Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail.

Progress Toward Poliomyelitis Eradication --- Nigeria, January 2009--June 2010

Nigeria has maintained a high incidence of wild poliovirus (WPV) cases attributed to persistently high proportions of under- and unimmunized children, and, for many years, the country has served as a reservoir for substantial international spread (1). In 2008, Nigeria reported 798 polio cases, the highest number of any country in the world (2). This report provides an update on poliovirus epidemiology in Nigeria during the past 18 months, January 2009--June 2010, and describes activities planned to interrupt transmission. Reported WPV cases in Nigeria decreased to 388 during 2009 (24% of global cases), and WPV incidence in Nigeria reached an all-time low during January--June 2010, with only three reported cases. Cases of circulating type 2 vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV2), which first occurred in Nigeria in 2005 (3), also declined, from 148 during the 12 months of 2009, to eight during the 6-month period, January--June 2010. One indicator of the effectiveness of immunization activities is the proportion of children with nonpolio acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) who never have received oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV). In seven high-incidence northern states of Nigeria, this proportion declined from 17.6% in 2008 to 10.7% in 2009. During 2009--2010, increased engagement of traditional, religious, and political leaders has improved community acceptance of vaccination and implementation of high-quality supplementary immunization activities (SIAs). Enhanced surveillance for polioviruses, further strengthened implementation of SIAs, and immediate immunization responses to newly identified WPV and cVDPV2 cases will be pivotal in interrupting WPV and cVDPV2 transmission in Nigeria.

Immunization Activities

Routine immunization against polio in Nigeria consists of trivalent OPV (tOPV, types 1, 2, and 3) at birth and at ages 6, 10, and 14 weeks. Immunization coverage is measured using both administrative data (estimated doses administered per targeted child population, determined by official census numbers) and coverage surveys. In 2009, using administrative data, national routine immunization coverage of children by age 12 months with three tOPV doses was 63% (range by state: 35%--90%) (4). Using coverage surveys, the estimated national coverage with three tOPV doses at 12--23 months was 39%, but lower in the northeast (28.6%) and northwest (24.3%) areas of Nigeria, including the seven high-incidence northern states (5).*

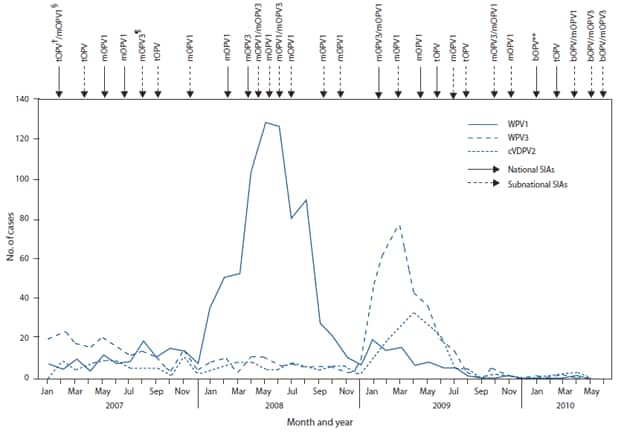

In addition to routine immunization, Nigeria conducts SIAs† for polio eradication using monovalent OPV type 1 (mOPV1), monovalent OPV type 3 (mOPV3), bivalent OPV types 1 and 3 (bOPV), or tOPV. Monovalent vaccines are more effective than tOPV in providing protection against the corresponding WPV serotype; bOPV is nearly equivalent to mOPV and superior to tOPV in producing seroconversion to WPV1 and WPV3 (6). Three national SIAs were conducted in 2009, using mOPV3, mOPV1, and tOPV. Five subnational SIAs were conducted in 2009, each using mOPV1, mOPV3, tOPV, or both mOPV1 and mOPV3. During January--June 2010, two national SIAs were conducted, one with bOPV and one with tOPV; bOPV, mOPV1, and mOPV3 were used in three subnational SIAs (Figure 1).

Vaccination histories of children with nonpolio AFP are used to estimate OPV coverage among the population of children aged 6--59 months. The proportion of children with nonpolio AFP reported to have never received an OPV dose (zero-dose children) from the seven high-incidence northern states declined from 17.6% in 2008 to 10.7% in 2009 (range: 0%--17.0%), with the highest proportions occurring in Zamfara and Kano states (Table). In contrast, the proportion of reported zero-dose children was 2.2% in 13 other northern states and 1.8% in 17 southern states in 2009. The proportion of children with nonpolio AFP reported to have received ≥4 OPV doses was 37.4% in the seven high-incidence northern states and 60.8% for the entire country.

