Also, depending on the dose, the prodromal stage may not occur for hours or days after exposure, or the patient may already be in the latent stage by the time they receive treatment, in which case the patient may appear and feel well when first assessed.

If a patient received more than 0.05 Gy (5 rads) and three or four CBCs are taken within 8 to 12 hours of the exposure, a quick estimate of the dose can be made (see Ricks, et. al. for details). If these initial blood counts are not taken, the dose can still be estimated by using CBC results over the first few days. It would be best to have radiation dosimetrists conduct the dose assessment, if possible.

If a patient is known to have been or suspected of having been exposed to a large radiation dose, draw blood for CBC analysis with special attention to the lymphocyte count, every 2 to 3 hours during the first 8 hours after exposure (and every 4 to 6 hours for the next 2 days). Observe the patient during this time for symptoms and consult with radiation experts before ruling out ARS.

If no radiation exposure is initially suspected, you may consider ARS in the differential diagnosis if a history exists of nausea and vomiting that is unexplained by other causes. Other indications are bleeding, epilation, or white blood count (WBC) and platelet counts abnormally low a few days or weeks after unexplained nausea and vomiting. Again, consider CBC and chromosome analysis and consultation with radiation experts to confirm diagnosis.

Initial treatment and diagnosis evaluation

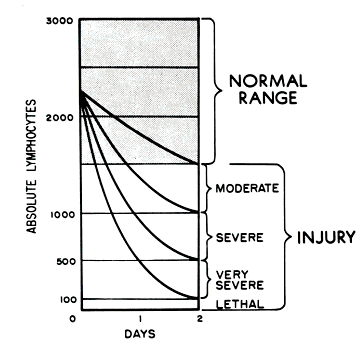

Treat vomitingE, and repeat CBC analysis, with special attention to the lymphocyte count, every 2 to 3 hours for the first 8 to 12 hours following exposure (and every 4 to 6 hours for the following 2 or 3 days). Sequential changes in absolute lymphocyte counts over time are demonstrated below in the Andrews Lymphocyte Nomogram (see Figure 1). Precisely record all clinical symptoms, particularly nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and itching, reddening or blistering of the skin. Be sure to include time of onset.

Figure 1: Andrews Lymphocyte Nomogram

Note and record areas of erythema. If possible, take color photographs of suspected radiation skin damage. Consider tissue, blood typing, and initiating viral prophylaxis. Promptly consult with radiation, hematology, and radiotherapy experts about dosimetry, prognosis, and treatment options. Call the Radiation Emergency Assistance Center/Training Site (REAC/TS) at (865) 576-3131 (M-F, 8 am to 4:30 am EST) or (865) 576-1005 (after hours) to record the incident in the Radiation Accident Registry System.

After consultation, begin the following (as indicated):

- Supportive care in an environment that provides neutropenic precautions (if available, the use of a burn unit may be quite effective)

- Prevention and treatment of infections

- Stimulation of hematopoiesis by use of growth factors

- Stem cell transplantation or platelet transfusions (if platelet count is too low)

- Psychological support

- Careful observation for erythema (document locations), hair loss, skin injury, mucositis, parotitis, weight loss, or fever

- Confirmation of initial dose estimate using chromosome aberration cytogenetic bioassay when possible (although resource intensive, this is the best method of dose assessment following acute exposures)

- Consultation with experts in radiation accident management

Resources

Radiological Terrorism: Emergency Management Pocket Guide for Clinicians

A Brochure for Physicians: Acute Radiation Syndrome

Table 1 footnotes

*The absorbed doses quoted here are “gamma equivalent” values. Neutrons or protons generally produce the same effects as gamma, beta, or X-rays but at lower doses. If the patient has been exposed to neutrons or protons, consult radiation experts on how to interpret the dose.

†The LD50/60 is the dose necessary to kill 50% of the exposed population in 60 days.

‡The LD100 is the dose necessary to kill 100% of the exposed population.

- The Gray (Gy) is a unit of absorbed dose and reflects an amount of energy deposited into a mass of tissue (1 Gy = 100 rads). In this document, the referenced absorbed dose is that dose inside the patient’s body (i.e., the dose that is normally measured with personal dosimeters).

- The referenced absorbed dose levels in this document are assumed to be from beta, gamma, or x radiation. Neutron or proton radiation produces many of the health effects described herein at lower absorbed dose levels.

- The dose may not be uniform, but a large portion of the body must have received more than 0.7 Gy (70 rads).

- Note: although the dose ranges provided in this document apply to most healthy adult members of the public, a great deal of variability of radiosensitivity among individuals exists, depending upon the age and condition of health of the individual at the time of exposure. Children and infants are especially sensitive.

- Collect vomitus in the first few days for later analysis.

- Berger ME, O'Hare FM Jr, Ricks RC, editors. The Medical Basis for Radiation Accident Preparedness: The Clinical Care of Victims. REAC/TS Conference on the Medical Basis for Radiation Accident Preparedness. New York : Parthenon Publishing; 2002.

- Gusev IA , Guskova AK , Mettler FA Jr, editors. Medical Management of Radiation Accidents, 2 nd ed., New York : CRC Press, Inc.; 2001.

- Jarrett DG. Medical Management of Radiological Casualties Handbook, 1 st ed. Bethesda , Maryland : Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute (AFRRI); 1999.

- LaTorre TE. Primer of Medical Radiobiology, 2 nd ed. Chicago : Year Book Medical Publishers, Inc.; 1989.

- National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements (NCRP). Management of Terrorist Events Involving Radioactive Material, NCRP Report No. 138. Bethesda , Maryland : NCRP; 2001.

- Prasad KN. Handbook of Radiobiology, 2 nd ed. New York : CRC Press, Inc.; 1995.