Key points

- People and animals are getting sick from harmful algal blooms (HABs) across the U.S.

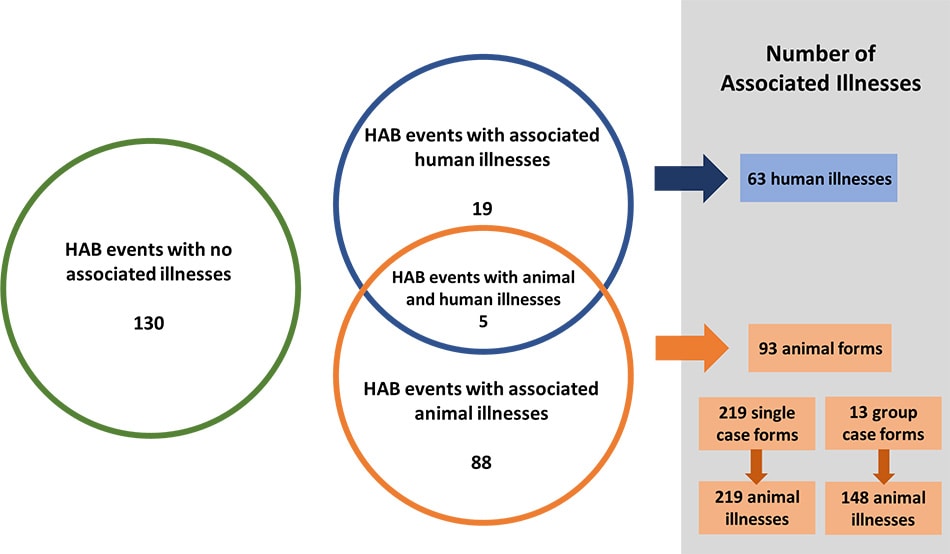

- Fourteen states voluntarily reported 242 HAB events, including 63 human cases of illness and 367 animal cases of illness.

- For both human and animal illnesses, gastrointestinal and generalized signs and symptoms were most commonly reported.

Background

Harmful algal blooms (HABs) that result from the rapid growth of algae or cyanobacteria (sometimes referred to as blue-green algae) in natural waterbodies can harm people, animals, or the environment. HAB events of public health concern are primarily caused by microalgae called diatoms and dinoflagellates, cyanobacteria, and the toxins they can produce. HAB events can be intensified by factors such as nutrient pollution and warmer water temperature and can have both public health and economic impacts.

HABs are a One Health issue—they affect the health of people, animals, and our shared environment. One Health is a collaborative and multi-sectoral approach that involves engagement across disciplines including public health, animal health, and environmental health. Using a One Health approach, CDC collects data about HAB events and associated human or animal illnesses through the One Health Harmful Algal Bloom System (OHHABS) to inform public health prevention efforts.

Within the context of OHHABS, the term HAB event may describe the identification of a bloom or the detection of HAB toxins in water or food (i.e., absent a visual bloom). Human illnesses are reported individually. Animal illnesses are reported as single cases of illness or in groups, such as flocks of birds. The reporting system can link HAB event data with human or animal illness data and uses standard definitions to classify HAB events as suspected or confirmed and human or animal illness as suspected, probable, or confirmed.

OHHABS is available for voluntary reporting by public health agencies and their designated environmental health or animal health partners in the United States, District of Columbia, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Marshall Islands, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Puerto Rico, and U.S. Virgin Islands. Public health agencies use standard forms to report HAB events, human cases of illness, and animal cases of illness to OHHABS. Public health agencies do not need to submit all three types of forms to participate.

Data collected for HAB events include general information (e.g., observation date), geographic information, water body characteristics (e.g., salinity), observational characteristics (e.g., watercolor, scum), and laboratory testing. Data collected for cases of illness include general demographic characteristics, exposure information, signs and symptoms, medical care, and health outcomes. OHHABS is a dynamic reporting system and therefore data within individual reports and across time periods are subject to change over time.

Methods

This summary describes data from OHHABS for January 1, 2019–December 31, 2019. Reports were received by January 8, 2021, and reviewed by CDC using standardized data quality checks. The final dataset was downloaded on April 14, 2021. CDC used SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute) to conduct descriptive analyses to characterize HAB events and associated human or animal cases of illness. HAB events were classified by public health agencies as suspected or confirmed and cases of illness as suspected, probable, or confirmed.

