At a glance

Cluster detection and response (CDR) identifies communities affected by rapid HIV transmission. Health departments and their partners then aim to address gaps in prevention and care at individual, network, and systems levels. This guidance describes actions that all health departments can take to develop capacity, engage key partners, and successfully implement CDR activities.

Overview

Cluster detection and response (CDR) identifies communities affected by rapid HIV transmission. Health departments and their partners then aim to address gaps in prevention and care at individual, network, and systems levels. This guidance describes actions that all health departments can take to develop capacity, engage key partners, and successfully implement CDR activities.

Many people contributed to the development of this guidance, including:

- Staff from CDC, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and National Institutes of Health (NIH)

- Staff from state and local health departments

- Members of the HIV CDR community implementation partners panel

CDC continues to work with partners to identify best CDR practices and will update the guidance regularly.

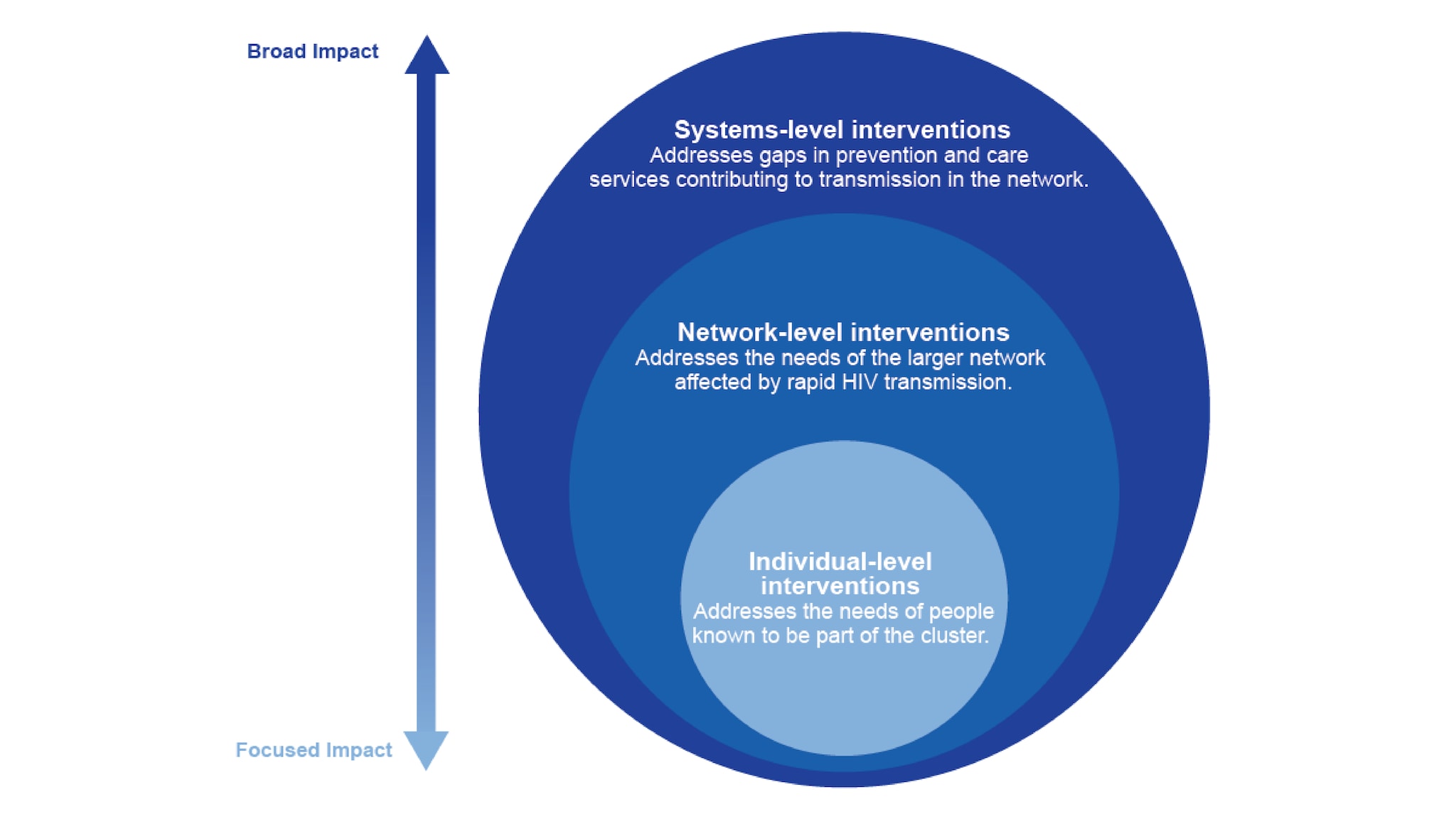

We have many tools to diagnose, treat, and prevent HIV, but sometimes these services don't reach people who need them most. HIV CDR allows public health professionals to identify and respond to rapid HIV transmission. Responding includes identifying and closing gaps in prevention and care services for affected communities. Because rapid transmission can affect people beyond the identified cluster, responding at the individual, network, and systems levels is important.

Clusters are a sign of rapid transmission

An HIV cluster or outbreak refers to rapid HIV transmission among people in a sexual or drug-using network. This can occur because communities have limited or no access to HIV prevention and care services. Stigma, discrimination, racism, poverty, and other social and structural factors all contribute to limiting access to these services. Health departments, community-based organizations (CBOs), and other partners use CDR to address these service gaps and improve health equity.

Prioritizing response to HIV clusters is important because clusters have very rapid transmission. For example:

- Transmission rates in molecular clusters average 8-11 times the national rate.

- Some clusters and outbreaks have had transmission rates more than 30 times the national rate.

- Rapidly growing clusters contribute disproportionately to future transmission.

People in detected clusters are only part of the network affected by rapid transmission

For CDR activities, "network" refers to the people in an HIV cluster and those with whom they have sex or share drugs, who may or may not have HIV. Some people with HIV can be in the network, even if they weren't part of the initially detected cluster. People without HIV in the same sexual or drug-using networks are also considered part of the larger network.

Responding to clusters at individual, network, and systems levels

Because the network experiencing rapid transmission extends beyond the detected cluster, health departments should work to understand the network. Health departments can then address gaps in prevention and care at the individual, network, and systems levels. See Cluster Investigation and Response for examples of these activities.

Guidance

CDR planning and oversight activities should include experts in diverse topics. Involving leaders who can address gaps in HIV-related prevention and care is essential for successful CDR.

CDR activities

All health departments should:

- Bring together a CDR leadership and coordination group with staff from relevant programs.

- Create a CDR plan and update it at least annually.

- Partner with community members and organizations for CDR planning and implementation.

- Analyze data to identify and prioritize clusters of rapid HIV transmission for investigation and response.

- Develop and implement actions to investigate and respond at individual, network, and systems levels.

- Communicate about CDR to a variety of audiences.

- Ensure data protections for CDR activities.

- Report cluster information to CDC.

- Participate in CDC-organized meetings.

Health departments can also enhance their CDR activities. For example:

- Hire dedicated staff for response activities.

- Routinize and automate analysis and data integration from multiple sources, including HIV and related disease areas.

- Engage with communities through a subcommittee or dedicated session of an existing planning group to collaborate on CDR activities.

- Conduct planning exercises to refine CDR plans and improve processes.

- Create a dedicated CDR fund to address needs identified through response efforts.

Staffing to support CDR

Many staffing arrangements can successfully support CDR activities. Staff may work on CDR full-time, part-time, or as needed. It is important to first identify health department staff who are responsible for CDR oversight and implementation.

CDR leadership and coordination group (LCG)

All health departments should establish a CDR LCG to oversee CDR activities. The group should include staff from multiple health department programs. Staff should have the expertise, authority, and skills to contribute to CDR LCG activities, which include:

- Planning for response

- Reviewing available data and prioritizing clusters

- Determining the amount and type of information to collect

- Identifying gaps and inequities in prevention and care

- Deciding on and implementing response actions

- Guiding, monitoring, and evaluating cluster response

- Ensuring data protections for CDR activities

We recommend the group meet routinely to review and prioritize clusters and determine how best to respond. For health departments without clusters or with low HIV rates, collaboration can occur during regular meetings or as needed.

