At a glance

- Hospital antibiotic stewardship programs promote the appropriate use of antibiotics to improve patient care and combat the threat of antimicrobial resistance.

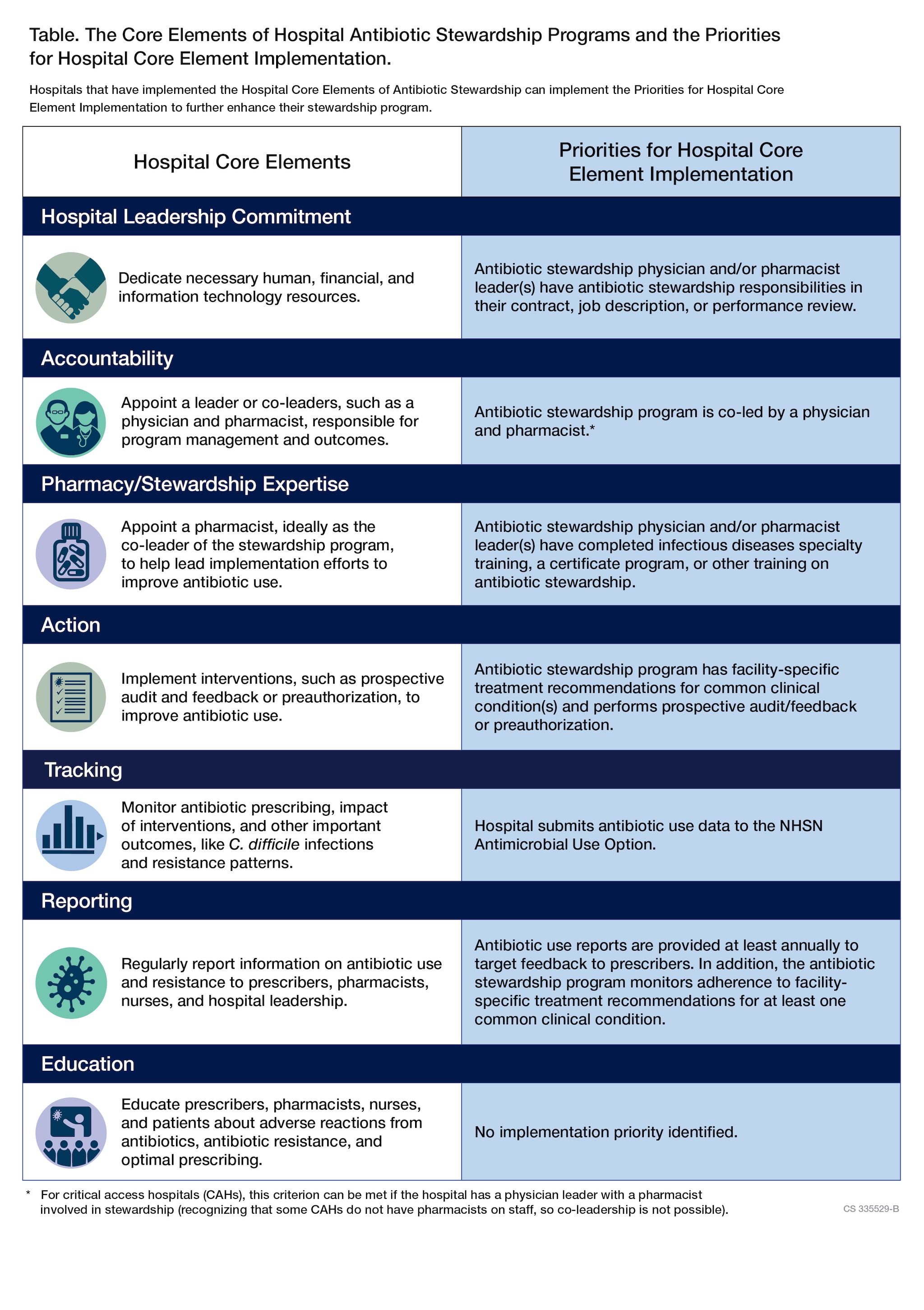

- The Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs outline structural and procedural components associated with successful antibiotic stewardship programs.

- Priorities for Hospital Core Element Implementation provide hospital leadership and antibiotic stewards opportunities to expand their antibiotic stewardship programs.

- Additional resources include practical strategies to implement antibiotic stewardship programs in small and critical access hospitals.

