Transmission of Parasitic Diseases

Pets can carry parasites and pass parasites to people. Proper handwashing can greatly reduce risk.

A zoonotic disease is a disease spread between animals and people. Zoonotic diseases can be caused by viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi. Some of these diseases are very common. For zoonotic diseases that are caused by parasites, the types of symptoms and signs can be different depending on the parasite and the person. Sometimes people with zoonotic infections can be very sick but some people have no symptoms and do not ever get sick. Other people may have symptoms such as diarrhea, muscle aches, and fever.

Foods can be the source for some zoonotic infection when animals such as cows and pigs are infected with parasites such as Cryptosporidium or Trichinella. People can acquire cryptosporidiosis if they accidentally swallow food or water that is contaminated by stool from infected animals. For example, this can happen when orchards or water sources are near cow pastures and people consume the fruit without proper washing or drink untreated water. People can acquire trichinellosis by ingesting undercooked or raw meat from bear, boar, or domestic pigs that are infected with the Trichinella parasite.

Pets can carry and pass parasites to people.

Some dog and cat parasites can infect people. Young animals, such as puppies and kittens, are more likely to be infected with roundworms and hookworms.

Wild animals can also be infected with parasites that can infect people. For example, people can be infected by the raccoon parasite Baylisascaris if they accidentally swallow soil that is contaminated with infected raccoon feces.

Regular veterinary care will protect your pet and your family.

There are simple steps you can take to protect yourself and your family from zoonotic diseases caused by parasites.

- Make sure your pet is under a veterinarian’s care to help protect your pet and your family from possible parasite infections.

- Practice the four Ps: Pick up Pet Poop Promptly, and dispose of properly. Be sure to wash your hands after handling pet waste.

- Wash your hands frequently, especially after touching animals, and avoid contact with animal feces.

- Follow proper food-handling procedures to reduce the risk of transmission from contaminated food.

- For people with weakened immune systems, be especially careful of contact with animals that could transmit these infections.

Related Links

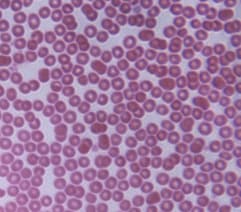

Some parasites can be bloodborne. This means

- the parasite can be found in the bloodstream of infected people; and

- the parasite might be spread to other people through exposure to an infected person’s blood (for example, by blood transfusion or by sharing needles or syringes contaminated with blood).

Examples of parasitic diseases that can be bloodborne include African trypanosomiasis, babesiosis, Chagas disease, leishmaniasis, malaria, and toxoplasmosis. In nature, many bloodborne parasites are spread by insects (vectors), so they are also referred to as vector-borne diseases. Toxoplasma gondii is not transmitted by an insect (vector).

In the United States, the risk for vector-borne transmission is very low for these parasites except for some Babesia species.

Microscopic red blood cells

Blood Transfusions

Many factors affect whether parasites that can be found in the bloodstream might be spread by blood transfusion. Examples of some of the factors include

- how much of the parasite’s life cycle is spent in the blood;

- how many parasites might be found in the blood (in other words, the concentration or level of the parasite);

- how long the parasite stays in the body, in treated and untreated people; and

- how the parasite affects people. For example, if infected people feel sick, they might not want to donate blood or they might be deferred (turned away).

Some parasites spend most or all of their life cycle in the bloodstream, such as Babesia and Plasmodium species. Parasites, such as Trypanosoma cruzi, might be found in the blood early in an infection (the acute phase) and then at much lower levels later (the chronic phase of infection). Other parasites only migrate (travel) through the blood to get to another part of the body.

There may be cases of transfusion-transmitted parasites that go undetected and unreported, but the risk for infection is very low compared with the number of blood transfusions. In the United States since 1980, there have been published reports of cases of transfusion-associated babesiosis (>150), malaria (~50), and Chagas disease (~5). Since 1965, there have been published reports of transfusion-associated toxoplasmosis (~4).

Blood Donor Screening

Potential blood donors are asked if they have had babesiosis or Chagas disease. If the answer is “yes,” the person is deferred from donating blood.

Potential blood donors are also asked about their recent international travel. People who traveled to an are where malaria transmission occurs are deferred from donating blood for 1 year after their return to the United States. Former residents of areas where malaria transmission occurs will be deferred for 3 years. People diagnosed with malaria cannot donate blood for 3 years after treatment, during which time they must have remained free of symptoms of malaria.

Donated blood is tested for a number of infectious agents. Currently, most of the U.S. blood supply is screened for Trypanosoma cruzi (the parasite that causes Chagas disease). If the results are positive, the blood center will try to notify the donor. People who test positive should consult a health care provider. Health care providers may contact CDC for confirmatory testing and management information, including treatment.

Numerous parasites can be transmitted by food including many protozoa and helminths. In the United States, the most common foodborne parasites are protozoa such as Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia intestinalis, Cyclospora cayetanensis, and Toxoplasma gondii; roundworms such as Trichinella spp. and Anisakis spp.; and tapeworms such as Diphyllobothrium spp. and Taenia spp.

Many of these organisms can also be transmitted by water, soil, or person-to-person contact. Occasionally in the U.S., but often in developing countries, a wide variety of helminthic roundworms, tapeworms, and flukes are transmitted in foods such as

- undercooked fish, crabs, and mollusks;

- undercooked meat;

- raw aquatic plants, such as watercress; and

- raw vegetables that have been contaminated by human or animal feces.

