What to know

- Brucellosis is rare in people in the United States, so it's important to know how to recognize, diagnose, and treat the disease promptly.

- Without treatment, patients can develop serious chronic disease.

- Many species of Brucella bacteria can cause disease in humans, but the majority of cases are caused by just four. Therefore, risk factors, diagnostic tests, and treatment may vary.

Causes

Brucellosis in people is mostly caused by four species of Brucella bacteria. Most people get it through close contact with infected animals, often cows, pigs, feral swine, or dogs, or through consumption of contaminated animal products, including uncooked meat and raw milk products. Due to the long incubation period for Brucella, cases often don't have symptoms until weeks or months after exposure.

In the United States:

- B. melitensis and B. abortus comprise 70-75% of brucellosis cases and are caused by consumption of unpasteurized dairy products, such as raw milk and cheese. People likely get infected after consuming unpasteurized dairy products from abroad (either while traveling internationally or if family or friends bring products from abroad).

- A strain of B. abortus called RB51 is found in the Brucella livestock vaccine and rarely causes human infection. Cases that occur are most often associated with veterinary needle-stick exposures while vaccinating cattle. RB51 also passes into cow milk and can cause illness associated with consumption of raw milk products.

- B. suis infections account for 25-30% of brucellosis cases and are mostly diagnosed in people who hunt feral swine and contract it from butchering the carcass. Dogs also can contract brucellosis from feral swine and spread the infection to their owners.

- B. canis is the least common species found in people. It's transmitted by dogs around the world and generally causes mild illness in people when cases occur.

Signs, symptoms, and testing

Brucellosis is generally characterized by one or more of the following symptoms:

- Fever

- Headache

- Arthralgia

- Myalgia

- Fatigue

- Anorexia or weight loss

- Meningitis

- Focal organ involvement (endocarditis, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly)

Brucellosis in people cannot be diagnosed by clinical symptoms alone as initial symptoms are non-specific and can vary between patients. Laboratory testing is required to confirm a diagnosis.

If a patient has brucellosis symptoms, determining the route of exposure history can help you determine the right kind of laboratory testing (serology or culture, for instance).

- Did you recently consume raw (unpasteurized) milk or milk products? [B. melitensis, B. abortus, B. abortus RB51]

- Do you work in a slaughterhouse or meat-packing environment? [B. suis]

- Have you recently traveled overseas and did you eat unpasteurized (raw) milk products? [B. melitensis, B. abortus, B. abortus RB51]

- Have you had contact with moose, elk, caribou, bison or wild hogs? [B. suis]

- Have you assisted animals that were giving birth? [B. suis, B. canis]

- Do you work in a laboratory that handles Brucella specimens? [B. melitensis, B. abortus, B. abortus RB51, B. suis, B. canis]

Things to note:

- Most commercial clinical laboratories run serological tests that can detect antibodies to three Brucella species: B. abortus, B. melitensis, or B. suis.

- Some labs can also conduct culture tests on cerebrospinal fluid, purulent discharge, or joint fluid.

- Infection with B. canis and Brucella RB51 cannot be detected through serology testing, so labs will have to confirm the infection by these Brucellae with a culture.

- Some serology tests require two serum samples to confirm brucellosis, the first within 7 days of symptom onset, the second 2-4 weeks later to compare antibody levels.

- If having two sera samples isn't possible, you can make a probable diagnosis from a single sample.

Label samples appropriately!

If a laboratory is not available to perform culture and isolation, contact your state health department for help.

Samples may be sent to CDC for identification and molecular characterization. Contact your state health department to determine the appropriate route to submit samples. Be sure to follow the instructions for proper shipping.

Brucellosis is a reportable and nationally notifiable condition. Learn more about case definition, surveillance, and reporting.

