Key points

- This fact sheet describes the influence of local government autonomy on emergency medical services and its relation to cardiovascular disease outcomes in medically underserved communities.

- The fact sheet describes the types of state laws analyzed by public health attorneys between January 2021 and January 2022.

- The fact sheet begins to clarify the influence that local government autonomy and property tax laws have on EMS and health outcomes.

Introduction

The Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention created the Home Rule-Emergency Medical Services (HR-EMS) Project to assess the influence of local government autonomy on emergency medical services and its relation to cardiovascular disease outcomes in medically underserved communities.

As part of the project, this state law fact sheet discusses the collection of laws related to local government autonomy to establish and fund local EMS for five U.S. states: Alabama, California, Georgia, Massachusetts, and Ohio.

This fact sheet walks through the types of state laws analyzed by public health attorneys between January 2021 and January 2022.

The laws in this study address local government EMS funding mechanisms related to local property taxes, special districts, mutual aid contracts, issuance of government bonds, and user/service fees.

Bureaucratic requirements, such as voting, public hearing, and public notice requirements, are also analyzed and discussed.

Research that examines the relationship between a community's socioeconomic status and EMS resources is lacking. Further research can help examine EMS funding and its correlation to cardiovascular disease outcomes in disproportionately affected communities.

This fact sheet begins to clarify the influence that local government autonomy and property tax laws have on EMS and health outcomes.

The policy surveillance information presented here may help policy makers, public health practitioners, researchers, and others understand existing structures, facilitators, and challenges that local governments face in providing and funding life-saving emergency medical services. This information can guide improvements and advance health equity.

Snapshot of the laws discussed in this fact sheet

Below are snapshots of the laws discussed in this fact sheet and outlined in more detail in Table 1: Summary of Laws Pertaining to Local Government Autonomy and Local EMS Funding Mechanisms, in Effect as of January 31, 2022.

EMS background

In the United States, emergency medical services are not considered essential services.1 They are provided and funded mainly by local governments, which leads to a wide variation in the cost and quality of services.

Nationwide, the cost of ambulance transport for ground ambulance providers varies substantially. Although recent estimates are limited, as of 2012, the median cost per transport was $429, but depending on the geographic area, this cost could be as low as $224 or as high as $2,204 (for both Medicare and non-Medicare transports).2

Communities with lower average household incomes have a higher incidence of severe, life-threatening illnesses and rely more heavily on EMS (prehospital) care.3 However, one recent nationwide study found that areas with higher median household incomes have shorter EMS response times and a higher percentage of White residents.3

These differences in quality may also be due to system structure.3 In addition to variations in cost, there are also differences in the level of service to rural areas across the United States. Rural counties have a higher percentage of elderly residents and residents with limitations in activities due to chronic conditions, as well as a lower median income than their urban counterparts. These factors make them among the groups that most need hospital services.4 A 2018 study found that the 43% of rural hospitals that closed between 2005 and 2017 were more than 15 miles from the next closest hospital, resulting in substantially longer transport times.5

Finally, female patients and patients in minority populations are disproportionately affected by delays and other shortcomings in emergency medical care.6 For example, a nationwide EMS study reported that a lower percentage of women with chest pain received recommended treatments during emergency care.6

In the United States, EMS care is funded mainly at the local level. Some states have adopted a more centralized EMS infrastructure, while others allow local jurisdictions to retain greater authority to develop, fund, and implement their EMS systems. These differences among states may be explained in part by the extent to which states constitutionally or legislatively grant local jurisdictions the power to enact their own laws to address issues of local concern, a concept known as local autonomy.7

Such powers allow counties and cities to adopt their own public health laws around the provision and funding of emergency medical care.

Common sources of local government revenue include taxes (primarily property and sales taxes), user fees/fines, and bonds. Special districts are also frequently used to help fund these services.

Data collection and methods

Between January 2021 and January 2022, four public health attorneys and three legal interns (collectively referred to as the project team) collected and analyzed state statutes in effect as of January 31, 2022. They gathered relevant laws in Alabama, California, Georgia, Massachusetts, and Ohio from Westlaw Edge (Thomson Reuters in Eagan, Minnesota) and official state legislation websites.

