At a glance

- There is no safe level of exposure to secondhand smoke (SHS).

- African American children and adults are more likely to be exposed to secondhand smoke than any other racial or ethnic group.

- There are actions that can be taken to protect people from secondhand smoke.

Overview

CDC is focused on protecting all people from health risks—including secondhand smoke, or the smoke produced when commercial tobacco is burned—where they work, live, and play.AThere is no safe level of exposure to secondhand smoke.1

Smoke-free air policies are important because they protect people who do not smoke from secondhand smoke, motivate those who smoke to quit, and prevent people from starting to smoke. Right now, however, not everyone in the nation is equitably protected by commercial tobacco control policies. Of the 10 US states with the highest proportion of Black residents, 2 states have laws that prevent local communities from setting up stronger smoke-free policies and 5 states have laws that prevent local communities from setting up other commercial tobacco control policies.23

- African American children and adults are more likely to be exposed to secondhand smoke than any other racial or ethnic group.4

- African American people who don't smoke generally have higher levels of cotinine (a chemical found in the body that means a person has been exposed to tobacco smoke) than people of other races/ethnicities who don't smoke.4

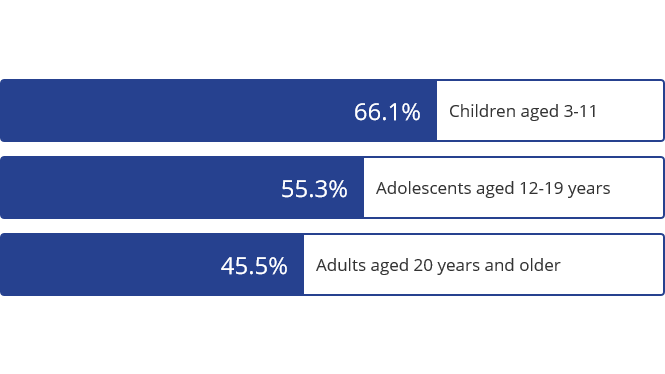

- During 2013–2014, secondhand smoke exposure among African American people was found in:4

The following actions can be taken to protect people from secondhand smoke:

- Adopt and expand smoke-free home policies, while making support for people who want to quit smoking more available. When landlords adopt smoke-free building policies, it protects tenants from secondhand smoke exposure and increases their chances of quitting tobacco long-term.5

- Let local communities create stronger smoke-free air policies. In some states that do not have a statewide smoke-free policy, communities have put in place comprehensive smoke-free laws. 6However, 1 in 5 people who aren't protected by a smoke-free policy live in a state that does not allow local communities to have their own smoke-free laws.7 Research has reported that, compared to other racial and ethnic groups, the proportion of non-Hispanic Black people protected by smoke-free laws is lower because they are more likely to live in Southern and Midwestern states (states where tobacco is grown and where there are fewer smoke-free laws).7 This 2013 study showed that only 41% of non-Hispanic Black people were covered by smoke-free restaurant and bar laws in the U.S. Letting local governments adopt smoke-free policies would let more communities protect residents from secondhand smoke.

- "Commercial tobacco" means harmful products that are made and sold by tobacco companies. It does not include "traditional tobacco" used by Indigenous groups for religious or ceremonial purposes.

- U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, 2014. Accessed January 19, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK179276/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STATE System Preemption Fact Sheet. Accessed September 23, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/statesystem/factsheets/preemption/Preemption.html

- U.S. Dept of Census. Race and Ethnicity in the United States: 2010 Census and 2020 Census. Accessed September 23, 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/race-and-ethnicity-in-the-united-state-2010-and-2020-census.html

- Tsai J, Homa DM, Gentzke AS, et al. Exposure to Secondhand Smoke Among Nonsmokers — United States, 1988–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(48);1342–1346.

- Pizacani BA, Maher JE, Rohde K, Drach L, Stark MJ. Implementation of a smoke-free policy in subsidized multiunit housing: effects on smoking cessation and secondhand smoke exposure. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(9):1027–1034.

- Hafez AY, Gonzalez M, Kulik MC, Vijayaraghavan M, Glantz SA. Uneven access to smoke-free laws and policies and its effect on health equity in the United States: 2000–2019. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(11):1568–1575.

- Gonzalez M, Sanders-Jackson A, Song AV, Cheng K, Glantz SA. Strong smoke-free law coverage in the United States by race/ethnicity: 2000–2009. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):e62–e66.