AFP Surveillance

AFP surveillance is monitored using World Health Organization (WHO) targets for case detection and adequate stool specimen collection.§ The national annualized nonpolio AFP detection rate among children aged <15 years was 8.2 per 100,000 during January--March 2009 and 9.0 per 100,000 during January--March 2010. Nonpolio AFP detection rates meeting the WHO target were achieved in all 37 Nigerian states during January--December 2009 and in all but one state (Plateau) during January--March 2010.

The WHO adequate stool specimen target was reached in all 37 states and in 683 (88%) of 776 local government areas (LGAs) during January--December 2009, and in 36 states and 557 (72%) LGAs during January--March 2010. The proportion of LGAs meeting both surveillance indicators (nonpolio AFP detection rate meeting the target and adequate stool specimen collection rate) rose from 78% in 2008 to 86% in 2009.

WPV and cVDPV Incidence

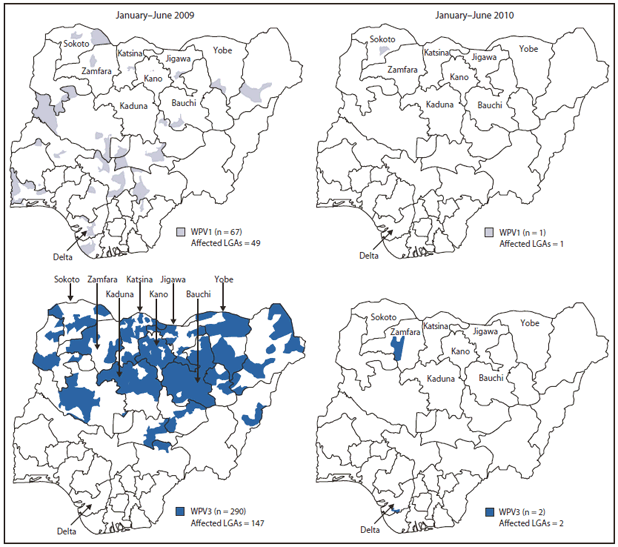

Reported WPV type 1 (WPV1) cases declined from 67 during January--June 2009 to seven during July--December 2009, and to one case during January--June 2010 (provisional data, as of July 5, 2010) (Figure 2). Of the 75 WPV1 cases reported during the entire 18-month period, January 2009--June 2010, seven (9%) occurred in the seven high-incidence northern states, 33 (44%) in other northern states, and 35 (47%) in southern states. The number of LGAs with WPV1 cases declined from 49 during January--June 2009 to one during January--June 2010 (Figure 2). Reported WPV type 3 (WPV3) cases declined from 290 during January--June 2009 to 24 during July--December 2009, and to two during January--June 2010. Only three cases of WPV have been reported during the first 6 months of 2010. Among 316 WPV3 cases reported from January 2009--June 2010, 240 (76%) occurred in the high-incidence northern states, 75 (24%) in other northern states, and one (<1%) in southern states. The number of LGAs with WPV3 cases declined from 147 in January--June 2009 to two during January--June, 2010 (Figure 2). Of 391 WPV cases reported with onset during January 2009--June 2010, 270 (69%) occurred in children aged <3 years, 266 (68%) were in children reported to have received <4 OPV doses, and 66 (17%) were in zero-dose children. The number of cVDPV2 cases declined from 137 during January--June 2009 to 11 during July--December 2009, and to eight during January--June 2010.

All WPV isolates undergo partial genomic sequencing to determine genetic relatedness. Each 1% difference between two isolates correlates with approximately 1 year of undetected circulation between the specific chains of transmission. Differences greater than 1.5% indicate potential quality issues for surveillance. Three of the seven WPV1 isolates from July--December 2009 cases and the one WPV1 isolate from 2010 exhibited >1.5% divergence from the closest predecessor. Similarly, nine of the 24 (38%) WPV3 isolates from July--December 2009 and both 2010 WPV3 exhibited ≥1.5% divergence.

Reported by

National Primary Health Care Development Agency and Federal Ministry of Health; Country Office of the World Health Organization, Abuja; Poliovirus Laboratory, Univ of Ibadan, Ibadan; Poliovirus Laboratory, Univ of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital, Maiduguri, Nigeria. African Regional Polio Reference Laboratory, National Institute for Communicable Diseases, Johannesburg, South Africa. Vaccine Preventable Diseases, World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa, Brazzaville, Congo. Polio Eradication Dept, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. Div of Viral Diseases and Global Immunization Div, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC.

