At a glance

Learn how newborn screening can save babies' lives. It can help them get the treatment they may need as early as possible.

Introduction

Milan & Elena Villarreal know the heartbreak of losing a child to a genetic disease. When their first daughter, Josephine, was 6 months old, she was diagnosed with spinal muscular atrophy, or SMA type 1. The disorder causes progressive, severe muscle weakness and tone that leads to significant developmental delay. Left untreated, children often die before age 2. Josephine passed away 9 months later.

The Villarreals also know the joy of seeing a child flourish. When their second daughter, Evelyn, was born in 2014, they realized she too might have SMA because they are carriers of the defective SMN1 gene. When Evelyn was just a few weeks old, a blood test confirmed their worst fears. They already had seen how SMA limits an infant's ability to sit, walk, swallow, and breathe.

"We knew what we were dealing with," says Milan Villarreal. "The only reason we knew to test Evelyn is because she had a sister who died from SMA. No one should have to go through that. Newborn screening not only can save their lives but also their mobility."

Milan urgently searched online for research and treatment options for Evelyn and learned about a clinical trial in Ohio that would provide gene therapy treatment to replace a critical protein for maintaining normal muscle function.

Photo courtesy of Villarreal family

"Evelyn was born in the right time and place. We were able to get this treatment early," says her mom, Elena. The Villarreals have celebrated every milestone Evelyn has achieved. She was the first baby in the clinical trial who was able to roll over—a big breakthrough. "We didn't tell the doctors before our check-up because we wanted to surprise them. Our neurologist just cried," recalls Elena. "As Evelyn progressed, she was the first one to walk. It was all very exciting. It just brought so much hope."

Photo courtesy of Villarreal family

Now Evelyn, 9, goes to school, enjoys science and art, draws pictures, writes stories, speed-walks, swims, and flies kites. Mostly, though, she loves to play with her 4-year-old baby sister, Mila, who doesn't have SMA, but is a carrier for the defective SMN1 gene.

The Villarreals say they are passionate about newborn screening, because it can help children get treatment as early as possible, which is critical for SMA.

Early diagnosis is key

SMA type I is now one of the conditions that is recommended for inclusion in routine public health newborn screening in the U.S. One in 10,000 babies are born with SMA. Early diagnosis is crucial for survival as well as improving their quality of life. Accurate testing means that care and treatment can start right away, allowing newborns to avoid lifelong health problems or an early death.

The Division of Laboratory Sciences in CDC's National Center for Environmental Health plays an important role in newborn screening through its Newborn Screening Quality Assurance Program. The program supports states with training, consultation, proficiency testing, quality assurance materials, and one-to-one technical assistance for their laboratories.

CDC has the world's only laboratory to enhance and maintain the quality and accuracy of newborn screening test results for certain genetic, metabolic, and endocrine disorders in 50 states and across the globe. Every state screens newborns for many serious but treatable congenital diseases. These range from SMA, cystic fibrosis, and sickle cell disease to endocrine diseases, multiple inborn errors of metabolism, and lysosomal storage diseases. Early and accurate testing allows babies to be diagnosed and treated right away.

How it works

Health professionals take a few drops of blood from newborn babies' heels, blot samples onto special filter paper, then send them to state laboratories to screen for severe disorders. CDC's Newborn Screening and Molecular Biology Branch in the Division of Laboratory Sciences supports the effort.

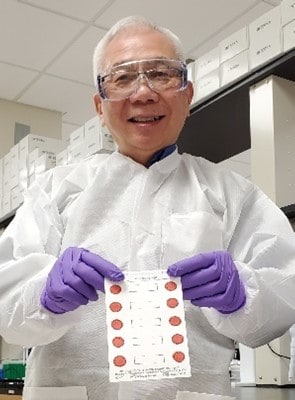

Photo courtesy of Suzanne Cordovado

CDC creates dried blood spots to simulate the sample types that newborn screening laboratories test. Laboratories use these sample spots to make sure their tests are accurate.

"We make about a million dried blood spots every year," explains Joanne Mei, who leads CDC's Newborn Screening Quality Assurance Program. "This work starts in the early morning, with people preparing the filter paper cards. We lay the cards out on a rack, and a robot spots the blood onto them. We add different biochemical markers or include cells from patient samples with specific molecular markers, depending on what newborn screening disorder we're trying to mimic."

Newborn screening laboratories around the world depend on these materials, known as dried blood spot quality assurance samples, to provide an external check on their work. The samples help them identify the biochemical or molecular markers associated with newborn screening disorders.

The materials to make quality-assurance dried blood spots for a disorder that uses molecular tests cannot be bought off the shelf. These tests look for DNA, and the source comes from the blood of donor patients who have the disorder.

A creative solution

The Molecular Quality Improvement Program (MQIP), also part of CDC's Newborn Screening and Molecular Biology Branch, addressed the challenge by working with the Sequoia Foundation in partnership with the California Department of Public Health to obtain blood samples from patients and family members with rare disorders like SMA.

MQIP created a process to grow large quantities of cells that were originally derived from patient blood. Researchers infect these patient cells with the Epstein-Barr Virus, which allows the cells to grow indefinitely. Now CDC has a reliable source to make large quantities of dried blood spots with the specific DNA variants that cause disease.

In 2020 and 2021, CDC successfully piloted this new sample type for use in newborn screening laboratories to detect SMA, severe combined immunodeficiency, and cystic fibrosis. CDC now has rolled out this type of dried blood spot materials to all states and several global programs screening for proficiency testing of SMA and severe combined immunodeficiency.

Laboratories can also use the samples to develop or validate new screening tests. This allows even more babies to benefit. It's all about the babies—and the labs that support them by saving and promoting healthier lives.