States were selected based on:

- Geographic diversity (at least one state from each of the following Census regions: Northeast, South, Midwest, West).

- Diversity in urban/rural breakdown in each state (based on the 2018 CityLab's Congressional Density Index).8

- Availability of public information about state and local EMS funding.

- Amount of local government revenue generated from property taxes (based on 2017 U.S. Census Bureau revenue data and the state property tax database by Lincoln Institute of Land Policy).9

Before collecting data and coding laws, the project team conducted a literature review and consulted experts in the legal field to help them develop coding protocols. The protocols outline exclusion and inclusion criteria, coding instructions, and coding questions.

For each state, two project team members independently collected and coded the laws using the coding protocols. The two team members subsequently met to discuss and reconcile discrepancies in codes and analyses of state law.

The project team coded state laws related to local autonomy and funding of local EMS. This study does not include analysis of:

- Case law (law based on judicial decisions).

- Special districts that do not pertain to EMS or fire services.

- Laws pertaining to property, such as laws governing eminent domain, blighted property, or tax penalties.

State laws

Local governments' authority to regulate local EMS agencies

Laws from each state were analyzed to assess the level of authorized local government autonomy to establish and fund local EMS agencies. Four of the five states grant statewide local government autonomy (i.e., all local governments in the state can enact ordinances to regulate local EMS).

Table 2a lists laws related to statewide local government autonomy in effect as of January 31, 2022. Although Alabama does not allow statewide local government autonomy, selected local governments are granted autonomy through constitutional amendments (e.g., ALA. CONST. amend. 783, § 5.01 [West, Westlaw through 2021 amendments]).

Taxes and government bonds as funding mechanisms for local EMS

In all five states, special taxes are allowed and require an election in the community in order to be imposed. Special taxes are those levied when the county or special district's board of directors finds that the current revenue is insufficient to cover the expenses of the local EMS agency.

Bonds are another method that local governments may use to supply the needs of local EMS agencies. The ability to incur debt for local EMS purposes is authorized throughout the five states. The type of bonds analyzed varied by state (see Table 1 for type of local bonds analyzed; see Table 2b for a compiled list of laws).