Findings

During 2019, 242 HAB events were reported by 14 state jurisdictions: Alaska, California, Connecticut, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Washington, and Wisconsin (Figure 1). These HAB events resulted in 63 human cases of illness and 367 animal cases of illness. Thirteen groups of animals were reported, ranging in size from 2-52 individuals. (Figure 2)

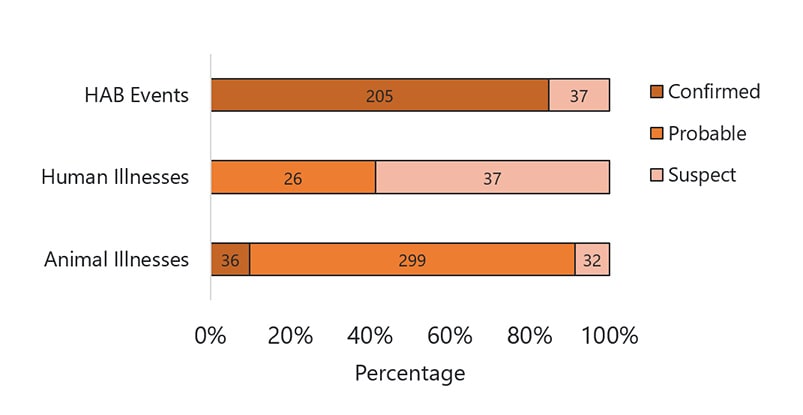

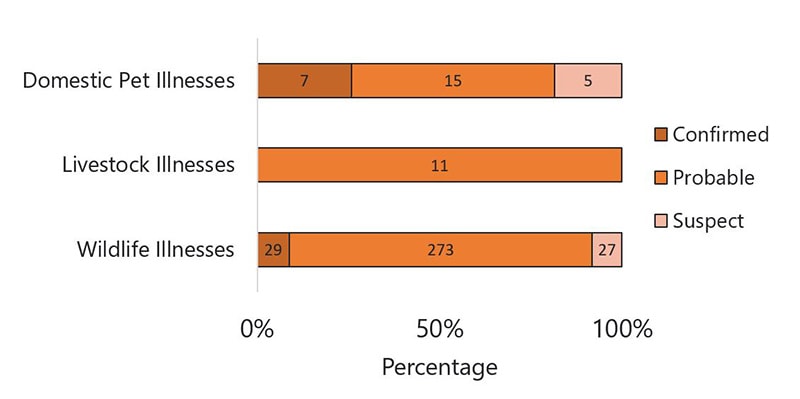

Reported HAB events occurred predominantly in summer months, peaking in August (61; 25%) (Figure 3) and were most often classified as confirmed (85%) (Figure 3). Animal cases of illness occurred primarily in June and July (58%) and human cases of illness in July and August (73%). Case classification differed between human and animal cases of illness; the majority (37; 59%) of human cases of illness were classified as suspected and 299 (81%) animal cases of illness as probable (Figure 4). No human cases of illness were classified as confirmed.

Data

Overview

Figure 1: 14 states reported to OHHABS for 2019

Figure 2: 242 HAB events resulted in 63 human illnesses and 367 animal illnesses in 2019

Figure 3: Most reported HAB events and illnesses occurred during the summer and early fall in 2019

Figure 4: In 2019, over 80% of HAB events were classified as confirmed, 59% of human illnesses as suspected, and 81% of animal illnesses as probable

| Confirmed | Probable | Suspect | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent | |

| Animal Illnesses | 36 | 10% | 299 | 81% | 32 | 9% | 367 | 100% |

| Human Illnesses | 0 | 0% | 26 | 41% | 37 | 59% | 63 | 100% |

| HAB Events | 205 | 85% | 0 | 0% | 37 | 15% | 242 | 100% |

HAB Events

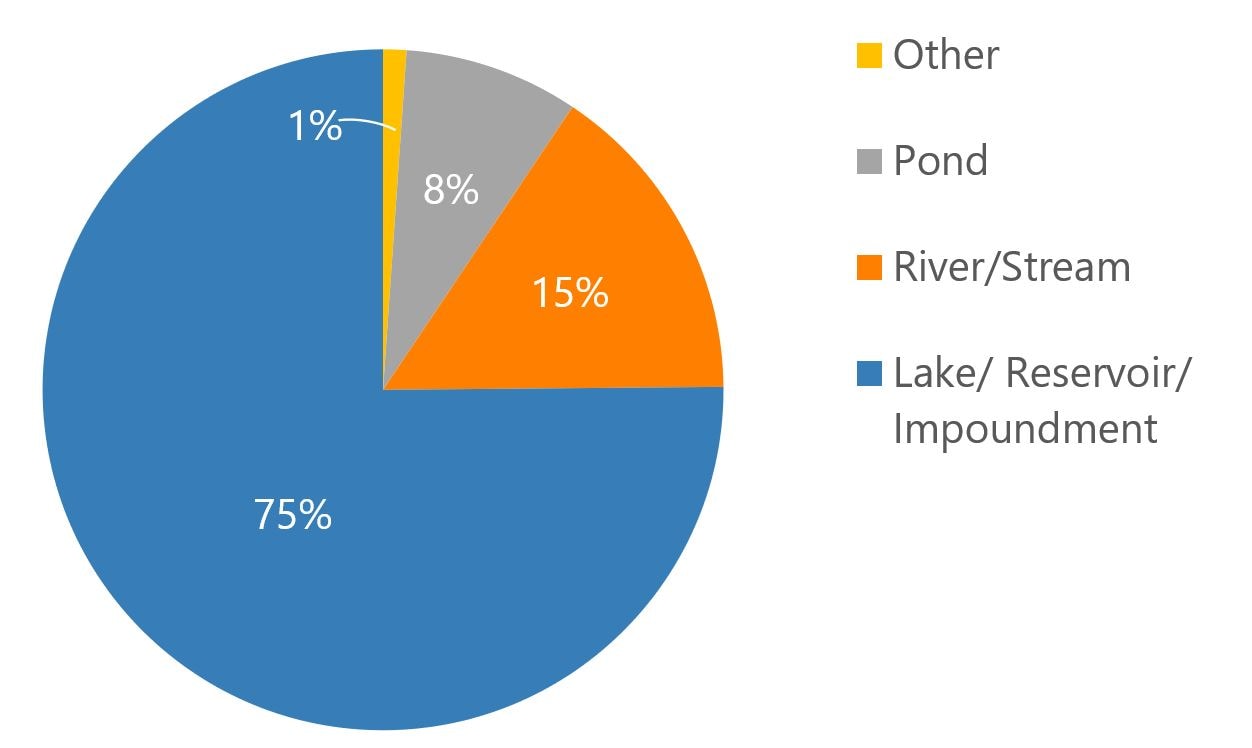

Most (181; 75%) of the 242 HAB events occurred in fresh water (Figure 5a), primarily in lakes and reservoirs (75%) (Figure 5b). Within this freshwater HAB event subset, observers most frequently noted green water color (36%), however, one or more observations of clear water were reported during 13% of these HAB events. (Figure 6). Scum was observed in 71 of 144 (49%) freshwater HAB events that included information on presence or absence.

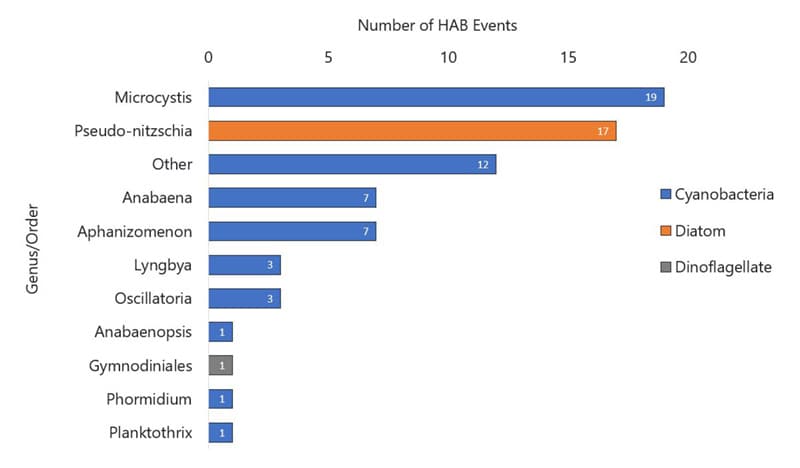

Environmental testing for algal toxins or species was conducted for 213 HAB events (88%), with the most frequently reported reasons being monitoring (75%) and citizen complaints (16%) (Figure 7). Toxins were detected in 129 of all HAB events (53%) (Figure 8), all of which were freshwater HAB events. Toxin testing primarily identified microcystins (120; 93%) (Figure 9a); multiple toxins were reported for 18 of HAB events. Microcystis was identified in 19 of 34 of HAB events with genus data available (Figure 9b).