Overview

In 2019, CDC updated the 2014 Core Elements for Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs, which incorporates new evidence and lessons learned from experience with the Core Elements.

To continue enhancing hospital antibiotic stewardship programs, CDC has released Priorities for Hospital Core Element Implementation (Priorities) in 2022 to help enhance the quality and impact of existing antibiotic stewardship programs. The Priorities highlight highly effective implementation approaches and are supported by evidence and stewardship experts.

The Core Elements are applicable in all hospitals, regardless of size. There are suggestions specific to small and critical access hospitals in Implementation of Antibiotic Stewardship Core Elements at Small and Critical Access Hospitals.

Core Elements documents

Implementation resources

Below are additional CDC and external resources that can support Core Elements implementation in hospital settings.

Hospital leadership commitment

Dedicate necessary human, financial, and information technology resources.

Accountability

Appoint a leader or co-leaders, such as a physician and pharmacist, responsible for program management and outcomes.

Pharmacy expertise

Appoint a leader or co-leaders, such as a physician and pharmacist, responsible for program management and outcomes.

Action

Implement interventions, such as prospective audit and feedback or preauthorization, to improve antibiotic use.

Guidance and toolkits

- Implementing an Antibiotic Stewardship Program: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America | IDSA

- Antimicrobial Stewardship Transition of Care | Henry Ford Health System

- Toolkit to Enhance Nursing and Antibiotic Stewardship Partnership | Johns Hopkins Medicine

- Redefining the Antibiotic Stewardship Team: Recommendations from the American Nurses Association (ANA)/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Workgroup on the Role of Registered Nurses in Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Practice | ANA, CDC

- Toolkit To Improve Antibiotic Use in Acute Care Hospitals | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Diagnostic stewardship and microbiology resources

- Prevent Adult Blood Culture Contamination | Laboratory Quality

- Key Activities and Roles for Microbiology Laboratory Staff in Antibiotic Stewardship Programs

- Selective Reporting of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Results: A Primer for Antibiotic Stewardship Programs

- Indwelling Urinary Catheter Culture Stewardship

Tracking

Monitor antibiotic prescribing, impact of interventions, and other important outcomes, like C. difficile infections and resistance patterns.

- National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Antimicrobial Use and Resistance (AUR) Module

- Strategies to assess antibiotic use to drive improvements in hospitals

- Leveraging National Health Safety Network Antibiotic Use Data to Inform, Implement and Assess Antibiotic Stewardship Activities | Duke Antimicrobial Stewardship Outreach Network

- Inappropriately Broad Empiric Antibiotic Selection for Adult Hospitalized Patients with Uncomplicated Community-Acquired Pneumonia | Partnership for Quality Measurement

- Excess Antibiotic Duration for Adult Hospitalized Patients with Uncomplicated Community-Acquired Pneumonia | Partnership for Quality Measurement

- Electronic Feedback Reports: An Implementation Toolkit for Adult and Pediatric Antibiotic Stewardship Programs I University of Pennsylvania Health System

Reporting

Regularly report information on antibiotic use and resistance to prescribers, pharmacists, nurses, and hospital leadership.

- Mapping of the Patient Safety Component – Annual Hospital Survey

- How to run the Hospital Core Elements Line List in NHSN

- How to Run the Priorities Line List in NHSN

Education

Educate prescribers, pharmacists, nurses, and patients about adverse reactions from antibiotics, antibiotic resistance, and optimal prescribing.

- Antibiotic Stewardship Courses | CDC

- Online Primer on Healthcare Epidemiology, Infection Control & Antimicrobial Stewardship | The Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA)

- Antimicrobial Stewardship Training Programs | Making a Difference in Infectious Diseases (MAD-ID)

- Antimicrobial Stewardship Certificate Program | Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists (SIDP)

- Antibiotic Stewardship Resources | Pediatric Infectious Disease Society (PIDS)

- Core Antimicrobial Stewardship Curriculum | IDSA Academy

Additional resources

The National Quality Partners Playbook: Antibiotic Stewardship in Acute Care | National Quality Forum

![[thumbnail] (hidden)](/antibiotic-use/media/images/hospital-core-elements-thumb.jpg)

![[thumbnail] (hidden)](/antibiotic-use/media/images/assessment-tool-thumb.jpg)

![[thumbnail] (hidden)](/antibiotic-use/media/images/core-elements-small-critical-thumb.jpg)