Treatment and recovery

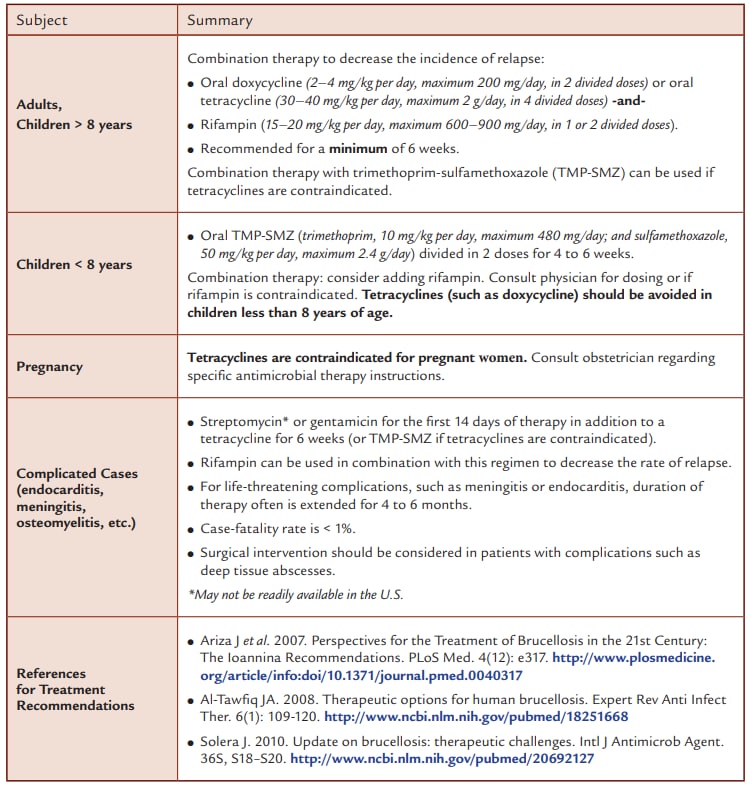

Once brucellosis has been confirmed by lab testing, start treatment immediately to help prevent chronic infection-associated arthritis, endocarditis, chronic fatigue, depression, and/or swelling of the liver or spleen.

B. melitensis, B. abortus, B. suis, and B. canis infections are typically treated with a combination of doxycycline and rifampin for at least 6 weeks.

However, rifampin should not be used for B. abortus RB51 infection, as that particular strain is resistant to it. Consider trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ) instead.

Antibiotic contraindications

Depending on the timing of treatment and severity of illness, recovery may take a few weeks to several months. Though the infection can last a long time, brucellosis rarely causes death. It's estimated that no more than 2% of all people with brucellosis die from their infection.

- Brucellosis 2010 CSTE Case Definition. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/brucellosis/case-definition/2010

- Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. 2009, positing date. Public health reporting and national notification for brucellosis, 09-ID-14. http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.cste.org/resource/ resmgr/PS/09-ID-14.pd

- Traxler RM, et al. 2013. Review of brucellosis cases from laboratory exposures in the United States in 2008 to 2011 and improved strategies for disease prevention. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51(9):3132–3136.

- The Laboratory Response Network—Partners in Preparedness. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.bt.cdc.gov/lrn/

- National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/

- Salata RA, Ravdin JI. 1985. Brucella species (brucellosis), p. 1283 – 1289. In Mandell GL, Douglas RG, Bennett JE, ed. Principles and practices of infectious diseases, 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York

- Glynn MK, Lynn TV. 2008. Zoonosis Update: Brucellosis. JAVMA 233(6): 900–908.

- World Health Organization. Brucellosis in humans and animals. 2007 http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/Brucellosis.pdf

- CDC. 2009. Brucella suis infection associated with feral swine hunting—three states, 2007-2008. MMWR. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5822a3.htm

- Ariza J et al. 2007. Perspectives for the Treatment of Brucellosis in the 21st Century: The Ioannina Recommendations. PLoS Med. 4(12): e317. http://www.plosmedicine.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040317

- Al-Tawfiq JA. 2008. Therapeutic options for human brucellosis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 6(1): 109-120. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18251668

- Solera J. 2010. Update on brucellosis: therapeutic challenges. Intl J Antimicrob Agent. 36S, S18–S20. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20692127