At minimum, the CDR LCG should include HIV prevention, surveillance, and partner services leadership and staff. Group members should include staff with diverse expertise and leaders with authority to implement change across programs.

Example staffing model for CDR LCG

Program area

Responsibilities

HIV prevention

Identify and address gaps in HIV testing, pre-exposure prophylaxis/post-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP/PEP), syringe service programs (SSPs), and evaluate cluster response outcomes. Lead or co-lead CDR LCG.

HIV surveillance

Detect and monitor clusters, ensure data quality, and evaluate cluster response outcomes. Lead or co-lead CDR LCG.

Partner services and Disease Intervention Specialists

Guide partner notification and referrals for HIV testing, PrEP/PEP, sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing and treatment, and other services. Detect clusters and identify patterns among cluster and network members.

HIV care and treatment

Link people to clinical and supportive services. Identify and address gaps in HIV care and treatment.

Health department leadership with decision-making authority

Ensure support from all program areas for prioritizing cluster response activities, guide cluster prioritization, and coordinate cross-program efforts. Identify and guide interventions at individual, network, and system levels.

Other health department programs also have important roles in CDR, including sharing information and providing or addressing gaps in services. These programs may include sexual transmitted infections (STIs), hepatitis, substance use, housing, mental health, harm reduction, or informatics. Include people from these programs in the CDR LCG, as appropriate.

External partners are involved with CDR at different stages. These partners may include local health departments, state health departments, CBOs, HIV planning groups, health care organizations, or social service providers.

Surge capacity

To prepare for a scaled-up response, health departments should connect with their preparedness program to discuss options, processes, and training. In addition, health departments can identify staff to provide temporary assistance for surge capacity, including staff from other programs.

Developing and maintaining a CDR plan

In most cases, state health departments should develop a CDR plan for the entire state. The plan should be updated at least annually. CDC offers a CDR plan template that health departments can tailor. Components include:

- Defined roles for key internal and external partners

- Processes for cluster detection, prioritization, and monitoring

- Processes for deciding on and implementing investigation and response actions

- Plans for identifying more resources and staffing when response needs exceed routine capacity

Funding sources and flexibility

HIV clusters and outbreaks often highlight unmet service needs for preventing HIV and other related conditions. Thus, a variety of funding sources may be available to support CDR, including:

- CDC funding for HIV prevention and surveillance

- Public health funding for STIs, viral hepatitis, or other related conditions

- Behavioral health and opioid response funding

- Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program and Bureau for Primary Health Care funding

- Housing Opportunities for Persons With AIDS (HOPWA) and other U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) funding

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services (SAMHSA) funding

- CDC Public Health Emergency Preparedness funding

Depending on response needs, other funding from federal, state, or local governments, or public-private partnerships may be available.

Local populations experiencing rapid HIV transmission can change over time. Funding mechanisms should support starting or expanding activities for different subpopulations or geographic regions in cluster response.

Funding agreements with local health departments and community and health care partners should allow flexibility to shift resources when needed. For example, one health department offers mini-grants up to $10,000 for local health authorities and tribes to support CDR activities. Additionally, health departments should identify funding from multiple sources and talk with their CDC project officer if they need to redirect funds for cluster response.

Resources

- Developing an HIV Outbreak Response Table-Top Activity: A Starter Kit - visit https://nastad.org/resources/developing-hiv-outbreak-response-table-top-activity-starter-kit

- Community Response Planning for Outbreaks of Hepatitis and HIV among People Who Inject Drugs - visit https://www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/LENOWISCO-Project-Report_2018_FINAL.pdf

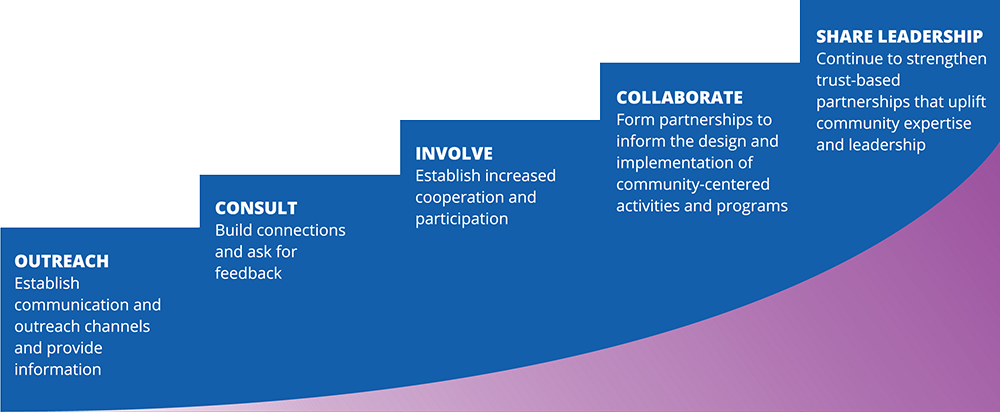

Engaging communities and partners is essential for CDR. This engagement helps health departments address community concerns and keeps partners and the public informed. Transparency provides a foundation for trust and collaboration, and community partners play a vital role in response.

People with lived experience, including people with HIV, have valuable insight into improving HIV prevention and care services. Community partners offering HIV and other support services have trusted relationships with the communities they serve. These organizations also understand their clients' lives and needs, including access to health and social services. With these insights, community partners can help health departments identify and address urgent needs.

Identifying community partners for CDR

Health departments should develop, strengthen, and maintain partnerships with community members and organizations for input on CDR. When planning for CDR activities, health departments should engage community partners, including:

- People with HIV and organizations that represent them

- People who would benefit from HIV prevention services and organizations that represent them

- Providers caring for people with HIV, including Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program recipients

- Community-based organizations (CBOs) that provide services to priority populations

- Tribal councils and communities

- HIV community planning groups, community advisory boards, or other local planning bodies

Depending on the local context, additional partners may include:

- Syringe services programs or other harm reduction services

- Behavioral health providers

- Academic institutions, including medical schools

- Housing support organizations

- Social service or other organizations that offer culturally and linguistically competent support services

Collaborating with other health departments can support multijurisdictional response and help people access HIV services across multiple areas.

Documenting community partners and resources that may be available can help identify existing strengths and highlight underserved populations or regions.

Planning and implementing CDR

After identifying community partners, health departments should work with them to develop or refine CDR plans and activities. Health departments should engage planning groups to ensure that CDR activities benefit people with HIV and those who need HIV prevention services. Your HIV community planning group should include representation from local communities experiencing rapid HIV transmission.

Health departments can further strengthen CDR activities by gathering input through a subcommittee or dedicated planning group session.

Considerations for engaging community planning groups about CDR

Who?

Include representatives from the key community partners you identified.

Where?

Consider whether to hold in-person, online, or hybrid meetings. In-person meetings may foster stronger relationship-building, while online meetings may have higher attendance.

When?

Outline a consistent meeting frequency (for example, monthly or quarterly). Consider more frequent engagement when establishing new relationships or during a cluster response.

How?

Outline a process for incorporating community feedback into CDR activities and reporting back. Plan resources to support ongoing engagement, including equitable compensation or travel support for people with lived experience.

What?

Discussions may include the purpose of CDR and how the health department conducts cluster detection and response activities, protects the data of people with HIV, and identifies and addresses community needs. See “Communicating with community partners” in the Communications section for guidance on what to discuss.

Meaningful community engagement includes a spectrum of activities, from education to relationship-building to routine partner or planning group meetings and collaboration. Increasing levels of engagement can build trust.

For example, health departments can:

- Educate service providers, organizations, and priority populations about the purpose and impact of CDR work.

- Host CDR-focused forums with community groups to strengthen relationships that can be helpful when a cluster or outbreak occurs.

- Collaborate with community partners for cluster investigation and response activities.

To evaluate your efforts, track engagement at these meetings. Use surveys or other tools to collect feedback that can help increase participation.

Building trust through transparent communication

Health departments should engage HIV community planning groups about CDR activities at least annually in the following ways:

Introduce the concept of CDR, including the purpose and activities, to HIV community planning groups.