Figure 5a: Most of the 242 HAB events from 2019 occurred in fresh water (n=181)

Figure 5b: Most freshwater HAB events from 2019 were in lakes, reservoirs, or impoundments (n=181)

| Type | Percent |

|---|---|

| Lake/Reservoir/Impoundment | 75% |

| River/Stream | 15% |

| Pond | 8% |

| Other | 1% |

Figure 6: Freshwater HAB events (n=181) primarily included observations of green or blue-green water color (n=181)

Figure 7: In 2019, environmental testing that occurred for 88% of HAB events was primarily due to water quality monitoring (n=213)

Figure 8: Environmental testing identified toxins in 53% of 2019 HAB events (n=242)

Figure 9a. Microcystins were the most commonly identified toxins during environmental testing, detected in 120 of 129 HAB events (93%)

Figure 9b. Microcystis was the most commonly identified cyanobacterial genus during environmental testing, detected in 19 of 34 HAB events (56%)

| Cyanobacteria Genus | Number of HAB Events |

|---|---|

| Microcystis | 19 |

| Other | 12 |

| Anabaena | 7 |

| Aphanizomenon | 7 |

| Lyngbya | 3 |

| Oscillatoria | 3 |

| Anabaenopsis | 1 |

| Phormidium | 1 |

| Planktothrix | 1 |

| Diatom Genus . | Number of HAB Events |

|---|---|

| Pseudo-nitzschia | 17 |

| Dinoflagellate Order | Number of HAB Events |

|---|---|

| Gymnodiniales | 1 |

Human Illnesses

Of the 63 human cases of illness reported to OHHABS for 2019, 44% were under the age of 18 (Figure 10) and 57% were female. Persons who became ill were exposed to HABs predominately at public outdoor areas or parks (85%) and most (65%) experienced single, or one-time, exposures. Nearly all (98%) attributed water as a source of exposure. Persons sought care in 51 (81%) instances; over half (65%) called a poison control center, and 13% of illnesses resulted in an emergency department visit. No deaths were reported. (Table 1)

Numerous signs and symptoms were reported; gastrointestinal and generalized signs or symptoms were documented for 67% of persons (Figure 11). Overall, diarrhea (46%) and headache (38%) were most commonly reported (Table 2). Median time to illness onset and illness duration were both 24 hours; however, 62% of ill persons still exhibited signs or symptoms at the time of interview (Table 1). A single case of foodborne illness followed ingestion of self-harvested clams and resulted in paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP).

Figure 10: Over 40% of reported human illnesses during 2019 were in people under the age of 18

Figure 11: Gastrointestinal and generalized were the most frequently reported types of signs and symptoms for persons who became ill during 2019

Table 1. 81% of ill persons sought care from at least one source, OHHABS, 2019

| Health-seeking Behavior | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Any health-seeking behavior | 51 (81) |

| Call to a poison control center | 41 (65) |

| Visit to healthcare provider | 11 (17) |

| Visit to emergency department | 8 (13) |

| Received first aid care | 2 (3) |

| Symptoms at time of case interview | 39 (62) |

Table 2. Diarrhea (46%) and headache (38%) were the most commonly reported signs and symptoms of human illness (n=63), OHHABS, 2019

| Classification | Symptom | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal | 42 (67) | |

