At a glance

On March 24, 1882, Dr. Robert Koch announced the discovery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the germ that causes tuberculosis (TB). A century later, in 1982, the global health community recognized March 24 as World TB Day.

Overview

In 1882, TB disease killed one in seven people in the United States and Europe.

Dr. Koch's discovery was significant in the effort to eliminate TB disease. Since its discovery, the health community has learned more about this deadly disease.

Names for TB

What is in a name?

During ancient times, TB disease had several names. For example, people referred to TB disease as:

- "Phthisis" in ancient Greek,

- "Tabes" in ancient Latin, and

- "Schachepheth" in ancient Hebrew.

During the Middle Ages, health care providers referred to active TB disease of the neck and lymph nodes as "scrofula."

In the 1700s, people referred to TB disease as "the white plague" due to the pale complexion of people with TB disease.

In the 1800s, people called TB disease "consumption." In 1834, Johann Schonlein named the disease "tuberculosis."

In 1909, Clemens von Pirquet invented the term "latent TB infection" to refer to inactive TB.

Names for TB today

Today, health care providers and public health professionals use additional terms to describe if and where TB germs are growing in the body, and the medicines that will kill the germs.

Today, the names for TB describe its:

- Condition type (i.e., inactive TB or active TB disease),

- Location (i.e., pulmonary or extrapulmonary), and

- Treatment type (i.e., drug-susceptible, drug-resistant, multidrug-resistant, pre-extensively drug-resistant, or extensively drug-resistant.)

TB in animals

TB is not just a disease found in humans.

Mycobacterium bovis (Bovine TB) is a member of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex commonly associated with cattle and deer. It can infect other mammals, including humans, causing disease similar to M. tuberculosis.

Today, M. bovis rarely affects people in the United States. Human cases are often linked to consuming contaminated foods, such as unpasteurized milk or dairy products. Before pasteurization became common practice, humans usually were infected with these TB germs through contaminated milk.

TB in humans

TB has been part of the human experience for a long time.

TB germs in humans traces back to 9,000 years ago. Archeologists found TB germs in the remains of a mother and child in Atlit Yam, a city now submerged under the Mediterranean Sea off the coast of Israel.

The earliest written records of TB disease were in India (3,300 years ago) and China (2,300 years ago).

During the 1600s to 1800s, TB disease caused 25% of all deaths in Europe. Similar numbers occurred in the United States.

Counting cases of TB disease

In 1889, Dr. Hermann Biggs convinced the New York City Department of Health and Hygiene that doctors should report cases of TB disease. The health department published the first report on TB disease in 1893.