Provide an update at least annually to HIV community planning groups on CDR activities. Include a short description of your routine cluster detection activities. This should include methods (for example, molecular and time-space), frequency of analyses, and number of concerning clusters identified. Updates should also describe the impact of CDR on public health activities and policy changes that address HIV service gaps.

Health departments without clusters can provide an overview of analyses conducted and plans to respond in case of a cluster.

When describing populations experiencing clusters and outbreaks, avoid stigmatizing language. If you discuss characteristics of people in clusters, explain that social and structural factors drive HIV disparities. That includes racism, xenophobia, stigma, discrimination, homophobia, poverty, unstable housing, and more.

Gather input from community planning groups and other partners on ways to improve response efforts, build trust, and strengthen relationships. Allow time for questions about CDR. Provide opportunities for members of planning groups to present. Consider getting input from the broader community, for instance, through interviews or focus groups. Some health departments have contracted with outside organizations to facilitate community engagement.

Although data show high levels of community support for HIV CDR, some have expressed concerns about aspects of this work. Engaging community partners about CDR can promote understanding and provide space to address these concerns. Discussing local HIV data protections and laws provides opportunities to strengthen data protections with community input.

Engaging community partners during a response

During a response, health departments should communicate with affected community members and the community partners who serve them. Sharing information is valuable and can help identify gaps in HIV services. Then, work with partners to address those gaps as part of the cluster response. This engagement should be collaborative and continue throughout the response.

Resources

Resource and Community Asset Mapping

- Chapter 3: Assessing Community Needs and Resources |Section 8: Identifying Community Assets and Resources | Community Tool Box - available at https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/assessment/assessing-community-needs-and-resources/identify-community-assets/main

Community Engagement Guides

- Community Engagement Playbook

- Re-envisioning Community Engagement: A Practical Toolkit to Empower HIV Prevention Efforts with Marginalized Communities - available at https://nastad.org/resources/re-envisioning-community-engagement-toolkit

Engaging People with HIV

- Meaningful involvement of people with HIV/AIDS (MIPA) - available at https://www.seroproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Meaningful_Involvement_of_People_with_HIV_AIDS_MIPA.pdf

- Methods and Emerging Strategies to Engage People with Lived Experience

Community Engagement Examples

- HIV Outbreak: Cabell County, West Virginia - available at https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(21)00381-0/fulltext

- CDR Community Spotlight: Detroit, Michigan

HIV cluster detection identifies communities affected by rapid HIV transmission. Health departments can identify HIV clusters through analyzing surveillance data. Additionally, HIV clusters can be identified by providers, partner services and frontline staff, and community members. These methods complement each other.

Health departments should analyze HIV surveillance data monthly to quickly identify and monitor HIV clusters. In most cases, state health departments should conduct these analyses on behalf of local health departments. Analyses should include time-space and molecular cluster detection. Low morbidity jurisdictions (areas that have low numbers of HIV diagnoses) may conduct analyses as needed when new diagnoses or molecular sequences are reported.

Time-space analysis

Time-space analysis identifies increases in HIV diagnoses in a particular geographic area or population. CDC provides software programs that health departments can use or adapt for routine analyses. Health departments can also develop their own approaches to time-space analysis.

Increases in new diagnoses may or may not reflect rapid HIV transmission. Time-space increases need further investigation because they may indicate one large cluster, many small clusters, or an increase in HIV testing that has led to new diagnoses of older infections.

People within the network experiencing rapid transmission might not be part of the identified time-space cluster. This can occur if they have undiagnosed HIV or the network expands beyond the identified geographic area.

Molecular cluster analysis

Health departments conduct molecular analysis using a portion of the genetic sequence of HIV that comes from HIV drug resistance testing. These data are used to monitor HIV drug resistance and detect rapid HIV transmission. Rapid HIV transmission is evident when molecular data show groups of extremely similar HIV genetic sequences.

People with HIV in the network experiencing rapid transmission might not be included in the identified molecular cluster because:

- They haven’t received a diagnosis yet.

- They didn’t receive an HIV drug resistance test, or the test did not produce a result.

- Their molecular test result wasn’t sent to the health department.

Molecular analysis examines the genetic sequence of the virus, not the person. Many people may have similar HIV genetic sequences. Therefore, when two people have similar HIV genetic sequences, it doesn’t mean one person passed HIV to the other.

There are different approaches to analyzing molecular data to identify clusters, and not all focus on identifying rapid transmission. CDC’s approach identifies clusters of rapid transmission, and the most concerning of these are known as “national priority clusters.” Health departments should respond to all national priority clusters. Health departments may also respond to clusters meeting local criteria, depending on their capacity.

CDC has provided Secure HIV-TRACE, a secure, web-based application for health departments to use for molecular cluster detection. Secure HIV-TRACE identifies national priority clusters and other concerning clusters. Information on how health department staff may access Secure HIV-TRACE can be found in this video.

HIV and STI partner services

Partner services staff interview people newly diagnosed with HIV or other STIs to connect them and their partners with services. Staff can notify partners of possible exposure, get them tested, and link them to prevention and care. Because partner services staff work closely with local communities, they may notice patterns or increases in HIV diagnoses.

Health care providers and community members

Clinical providers or community members may help identify HIV clusters. Observed increases in HIV diagnoses require further investigation to determine whether they reflect transmission increases in a community.

Detecting clusters across jurisdictions

CDC conducts routine analyses of national HIV surveillance data to identify clusters of rapid transmission. While health departments can identify clusters within your jurisdiction, CDC can find clusters affecting multiple jurisdictions.

The importance of complete, timely, and accurate data

Health departments can work to increase the percentage of providers ordering HIV drug resistance tests and laboratories reporting sequence results. These tests are important for individual health and can also help detect and improve community response to HIV clusters. Increasing reporting speed and accuracy can improve cluster detection capabilities.

Health departments can contact your HIV Surveillance Branch Project Officer for technical assistance related to data completeness, timeliness, and accuracy.

Detected clusters are only a part of the network

Many factors affect how much of the larger network public health partners detect. These include:

- Cluster detection method

- Availability of HIV testing programs

- Access to HIV care

- Data completeness

Once a cluster is detected, collecting additional information can help to identify more of the network and highlight service gaps. This information can help improve prevention and care services and better meet the needs of people in the affected network. It can also help reduce HIV transmission.

Health department surveillance staff should refer to the “Technical Guidance for HIV Surveillance Programs” document provided by the HIV Surveillance Branch for more information on HIV cluster detection.

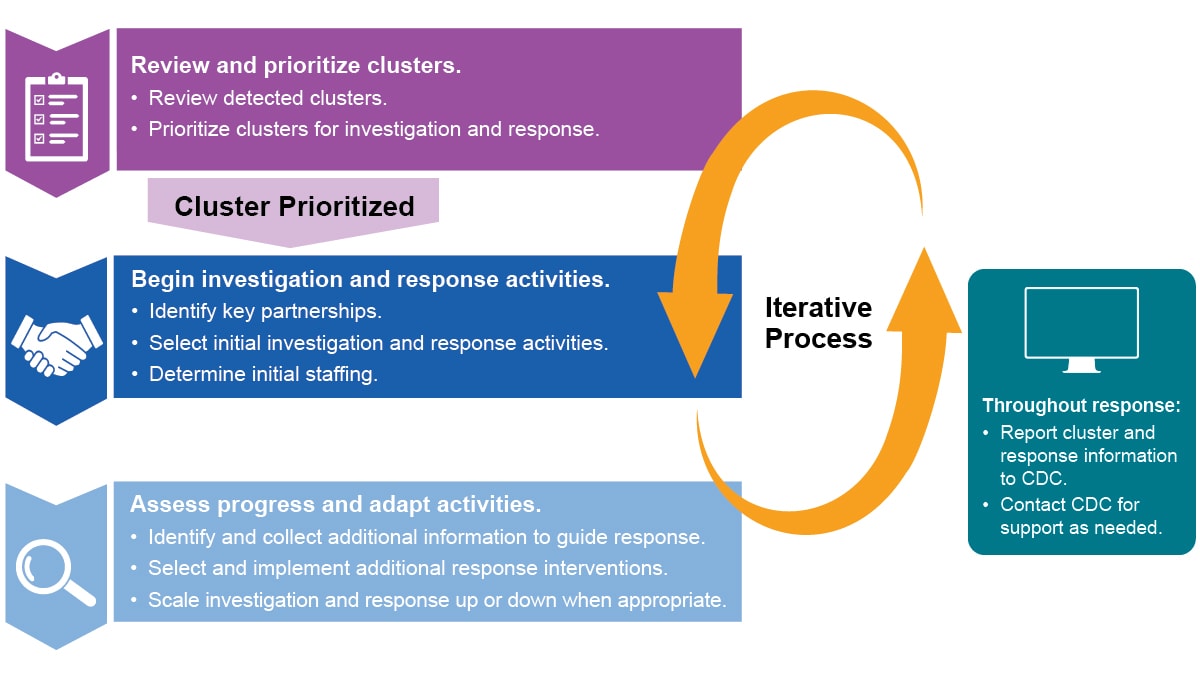

Reviewing and prioritizing clusters can help health departments understand the level of investigation and response needed. It can also help determine where to focus resources.