| Abdominal cramps | 5 (8) | |

| Abdominal pain (tenderness) | 9 (14) | |

| Diarrhea | 29 (46) | |

| Gastroenteritis (nonspecific) | 1 (2) | |

| Nausea | 11 (17) | |

| Vomiting | 17 (27) | |

| Generalized | 42 (67) | |

| Anorexia (loss of appetite) | 8 (13) | |

| Body ache | 2 (3) | |

| Faintness (lightheadedness) | 1 (2) | |

| Fatigue | 13 (21) | |

| Fever | 17 (27) | |

| Flu-like symptoms | 3 (5) | |

| Headache | 24 (38) | |

| Hot flash | 1 (2) | |

| Lethargy (lack of energy, tiredness) | 2 (3) | |

| Malaise (general discomfort) | 3 (5) | |

| Pain (general) | 1 (2) | |

| Sweating | 1 (2) | |

| Dermatologic | 15 (24) | |

| Bullous skin lesions (fluid filled blisters) | 1 (2) | |

| Irritated skin | 1 (2) | |

| Rash | 13 (21) | |

| Skin blisters | 1 (2) | |

| Skin burning/pain | 1 (2) | |

| Sores | 1 (2) | |

| Ear, Nose, Throat | 15 (24) | |

| Dysphasia (difficulty swallowing) | 1 (2) | |

| Ears, ache or pain | 3 (5) | |

| Nasal inflammation | 1 (2) | |

| Nasal, congestion (rhinitis) | 2 (3) | |

| Nasal, coryza (runny nose) | 1 (2) | |

| Throat pain | 1 (2) | |

| Throat, irritation | 7 (11) | |

| Throat, sore | 5 (8) | |

| Cardiopulmonary | 11 (17) | |

| Chest tightness | 3 (5) | |

| Cough | 6 (10) | |

| Difficulty Breathing | 1 (2) | |

| Hemoptysis (coughing up blood) | 1 (2) | |

| Shortness of breath | 3 (5) | |

| Tachycardia (rapid heartbeat) | 1 (2) | |

| Wheezing | 1 (2) | |

| Neurologic | 8 (13) | |

| Confusion | 2 (3) | |

| Dizziness | 2 (3) | |

| Neurological symptoms (nonspecific) | 1 (2) | |

| Paresthesia (tingling sensation) | 2 (3) | |

| Speech difficulty | 1 (2) | |

| Tremors (trembling, shakes) | 1 (2) | |

| Weakness | 4 (6) | |

| Genitourinary | 4 (6) | |

| Dark urine | 1 (2) | |

| Hematuria (blood in urine) | 1 (2) | |

| Urinary tract infection | 2 (3) | |

| Musculoskeletal | 4 (6) | |

| Arthralgia (joint pain) | 1 (2) | |

| Difficulty walking | 2 (3) | |

| Muscle fatigue | 1 (2) | |

| Muscle pain | 2 (3) | |

| Ophthalmologic | 3 (5) | |

| Eye symptoms (nonspecific) | 2 (3) | |

| Eyes, watery | 1 (2) | |

| Other | 3 (5) | |

| Anaphylaxis (allergic reaction) | 1 (2) | |

| Other | 6 (10) |

Animal Illnesses

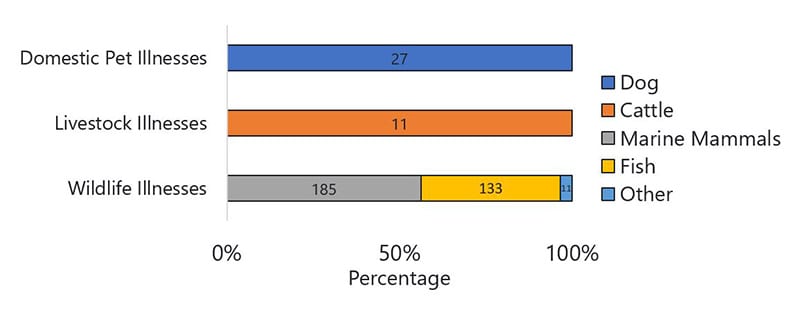

Of the at least 367 animal cases of illness reported to OHHABS for 2019, most were classified as probable (81%), regardless of animal category (Figure 12). Among 27 domestic pets, 11 livestock, and 329 wildlife, the most common animals affected were dogs (100%), cattle (100%), and marine mammals (i.e., sea lions, dolphins, seals, and one whale; 56%) (Figure 13). More than half (61%) of animals were exposed at parks or public outdoor areas. Veterinary care was provided to 69 (19%) animals.

Data describing signs of illness were available for 36 animals. Gastrointestinal and generalized signs were most frequently reported overall (47% and 42%, respectively) (Figure 14). Individually, vomiting (33%) was most commonly reported (Table 3). Median time to illness onset was 1 hour (.02-24) for the 13 animals with available information and median duration was 5 hours (.03-120) for 11 animals with available information. In total, 207 (56%) of the animals died.