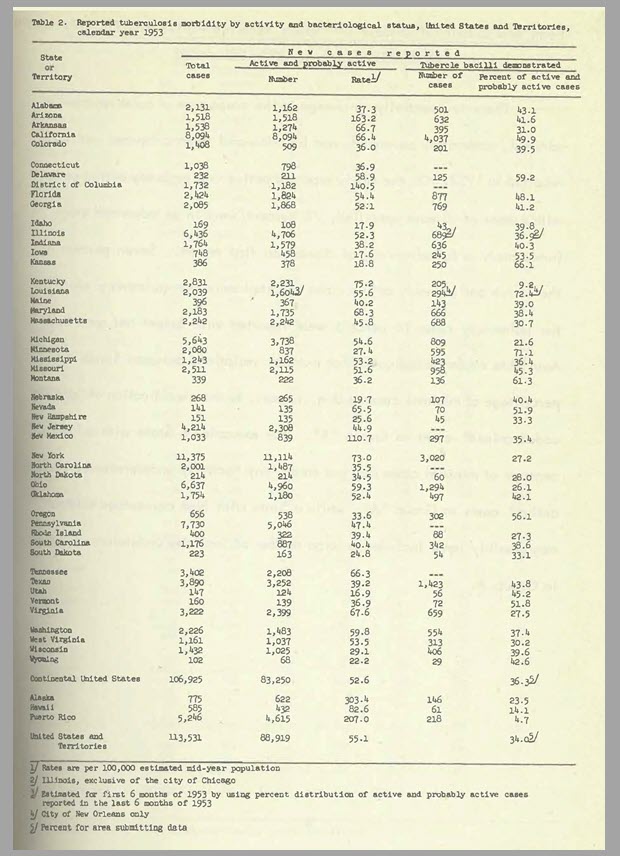

Public health programs report new cases of TB to CDC through the National Tuberculosis Surveillance System (NTSS). Since 1953, NTSS has collected information on all newly reported cases of TB disease in the United States. CDC published the first nationwide report on cases of TB disease in 1953. At that time, the United States reported a total of 84,304 cases of TB disease.

In 1993, NTSS began maintaining reported information in an electronic database. Every year, CDC publishes an annual report on reported TB disease in the United States.

TB disease is a nationally notifiable disease, meaning TB programs must report cases of TB disease to CDC. CDC does not require TB programs to report cases of latent TB infection (also known as inactive TB).

Ending TB in the United States will require a dual approach of maintaining and strengthening current TB priorities while increasing efforts to identify and treat inactive TB in populations at risk for active TB disease.

How TB disease spreads

Do vampires cause TB?

Before scientists discovered the germ that causes TB, people believed TB disease was hereditary or passed down from a parent.

In the early 1800s, outbreaks of TB disease sparked "vampire panics" throughout New England. Some people believed that the first family member to die of TB disease came back as a vampire to infect the rest of the family. To stop the vampires, townspeople dug up the suspected vampire grave and performed a ritual.

On March 24, 1882, at the Berlin Physiological Society conference, Dr. Robert Koch announced during his presentation "Die Aetiologie der Tuberculose" that germs cause active TB disease. The discovery of TB germs proved that TB disease was an infectious disease, not hereditary. In 1905, Dr. Koch won the Nobel Prize for Medicine and Physiology for the discovery.

What we know today

Today, we know that TB is spread through the air from one person to another. The TB germs are spread into the air when a person with TB disease of the lungs or throat coughs, speaks, or sings. People may breathe in these TB germs and become infected.

People with TB disease are most likely to spread it to people they spend time with every day. This includes family members, friends, coworkers, or schoolmates. Health department staff may contact people who have spent time with a person with TB disease to let them know they may have been exposed to TB germs and should get tested. This is called a contact investigation.

Technologies like whole-genome sequencing give TB programs information to prevent the spread of TB disease.

Testing

Finding TB is the first step towards ending TB.

In 1890, Robert Koch developed tuberculin (an extract of the TB bacilli) as a cure for TB disease. However, it proved to be ineffective. In 1907, Clemens von Pirquet developed a skin test that put a small amount of tuberculin under the skin and measured the body's reaction. In 1908, Charles Mantoux updated the skin test method by using a needle and syringe to inject the tuberculin.

In the 1930s, American Florence Seibert, PhD developed a process to create a purified protein derivative (PPD) of tuberculin. Before this, the tuberculin used in TB skin tests was not consistent or standardized. Seibert did not patent the technology, but the United States government adopted it in 1940.

TB programs and health care providers still use the TB skin test today and it is virtually unchanged. The World Health Organization lists the TB skin test and PPD on its essential medicines list.

TB blood tests (also called interferon-gamma release assays or IGRAs) are a recent advancement in TB testing. The tests measure how your immune system reacts when a small amount of your blood is mixed with TB proteins.

Today, health care providers use the TB blood test or the TB skin test for TB infection. If the test is positive, the health provider will do other tests to diagnose inactive TB or active TB disease.

TB vaccine

Albert Calmette and Jean-Marie Camille Guérin developed the bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine in 1921. Prior to developing the BCG vaccine, Calmette developed the first antivenom to treat snake venom.