Editorial Note

Since 2003, Nigeria has served as the major reservoir for WPV1 and WPV3 circulation in West Africa and Central Africa (7). Over the past 8 years, WPV of Nigerian origin has been imported into 26 countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, and has led to reestablished transmission (>12 months) in Chad and Sudan.

Factors related to high WPV incidence in Nigeria during the last decade have included loss of public confidence in OPV during 2003--2004 (8), long-standing insufficiencies in health infrastructure resulting in low routine vaccination coverage, and poorly implemented SIAs that have failed to reach >80% of children in high-risk states. With substantial reductions in WPV1, WPV3, and cVDPV2 cases during January--June 2010 compared with the same period in 2009, Nigeria has shown substantial progress, suggesting improvements in vaccine coverage with high-quality SIAs. The increased engagement of traditional, religious, and political leadership at the federal, state, and local levels has been instrumental in improving vaccine acceptance and SIA implementation. If this progress can be sustained throughout the upcoming season (July--September), during which WPV transmission is traditionally high, WPV transmission in Nigeria could be disrupted in the near future. Progress elsewhere, including successful implementation of synchronized SIAs in West Africa and Central Africa to stem regional WPV circulation, would remove a potential threat of reimportation into Nigeria and ultimately lead to a polio-free Africa. However, multiple challenges must be overcome to sustain the gains in Nigeria.

Within the seven high-incidence northern states, a high proportion of children remain at risk as a result of low routine immunization coverage and high birth rates. This report indicates that, during 2008--2009, a substantial drop occurred in the proportion of children with nonpolio AFP who had received no doses of vaccine (i.e., from 17.6% in 2008 to 10.7% in 2009) in the seven high-incidence states. However, even with this decrease, in 2009, a majority of such children (50.7%) remained undervaccinated with 1--3 doses of OPV. Until the proportion of children vaccinated with ≥4 doses is >80% and the proportion of zero-dose children is <10% in each state, the risk remains that WPV transmission will continue (9).

The quality of SIA implementation remains variable and highly dependent on LGA commitment and resources, including timely disbursement of funds in support of SIAs. Successful implementation of SIAs planned for the remainder of 2010 will require ongoing engagement of LGA leadership and supervision, with close monitoring of performance indicators at the LGA, state, and federal levels. Since emerging in 2005--2006, cVDPV2 continues to circulate in northern Nigeria. Continued use of high-quality SIAs with tOPV will be needed to further control and eliminate cVDPV2 transmission, while routine immunization services are strengthened. Any new WPV case should trigger rapid, type-specific vaccination responses ("mop-up" SIAs).

Genomic sequence analysis indicates that some chains of WPV transmission during 2009--2010 have not been detected for more than a year, suggesting limitations in surveillance quality despite AFP surveillance performance indicators meeting or exceeding targets at national and virtually all state levels. Surveillance gaps might be occurring among specific subpopulations such as migrants in northern Nigeria, including Fulani nomads, who have limited access to immunization activities and health-care providers. Further efforts to enhance and supplement AFP surveillance to detect WPV and cVDPV should include seeking reports from nontraditional healers, testing waste water for polioviruses, and identifying and improving surveillance in LGAs not meeting performance criteria.

References

- CDC. Wild poliovirus type 1 and type 3 importations---15 countries, Africa, 2008--2009. MMWR 2009;58:357--62.

- CDC. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication---Nigeria, 2008--2009. MMWR 2009;58:1150--4.

- CDC. Update on vaccine-derived polioviruses---worldwide, January 2008--June 2009. MMWR 2009;58:1002--6.

- World Health Organization. Immunization surveillance, assessment, and monitoring. country immunization profile---Nigeria. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. Available at http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/en/globalsummary/countryprofileselect.cfm. Accessed June 11, 2010.

- ICF Macro. Nigeria, 2008 demographic health survey, key findings. Calverton, MD: ICF Macro; 2008. Available at http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/sr173/sr173.pdf. Accessed February 26, 2010.

- World Health Organization. Advisory Committee on Poliomyelitis Eradication: recommendations on the use of bivalent oral poliovirus vaccine types 1 and 3. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2009;84:289--90.

- CDC. Progress toward interruption of wild poliovirus transmission---worldwide, 2009. MMWR 2010;59:545--50.