Some foods are contaminated by food service workers who practice poor hygiene or who work in unsanitary facilities.

Symptoms of foodborne parasitic infections vary greatly depending on the type of parasite. Protozoa such as Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia intestinalis, and Cyclospora cayetanensis most commonly cause diarrhea and other gastrointestinal symptoms. Helminthic infections can cause abdominal pain, diarrhea, muscle pain, cough, skin lesions, malnutrition, weight loss, neurological and many other symptoms depending on the particular organism and burden of infection. Treatment is available for most of the foodborne parasitic organisms.

Related Links

Triatomine bugs are the vectors for Chagas disease.

Credit: CDC

An insect that transmits a disease is known as a vector, and the disease is referred to as a vector-borne disease. Insects can act as mechanical vectors, meaning that the insect can carry an organism but the insect is not essential to the organism’s life cycle, such as when house flies carry organisms on the outside of their bodies that cause diarrhea in people. Insects can also serve as obligatory hosts where the disease-causing organism must undergo development before being transmitted (as in the case with malaria parasites).

Vector-borne transmission of disease can take place when the parasite enters the host through the saliva of the insect during a blood meal (for example, malaria), or from parasites in the feces of the insect that defecates immediately after a blood meal (for example, Chagas disease). Parasites transmitted by insects often circulate in the blood of the host, with the parasite residing in and damaging organs or other parts of the body.

|

Disease* |

Parasite |

Insect (vector) |

| African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) | Trypanosoma brucei gambiense, Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense | Tsetse flies |

| Babesiosis | Babesia microti and other species | Babesia microti: Ixodes (hard-bodied) ticks |

| Chagas disease | Trypanosoma cruzi | Triatomine (“kissing”) bugs |

| Leishmaniasis | Leishmania species | Phlebotomine sand flies |

| Malaria | Plasmodium species | Anopheles mosquitoes |

* These diseases are listed in alphabetical order.

In developing countries where insect control is less common, the frequency of diseases is usually greater than in areas with the resources to effectively reduce the populations of disease vector insects. In the United States, the risk for vector-borne transmission is very low for these parasites except for some Babesia species.

It is important to remember that while some species of insects are capable of transmitting disease, the majority of insects are beneficial to people and the environment.

Parasites can live in natural water sources. When outdoors, treat your water before drinking it to avoid getting sick.

Water is an essential resource for life. Water is used by everyone, every day. Not only do all people need drinking water to survive, but water plays an important role in almost every aspect of our lives – from recreation to manufacturing computers to performing medical procedures. When water becomes contaminated by parasites, however, it can cause a variety of illnesses.

Globally, contaminated water is a serious problem that can cause severe pain, disability and even death. Common global water-related diseases caused by parasites include Guinea worm, schistosomiasis, amebiasis, cryptosporidiosis (Crypto), and giardiasis. People become infected with these diseases when they swallow or have contact with water that has been contaminated by certain parasites. For example, individuals drinking water contaminated with fecal matter containing the ameba Entamoeba histolytica can get amebic dysentery (amebiasis). An individual can get Guinea worm disease when they drink water that contains the parasite Dracunculus medinensis. If an infected person with an open Guinea worm wound enters a pond or well used for drinking water, they can spread the parasite into the water and continue the cycle of contamination and infection. Schistosomiasis can be spread when people swim in or have contact with freshwater lakes that are contaminated with Schistosoma parasites.

Americans traveling abroad should take the necessary precautions to protect themselves from waterborne illness if they plan on being in countries with unsafe drinking water or recreational water. Individuals spending time in the wilderness should also follow the appropriate steps to ensure the safety of their water.

Follow the 6 Steps for Healthy Swimming to avoid recreational water illnesses (RWIs).

Parasites are also a cause of waterborne disease in the United States. Both recreational water (water used for swimming and other activities) and drinking water can become contaminated with parasites and cause illness. Recreational water illnesses (RWIs) are diseases that are spread by swallowing, breathing, or having contact with contaminated water from swimming pools, hot tubs, lakes, rivers, or the ocean.

The most commonly reported RWI is diarrhea caused by parasites, such as Cryptosporidium and Giardia intestinalis. Giardia intestinalis is also a common parasite found in drinking water. Both Cryptosporidium and Giardia intestinalis are found in the fecal matter of an infected person or animal. These parasites can be spread when someone swallows water that has been contaminated with fecal matter from an infected person or animal. Individuals with compromised immune systems who come into contact with these parasites can also be at greater risk for serious illness.

Proper sanitation and hygiene are also essential to preventing waterborne illness. Globally, CDC works to provide access to clean and safe water through a variety of programs and projects. In the United States, CDC educates the public on how to develop healthy swimming habits and protect their private well water from parasites.

Related Links

- CDC’s Healthy Water website

- CDC Global WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) Programs and Projects page

- Drinking Water: Camping, Travel, and Hiking

- Recreational Water Illness (RWI)

- Water Disinfection for Travelers

- Water-related Diseases, Contaminants, and Injuries

- Be Healthy. Think Healthy. Swim Healthy.

- Safe Water for the Community: A Guide for Establishing a Community-Based Safe Water System Program

- Safe Water Systems For the Developing World: A Handbook for Implementing Household-Based Water Treatment and Safe Storage Projects