At a glance

Ever wonder why the number of illnesses in a foodborne outbreak can increase for weeks, even after the contaminated food is off the market? On this page, you will learn how CDC identifies and investigates an outbreak.

What is a reporting lag

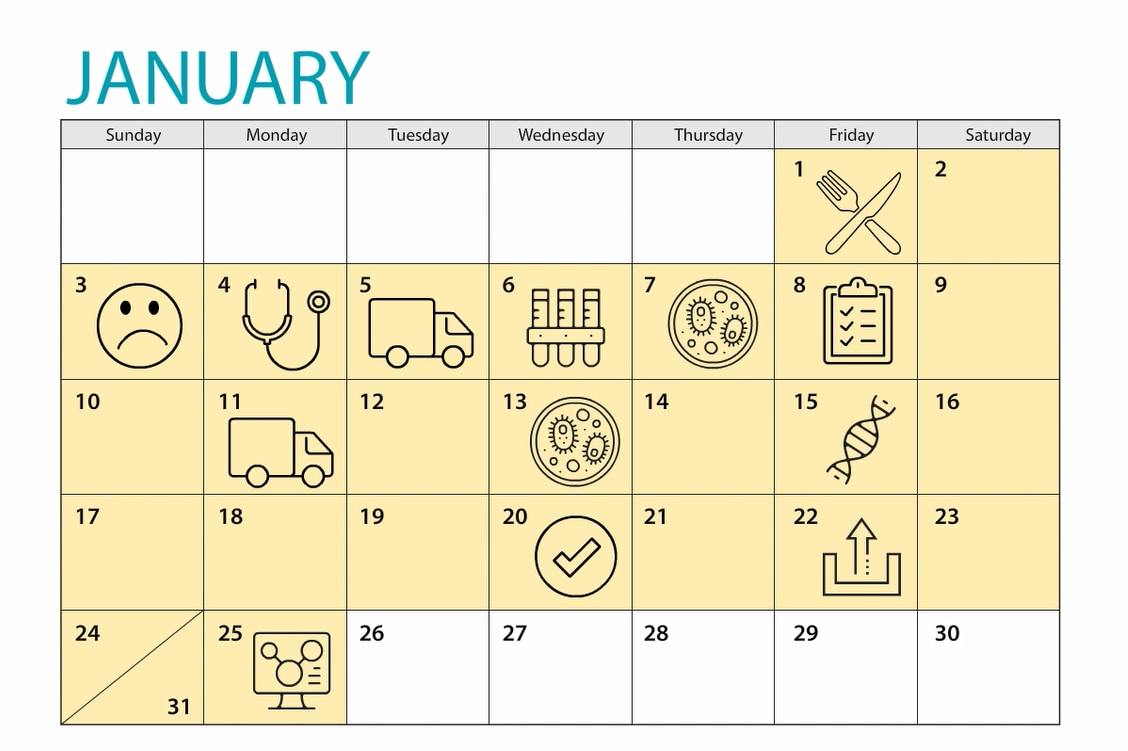

A series of events happen before public health officials can report that a case of illness is linked to an outbreak. Each event takes a certain amount of time. This time is known as the "reporting lag" or "lag window" of an outbreak. It is usually 3–4 weeks. For illnesses caused by some bacteria, such as Listeria, it may be longer. Public health officials work to speed up this process when possible.

The steps below outline what typically happens from the day someone eats a contaminated food to the day their illness is linked to a multistate foodborne outbreak investigated by CDCA.

An example

Day 1: You eat a food containing harmful bacteria

Day 3: You start to feel sick.

Symptoms of food poisoning (such as nausea and diarrhea) could start anywhere from a few hours to a few weeks later, depending on the bacteria you ingested. The following chart describes how long it typically takes for someone to have symptoms after being infected with some of the most common foodborne bacteria.

- Typical Start of Symptoms

- 2-5 days

- 3-4 days

- Within 2 weeks

- 6 hours to 6 days

- 1-2 days

Day 5: You still feel sick with nausea or diarrhea, so you decide to see a healthcare provider.

- To learn which germ is making you sick, the healthcare provider collects a sample of your stool (poop), urine (pee), or blood.

- The provider sends your sample to a clinical laboratory for testing.

Day 6: The clinical laboratory tests your sample.

After receiving your sample, the laboratory takes 1–3 days to run tests, depending on their capacity.

Day 9: Clinical laboratory test results show what germ is causing your illness.

- The clinical laboratory identifies the germ making you sick and reports the test results to your healthcare provider.

- The clinical laboratory should also report test results to the state or local public health department, and they notify CDC.

Days 9–16: The clinical laboratory sends a sample of your bacteria to a public health laboratory.

- The clinical laboratory ships the bacteria found in your sample to a public health laboratory for whole genome sequencing (WGS) analysis.

- Shipping can take up to a week, depending on transportation arrangements in your state and the distance between the two laboratories.

Days 16–21: The public health laboratory performs WGS analysis and other tests on the bacteria.

- The public health laboratory performs tests to determine the bacteria's DNA fingerprint and other characteristics.

- WGS testing and analysis of the results, including whether the bacteria is resistant to any antibiotics, can take 2–10 days depending on the bacteria.

Day 22: The public health laboratory sends WGS results to CDC.

- Within a day of analyzing the WGS results, state public health officials add the DNA fingerprint from the bacteria to PulseNet, a national laboratory network coordinated by CDC. PulseNet connects foodborne illnesses in order to identify outbreaks.

Day 23: CDC determines if your illness is related to other recent illnesses.

- CDC scientists determine whether the bacteria causing your illness is closely related genetically to any other recent WGS results from other people in PulseNet.

- If it is closely related to bacteria causing recent illnesses in other people, CDC may begin an outbreak investigation or add your illness to an ongoing investigation.

Total time: 3–4 weeks

- Most cases of illness, even those caused by common foodborne germs, are not linked to a foodborne outbreak. This can happen for many reasons. A major reason is that most illnesses are not part of an outbreak. Another reason is that germs that cause foodborne illness can also be spread in other ways, such as by water or directly from one person to another. Also, if an illness is diagnosed by a culture-independent diagnostic test, that case may not be linked to an outbreak because these tests do not provide the information needed to link it to an outbreak. In addition, many people do not seek medical care for foodborne illnesses, so their illnesses cannot be diagnosed or reported to public health officials.