- Jegede AS. What led to the Nigerian boycott of the polio vaccination campaign? PLoS Med 2007;4(3):e73.

- Jenkins HE, Aylward RB, Gasasira A, et al. Effectiveness of immunization against paralytic poliomyelitis in Nigeria. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1666--74.

* For this report, high-incidence northern states are defined as states with ≥0.8 confirmed WPV cases per 100,000 population during 2008. They are Bauchi, Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Yobe, and Zamfara.

† Mass campaigns conducted during a short period (days to weeks) during which a dose of OPV is administered to all children aged <5 years, regardless of previous vaccination history. Campaigns can be conducted nationally or in portions of the country (i.e., subnational SIAs).

§ AFP cases in children aged <15 years and suspected poliomyelitis in persons of any age are reported and investigated, with laboratory testing, as possible polio. WHO operational targets for countries at high risk for poliovirus transmission are a nonpolio AFP rate of at least two cases per 100,000 population aged <15 years at each subnational level and adequate stool specimen collection for >80% of AFP cases (i.e., two specimens collected at least 24 hours apart, both within 14 days of paralysis onset, and shipped on ice or frozen ice packs to a WHO-accredited laboratory and arriving at the laboratory in good condition).

What is already known on this topic?

In 2008, 798 cases of wild poliovirus (WPV) (48% of global cases) were reported in Nigeria, one of four remaining countries (including India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan) that have never eliminated WPV transmission of both serotypes 1 and 3.

What is added by this report?

From 2008 to 2009, cases of WPV in Nigeria declined substantially (from 798 cases to 388), now accounting for <1% of reported global WPV cases, and during the first 6 months of 2010, only three WPV cases were reported. Among children with nonpolio acute flaccid paralysis, the decline from 17.6% in 2008 to 10.7% in 2009 of zero-dose children in high-incidence northern states indicates that population immunity might be steadily increasing in areas that traditionally have been responsible for extensive WPV transmission.

What are the implications for public health practice?

With sustained support of traditional, religious, and political leaders to improve implementation of polio vaccination activities and to improve surveillance for polio cases, Nigeria has the potential to eliminate WPV transmission in the near future.

FIGURE 1. Number of laboratory-confirmed cases, by wild poliovirus (WPV) type or circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) and month of onset, type of supplementary immunization activity (SIA),* and type of vaccine administered --- Nigeria, January 2007--June 2010

* Mass campaign conducted during a short period (days to weeks) during which a dose of oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) is administered to all children aged <5 years, regardless of previous vaccination history. Campaigns can be conducted nationally or in portions of the country.

† Trivalent OPV.

§ Monovalent OPV type 1.

¶ Monovalent OPV type 3.

** Bivalent OPV.

Alternate Text: The figure above shows the number of laboratory-confirmed cases, by wild poliovirus (WPV) type or circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) and month of onset, type of supplementary immunization activity (SIA), and type of vaccine administered in Nigeria from January 2007-June 2010. Three national SIAs were conducted in 2009, using mOPV3, mOPV1, and tOPV. Five subnational SIAs were conducted in 2009, each using mOPV1, mOPV3, tOPV, or both mOPV1 and MOPV3. During January-June 2010, two national SIAs were conducted, one with bOPV and one with tOPV; bOPV, mOPV1, and mOPV3 were used in three subnational SIAs.

FIGURE 2. Local government areas (LGAs) with laboratory-confirmed cases of wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) and type 3 (WPV3) --- Nigeria, January--June 2009 and January--June 2010*

* During 2008, Bauchi, Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Yobe, and Zamfara had ≥0.8 confirmed WPV cases per 100,000 population and were defined as high-incidence northern states. During January--June 2010, confirmed WPV1 in Nigeria occurred only in Sokoto, and WPV3 occurred only in Delta and Zamfara.

Alternate Text: The figure above shows local government areas (LGAs) with laboratory-confirmed cases of wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) and type 3 (WPV3) in Nigeria from January-June 2009 and January-June 2010. Reported WPV1 cases declined from 67 during January-June 2009 to seven during July-December 2009, and to one case during January-June 2010 (provisional data, as of July 5, 2010).

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services.

References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are

provided as a service to MMWR readers and do not constitute or imply

endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content

of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed in MMWR were current as of

the date of publication.

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents.

This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version.

Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr)

and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables.

An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S.

Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371;

telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

**Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to

mmwrq@cdc.gov.