Convene group to review and prioritize clusters

Health departments should convene a CDR leadership and coordination group (LCG) to review and prioritize clusters. The group should meet at least monthly, unless there are no new clusters and no clusters being monitored, and should:

- Review available data

- Prioritize clusters

- Determine the amount and type of additional information needed to guide response

- Decide on and implement response actions

The CDR LCG can scale response activities up or down based on their level of concern, local epidemiology, and available capacity and resources. During scaled up response activities, consider including additional staff in CDR LCG meetings. CDC can also provide technical assistance with prioritizing clusters. Health departments should contact their assigned Detection and Response Branch epidemiologists for assistance.

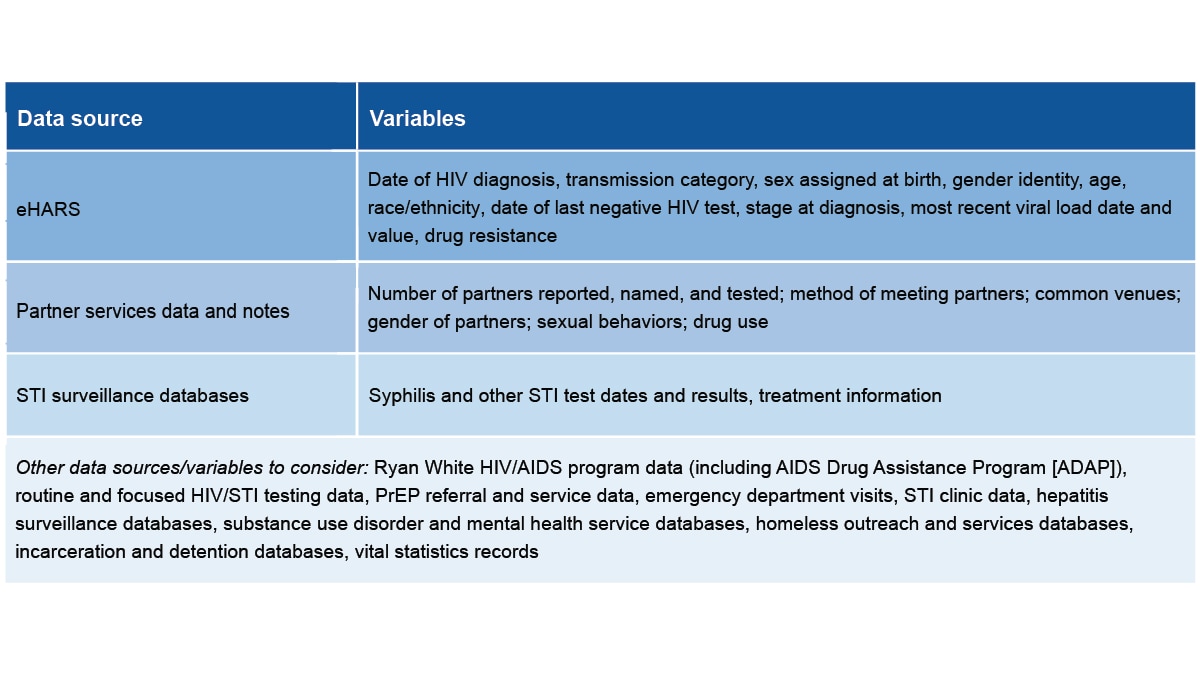

Compile and review available data

Health departments should compile and review data from multiple sources to determine their level of concern. The potential for cluster growth and negative health outcomes are important factors in prioritizing clusters for response. Health departments can use their comprehensive HIV CDR plan to guide the review process. The plan should include which staff will lead the process and which data sources are available.

Monitoring and reviewing clusters should be an ongoing process. New information collected during an investigation and response might change the level of concern. During review, health departments can consider which response approaches to prioritize to improve HIV care and prevention and reduce transmission. Ongoing review will also help determine whether a cluster response should continue. Even after response efforts end, continued monitoring can determine whether response efforts should resume.

Cluster case definition

When planning to review and prioritize a cluster, it is helpful to create a cluster case definition. A cluster case definition describes specific criteria for including someone in a cluster. Criteria can include a variety of information, such as year of diagnosis, race or ethnicity, or geographic area. A cluster case definition helps with estimating and assessing the cluster's size and growth, and prioritizing response.

Cluster case definitions can be especially important for time-space clusters because the inclusion criteria are often less specific than for molecular clusters. Cluster case definitions are also helpful for molecular clusters. In this case, they can include people who are part of a network but not identified in the molecular cluster. Cluster case definitions may change as more data become available.

Example Cluster Case Definitions

- Molecular cluster case definition: A person with a confirmed HIV diagnosis on or after January 1, 20XX who:

- is a member of XXX molecular HIV cluster using a 0.5% genetic distance threshold; OR

- has had sex or shared drug injection equipment with a cluster member.

- is a member of XXX molecular HIV cluster using a 0.5% genetic distance threshold; OR

- Time-space cluster case definition: Confirmed HIV diagnosis on or after January 1, 20XX in a person who:

- has a history of injection drug use; AND

- lived in X county at the time of diagnosis; AND

- has had sex or shared drug injection equipment with a cluster member.

- has a history of injection drug use; AND

Data sources

Relevant data sources include HIV surveillance, prevention, and care; partner services; sexually transmitted infections (STI); and other related program data. Health departments should have a plan to securely compile the existing data. This can be done manually or by creating a process or product that automatically combines data from different sources. Health departments can implement a dashboard or other method that allows for analysis, integration, visualization, and secure data sharing. Because compiling data can be complex, staff might need to consult with their data management or IT programs for support.

Summarize cluster data

Once the data are compiled, the CDR LCG should review and discuss the information. Consider creating a narrative description or a line list for the cluster to summarize the data.

Cluster narrative

It is often helpful to create a narrative from the compiled data to better understand the network, what people in the cluster have in common, and what additional information would be most useful. This can help guide cluster prioritization.

Example Cluster Narrative

- We identified a molecular cluster of 12 people with HIV, within the 18-month period ending December 2023. The cluster primarily included young Black gay and bisexual men in a rural part of State X. Among people in the cluster:

- 7 of 12 people with testing history data have evidence of infection within 12 months of diagnosis.

- All sequences have K103N mutation.

- 6 of 12 people have no evidence of viral suppression.

- 7 of 12 people with testing history data have evidence of infection within 12 months of diagnosis.

- Partner services conducted for 8 of 12 people in the molecular cluster identified 3 named partners: 1 person with newly diagnosed HIV, 1 person with previously diagnosed HIV, and 1 person who tested negative.

- People in the cluster identified large numbers of anonymous or marginal partners. Multiple cluster members identified a dating app X as the primary way they meet partners.

- The scope of the cluster and network are likely much larger than identified through molecular analysis and available partner services information.

Line lists

Line lists are tables with key information about each person in a cluster or associated network. Typically, each row represents one person, and each column represents the data variables included in the review process. This helps summarize information and guide prioritization. However, health departments must limit access to ensure that individual-level information is not shared inappropriately. Even line lists that don’t include personally identifiable information can include sensitive information.

