What to know

- As fall and winter virus season begins, CDC is providing the latest data on respiratory disease activity to help you make informed decisions.

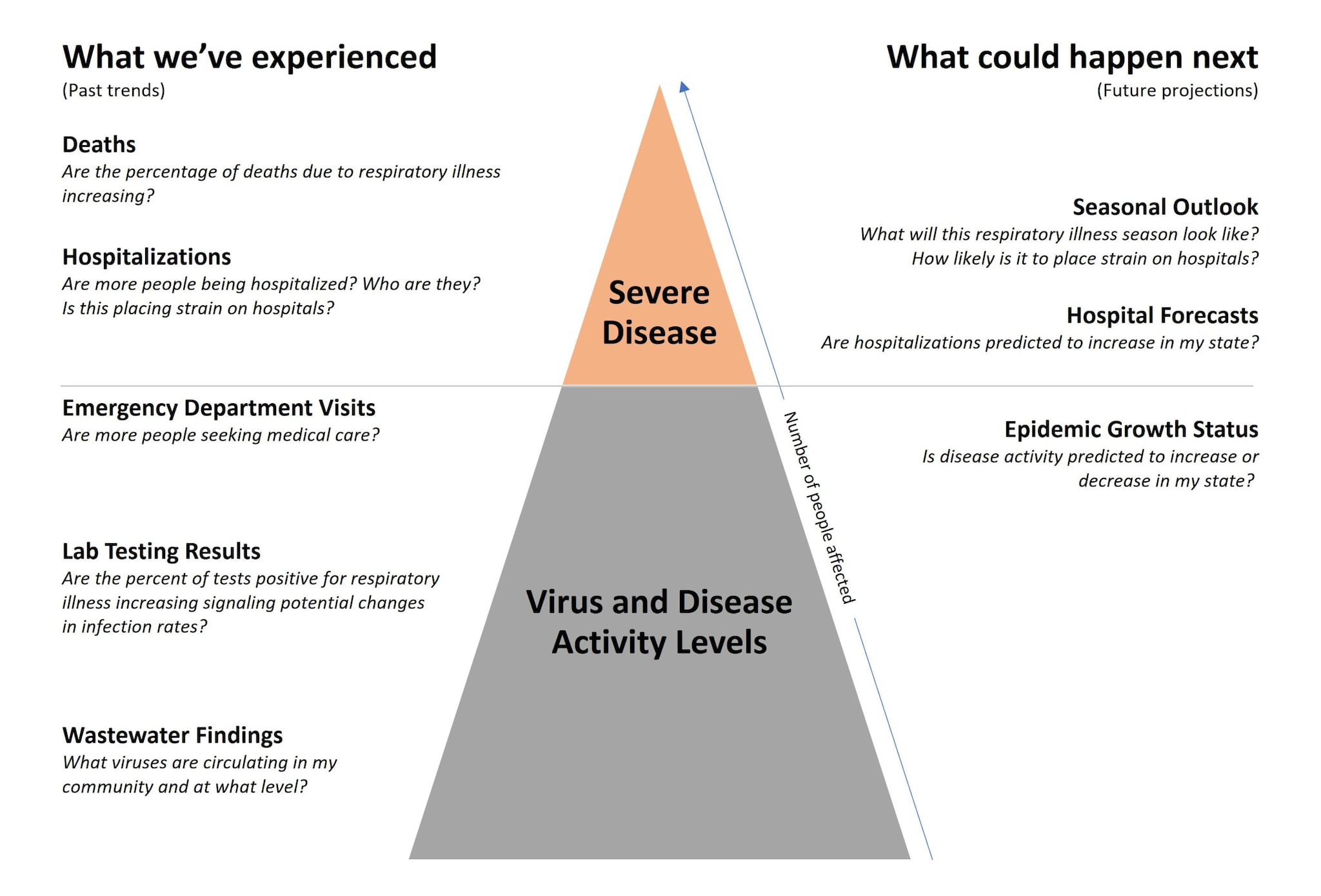

- CDC uses multiple data systems and tools to detect and track disease activity, monitor disease severity, and forecast respiratory illness threats.

Summary

What CDC knows

It's fall and winter virus season, so it's time to get your recommended immunizations, one of the core strategies in CDC's respiratory virus guidance. Layering on other strategies, like meeting outdoors or wearing a mask, may depend on virus activity in your area. To help you make informed decisions, CDC shares timely data on respiratory illnesses.