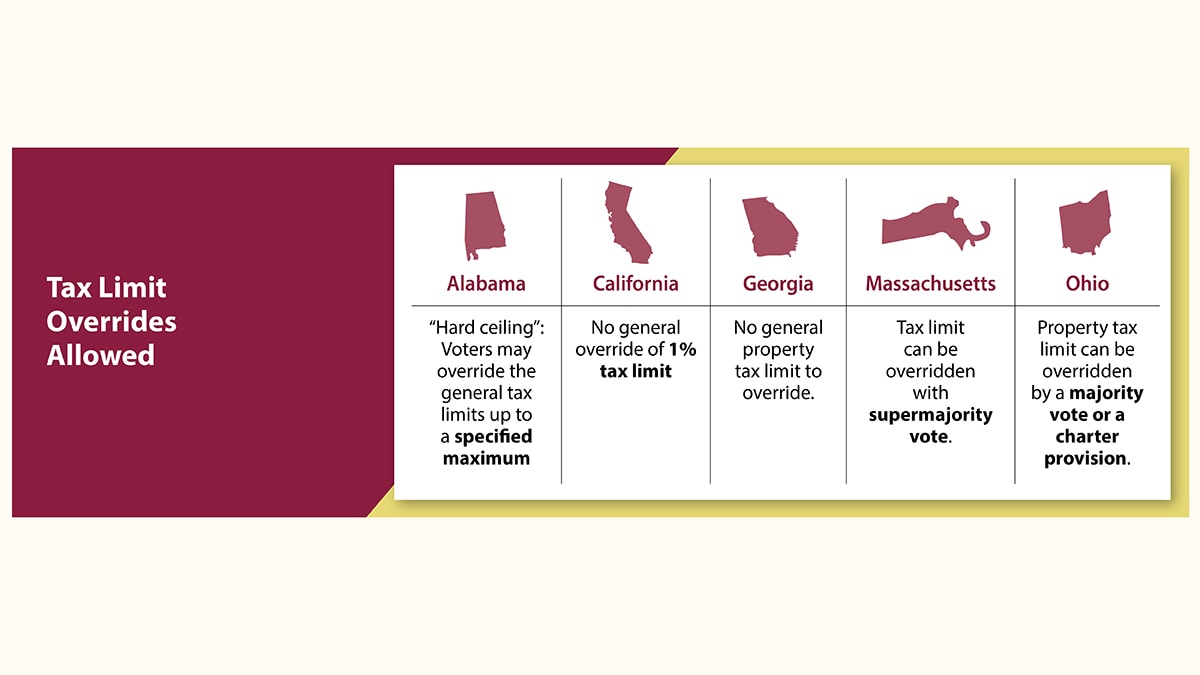

State government restrictions on local tax levies and government bonds

Local government tax levies and bonds may be subject to limitations. Restrictions vary by statute, and the local government must adhere to these restrictions before it can establish local ordinances. Table 1 lists authorized purposes of tax levies and bonds that relate to EMS. It also lists other restrictions, such as frequency of tax assessment, maximum tax rate, maximum interest rate, and maximum term (see Tables 2a and 2b for the specific local tax and government bond restrictions for each statutory citation listed).