The vaccine is not generally used in the United States. It is given to infants and small children in countries where TB is common. It protects children from getting severe forms of active TB disease, such as TB meningitis. The vaccine's protection weakens over time. TB blood tests are the preferred TB test for people who have received the BCG vaccine.

Vaccine research continues into the future. A more effective TB vaccine could reduce TB disease and deaths worldwide.

Treatment

"Lana, letto, latte"

Until the discovery of antibiotics, TB treatment included warmth, rest, and good food, or "lana, letto, latte" in Italian.

In the Middle Ages, treatment for scrofula (TB disease of the lymph nodes and neck) was the "royal touch." People believed that a touch from English and French kings and queens could cure the disease. People would line up in hopes that a touch from the sovereign would result in a cure for TB disease.

In the early 1800s, treatments for TB disease included:

- Consuming cod liver oil,

- Receiving vinegar massages, and

- Inhaling hemlock or turpentine.

Antibiotics were a major breakthrough in TB treatment. In 1943, Selman Waksman, Elizabeth Bugie, and Albert Schatz developed the antibiotic streptomycin. Waksman received the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1952 for this discovery.

Today, TB is preventable and curable.

There are several safe and effective treatment plans recommended in the United States for inactive TB and active TB disease. A TB treatment plan (also called treatment regimen) is a schedule to take TB medicines to kill all the TB germs.

Inactive TB

If you have inactive TB, treating it is the best way to protect you from getting sick with active TB disease.

Treatment for inactive TB can take three, four, six, or nine months depending on the treatment plan. The treatment plans for inactive TB use different combinations of medicines that may include:

- Isoniazid

- Rifampin

- Rifapentine

Active TB disease

If you have active TB disease, you can be treated with medicine. There are several safe and effective treatment plans recommended in the United States for active TB disease.

Treatment for active TB disease can take four, six, or nine months depending on the treatment plan. The treatment plans for active TB disease use different combinations of medicines that may include:

- Ethambutol

- Isoniazid

- Moxifloxacin

- Rifampin

- Rifapentine

- Pyrazinamide

Sanatoriums

Before antibiotics, the best medicine for TB disease was isolation and proper nutrition.

TB sanatoriums were places where people received treatment for TB disease. People with TB disease received treatment away from their home, which reduced the risk of spreading TB germs to their friends and families.

Treatment for TB disease in sanatoriums included:

- Fresh air,

- Good food, and

- Sometimes surgery.

19th century

In 1875, Joseph Gleitsmann opened the first sanatorium in the United States in Asheville, North Carolina.

Then, in 1884, Edward Livingston Trudeau, who had TB disease himself, opened the second U.S. TB sanatorium called Adirondack Cottage Sanatorium in Saranac, New York. In 1894, Trudeau built the first laboratory in the United States for the research of TB. He later died from TB disease.

20th century

During the 20th century, America built many sanatoriums to care for people with active TB disease. In 1904, the United States had 115 sanatoriums with the capacity for 8,000 patients. This number grew to 839 sanatoriums with the capacity for 136,000 patients in 1953.

In 1907, social worker Emily Bissel wanted to help raise money for a local sanatorium. She designed the first "Christmas Seals" stamp and sold them for a penny. The first year, she raised $3,000 – 10 times what she hoped to collect! This began the tradition of selling Christmas Seals to raise money for TB sanatoriums.

In the 1950s, a study in Madras, India showed that it was possible to treat people with TB disease at their home with proper drug therapy.

21st century

Today, sanatoriums are no longer in use in the United States. People with active TB disease and inactive TB receive treatment from a health care worker and may take medicine through:

- Directly observed therapy (DOT),

- On their own, or

- A combination of both.

Through DOT, a person with TB meets with a health care worker every day or several times a week. These meetings may be in-person or virtual (through a smartphone, tablet, or computer). The health care worker will watch person with TB take TB medicines and make sure that the medicines are working as they should.