Prioritize clusters for response

Once the data have been summarized, health departments should prioritize clusters to determine whether investigation and response is warranted. The questions to consider may vary depending on how cluster detection occurred—through time-space analysis, molecular detection, or other methods. Health departments should prepare criteria in advance to guide prioritization and describe potential investigation and response actions.

Questions to consider when developing prioritization criteria

What is the local epidemiology?

Factors to consider include:

- How significant is the increase in new diagnoses compared to the baseline?

- Are diagnoses occurring in a certain geographic area?

Are there alternative explanations for an increase in diagnoses?

This is important for clusters detected through time-space or other non-molecular methods. Consider other potential reasons for observed increases in diagnoses, such as:

- Changes in data quality

- Increases in testing

- Demographic changes

- Policy changes

What is the potential for ongoing transmission?

Factors that raise concern for ongoing transmission include:

- Social determinants of health that might limit access to HIV prevention and care (for example, unstable housing, history of incarceration)

- Injection drug use

- Large numbers of sex partners

- People who have high viral loads or are not in care

- Multiple people who have acquired HIV recently (for example, acute or stage 0 infection at diagnosis)

- Limited or inadequate HIV prevention and care services in the area

- Coinfection with other STIs or hepatitis

Is there a strong understanding of the network involved in this cluster?

Further investigation may be warranted if:

- The health department is experiencing challenges interviewing people in clusters and conducting partner services

- People in clusters report large numbers of anonymous partners

- HIV testing is limited, suggesting that the network is substantially larger than what has been detected

- For molecular clusters, sequence completeness is low, meaning the cluster is likely much larger than it appears

Do people in the cluster have the potential of experiencing poor health outcomes?

Factors that can indicate potential for poor health outcomes among cluster members include:

- Medically underserved populations (for example, youth or people experiencing homelessness)

- People experiencing discrimination due to race or ethnicity, sex, sexual orientation, or immigration status

- Women of child-bearing age

- Late diagnoses due to limited testing and care access

- Diagnoses at locations such as emergency departments or correctional institutions

- Identified HIV drug resistance

The CDR LCG should establish, implement, and revise criteria for levels of concern and associated responses.

Clusters and networks often cross jurisdictional borders. Someone may live in one jurisdiction and have partners or seek care elsewhere. Cluster review, investigation, and response should include all people linked to the network, regardless of where they live. This may require collaboration across multiple health departments.

Ongoing reporting, review, and prioritization

The CDR LCG should discuss and review clusters at least monthly. As more data become available, clusters may increase or decrease in priority. As the priority level for a cluster changes, investigation and response can be scaled up or down. Low-priority clusters may warrant monitoring even if they do not need active investigation and response efforts initially.

Health departments should report cluster investigation and response activities to CDC by submitting cluster report forms (CRFs) quarterly. These forms can facilitate structured communication with Detection and Response Branch epidemiologists about ongoing response efforts. These reports are also important for national evaluation of CDR. If a cluster remains consistently low priority over time, the health department can end response activities and stop submitting CRFs.

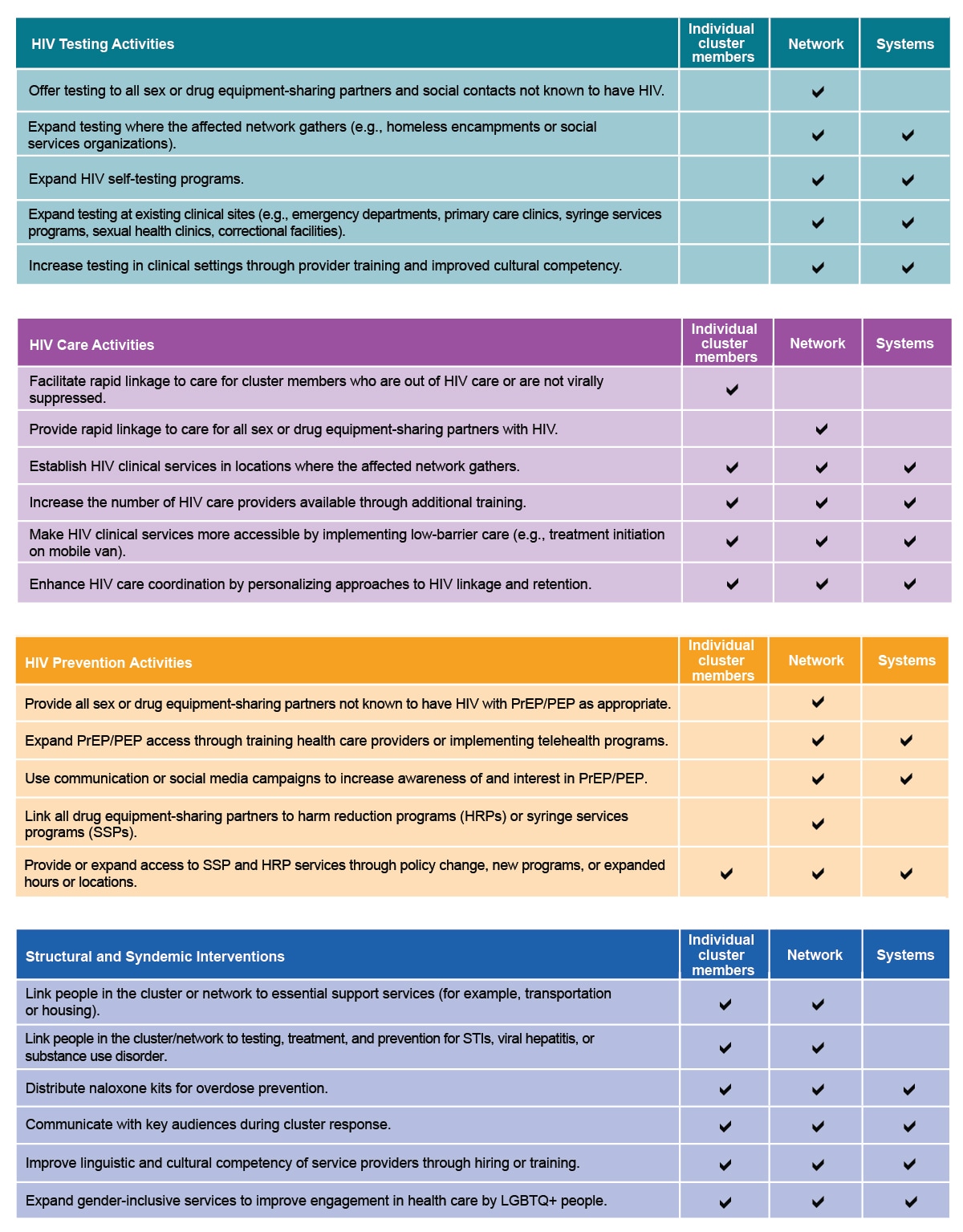

Health departments should investigate and respond to prioritized clusters to prevent ongoing rapid HIV transmission. Investigation involves gathering additional information to understand affected people’s needs. Effective response measures should be tailored to address these needs.

Because clusters are part of larger networks and result from gaps in prevention and care, health departments should implement response activities at individual, network, and systems levels.