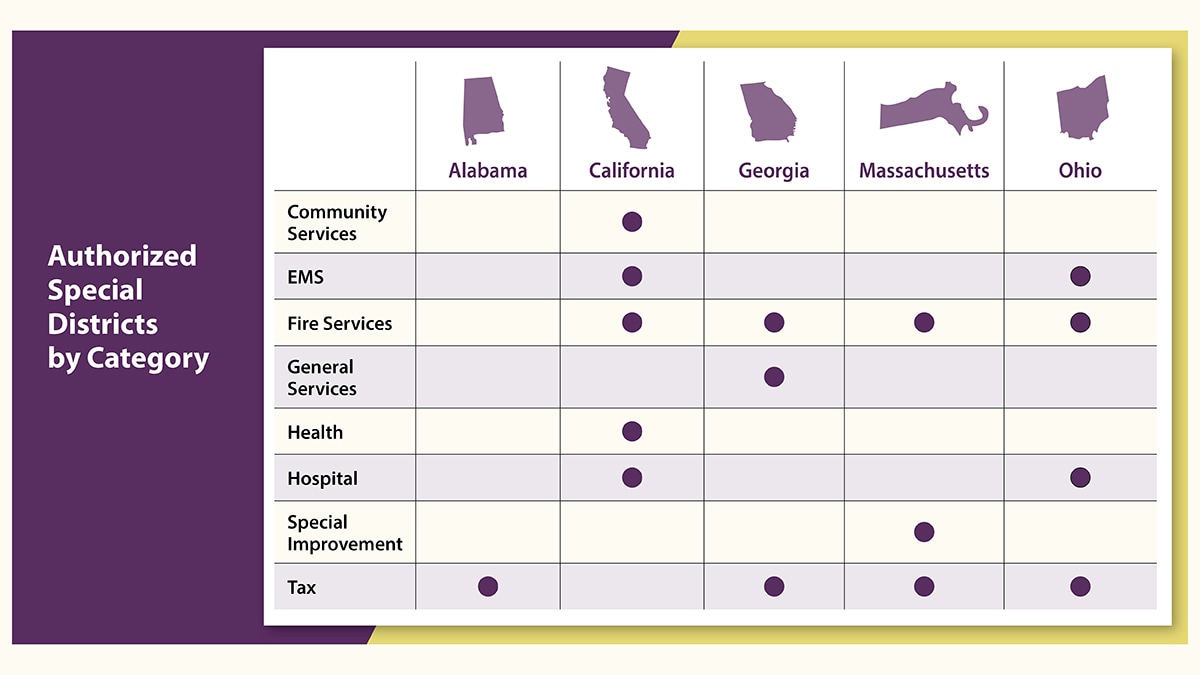

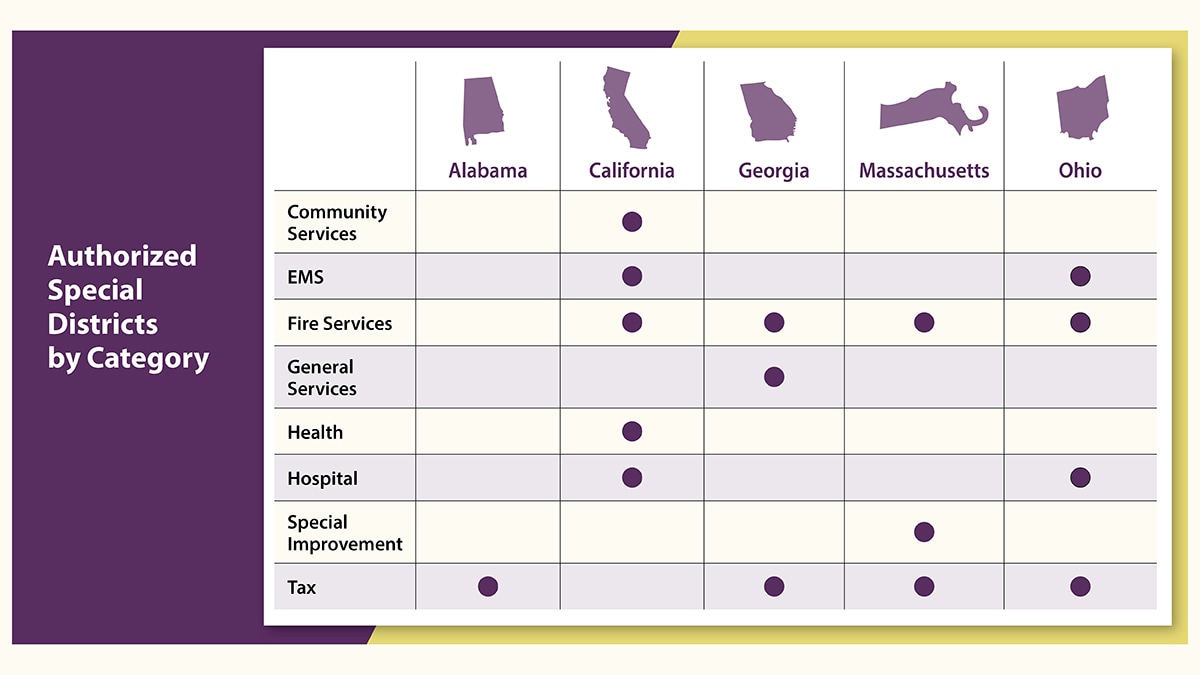

Special districts authorized to provide and fund local EMS

Special districts are created by local governments to provide and/or fund public services for their communities. Taxes imposed by special districts allow local governments to collect additional revenue that is typically not subject to state tax limitations.

Although most special district laws are limited in scope, some are drafted more broadly to encompass a variety of municipal services needed in a community (see Table 2a for all special district types permitted to establish and/or fund local EMS and for special districts' laws analyzed).

Mutual aid contracts to provide local EMS

All five states authorize local governments/special districts to enter into mutual aid contracts with other local governments/special districts to provide or receive EMS. Under these contracts, local governments can elect to charge the citizens of the recipient community a reasonable fee for EMS care rendered (with the reasonableness of the fee to be agreed upon by the contracting counties; see Table 2b for mutual aid laws analyzed).

Fees as revenue for local EMS purposes

Local governments/special districts are allowed to charge a fee for services provided to their communities (see Table 1 for the types of fees permitted in each state). Fees are then used as revenue to maintain equipment, construct buildings, pay wages, and/or supply anything necessary to fulfill the purpose of the district or service provided. Fees can also be used as revenue to satisfy bond payments. State enacted procedural requirements for local laws. Before establishing local taxes, bonds, special districts, fees, and mutual aid agreements, a state government may require a local government to complete a bureaucratic process or other procedure. Such requirements may include:

- Public advertisements/notices.

