Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail.

Lexicon, Definitions, and Conceptual Framework for Public Health Surveillance

Supplements

July 27, 2012 / 61(03);10-14Corresponding author: H. Irene Hall, PhD, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, CDC, MS E47, Atlanta, Georgia 30329-1902; Telephone: 404-639-4679; Fax: 404-639-2980; E-mail: ihall@cdc.gov.

Public health surveillance is essential to the practice of public health and to guide prevention and control activities and evaluate outcomes of such activities. With advances in information sciences and technology, changes in methodology, data availability and data synthesis, and expanded health information needs, the question arises whether redefining public health surveillance is needed for the 21st century. The current definition is "Public health surveillance is the ongoing, systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health data, essential to the planning, implementation and evaluation of public health practice, closely integrated with the dissemination of these data to those who need to know and linked to prevention and control (1)."

This report describes a review of this definition and considers proposed needs for health information (Box). This topic was identified by CDC leadership as one of six major concerns that must be addressed by the public health community to advance public health surveillance in the 21st century. The six topics were discussed by CDC workgroups that were convened as part of the 2009 Surveillance Consultation to advance public health surveillance to meet continuing and new challenges (2). This report is based on workgroup discussions and is intended to continue the conversations with the public health community for a shared vision for public health surveillance in the 21st century.

Changing Landscape and Health Information Needs

Health information needs reflect innovations or qualitative changes in health metrics and methodologies and changes in knowledge needs. They also have been accompanied by the development and use of new terms, an inclusion of more complex health events under the scope of surveillance activities, and new questions regarding the overlap of surveillance with other types of activities in information sciences and public health practice. The workgroup consultants proposed the data needs and reviewed related terminology to define what public health surveillance is and what it is not. The review included the purpose or intent of public health surveillance: why, in what areas, and how public health surveillance is conducted. Furthermore, the workgroup consultants reviewed relations among data collection, analysis, reporting activities, and a conceptual framework for population health assessment.

Gaps and Opportunities

The value of surveillance lies in the effective and efficient delivery of useful information. Therefore, a surveillance system must be flexible enough to adjust to expanding health information needs and to use the best technology to deliver the data when and where they are needed. Failure of public health surveillance to deliver needed information can occur when single-disease systems cannot be used to determine relations between health conditions or comorbidities (e.g., through data linkage), or when appropriate health information is not collected when a potential exists for a substantial threat but what needs to be measured is not known. Gaps in health knowledge can occur when surveillance systems are not timely, complete, easily adapted, or efficient. For example, information that is not timely can result in a missed opportunity to intervene, especially for acute events. Information that is not complete can result in failure to recognize a public health threat. Surveillance systems that are not easily adapted to changing information needs might not be able to evaluate the impact of new prevention interventions in different population subgroups. Surveillance systems that are not efficient (e.g., the delivery of needed information demands more resources than are available) will not be useful.

To address these gaps, public health surveillance can benefit from advances in information sciences and technology and the increasing availability of databases and data sources. New information technologies provide opportunities for better data compilation, analysis, and dissemination. Electronic reporting, electronic health records, standardized data exchange, and automated data processing are examples of how the practice of surveillance has changed or is likely to change in the future, as are the uses of such methods in laboratory information systems and electronic health records. New data or information sources, such as unstructured clinical data, internet data sources, media content, and environmental and climate change data provide expanded opportunities to enhance health knowledge by facilitating more detailed characterization of events of interest with respect to time, place, and person. A clear definition of public health surveillance is needed to determine whether systems that use these types of data constitute public health surveillance.

Principles of Public Health Surveillance

For the purpose of discussing the lexicon, definitions, and the conceptual framework of public health surveillance, articulating the basic principles underlying public health surveillance is useful and important. The workgroup consultants derived two basic principles from the definition of public health surveillance.

One of these basic principles relates to the purpose of public health surveillance, which is twofold: 1) to address a defined public health problem or question, and 2) to use the data to guide efforts that will protect and promote population health. A second basic principle relates to the nature of public health surveillance as an ongoing and systematic implementation of a set of processes consisting of 1) planning and system design, 2) data collection, 3) data analysis, 4) interpretation of results of analysis (i.e., generation of information), 5) dissemination and communication of information, and 6) application of information to public health programs and practice.

These principles were considered useful for framing deliberations on key public health surveillance concepts and terms and relations among data collection and use activities and placing public health surveillance activities within the larger context of population health assessment and actionable public health knowledge (i.e., knowledge for public health decision making and/or disease control and prevention).

Concepts of Public Health Surveillance

The traditional definition of public health surveillance includes a series of concepts that can be interpreted in various ways. A traditional interpretation of key concepts leads to a narrow definition of the scope of public health surveillance systems to include morbidity and mortality of diseases or specific health events. Conversely, a more expansive interpretation opens the field of public health surveillance to new areas of public health inquiry using innovative data sources, methods of data collection and analysis, and application to several public health concerns. This latter interpretation of key concepts was adopted because it was considered essential to adapt to the health information needs and the advancement of public health surveillance in the 21st century.