Begin investigation and response

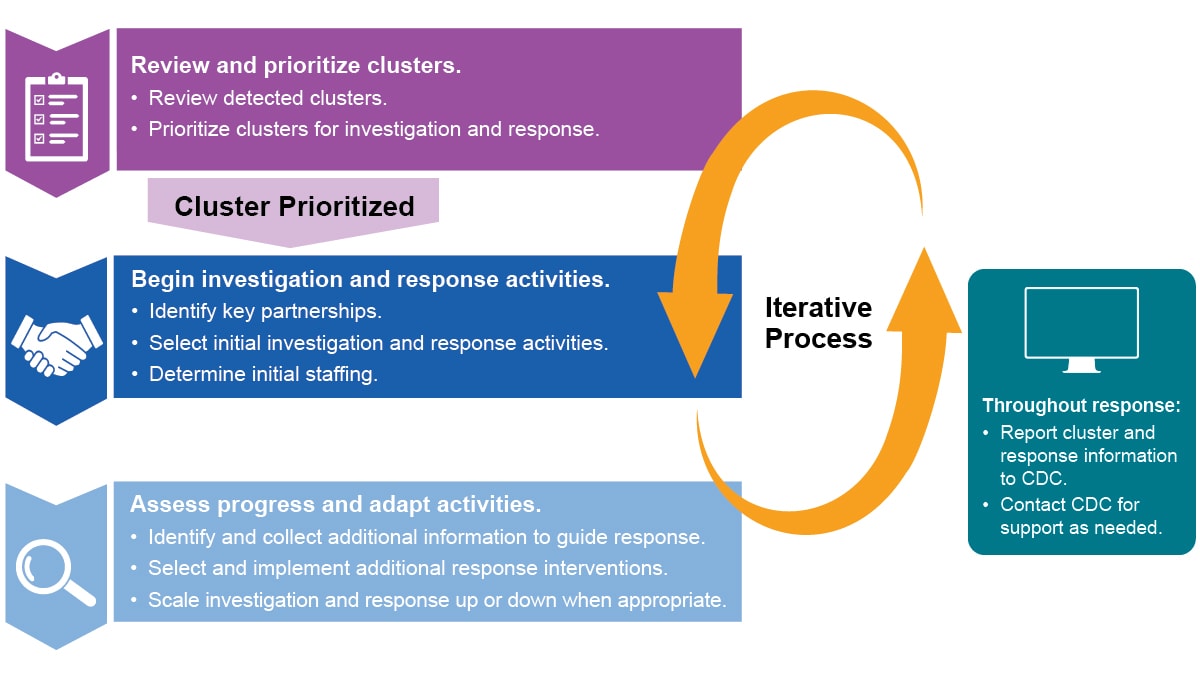

Once the CDR LCG has reviewed and prioritized clusters, they should begin investigation and response activities. They should guide the following steps, which may be done at the same time:

- Review available information. Revisit data sources to learn how transmission may be occurring, and which communities may be affected.

- Identify partners for response. Work with affected community members, providers, community-based organizations, local health departments, and local planning groups on response activities.

- Share cluster-level information with partners. Summary information will help partners better understand what services are currently available and where gaps are occurring.

- Select and implement response strategies. Tailor strategies at individual, network, and systems levels to improve response effectiveness.

- Set specific goals for each cluster. Health departments should set specific, measurable targets to guide response and future scaling up or down of response activities. For example:

- Linking a specific number of people to care

- Testing a certain percentage of the known network

- Increasing the number of pre-exposure prophylaxis/post-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP/PEP) providers

- Linking a specific number of people to care

- Discuss staffing and funding needs. Consult your CDR plan to fill necessary roles for investigation and response activities. In addition, determine the need for specific skills or expertise (for example, language skills or knowledge of specific populations).

- Report the cluster. Report cluster investigation and response activities to CDC through regular submission of CRFs.

Assess progress and adapt response

The CDR LCG should meet regularly to:

- Assess progress toward goals for cluster response.

- Identify what additional information is needed and how to gather that information.

- Build upon response efforts by selecting and tailoring additional response strategies at individual, network, and systems levels.

Collect additional information

The CDR LCG should consider what additional information they need to guide response activities. This may include exploring social factors (for example, drug use patterns) or structural factors (for example, access to drug treatment). Activities to collect this information can include:

- Examining clinical data.

- Holding focus groups with community partners.

- Conducting expanded partner services interviews or provider surveys.

- Implementing expanded partner services or social network strategies to identify more network members and assess their needs.

- Reviewing existing policies to identify areas for improvement.

- Assessing access to HIV prevention, care, and essential support services for affected populations through phone calls or web searches.

Additional response activities

The CDR LCG should select response activities at individual, network, and systems levels tailored to the cluster.

Systems-level changes are particularly important, and often require significant investment because they have broad impact and lead to lasting change.

Many of these activities affect more than one level. For example, a systems-level policy change should improve services to a network and for individual cluster members.

Partnerships and collaboration with community members, providers, and local organizations are essential for activities to succeed.

The HIV CDR Science Brief provides detailed examples of the above activities in past cluster responses.

Scaling up investigation and response

Different aspects of cluster investigation and response can be scaled up depending on the needs of the affected network.

Assess needs. Reasons why a health department may scale up response activities:

- The cluster meets pre-determined criteria (for example, high number of recent diagnoses or recent transmission among a specific population).

- Response activities exceed the capacity of staff initially assigned to support the response.

Determine activities to increase response capacity. Some examples include:

Activating surge staff or partnerships (for example, adding a public information officer for communications support).

- Increasing community collaboration and partnerships.

- Identifying supplemental funding or redirecting existing funds.

- Activating an Incident Management or Incident Command System within the HIV program, agency, or state-wide.

Communicate with staff and community partners during scaled up response. CDR staff should provide regular updates to local and state leadership, response staff, community partners, and CDC and other federal agencies. These staff and partners can also provide feedback on escalated response activities.

Scaling down or ending response

When cluster data indicate significant progress toward goals, consider scaling down some or all response activities.

Factors to consider:

- Evidence that transmission has declined, and HIV prevention and care have improved. This can include:

- A reduced number of new diagnoses over time, particularly in the setting of strong HIV testing coverage.

- High rates of people being in care and virally suppressed.

- A large percentage of people in the network have received partner services interviews. Reported contacts have been tested and referred to services as needed.

- A reduced number of new diagnoses over time, particularly in the setting of strong HIV testing coverage.

- Cluster no longer meets priority criteria.

- Community partners express support for scaling down response activities.

Activities when scaling down or ending a response should include:

- Determining a threshold for again scaling up the response.

- Planning for key response activities that should continue as routine practice.

- Communicating to partners that the scale down is occurring and discussing which activities should be ongoing.

Report response activities to CDC. CDR activities should be reported to CDC. CDC Detection and Response Branch epidemiologists can also provide advice and support for investigation and response activities.

Evaluate response activities

Consider evaluation during and after response to gather lessons learned and opportunities for improving future responses. Evaluation can show whether the response addressed prevention and treatment gaps. Metrics to examine can include:

- New HIV diagnoses identified mainly through active investigation and intervention activities, such as partner services and testing.

- Implementation or expansion of additional services.

- Effective policy changes that address barriers and strengthen services for affected communities.

Monitor cluster after response ends. After investigation and response activities have ended, continue to monitor for any changes. New cluster growth might indicate a need to reopen a cluster response.

Contact CDC for support

CDC may be able to assist health departments with the planning and implementation of investigation and response activities. Health departments should reach out to their assigned CDC Detection and Response Branch epidemiologist to discuss their needs and interests.

Evaluating CDR activities can help health departments assess whether their actions have improved HIV prevention and treatment services. Reporting CDR activities and outcomes allows CDC to understand how health departments are implementing CDR.

Health department evaluation of CDR

Evaluation can help health departments assess processes and outcomes of CDR, highlight lessons learned, and identify opportunities for improvement. Health departments can also evaluate the effects of a response on system-level factors, including stigma, social determinants of health, and service gaps.

Evaluation of routine processes, such as cluster detection and community engagement, can occur regularly. This evaluation can include assessing whether activities were conducted as planned and identifying opportunities for improvement.

Evaluation of investigation and response outcomes will vary in scale and type depending on the activities implemented, so should be tailored for different responses. Evaluation of response activities can help answer:

- What changed as a result of the response activities?

- Which activities were or were not successful?

- What could we do better in the future?

With any approach, first consider the metrics and goals determined during the investigation and response. Evaluation questions can include:

- To what extent were new HIV diagnoses in the cluster identified through CDR activities?

- Which of the pre-determined response goals were accomplished?

- To what extent were additional services implemented or expanded?

- To what extent were policy changes put in place to address barriers and strengthen services?

Once you have described the outcomes of the investigation and response, you can then explore the reasons behind them:

- What key factors led to success in reaching the response goals?

- What key challenges prevented certain goals from being met?

Finally, evaluation findings should inform responses to future clusters. Consider how to apply the lessons learned from your evaluation:

- What would we change when responding to future clusters and outbreaks?

- What changes could we make to routine prevention, care, and treatment programs to prevent future clusters or outbreaks?