Figure 12: Most animal illnesses reported for 2019 were classified as probable

| Diatom Genus . | Number of HAB Events |

|---|---|

| Pseudo-nitzschia | 17 |

Figure 13: Most animal illnesses reported for 2019 affected marine mammals or fish

| Reported Animal Illnesses | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Individual Number of Animals Affected | 367 | 100% |

| Domestic Pet | 27 | 7% |

| Dog | 27 | 100% |

| Livestock | 11 | 3% |

| Cattle | 11 | 100% |

| Wildlife | 329 | 90% |

| Bird | 8 | 2% |

| Fish | 133 | 40% |

| Marine mammal | 185 | 56% |

| Reptile | 3 | 1% |

Figure 14: Gastrointestinal and generalized signs were most frequently reported signs for animal illnesses during 2019

Table 3: Vomiting (33%) was the most commonly observed sign in reported animal illnesses (n=36), OHHABS, 2019

| Classification | Symptom | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal | 17 (47) | |

| Bloody diarrhea | 3 (8) | |

| Diarrhea | 4 (11) | |

| Liver failure | 1 (3) | |

| Vomit with bile | 3 (8) | |

| Vomiting | 12 (33) | |

| Generalized | 15 (42) | |

| Anorexia (loss of appetite) | 7 (19) | |

| Anxiety | 3 (8) | |

| Collapse (unable to stand) | 4 (11) | |

| Drooling/Salivation | 8 (22) | |

| Fever | 3 (8) | |

| Foaming at the mouth | 1 (3) | |

| Lethargy | 10 (28) | |

| Muscle tremors | 2 (6) | |

| Weakness | 2 (6) | |

| Whining or abnormal vocalization | 1 (3) | |

| Neurologic | 14 (39) | |

| Ataxia (stumbling, loss of balance) | 6 (17) | |

| Behavior change | 6 (17) | |

| Coma (non-responsive to stimuli) | 1 (3) | |

| Paralysis | 1 (3) | |

| Seizure/Convulsions | 8 (22) | |

| Ear, Nose, Throat | 10 (28) | |

| Deafness | 10 (28) | |

| Cardiopulmonary | 10 (28) | |

| Cough | 1 (3) | |

| Labored breathing | 4 (11) | |

| Panting | 2 (6) | |

| Rapid breathing | 3 (8) | |

| Wheezing | 1 (3) | |

| Other | 7 (19) | |

| Other | 7 (19) | |

| Dermatologic | 1 (3) | |

| Rash | 1 (3) | |

| Redness/Swelling | 1 (3) | |

| Genitourinary | 1 (3) | |

| Dark urine | 1 (3) | |

| Ophthalmologic | 1 (3) | |

| Eye discharge | 1 (3) |

Limitations

Data reported in OHHABS for 2019 are not representative of HAB event or illness occurrence in the United States because reporting is voluntary and not all states are currently reporting to this system. Additionally, states may not report information for all HAB events or illnesses due to variability in surveillance capacity, surveillance program scope, or limitations to the environmental or health data available for HAB events. Summarized data therefore underrepresent the total number of HAB events and illnesses that occurred within or across states. Similarly, relative contributions of HAB events in salt water, toxins identified in fresh water, and types of illnesses (e.g., domestic pets versus wildlife species) may also be affected.

Conclusion

Fourteen states reported to OHHABS for 2019. This represents a cumulative increase in adoption of the system by four additional states compared to 2016–2018, the first reporting period. The findings from this annual data summary indicate that HAB events and associated illnesses occur throughout the United States. HAB event and illness reporting primarily characterized environmental data, exposures, and outcomes associated with freshwater cyanobacterial blooms. Illness characteristics for both humans and animals are consistent with previous findings related to cyanobacterial blooms exposures (Backer, 2015, Roberts 2020).

Additionally, these data highlight the interconnectedness of human health, animal health, and environmental health in understanding and better characterizing HAB events and associated illnesses. Continued use of a One Health approach will improve data available to inform illness prevention.

Citations

Backer LC, Manassaram-Baptiste D, LePrell R, Bolton B. Cyanobacteria and algae blooms: Review of health and environmental data from the Harmful Algal Bloom-Related Illness Surveillance System (HABISS) 2007-2011. Toxins (Basel). 2015 Mar 27;7(4):1048-64. doi: 10.3390/toxins7041048. PMID: 25826054; PMCID: PMC4417954.

Roberts VA, Vigar M, Backer L, et al. Surveillance for Harmful Algal Bloom Events and Associated Human and Animal Illnesses — One Health Harmful Algal Bloom System, United States, 2016–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1889–1894. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6950a2

Acknowledgements

CDC would like to thank state and local waterborne disease coordinators, epidemiologists, environmental health practitioners, laboratorians, toxicologists, and animal health practitioners, as well as other partners who were involved in investigating or reporting these data to OHHABS.