In this regard, selected key concepts were considered in detail. Primary among them is the ongoing systematic collection of health data. The temporal aspects of surveillance are divided into two concepts: the temporal occurrence of events and the reporting frequency of those events. The concept of "ongoing" can be interpreted to imply that all events are equally likely to be captured in the surveillance system regardless of the time in which the events occurred. This approach is often applied to disease "case" surveillance systems (e.g., the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System). Although these systems rarely capture all cases of disease, they do attempt to consistently capture a proportion of events over time. This is in contrast to an approach that captures snap shots of events in a defined period, which is repeated periodically and on an ongoing basis. Certain events occurring with some periodicity, but not in synchrony with the data collection process, would not be captured because their occurrence in a time period was not included in the data collection. This latter approach was considered to be analogous to sentinel surveillance based on location, in which certain cases would not be captured because of the geographic variation of their occurrence. The periodic data collection, regardless of whether the periodicity is regular or irregular, conforms to the concept of ongoing systematic collection.

Reporting frequency is related to the usefulness of the data to inform public health programs. Delayed reporting, whether for primary capture in the system or for interpretation of data for programs, might limit the usefulness of the data and weaken the link to prevention and control activities. Under such circumstances, the link between data collection and public health program activities might be lost; consequently, the data collection activity might not meet the purpose of public health surveillance. Nonetheless, whether the reporting frequency is determined to be adequate depends on the topic or event addressed by the surveillance system. Although rapid reporting is essential for detection and prevention of high-hazard events (e.g., lethal communicable diseases), rapid reporting might not be essential for chronic disease surveillance where time frames for interventions are longer. For different types of health events, the time scales of public health program intervention differ dramatically, and thus the effective frequency of reporting for different events differ. For this reason, the frequency of reporting was not considered a determining factor in the definition of public health surveillance.

Another important concept is health information. Many traditional public health surveillance systems address morbidity and mortality in human populations, whereby health information is directly related to human health. However, many types of information inform public health programs. These types of information include, but are not limited to, environmental exposures, occupational exposures, disease vectors and vehicles, risk behaviors, population characteristics, and health policies. For example, health policy information might be applicable to health-care reform, a topic of interest to decision makers and public health programs. Several types of health information, whether directly or indirectly related to human health, might be applicable to public health surveillance. The type of health information used does not define public health surveillance. Rather, the crux of public health surveillance is related to the key principles of applying information to a defined public health problem and its use to guide strategies that protect and promote population health.

The sources of health information in public health surveillance are similarly varied. Sources include direct ascertainment from persons in a population, from clinical or laboratory sources, or from other systems designed for a purpose other than public heath surveillance. For example, the census is conducted for many purposes and is not considered a public health surveillance system. However, the census is a source of population data used in public health surveillance systems.

The final key concept is the link to prevention and control. This concept can be broadly defined in the context of public health surveillance. The link of information to interventions in prevention and control of disease or injury is essential for a surveillance program to consider. Public health surveillance might be conducted for conditions for which no public health interventions exist (e.g., for the occurrence and outcomes related to certain congenital diseases or disorders). Nonetheless, public health surveillance for these conditions might be important to prioritize and guide research, which guide development of public health interventions for use in the future or for planning services. In addition, this type of surveillance might be important to guide interventions for other important sequelae such as co-morbidities or behavioral modifications to allow family members, health systems, and communities to better accommodate persons with certain conditions.

For these concepts and others related to the definition of public health surveillance, broad, flexible interpretations were applied. This approach was considered critical for meeting the demands on and opportunities for public health programs in the 21st century. Future needs and concerns might be ongoing issues or variations of them or new challenges. Public health surveillance will need to be innovative to meet the needs of decision makers and drive prevention and control programs of the future.

Relations Between Public Health Surveillance and Other Data Collection Activities

Public health surveillance is not defined by the system used to collect data but by the purpose of the data collection — the specific public health question that the data will be used to answer and the link to disease prevention and control. Tracking the health of the population is an essential component of effective public health practice. Data are needed for monitoring trends and patterns, identifying outbreaks, developing and evaluating interventions, setting research priorities, monitoring quality of care and patient outcomes, recognizing drug resistance to infectious disease agents, identifying underserved populations, and planning services. In some instances, data to address health concerns can be collected in a single system, particularly if a mandate for reporting is included. One example is the CDC National Electronic Disease Surveillance System, which was established to facilitate accurate, complete, and timely reporting of infectious diseases from state and local health departments. However, for many noninfectious diseases and conditions, surveillance must be broad in scope and must rely on numerous other data collection activities. Public health surveillance for noninfectious disease is often built on a framework of indicators from different data sources.