What CDC is doing

CDC collects a variety of respiratory illness data and has taken steps to clearly show trends in disease activity and illness severity. Check out CDC's updated Respiratory Illness Data Channel for the latest information on trends in flu, COVID-19, and RSV, as well as overall respiratory illnesses.

Understanding the challenges of tracking respiratory illnesses

October is here, which means we're now in the fall and winter virus season. While respiratory illnesses are present throughout the year, the fall and winter months are a time when we need to be extra aware of what viruses are spreading and who is impacted the most. CDC uses data from different sources to answer important questions regarding respiratory illness activity and severity. This can help you make informed decisions to protect yourself, your loved ones, and your community. You can find a summary of this information on the Respiratory Illness Data Channel every week.

Respiratory illnesses include many conditions, including viral diseases such as flu, COVID-19, and RSV, as well as bacterial and fungal diseases, like some types of pneumonia. A common question CDC gets is: "If you aren't counting every case of a respiratory disease, like COVID-19, how do you know how bad things are?" Collecting information about cases is an important tool that public health uses to identify and monitor certain diseases, including those designated as being nationally notifiable. However, it isn't always the most useful or efficient approach to help guide public health action. This is especially true when the disease is common and not always diagnosed or reported.

Fortunately, public health agencies have many ways to gauge the threat respiratory diseases pose to communities across the nation. CDC uses multiple data systems and tools to detect and track respiratory illness activity, monitor disease severity, and forecast expected trends. These systems are used for overall, ongoing respiratory illness situational awareness and can be adapted for specific disease types or emergency public health responses if needed. Sometimes disease trends in these systems differ or appear to differ. When trying to interpret these differences, it is helpful to know how the systems work, what they monitor, and what important public health questions they can answer.

Surveillance can tell us about respiratory virus and disease activity

CDC currently uses three main types of data systems to track respiratory virus and disease activity.

Lab test positivity

CDC has multiple systems, such as the National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System, that collect laboratory testing results from clinical, public health, and commercial laboratories. Each system represents different subsets of the population. Monitoring the total number of positive tests is not as useful because how people are tested can change. Instead, we monitor the percentage of tests that are positive instead of focusing on total numbers. This measure provides an early indicator of increases in infections, as well as an effective signal for when we've passed a seasonal peak. It is important to note that some laboratory monitoring systems focus primarily on identifying new or different subtypes or variants of viruses that cause flu and COVID-19 rather than focusing on test positivity.

Emergency department visits

CDC relies on data from a robust network of emergency departments covering about 81% of emergency departments in the United States. This system helps us monitor changes in demand for medical services based on information collected during emergency department visits. These data provide public health agencies insight into the burden of diseases, including respiratory illnesses. CDC analyzes de-identified information, which is stripped of any personal details, on both patients' "chief complaints" (in response to questions like, "Why did you come in today?") and their specific diagnoses. This dual approach helps us track conditions with a diagnosis, like COVID-19, and those that might not have a pathogen-specific diagnosis, such as shortness of breath. Emergency department visits with a diagnosis currently underlie CDC's Respiratory Illnesses Data Channel, including the newly added acute respiratory illness metric, or ARI.

As of October 4, 2024, the ARI metric is available as a snapshot of the amount of overall respiratory illness requiring care at an emergency department at the state and national levels. Instead of focusing on specific diseases, like COVID-19, the ARI metric is based on a wide range of respiratory illness diagnoses and chief complaints from emergency department visits. At times, increases in this metric may be driven primarily by specific diseases like flu or COVID-19. Sometimes these increases can be due to a wide range of illnesses such as:

- Chronic conditions (like asthma)

- Acute conditions (like a heart attack)

- Other viruses

- Bacteria

- Or fungi

Wastewater data

Wastewater surveillance tests for genetic traces of viruses, including those that cause flu, COVID-19, and RSV, in sewer systems. These sewer systems currently cover about 40% of the U.S. population. Wastewater data can provide early indication of disease spread and provide information on overall virus levels, not just infection in people who seek medical care. These data can be a bit "noisier" (prone to irregularities that can make trends less clear) than emergency department data. This is especially so at the state or local levels, so use caution when interpreting week-to-week changes. Also, wastewater data are unable to determine the source of detected viruses, such as whether they come from humans, animals, or animal products. This can be important to understand when monitoring and responding to some viruses, such as bird flu. Wastewater testing is one of CDC's newest tools and we're still learning how to use it best in each situation.