Reporting CDR activities

Reporting CDR activities to CDC is essential for national CDR evaluation. Health departments should report cluster investigation and response activities to CDC by submitting cluster report forms (CRFs) quarterly. CDC uses this information to monitor CDR activities and identify successes and challenges across health departments.

CRFs help CDC understand priority clusters at a national level and assess cluster growth. They also provide information on individual, network, and system-level outcomes. The data reported do not include individual-level information or identifiers.

Components of a CRF include:

Examples of data collected in CRF

Detection methods

- Cluster detection date and method

- County of alert (if using time-space or other approaches)

Data reviewed

- Checklist of additional data sources the health department reviewed

Size of cluster and larger network

- Number of people in the cluster and larger network

Other characteristics

- Common venues, or physical and virtual sites

- Other factors that might be associated with increased HIV transmission

Health outcomes

- Evidence of recent viral suppression

Outcomes for partners

- Number of partners tested and their test results

Key findings

- Narrative summary of key findings describing individual, network, and systems-level activities

- Level of health department concern for this cluster

Health departments should submit an initial CRF following cluster detection and submit follow-up forms quarterly. Health departments should submit forms yearly for ongoing clusters, and closeout forms when a response ends.

In addition to the information in the CRF, both CDC and health departments use the Enhanced HIV/AIDS Reporting System (eHARS) to evaluate outcomes. eHARS is a secure, browser-based, CDC-developed application that assists health departments with reporting, data management, analysis, and transfer of data to CDC. Health departments should enter cluster IDs into eHARS.

For CRF and eHARS cluster ID submission guidance, please refer to CDC's HIV Surveillance Branch SharePoint Site. CDC Detection and Response Branch (DRB) epidemiologists can also provide advice and support on evaluation and reporting. Health departments should contact their assigned DRB epidemiologists for further consultation.

Responding to HIV clusters requires inclusive, non-stigmatizing communication with community partners, providers, people affected by rapid HIV transmission, and the public. Communicating about CDR activities includes sharing information and understanding community and partner perspectives. This two-way communication can help build trust and strengthen relationships between your health department and partners.

Principles for communicating about CDR

Use a health equity lens.

- Consider the potential positive and negative effects of proposed messages.

- Highlight that social and structural factors such as racism, stigma, homophobia, and poverty contribute to disparities in HIV transmission.

- Communicate how CDR is working to address health inequities, directing resources to groups most affected by rapid HIV transmission

Reduce stigma.

- Communicate about HIV transmission in a way that does not stigmatize people or their behaviors.

- Avoid unintentionally blaming people for their circumstances, especially people experiencing rapid HIV transmission.

- See CDC's Ways to Stop HIV Stigma and Discrimination for more information.

Avoid dehumanizing language.

- Use people-first language. Say "people with HIV" instead of "cases" or "HIV-positive people." Say "people who could benefit from HIV services" instead of "HIV-negative people."

- Avoid using acronyms. For example, use "gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men" instead of "MSM."

- Remember that when discussing a cluster or outbreak, you are referring to people. When appropriate, say "people in the cluster" rather than just "the cluster."

Use plain language.

- Plain language makes it easier for everyone to understand and use health information. This is true for all audiences, including the public, health care providers, and community partners.

- Some CDR terms have different meanings for public health staff than for the public. Adapt messaging to your audience's needs. For example, the term "surveillance" means something different outside of public health settings. Depending on your audience and the purpose, consider using "HIV data" or "monitoring."

- See CDC's Health Literacy website and Everyday Words for Public Health Communication for more information.

Collaborate with partners and community members to incorporate local communication preferences.

- Get input from your intended audiences on preferred terms. For example, health departments have options when referring to clusters. "Cluster" and "outbreak" are sometimes used interchangeably, without a clear distinction. Some community partners have shared that terms like "network" feel more inclusive and less stigmatizing. Some health departments have renamed their local CDR activities to incorporate community input.

- Create culturally appropriate materials in the preferred languages of your audience. Have native speakers help develop these materials.

- Consider peer educators or others who can serve as community liaisons to share information about CDR and provide community perspectives.

- Use communication channels (for example, newsletters, websites, or social media) trusted by the affected network.

- Educate providers, partner services staff, and community organizations so that they can answer questions about CDR from people in networks.

- CDC's Stories from the Field stories are also a resource to explain CDR.

Communicating about routine CDR activities to increase transparency and collaboration

CDR includes many different public health activities. Communicating about these activities to various audiences and partners can be challenging.

Communicating with the public

Health departments should share information about their routine CDR activities. Include how you conduct cluster detection, the number of concerning clusters, and how the health department protects people's data. If applicable, include a summary of response activities and outcomes. You can share information in an annual report or public dashboard.

Health departments should refer to the HIV Surveillance Branch "Technical Guidance for HIV Surveillance Programs" for more information.

Communicating with community partners

Communicating proactively with key communities about CDR can increase trust and transparency. Health departments should engage HIV planning groups and other community partners, including providers, to discuss CDR. These discussions may include the purpose of CDR and how the health department:

- Conducts cluster detection activities (molecular and time-space detection, how often, etc.)

- Responds to clusters and adapts services based on needs

- Protects the data of people with HIV

- Identifies and addresses community needs

- Understands community preferences for communication and feedback

Some of this information may be included in annual reports or public dashboards, but additional discussion with community partners enables feedback to understand and address concerns.

Medical and service providers have important roles in answering questions and addressing concerns about CDR. Ensure that key partners offering HIV prevention and care services are aware of CDR activities in your jurisdiction. This way, they can answer questions clients might have and refer them to more resources.

Communicating during a response

When responding to an HIV cluster or outbreak, consider how to communicate relevant information with key audiences. Proactive, ongoing communication is important to reach people affected by the cluster and keep the public informed. Effective communication can empower people to improve their health, help partners understand the situation and their role, and fight misinformation.

During a response, your communication strategy should reflect a strong understanding of your community. Early in the planning process, engage community partners who reflect or serve the affected community to gain a better on the ground perspective. Consider ways to partner with them throughout your response to craft messages and plan other response activities.

Different audiences have varying communication needs. Common audiences can include:

- People affected by the cluster or outbreak, who may benefit from awareness and education about HIV prevention and care services.

- The public, which may benefit from prevention and care messages, communication about response activities, and how to access services.

- Service providers, who may be well-positioned to support response activities as partners.

- Decision-makers in the community, who can play a role in response success.

- Media, which can assist with communicating information to the public.

Developing messages

People with HIV, community partners, and providers can help you understand the most effective ways to communicate during a response. This includes developing messages that specifically address community needs. Qualitative interviews or focus groups can show you what messages might work best and how to share those messages. Building trust with partners, community leaders, and the public is key to a successful response.

Stating that rapid HIV transmission is occurring can increase transparency and help people understand what is happening in their community. Minimize stigma and avoid blaming the people in the cluster. Consider the right term for your situation (for example, cluster, network, outbreak, or something else). Whichever term you use, describe how you are taking action to address rapid HIV transmission. For example, "HIV diagnoses are increasing in our community. We are taking action to help people with HIV and others in their networks get the services they need." Throughout the response, reevaluate and modify key messages to address the changing situation.

Relevant topics for response messages include information about HIV testing, prevention, treatment, and stigma reduction. CDC's Let's Stop HIV Together materials communicate about these topics. These resources are free, and many are adaptable for health department use. Your health department may also have communication materials that you can use in case of a cluster or outbreak. Proactive, routine communication about HIV prevention and care helps connect people with needed services.

To reach the people affected by an HIV cluster, consider where they spend their time and how they connect. Communication approaches might include:

- Posters, billboards, palm cards, or other printed resources to encourage testing, treatment, and prevention in community centers, bars, or neighborhoods

- Online marketing such as social media ads

- Geotargeted, tailored messaging on hook-up or dating apps

Providers are a trusted source of information.

Health care providers can serve as a bridge between the health department and people who use HIV services. Communicating with providers about a response can include clinician or partner calls, trainings, health alert networks, and dear colleague letters. CDC provides information on effective messaging during outbreak responses. Particularly in areas where HIV is not common, local provider groups may benefit from trainings about HIV or CDR.