Even when surveillance is not the primary aim of the activity, data collection can still yield valuable information for surveillance purposes when the data collection adheres to some of the basic principles for surveillance. For example, health data collected for administrative purposes (e.g., Medicare and hospital discharges) cover a majority of the population and are particularly useful for monitoring trends and assessing burden of disease. Surveys can be a rich source of surveillance data when they are periodic, population based, and maintain assessment standards over time. Surveys such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, National Health Interview Survey, and the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey have provided valuable surveillance data on behaviors, biomarkers, preventive services, and risk factor and condition prevalence. Disease registries are often established for research purposes or to track adverse events, yet they can provide valuable data for surveillance purposes. For example, cancer registries can provide cancer-specific incidence data, mortality rates by geographic area, and age-adjusted rates for comparisons over time and across communities/regions. Even hospital-based registries can provide surveillance data when the population covered can be defined and estimated.

Often, data are not available on the whole population. In such situations, sentinel surveillance systems can provide sufficient information for making public health decisions or detecting trends. The main purpose of sentinel surveillance is to obtain timely information on a preventable disease, injury, or untimely death, the occurrence of which serves as an indicator that the quality of preventive or therapeutic care might need improvement. Sentinel surveillance is of value when national surveillance systems are not available, large surveys would be too costly, or condition prevalence is high and collecting data on every case would be impractical. Types of sentinel surveillance include 1) monitoring specific health events in clinical settings; 2) reporting by hospitals or networks of providers of data on specific conditions or events; and 3) localized, longitudinal cohorts, registries, and screening programs. Although data from these sources are not nationally representative, they can provide a detailed picture of disease and risk-factor trends in a geographically defined area or in a population subgroup defined by age, sex, race/ethnicity or other demographic characteristics.

Information from varied data sources can be incorporated into public health surveillance activities. Some are not strictly health data but might include climate, occupational exposures, environmental hazards, risk factors, laws and regulations, or social determinants of health. Tracking these data over time is important for understanding the context in which disease occurs and, when linked with health outcomes at the individual or population level, can provide federal, state, and local agencies important information for disease prevention, detection, and control. Another emerging source of health data for surveillance is the electronic health record (EHR). Although the technology has yet to be widely adopted and concerns about access and privacy need to be resolved, EHRs have the potential to generate entirely new data for monitoring the health of the population. What is traditionally regarded as clinical data (e.g., records from out-patient clinics, laboratories, or pharmacies) could be transformed into surveillance data at the population level. The data also could be used to establish new disease registries yielding previously unavailable population-based morbidity and disease incidence data and to track how persons move through and beyond the health-care system across the lifespan.

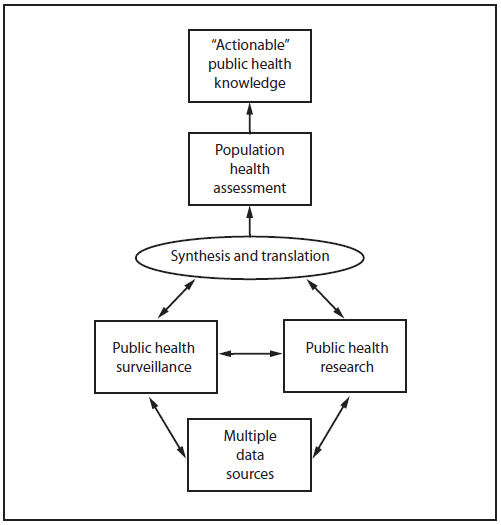

Numerous sources of data that are used for public health surveillance also are the basis for public health research (Figure 1). Surveillance and research are distinguished by the purpose of the data collection. Surveillance is used to gather data and knowledge that can be used to identify and control a health problem or improve a public health program or service, whereas the purpose of research is to generate generalizable knowledge. In some instances, public health surveillance activities can serve as a source of case finding for further research or can suggest hypotheses or areas of interest for more in-depth research. Data collection activities originally designed for research can serve as vital sources of surveillance data. Although different in purpose, public health research and public health surveillance are closely linked in public health practice and rely on many of the same data sources and methods.

This review considered the purpose of public health surveillance; relations among data collection, analysis, reporting activities; and a conceptual framework for population health assessment. The workgroup conclusion is that the existing definition of public health surveillance remains relevant, applicable, and flexible and does not need to be changed.

References

- Thacker SB, Berkelman RL. History of public health surveillance. In: Public Health Surveillance, Halperin W, Baker EL (Eds.): New York; Van Norstrand Reinhold, 1992.

- CDC. Introduction. In: Challenges and opportunities in public health surveillance: a CDC Perspective. MMWR 2012;61(Suppl; July 27, 2012):1-2.

|

BOX. Health information needs for the 21st century |

|

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

|

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

**Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.