- Public hearings.

- Voter approval of the local government board members or citizens.

- Adoption of a county charter.

See Tables 2a and 2b for the procedural requirements for each statutory citation listed.

Implications and conclusions

Understanding local governments' legal authority to self-govern and establish local EMS agencies will aid efforts to improve health disparities in access to pre-hospital care among underserved communities across the United States.

In each state analyzed, communities' property value influenced the availability of funds for local EMS. Since the majority of EMS funds come from property tax, this raises health equity concerns (e.g., access to quality care) for lower-income communities. There is a lack of research into the relationship between a community's socioeconomic status and its EMS resources. Further research can help examine EMS funding and its correlation to cardiovascular disease outcomes in disproportionately affected communities.

Based on the project team's knowledge after extensive research, this is the first study that captures local governments' ability to provide and fund emergency medical services through local autonomy laws, tax laws, and special district laws. However, this study is subject to limitations.

- First, laws analyzed in this study do not represent the totality of state laws that may address local government autonomy and the enactment of local laws permitted by state governments.

- Second, this state law fact sheet examines only five states, so it presents a limited analysis of the relevant laws and policies across the nation.

Nonetheless, the policy surveillance information presented may help policy makers, public health practitioners, researchers, and others to understand structures, facilitators and challenges facing local governments in their ability to provide and fund life-saving EMS services. This information may help guide improvements and advance health equity.

The provision and funding of emergency medical services is complex. For a deeper analysis of the organization and funding of EMS, the HR-EMS project will release two additional fact sheets. The first will describe local government autonomy and EMS funding, organization, management, while the second will explore disparities in EMS service and CVD outcomes. In addition to national data, both fact sheets will also describe a case study of five local EMS agencies in California.

Acknowledgements

The four public health attorneys are contractors of ASRT, Inc., and work with the Applied Research and Translation team in the Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A special thank you to the CDC's Public Health Law Program legal interns, Alex Sedlak, Shreya Santhanam, and Marie Carp, for assisting in the research and outline of this state law fact sheet.

Disclaimer

This fact sheet presents a summary of local autonomy and EMS-related state laws in effect as of January 31, 2022, and is not intended to promote any particular legislative, regulatory, or other action. It is not intended as a substitute for professional, legal, or other advice. Always seek the advice of an attorney or other qualified professional with any questions you may have about a legal matter.

- Johnson C, Curti D. EMS services across state lines. Texas Tech Admin Law J. 2015;16:333–356.

- United States Government Accountability Office. Ambulance Providers: Costs and Medicare Margins Varied Widely; Transports of Beneficiaries Have Increased. 2012. Report to Congressional Committees GAO-13-6. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-13-6

- Hsia RY, Huang D, Mann NC, et al. A U.S. national study of the association between income and ambulance response time in cardiac arrest. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(7):e185202.

- Covitz JA, Richter A, MacKinnon DJ. 911 and the area code from which you call: how to improve the disparity in California's emergency medical services. J Emerg Manag. 2020;18(3):247–260.

- United States Government Accountability Office. Rural Hospital Closures: Number and Characteristics of Affected Hospitals and Contributing Factors. 2018. Report to Congressional Requesters GAO-18-634. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-18-634.pdf [PDF – 857 KB]

- Lewis JF, Zeger SL, Li X, et al. Sex differences in the quality of EMS care nationwide for chest pain and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Women's Health Issues. 2019;29(2):116–124.

- Wolman H, McManmon R, Bell M, Brunori D, et al. Comparing local government autonomy across states. Annual Conference on Taxation and Minutes of the Annual Meeting of the National Tax Association. 2008;101:377–383.

- CityLab. CityLab's Congressional Density Index [Database]. The Atlantic. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://github.com/theatlantic/citylab-data/blob/master/citylab-congress/methodology.md

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2017 State & Local Government Finance Tables [Database]. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/econ/gov-finances/summary-tables.html