Policy/organization

Dedicated people, agencies, and organizations continue efforts to eliminate TB.

In 1904, Edward Trudeau founded the National Association for the Study and Prevention of TB. In 1905, he founded the American Sanatorium Society. Today, these organizations are the American Lung Association and the American Thoracic Society, respectively.

A resurgence of TB disease in the early 1990s led the Institute of Medicine to publish the report, "Ending Neglect," in 2000. This report was significant for TB control in the United States because it outlined necessary steps to eliminate TB disease.

CDC works to eliminate TB in the United States along with other health departments, TB programs, and local and national organizations, including:

- American Lung Association. The History of Christmas Seals. http://www.christmasseals.org/history/. Accessed Feb 13 2018.

- Barberis, I., Bragazzi, NL., Galluzzo, M., Martini, M. The history of tuberculosis: from the first historical records to the isolation of Koch's bacillus. J Prev Med Hyg. 2017; 58:E9-E12.

- Daniel TM. The history of tuberculosis. Respir Med. 2006;100(11):1862-1870. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2006.08.006

- Daniel TM. Florence Barbara Seibert and purified protein derivative. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13(3):281-282.

- Daniel TM, Iversen PA. Hippocrates and tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19(4):373-374. doi:10.5588/ijtld.14.0736

- Eddy JJ. The ancient city of Rome, its empire, and the spread of tuberculosis in Europe. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2015;95 (Suppl 1):S23-S28. doi:10.1016/j.tube.2015.02.005

- Fogel N. Tuberculosis: a disease without boundaries. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2015;95(5):527-531. doi:10.1016/j.tube.2015.05.017

- Frith, J. History of Tuberculosis. Part 1 – Phthisis, consumption and the White Plague. Journal of Military and Veteran's Health. 2014; 22(2):29-35

- Institute of Medicine. Ending Neglect: The Elimination of Tuberculosis in the United States. Washington D.C., United States: National Academy Press; 2000

- Lougheed, K. Catching Breath: The Making and Unmaking of Tuberculosis. London, Great Britain: Bloomsbury Sigma Publishing; 2017

- Murray JF., Schraufnagel DE., Hopewell, PC. Treatment of Tuberculosis: A Historical Perspective. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015; 12(12):1749-1759

- Patterson, S., Drewe, JA., Pfeiffer, DU, Clutton-Brock, TH. Social and environmental factors affect tuberculosis related mortality in wild meerkats. J of Anim Ecol. 2017; 86:442-450.

- Perrin, P. Human and tuberculosis co-evolution: An integrative view. Tuberculosis. 2015; 95:S112-S116

- Rom WN, Reibman J. The History of the Bellevue Hospital Chest Service (1903-2015). Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(10):1438-1446. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201506-370PS

- Riva MA. From milk to rifampicin and back again: history of failures and successes in the treatment for tuberculosis. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 2014;67(9):661-665. doi:10.1038/ja.2014.108

- Rothschild, BM, Martin, LD, Lev, G, Bercovier, H, Bar-Gal, GK, Greenblatt,C, Donoghue, H, Spigelman, M, Brittain, D. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Complex DNA from an Extinct Bison Dated 17,000 Years before the Present. Clin Infect Dis. 2001; 33:305–11

- Ruggerio, D. A Glimpse at the Colorful History of TB: Its Toll and Its Effect on the U.S. and the World. TB Notes 2000. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2000 Atlanta GA.

- Towey, F. Historical Profile Leon Charles Albert Calmette and Jean-Marie Camille Guerin. Lancet. 2015; 3:186-187

- Tucker, A. The Great New England Vampire Panic. Smithsonian.com. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-great-new-england-vampire-panic-36482878/. Accessed Feb 2018.

- United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. Bovine Tuberculosis Disease Information. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/cattle/bovine-tuberculosis-cattle. Accessed Dec 6 2024.