Surveillance helps us assess disease severity and system capacity

Knowing how many people have respiratory illnesses and the viruses causing those illnesses is just a part of the picture. We also need to know how severe these illnesses are. To track disease severity, CDC uses multiple types of hospital-based systems and our National Vital Statistics System.

Hospitalizations

From 2020 through earlier this year, the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) tracked nearly every U.S. hospitalization in a person with a laboratory test positive for flu or COVID-19. This provided a comprehensive picture of cases severe enough to require hospitalization. These data played a critical role in guiding facility, health system, and community-level actions to protect patients and public health. Although reporting became voluntary in April 2024, new rules will require hospitals to start reporting again in November 2024. These rules also expand reporting to include RSV. In addition to tracking hospitalizations, hospitals will also report data on overall hospital capacity, such as the number of beds currently being used by patients. This helps identify signals of healthcare strain and identify resource needs during peak respiratory season and emerging public health events.

The Respiratory Virus Hospitalization Surveillance Network (RESP-NET) collects data on laboratory-confirmed hospitalizations with flu, COVID-19, or RSV at all acute-care hospitals within designated sites across the country. About 8–10% of the U.S. population is covered through this surveillance network. RESP-NET collects detailed information about hospitalizations occurring in a smaller geographic area to monitor trends by important demographic characteristics and answer in-depth public health questions, such as identifying important risk factors for severe health outcomes.

CDC also has access to a collection of near real-time healthcare data sources. These data sources allow us to understand clinical risk factors leading to a hospitalization, describe the care received and associated outcomes during a hospitalization, and monitor long-term clinical needs and outcomes after discharge.

Deaths

CDC's National Vital Statistics System captures information from death certificates. CDC releases provisional death data every week, helping monitor trends in respiratory illness-associated deaths. Provisional data is early information that is available right now but might change as more reports come in. These data help CDC track the percent of total deaths attributed to respiratory illnesses so we can spot concerning trends.

Forecasting the future of respiratory illness activity

While looking at current and past data is critical, CDC also uses tools to understand what is likely to happen in the future. This includes:

Epidemic trend estimates

This tool examines data on emergency department visits to estimate whether infections are currently increasing or decreasing in the state. Changes in infection trends precede similar trends in more severe outcomes, such as hospitalizations and deaths, and therefore give an indication of where the epidemic is headed.

Hospitalization forecasts

These are not yet available for this season but will soon be introduced to project expected hospitalizations up to four weeks ahead for flu and COVID-19. They rely on the data reported into NHSN.

Seasonal outlook

This outlook provides a broad assessment for the upcoming season to assist in public health preparedness. For this season, the experts predict that the combined peak hospitalizations for number of flu, COVID-19, and RSV hospitalizations will be similar to, or slightly lower than last season.

Systems and tools used to monitor respiratory illnesses

Putting the pieces together to turn data into action

CDC has a long history of monitoring respiratory illness, and these capabilities have continued to grow since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Much of this new growth, including the expansion of emergency department and wastewater monitoring, is thanks to efforts like CDC's Data Modernization Initiative and ongoing focus on the Public Health Data Strategy milestones.

Each of our data systems helps tell a different part of the story about circulating viruses and who is getting sick. Many different teams of CDC experts interpret the data from across these systems. They work together to integrate the information into meaningful key findings that are shared with the public in places like FluView and the Respiratory Illnesses Data Channel. The Respiratory Illness Data Channel:

- Summarizes findings across respiratory illness types into a weekly snapshot to highlight the most important information;

- Provides current and the most local-level data available for each condition;

- Explains what the data mean and why they are important; and

- Includes thresholds to indicate respiratory virus and disease activity levels to help with interpreting the findings.

CDC experts engage with colleagues across state and local health departments. This cooperation ensures that local context is considered when interpreting and responding to data trends.

CDC continues to work to improve how we and our partners collect, use, and share respiratory illness information. Our goal is to help individuals, hospitals, healthcare systems, and communities make informed decisions to protect health and improve lives.