Resources

CDC resources

- Communicating During an Outbreak or Public Health Investigation

- Crisis & Emergency Risk Communication (CERC)

- Health Equity Guiding Principles for Inclusive Communication

- A Guide to Talking About HIV

- Communicating During an HIV Outbreak Among People Who Inject Drugs in West Virginia

- Division of HIV Prevention Printable Outreach Materials

Other resources

- Delaware Division of Public Health: The Importance of Communication Before and During a Public Health Emergency – PMC - available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8352364/

- The National Academies of Sciences: Building Communication Capacity to Counter Infectious Disease Threats - available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK436831/

Public health data are the foundation of public health practice and essential to helping people live healthy lives. CDR data help identify rapid HIV transmission and improve services at individual, network, and systems levels.

Protecting people's privacy and confidentiality is an essential part of using public health data. Federal, state, and territorial laws and policies protect public health data as do health department policies and processes. Some cities have additional data protections.

Protecting data during CDR activities

Follow federal, state, territorial, and local data protection guidelines

CDC has strong security measures to ensure the privacy and confidentiality of people with HIV. An Assurance of Confidentiality provides strong protection for HIV public health data at CDC. This assurance guarantees that information is used only for the purposes stated and is not disclosed or released without consent.

State, territorial, and local health departments must comply with CDC Data Security and Confidentiality Guidelines. Health departments should regularly reassess data protections and enhance policies and procedures, ensuring that CDR-related data are strongly protected.

Ensure strong data protections

Key data protections partners include health department legal counsel, information technology staff, privacy officers, and the overall responsible party. HIV surveillance and prevention programs should collaborate with these partners to develop a shared understanding of:

- Processes for reviewing data release requests, including staff roles and responsibilities.

- Protections to prevent release of HIV public health data for non-public health purposes (for example, criminal or immigration-related uses).

- Opportunities to strengthen these protections.

- Interpretations and implications of state or local laws and policies governing data protections and release.

Health department legal counsel has an important role in interpreting laws and policies governing data protections and release. Interpretation should aim to protect the privacy and confidentiality of people with HIV. Health department legal counsel should partner with state or local government counsel to maximize protections, especially when responding to requests. Community partners can also provide input to strengthen data protections.

Provide staff training for people working with HIV data. Training can cover the importance of data protections and privacy, including sensitivities around HIV cluster data.

Use public health data only for public health purposes

Health departments shouldn't release identifiable HIV data for non-public health purposes, except where required by law. Even if required by law, only the minimum required information should be released.

For more information, see Standard 3.4 of the CDC Data Security and Confidentiality Guidelines.

Carefully consider whether to share data for research purposes

Health departments should discuss with HIV planning groups whether, and under what circumstances, to share HIV sequences for research purposes. Research conducted with HIV public health data should serve a legitimate public health purpose.

When considering sharing sequences for research purposes, health departments should engage institutional review and data governance boards. Ensure they are aware of the ethical and community considerations regarding HIV sequences. If health departments then choose to share even deidentified sequences with academic partners for research purposes, consider obtaining individual informed consent. Some health departments have decided, following their local community's input, not to share even deidentified sequences externally.

For more information, see Standard 2.4 of the CDC Data Security and Confidentiality Guidelines.

Don't release data to public databases

CDC does not release HIV sequence data to GenBank or other public sequence databases. Health departments and their academic partners should never release HIV sequence data collected through HIV surveillance publicly. Do not submit even deidentified HIV sequence data to public databases without consent from each person with a sequence included.

Protect privacy when communicating about CDR

Communicating with partners and the public is an important part of CDR work. Before communicating about clusters, consider what information each audience needs to take appropriate action.

Protecting privacy when communicating with the public

When communicating with the public about clusters, do not share individual-level data. Only share information describing clusters or groups experiencing rapid transmission, not individuals. Use caution to avoid any stigmatizing language.

Protecting privacy when communicating with partners

When discussing cluster-related data with non-health department partners, protect the privacy of people with HIV. Unless data sharing agreements are in place, only share cluster- or population-level data. Cluster-level data discussed with partners should be limited to the information necessary to understand service gaps and potential interventions. Also consider population size and cell counts to ensure confidentiality of people represented in data. Avoid using molecular network diagrams, which are easy to misinterpret, for communicating with partners.

Data sharing for response

During a response, health departments may need to share data with other local health departments, neighboring jurisdictions, or community-based organizations. Secure data sharing can support collaboration to conduct testing, partner services, and linkage to care or other services. When considering sharing, ensure that other organizations have data security standards that meet CDC Data Security and Confidentiality Guidelines (see Standard 3.3). Data sharing agreements (DSAs) or memoranda of understanding (MOUs) can provide important protections.

Data sharing with other health departments

Data sharing with neighboring health departments can ensure continuity of prevention and care services where people frequently cross state lines. Secure sharing can also support response to multijurisdictional clusters. Health departments may have DSAs or MOUs in place with neighboring state, local, and territorial jurisdictions. When establishing agreements for secure data sharing, health departments should consider data protection laws and processes in the neighboring jurisdictions.

Data sharing with community-based organizations

Community-based and health care organizations can be important partners in conducting response activities. Many activities can be conducted without a need for person-level data. If person-level data (for example, a line list) must be shared for response, health departments must establish DSAs or MOUs. Establishing DSAs or MOUs with key partners in advance can support rapid response to clusters. Contract mechanisms or agreements can strengthen oversight and compliance with data protections guidelines.

Resources

CDC resources

Other resources

- HIV Data Privacy and Confidentiality: Legal and Ethical Considerations for Health Department Data Sharing - available at https://nastad.org/resources/hiv-data-privacy-and-confidentiality-legal-ethical-considerations-health-department-data

- U.S. HIV Data Protection Landscape - available at https://nastad.org/resources/hiv-data-protection-landscape

- Data Use and Non-Disclosure Agreement Concerning the Access to Protected Health Information or Other Confidential Information - available at https://www.michigan.gov/-/media/Project/Websites/mdhhs/Folder2/Folder79/Folder1/Folder179/Data_Use_and_Non_Disclosure_Data_Disclosed_to_MDCH_Trauma_Registry_Final.pdf?rev=a39f39bb9db94ad092285727fb2cc152

- Cross-Jurisdictional Data Sharing: Legal, Practical, and Ethical Considerations for Improved Infectious Disease Cluster Response - available at https://nastad.org/resources/cross-jurisdictional-data-sharing-legal-practical-and-ethical-considerations-improved

- Big Ideas: Ending the HIV Epidemic: Policy Action Can Increase Community Support for HIV Cluster Detection - available at https://oneill.law.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Policy-Can-Increase-Community-Support-For-HIV-Cluster-Detection.pdf

- Network for Public Health Law - available at https://www.networkforphl.org/news-insights/data-sharing-agreements

- Addressing Ethical Challenges in US-Based HIV Phylogenetic Research - available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7661760

- Division of HIV Prevention Printable Outreach Materials

- Oster AM, Lyss SB, McClung RP, et al. HIV Cluster and Outbreak Detection and Response: The Science and Experience. Am J Prev Med. Nov 2021;61(5 Suppl 1):S130 S142. Available at https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(21)00363-9/fulltext

- Oster AM, France AM, Panneer N, et al. Identifying Clusters of Recent and Rapid HIV Transmission Through Analysis of Molecular Surveillance Data. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. Dec 15 2018;79(5):543-550. Available at https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001856

- France AM, Panneer N, Ocfemia MCB, et al. Rapidly growing HIV transmission clusters in the United States, 2013–2016. presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; March 2018 Boston, MA. Available at https://www.croiconference.org/abstract/rapidly-growing-hiv-transmission-clusters-united-states-2013-2016/

- McClung RP, Atkins AD, Kilkenny M, et al. Response to a Large HIV Outbreak, Cabell County, West Virginia, 2018-2019. Am J Prev Med. Nov 2021;61(5 Suppl 1):S143-S150. Available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2021.05.039

- Dennis AM, Hue S, Billock R, et al. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Phylodynamics to Detect and Characterize Active Transmission Clusters in North Carolina. J Infect Dis. Mar 28 2020;221(8):1321-1330. Available at https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiz176