At a glance

This page includes recommendations for health care providers that address provision and use of combined hormonal contraceptives. This information comes from the 2024 U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use (U.S. SPR).

Overview

Combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) contain both estrogen and a progestin and include combined oral contraceptives (COCs) (various formulations), combined transdermal patches, and combined vaginal rings. Approximately seven out of 100 CHC users become pregnant in the first year with typical use.[28] These methods are reversible and can be used by patients of all ages. Combined hormonal contraceptives are generally used for 21–24 consecutive days, followed by 4–7 hormone-free days (either no use or placebo pills). These methods are sometimes used for an extended period with infrequent or no hormone-free days. CHCs do not protect against sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and patients using CHCs should be counseled that consistent and correct use of external (male) latex condoms reduces the risk for STIs, including HIV infection.[31] Use of internal (female) condoms can provide protection from STIs, including HIV infection, although data are limited.[31] Patients also should be counseled that pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), when taken as prescribed, is highly effective for preventing HIV infection.[32]

Initiation of CHCs

Timing

- CHCs may be initiated at any time if it is reasonably certain that the patient is not pregnant (Box 3).

Need for Back-Up Contraception

- If CHCs are started within the first 5 days since menstrual bleeding started, no additional contraceptive protection is needed.

- If CHCs are started >5 days since menstrual bleeding started, the patient needs to abstain from sexual intercourse or use barrier methods (e.g., condoms) for the next 7 days.

Special Considerations

Amenorrhea (Not Postpartum)

- Timing: CHCs may be started at any time if it is reasonably certain that the patient is not pregnant (Box 3).

- Need for back-up contraception: The patient needs to abstain from sexual intercourse or use barrier methods (e.g., condoms) for the next 7 days.

Postpartum (Breastfeeding)

- Timing: CHCs may be started when the patient is medically eligible to use the method[1] and if it is reasonably certain that they are not pregnant (Box 3).

- Postpartum patients who are breastfeeding should not use CHCs <21 days postpartum (U.S. MEC 4).[1] Postpartum patients who are breastfeeding generally should not use CHCs during 21 to <30 days postpartum (U.S. MEC 3).[1] Postpartum breastfeeding patients with other risk factors for venous thromboembolism generally should not use CHCs 30–42 days postpartum (U.S. MEC 3).[1] However, postpartum breastfeeding patients without other risk factors for venous thromboembolism generally can use CHCs 30–42 days postpartum (U.S. MEC 2),[1] and all breastfeeding patients generally can use CHCs >42 days postpartum (U.S. MEC 2).[1]

- Need for back-up contraception: If the patient is <6 months postpartum, amenorrheic, and fully or nearly fully breastfeeding (exclusively breastfeeding or the vast majority [≥85%] of feeds are breastfeeds),[44] no additional contraceptive protection is needed. Otherwise, a patient who is ≥21 days postpartum and whose menstrual cycle has not returned needs to abstain from sexual intercourse or use barrier methods (e.g., condoms) for the next 7 days. If the patient's menstrual cycle has returned and it has been >5 days since menstrual bleeding started, the patient needs to abstain from sexual intercourse or use barrier methods (e.g., condoms) for the next 7 days.

Postpartum (Nonbreastfeeding)

- Timing: CHCs may be started when the patient is medically eligible to use the method[1] and if it is reasonably certain that the patient is not pregnant (Box 3).

- Postpartum patients should not use CHCs <21 days postpartum (U.S. MEC 4).[1] Postpartum patients with other risk factors for venous thromboembolism generally should not use CHCs 21–42 days postpartum (U.S. MEC 3).[1] However, postpartum patients without other risk factors for venous thromboembolism generally can use CHCs 21–42 days postpartum (U.S. MEC 2),[1] and all postpartum patients can use CHCs >42 days postpartum (U.S. MEC 1).[1]

- Need for back-up contraception: If the patient is <21 days postpartum, no additional contraceptive protection is needed. A patient who is ≥21 days postpartum and whose menstrual cycle has not returned needs to abstain from sexual intercourse or use barrier methods (e.g., condoms) for the next 7 days. If the patient's menstrual cycle has returned and it has been >5 days since menstrual bleeding started, the patient needs to abstain from sexual intercourse or use barrier methods (e.g., condoms) for the next 7 days.

Postabortion (Spontaneous or Induced)

- Timing: CHCs may be started at any time postabortion, including immediately after abortion completion, if it is reasonably certain that the patient is not pregnant (Box 3), or at the time of medication abortion initiation (U.S. MEC 1).[1]

- Need for back-up contraception: The patient needs to abstain from sexual intercourse or use barrier methods (e.g., condoms) for the next 7 days unless CHCs are started at the time of an abortion.

Switching from Another Contraceptive Method

- Timing: CHCs may be started immediately if it is reasonably certain that the patient is not pregnant (Box 3). Waiting for the patient's next menstrual cycle is unnecessary.

- Need for back-up contraception: If it has been >5 days since menstrual bleeding started, the patient needs to abstain from sexual intercourse or use barrier methods (e.g., condoms) for the next 7 days.

- Switching from an intrauterine device (IUD): In addition to the need for back-up contraception when starting CHCs, there might be additional concerns when switching from an IUD. If the patient has had sexual intercourse since the start of their current menstrual cycle and it has been >5 days since menstrual bleeding started, theoretically, residual sperm might be in the genital tract, which could lead to fertilization if ovulation occurs. A health care provider may consider any of the following options to address the potential for residual sperm:

- Advise the patient to retain the IUD for at least 7 days after CHCs are initiated and return for IUD removal.

- Advise the patient to abstain from sexual intercourse or use barrier methods (e.g., condoms) for 7 days before removing the IUD and switching to the new method. If it has been >5 days since menstrual bleeding started, the patient needs to abstain from sexual intercourse or use barrier methods (e.g., condoms) for the next 7 days.

- If the patient cannot return for IUD removal and has not abstained from sexual intercourse or used barrier methods (e.g., condoms) for 7 days, advise the patient to use emergency contraceptive pills (ECPs) at the time of IUD removal. CHCs may be started immediately after use of ECPs (with the exception of ulipristal acetate [UPA]). CHCs may be started no sooner than 5 days after use of UPA. If it has been >5 days since menstrual bleeding started, the patient needs to abstain from sexual intercourse or use barrier methods (e.g., condoms) for the next 7 days.

- Advise the patient to retain the IUD for at least 7 days after CHCs are initiated and return for IUD removal.

Comments and Evidence Summary

In situations in which the health care provider is uncertain whether the patient might be pregnant, the benefits of starting CHCs likely exceed any risk; therefore, starting CHCs should be considered at any time, with a follow-up pregnancy test in 2–4 weeks. If a patient needs to use additional contraceptive protection when switching to CHCs from another contraceptive method, consider continuing their previous method for 7 days after starting CHCs. (As appropriate, see recommendations for Emergency Contraception.)

A systematic review of 18 studies examined the effects of starting CHCs on different days of the menstrual cycle.[261] Overall, the evidence suggested that pregnancy rates did not differ by the timing of CHC initiation[220],[262–264] (Level of evidence: I to II-3, fair, indirect). The more follicular activity that occurred before starting COCs, the more likely ovulation was to occur; however, no ovulations occurred when COCs were started at a follicle diameter of 10 mm (mean cycle day 7.6) or when the ring was started at 13 mm (median cycle day 11)[265–274] (Level of evidence: I to II-3, fair, indirect). Bleeding patterns and other side effects did not vary with the timing of CHC initiation[263],[264],[275–279] (Level of evidence: I to II-2, good to poor, direct). Although continuation rates of CHCs were initially improved by the "quick start" approach (i.e., starting on the day of the visit), the advantage disappeared over time[262],[263],[275–280] (Level of evidence: I to II-2, good to poor, direct).

Examinations and tests needed before initiation of CHCs

Among healthy patients, few examinations or tests are needed before initiation of CHCs (Table 4). Blood pressure should be measured before initiation of combined hormonal contraceptives. Baseline weight and body mass index (BMI) measurements might be useful for addressing any concerns about changes in weight over time. Patients with known medical problems or other special conditions might need additional examinations or tests before being determined to be appropriate candidates for a particular method of contraception. U.S. MEC might be useful in such circumstances.[1]

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; STI = sexually transmitted infection; U.S. MEC = U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use.

* Class A: Essential and mandatory in all circumstances for safe and effective use of the contraceptive method.

Class B: Contributes substantially to safe and effective use, but implementation may be considered within the public health context, service context, or both; the risk of not performing an examination or test should be balanced against the benefits of making the contraceptive method available.

Class C: Does not contribute substantially to safe and effective use of the contraceptive method. (Source: World Health Organization. Selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2004.)

† In instances in which blood pressure cannot be measured by a provider, blood pressure measured in other settings can be reported by the patient to their provider.

§ Weight (BMI) measurement is not needed to determine medical eligibility for any methods of contraception because all methods can be used (U.S. MEC 1) or generally can be used (U.S. MEC 2) among patients with obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2). However, measuring weight and calculating BMI at baseline might be helpful for discussing concerns about any changes in weight and whether changes might be related to use of the contraceptive method.

Blood pressure: Patients who have more severe hypertension (systolic pressure of ≥160 mm Hg or diastolic pressure of ≥100 mm Hg) or vascular disease should not use CHCs (U.S. MEC 4), and patients who have less severe hypertension (systolic pressure of 140–159 mm Hg or diastolic pressure of 90–99 mm Hg) or adequately controlled hypertension generally should not use CHCs (U.S. MEC 3).[1] Therefore, blood pressure should be evaluated before initiating CHCs. In instances in which blood pressure cannot be measured by a provider, blood pressure measured in other settings can be reported by the patient to their provider. Evidence suggests that cardiovascular outcomes are worse among women who did not have their blood pressure measured before initiating COCs. A systematic review identified six articles from three studies that reported cardiovascular outcomes among women who had blood pressure measurements and women who did not have blood pressure measurements before initiating COCs.[221] Three case-control studies demonstrated that women who did not have blood pressure measurements before initiating COCs had a higher risk for acute myocardial infarction than women who did have blood pressure measurements.[281–283] Two case-control studies demonstrated that women who did not have blood pressure measurements before initiating COCs had a higher risk for ischemic stroke than women who did have blood pressure measurements.[284],[285] One case-control study reported no difference in the risk for hemorrhagic stroke among women who initiated COCs regardless of whether their blood pressure was measured.[286] Studies that examined hormonal contraceptive methods other than COCs were not identified (Level of evidence: II-2, fair, direct).

Weight (BMI): Patients with obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) generally can use CHCs (U.S. MEC 2);[1] therefore, screening for obesity is not necessary for the safe initiation of CHCs. However, measuring weight and calculating BMI at baseline might be helpful for discussing concerns about any changes in weight and whether changes might be related to use of the contraceptive method.

Bimanual examination and cervical inspection: Pelvic examination is not necessary before initiation of CHCs because it does not facilitate detection of conditions for which hormonal contraceptives would be unsafe. Although patients with certain conditions or characteristics should not use (U.S. MEC 4) or generally should not use (U.S. MEC 3) CHCs,[1] none of these conditions are likely to be detected by pelvic examination.[172] A systematic review identified two case-control studies that compared delayed and immediate pelvic examination before initiation of hormonal contraceptives, specifically oral contraceptives or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA).[23] No differences in risk factors for cervical neoplasia, incidence of STIs, incidence of abnormal Papanicolaou smears, or incidence of abnormal wet mounts were found (Level of evidence: II-2 fair, direct).

Glucose: Although patients with complicated diabetes should not use (U.S. MEC 4) or generally should not use (U.S. MEC 3) CHCs, depending on the severity of the condition,[1] screening for diabetes before initiation of hormonal contraceptives is not necessary because of the low prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes and the high likelihood that patients with complicated diabetes already would have had the condition diagnosed. A systematic review did not identify any evidence regarding outcomes among women who were screened versus not screened with glucose measurement before initiation of hormonal contraceptives.[24] The prevalence of diabetes among women of reproductive age is low. During 2011–2016 among women aged 20–44 years in the United States, the prevalence of diabetes was 4.5% and the prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes was 1.3%.[222] Although hormonal contraceptives can have certain adverse effects on glucose metabolism in healthy women and women with diabetes, the overall clinical effect is minimal.[223–229]

Lipids: Screening for dyslipidemias is not necessary for the safe initiation of CHCs because of the low likelihood of clinically significant changes with use of hormonal contraceptives. A systematic review did not identify any evidence regarding outcomes among women who were screened versus not screened with lipid measurement before initiation of hormonal contraceptives.[24] During 2015–2016 among women aged 20–39 years in the United States, 6.7% had high cholesterol, defined as total serum cholesterol >240 mg/dL.[111] A systematic review identified few studies, all of poor quality, that suggest that women with known dyslipidemias using CHCs might be at increased risk for myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident, or venous thromboembolism compared with women without dyslipidemias; no studies were identified that examined risk for pancreatitis among women with known dyslipidemias using CHCs.[115] Studies have reported mixed results regarding the effects of hormonal contraceptives on lipid levels among both healthy women and women with baseline lipid abnormalities, and the clinical significance of these changes is unclear.[112–115]

Liver enzymes: Although patients with certain liver diseases should not use (U.S. MEC 4) or generally should not use (U.S. MEC 3) CHCs,[1] screening for liver disease before initiation of CHCs is not necessary because of the low prevalence of these conditions and the high likelihood that patients with liver disease already would have had the condition diagnosed. A systematic review did not identify any evidence regarding outcomes among women who were screened versus not screened with liver enzyme tests before initiation of hormonal contraceptives.[24] During 2012, among U.S. women, the percentage with liver disease (not further specified) was 1.3%.[116] During 2013, the incidence of acute hepatitis A, B, or C was ≤1 per 100,000 U.S. population.[117] During 2002–2011, the incidence of liver cancer among U.S. women was approximately 3.7 per 100,000 population.[118]

Thrombophilia: Patients with thrombophilia should not use CHCs (U.S. MEC 4).[1] However, studies have demonstrated that routine thrombophilia screening in the general population before contraceptive initiation is not cost-effective because of the rarity of the conditions and high cost of screening.[230–234]

Clinical breast examination: Although patients with current breast cancer should not use CHCs (U.S. MEC 4),[1] screening asymptomatic patients with a clinical breast examination before initiating CHCs is not necessary because of the low prevalence of breast cancer among women of reproductive age. A systematic review did not identify any evidence regarding outcomes among women who were screened versus not screened with a breast examination before initiation of hormonal contraceptives.[23] The incidence of breast cancer among women of reproductive age in the United States is low. During 2020, the incidence of breast cancer among women aged <50 years was approximately 45.9 per 100,000 women.[119]

Other screening: Patients with iron-deficiency anemia, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, cervical cancer, HIV infection, or other STIs can use (U.S. MEC 1) or generally can use (U.S. MEC 2) CHCs.[1] Therefore, screening for these conditions is not necessary for the safe initiation of combined hormonal contraceptives.

Number of pill packs that should be provided at initial and return visits

- At the initial and return visits, provide or prescribe up to a 1-year supply of COCs (e.g., 13 28-day pill packs), depending on the patient's preferences and anticipated use.

- A patient should be able to obtain COCs easily in the amount and at the time they need them.

Comments and Evidence Summary

The more pill packs provided up to 13 cycles, the higher the continuation rates. Restricting the number of pill packs distributed or prescribed can be a barrier for patients who want to continue COC use and might increase risk for pregnancy.

A systematic review of the evidence suggested that providing a greater number of pill packs was associated with increased continuation.[20] Studies that compared provision of one versus 12 packs, one versus 12 or 13 packs, or three versus seven packs found increased continuation of pill use among women provided with more pill packs.[287–289] However, one study found no difference in continuation when patients were provided one and then three packs versus four packs all at once.[290] In addition to continuation, a greater number of pill packs provided was associated with fewer pregnancy tests, fewer pregnancies, and lower cost per client. However, a greater number of pill packs (i.e., 13 packs versus three packs) also was associated with increased pill wastage in one study[288] (Level of evidence: I to II-2, fair, direct).

Routine follow-up after CHC initiation

These recommendations address when routine follow-up is recommended for safe and effective continued use of contraception for healthy patients. The recommendations refer to general situations and might vary for different users and different situations. Specific populations who might benefit from more frequent follow-up visits include adolescents, those with certain medical conditions or characteristics, and those with multiple medical conditions.

- Advise the patient that they may contact their provider at any time to discuss side effects or other problems or if they want to change the method being used. No routine follow-up visit is required.

- At other routine visits, health care providers seeing CHC users should do the following:

- Assess the patient’s satisfaction with their contraceptive method and whether they have any concerns about method use.

- Assess any changes in health status, including medications, that would change the appropriateness of CHCs for safe and effective continued use on the basis of U.S. MEC (e.g., category 3 and 4 conditions and characteristics).[1]

- Assess blood pressure.

- Consider assessing weight changes and discussing concerns about any changes in weight and whether changes might be related to use of the contraceptive method.

- Assess the patient’s satisfaction with their contraceptive method and whether they have any concerns about method use.

Comments and Evidence Summary

No evidence exists regarding whether a routine follow-up visit after initiating CHCs improves correct or continued use. Monitoring blood pressure is important for CHC users. Health care providers might consider recommending patients obtain blood pressure measurements in other settings, including self-measured blood pressure.

A systematic review identified five studies that examined the incidence of hypertension among women who began using a COC versus those who started a nonhormonal method of contraception or a placebo.[21] Few women developed hypertension after initiating COCs, and studies examining increases in blood pressure after COC initiation found mixed results. No studies were identified that examined changes in blood pressure among patch or vaginal ring users (Level of evidence: I, fair, to II-2, fair, indirect).

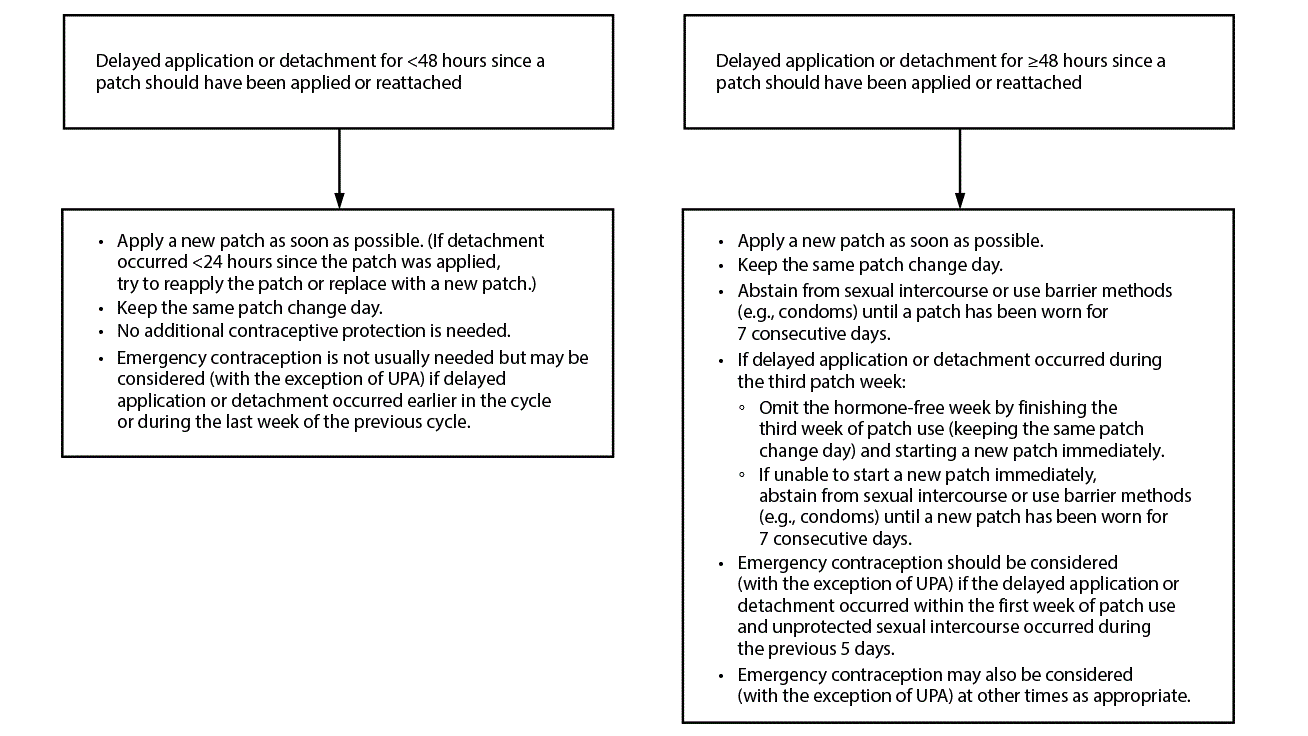

Late or missed doses and side effects from CHC use

For the following recommendations, a dose is considered late when <24 hours have elapsed since the dose should have been taken. A dose is considered missed if ≥24 hours have elapsed since the dose should have been taken. For example, if a COC pill was supposed to have been taken on Monday at 9:00 a.m. and is taken at 11:00 a.m., the pill is late; however, by Tuesday morning at 11:00 a.m., Monday's 9:00 a.m. pill has been missed and Tuesday's 9:00 a.m. pill is late. For COCs, the recommendations only apply to late or missed hormonally active pills and not to placebo pills. Recommendations are provided for late or missed pills (Figure 1), the patch (Figure 2), and the ring (Figure 3).

Comments and Evidence Summary

Inconsistent or incorrect use of CHCs is a major cause of CHC failure. Extending the hormone-free interval (e.g., missing hormonally active pills either directly before or after the placebo or pill-free interval) is considered to be a particularly risky time to miss CHCs. Seven days of continuous CHC use is deemed necessary to reliably prevent ovulation. The recommendations reflect a balance between the complexity of the evidence and determination of a simple and feasible recommendation. For patients who frequently miss COCs or experience other usage errors with combined transdermal patches or combined vaginal rings, explore patient goals, consider offering counseling on alternative contraceptive methods, and initiate another method if it is desired.

A systematic review identified 36 studies that examined measures of contraceptive effectiveness of CHCs during cycles with extended hormone-free intervals, shortened hormone-free intervals, or deliberate nonadherence on days not adjacent to the hormone-free interval.[291] Most of the studies examined COCs,[274],[292–319] two examined the combined transdermal patch,[313],[320] and six examined the combined vaginal ring (etonogestrel/ethinyl estradiol [EE]).[270],[321–325] No direct evidence on the effect of missed pills on the risk for pregnancy was found. Studies of women deliberately extending the hormone-free interval up to 14 days found wide variability in the amount of follicular development and occurrence of ovulation;[295],[298],[300],[301],[303],[304],[306–309] in general, the risk for ovulation was low, and among women who did ovulate, cycles were usually abnormal. In studies of women who deliberately missed pills on various days during the cycle not adjacent to the hormone-free interval, ovulation occurred infrequently. [293],[299–301],[309], [310],[312],[313] Studies comparing 7-day hormone-free intervals with shorter hormone-free intervals found lower rates of pregnancy[292],[296],[305],[311] and significantly greater suppression of ovulation[294],[304],[315–317],[319] among women with shorter intervals in all but one study,[314] which found no difference. Two studies that compared 30-µg EE pills with 20-µg EE pills demonstrated more follicular activity when 20-µg EE pills were missed.[295],[298] In studies examining the combined vaginal ring, three studies found that nondeliberate extension of the hormone-free interval for 24 to <48 hours from the scheduled period did not increase the risk for pregnancy;[321],[322],[324] one study found that ring placement after a deliberately extended hormone-free interval that allowed a 13-mm follicle to develop interrupted ovarian function and further follicular growth;[270] and one study found that inhibition of ovulation was maintained after deliberately forgetting to remove the ring for up to 2 weeks after normal ring use.[325] In studies examining the combined transdermal patch, one study found that missing 1–3 consecutive days before patch replacement (either wearing one patch 3 days longer before replacement or going 3 days without a patch before replacing the next patch) on days not adjacent to the patch-free interval resulted in little follicular activity and low risk for ovulation,[313] and one pharmacokinetic study found that serum levels of EE and progestin norelgestromin remained within reference ranges after extending patch wear for 3 days.[320] No studies were found on extending the patch-free interval. In studies that provide indirect evidence on the effects of missed combined hormonal contraception on surrogate measures of pregnancy, how differences in surrogate measures correspond to pregnancy risk is unclear (Level of evidence: I, good, indirect to II-3, poor, direct).

Figure 1. Recommended actions after late or missed combined oral contraceptives

Abbreviation: UPA = ulipristal acetate.

Figure 2. Recommended actions after delayed application or detachment* with combined hormonal patch

Abbreviation: UPA = ulipristal acetate.

* If detachment takes place but the patient is unsure when the detachment occurred, consider the patch to have been detached for ≥48 hours since a patch should have been applied or reattached.

Figure 3. Recommended actions after delayed placement or replacement* with combined vaginal ring (etonogestrel/ethinyl estradiol)†

Abbreviation: UPA = ulipristal acetate.

* If removal takes place but the patient is unsure when the ring was removed, consider the ring to have been removed for ≥48 hours since a ring should have been placed or replaced.

† These recommendations are based on evidence for the etonogestrel/ethinyl estradiol combined vaginal ring. For dosing errors with the segesterone acetate/ethinyl estradiol vaginal ring, please see the package label.

Vomiting or severe diarrhea while using COCs

Certain steps should be taken by patients who experience vomiting or severe diarrhea while using COCs (Figure 4).

Comments and Evidence Summary

Theoretically, the contraceptive effectiveness of COCs might be decreased because of vomiting or severe diarrhea. Because of the lack of evidence that addresses vomiting or severe diarrhea while using COCs, these recommendations are based on the recommendations for missed COCs. No evidence was found on the effects of vomiting or diarrhea on measures of contraceptive effectiveness including pregnancy, follicular development, hormone levels, or cervical mucus quality.

Figure 4. Recommended actions after vomiting or diarrhea while using combined oral contraceptives

Abbreviation: UPA = ulipristal acetate.

Bleeding irregularities with extended or continuous use of CHCs

- Before initiation of CHCs, provide counseling about potential changes in bleeding patterns during extended or continuous CHC use. Extended contraceptive use has been defined as a planned hormone-free interval after more than 28 days of active hormones. Continuous contraceptive use has been defined as uninterrupted use of hormonal contraception without a hormone-free interval.[326]

- Spotting or bleeding is common during the first 3–6 months of extended or continuous CHC use. Spotting or bleeding is generally not harmful but might be bothersome to the patient. Bleeding changes generally decrease with continued CHC use.

- If clinically indicated, consider an underlying health condition, such as inconsistent use, interactions with other medications, cigarette smoking, STIs, pregnancy, thyroid disorders, or new pathologic uterine conditions (e.g., polyps or fibroids). If an underlying health condition is found, treat the condition or refer for care.

- Explore patient goals, including continued CHCs (with or without treatment for bleeding irregularities) or discontinuation of CHCs. If the patient wants to continue CHCs, provide reassurance, discuss options for management of bleeding irregularities if it is desired, and advise the patient that they may contact their provider at any time to discuss bleeding irregularities or other side effects.

- If the patient wants to discontinue CHCs at any time, offer counseling on alternative contraceptive methods, and initiate another method if it is desired.

- If the patient wants treatment, the following treatment option may be considered:

- Advise the patient to discontinue CHC use (i.e., a hormone-free interval) for 3–4 consecutive days; a hormone-free interval is not recommended during the first 21 days of using the continuous or extended CHC method. A hormone-free interval also is not recommended more than once per month because contraceptive effectiveness might be reduced.

- Advise the patient to discontinue CHC use (i.e., a hormone-free interval) for 3–4 consecutive days; a hormone-free interval is not recommended during the first 21 days of using the continuous or extended CHC method. A hormone-free interval also is not recommended more than once per month because contraceptive effectiveness might be reduced.

Comments and Evidence Summary

During contraceptive counseling and before initiating extended or continuous CHCs, information about common side effects such as spotting or bleeding, especially during the first 3–6 months of use, should be discussed.[327] These bleeding irregularities are generally not harmful but might be bothersome to the patient. Bleeding irregularities usually improve with persistent use of the hormonal method. To avoid spotting or bleeding, counseling should emphasize the importance of correct use and timing; for users of contraceptive pills, emphasize consistent pill use. Enhanced counseling about expected bleeding patterns and reassurance that bleeding irregularities are generally not harmful has been demonstrated to reduce method discontinuation in clinical trials with other hormonal contraceptives (i.e., DMPA).[147],[148],[328]

A systematic review identified three studies with small study populations that addressed treatments for breakthrough bleeding among women using extended or continuous CHCs.[329] In two separate RCTs in which women were taking either contraceptive pills or using the contraceptive ring continuously for 168 days, women assigned to a hormone-free interval of 3 or 4 days reported improved bleeding. Although they noted an initial increase in flow, this was followed by an abrupt decrease 7–8 days later with eventual cessation of flow 11–12 days later. These findings were compared with those among women who continued to use their method without a hormone-free interval, in which a greater proportion reported either treatment failure or fewer days of amenorrhea.[330],[331] In another randomized trial of 66 women with breakthrough bleeding among women using 84 days of hormonally active contraceptive pills, oral doxycycline (100 mg twice daily) initiated the first day of bleeding and taken for 5 days did not result in any improvement in bleeding compared with placebo[332] (Level of evidence: I, fair, direct).