|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

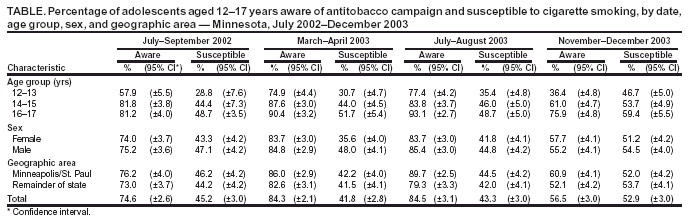

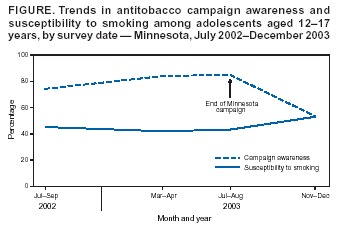

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Effect of Ending an Antitobacco Youth Campaign on Adolescent Susceptibility to Cigarette Smoking --- Minnesota, 2002--2003The majority of persons who become regular cigarette smokers begin smoking during adolescence. Comprehensive state antitobacco programs, especially those with strong advertising (i.e., paid media) campaigns, have contributed to the substantial decline in adolescent smoking since 1997 (1,2). In Minnesota, annual funding for tobacco-control programs was reduced from $23.7 million to $4.6 million in July 2003, ending the Target Market (TM) campaign directed at youths since 2000. To assess the effects of cutting the state's tobacco-control funding, during November--December 2003, the University of Miami School of Medicine surveyed Minnesota adolescents aged 12--17 years to determine their awareness of the TM campaign and their susceptibility to smoking. These data were compared with results from previous surveys. This report summarizes the results of that analysis, which indicated that the percentage of adolescents who were aware of the TM campaign declined from 84.5% during July--August 2003 to 56.5% during November--December 2003, and the percentage of adolescents susceptible to cigarette smoking increased from 43.3% to 52.9%. These findings underscore the need to maintain adequate funding of state antitobacco programs to prevent tobacco use among youths. Begun in 2000, the Minnesota TM campaign was organized around three components: a paid advertising campaign, a youth organization, and a website targeted to youth. Each component was branded with the TM logo. Data from four cross-sectional telephone surveys of Minnesota youths aged 12--17 years were used to measure the target audience's awareness of the campaign and the impact of the campaign on susceptibility to smoking. The four surveys were conducted during July--September 2002, March--April 2003, July--August 2003, and November--December 2003. A $10 department store gift card was used as an incentive to participate, and parental permission was required. Response rates for the four surveys ranged from 73.2% to 76.1%, and sample sizes ranged from 1,079 to 1,150. The demographic distribution of each sample, according to 2000 U.S. census data, was similar to that of the adolescent population in Minnesota by age group, sex, race/ethnicity, and geographic region (i.e., Minneapolis/St. Paul metropolitan area versus the rest of the state) (3). Confirmed campaign awareness was defined as awareness of the TM brand logo, as indicated by responses to the statement, "When you see the capital letters `TM' inside of a circle, tell me what you think of." To confirm brand awareness, survey participants had to provide responses that were specific to the TM brand message (e.g., linking specific campaign components to campaign objectives, the brand logo with a major message theme, or acknowledging TM as an organized movement). Overly general responses, such as "Don't smoke," were not counted as confirmed awareness. To determine susceptibility to cigarette smoking (4,5), participants were asked to respond to the statement, "You will smoke a cigarette in the next year." Susceptibility was defined as any response other than "strongly disagree." The same statements and response categories for confirmed campaign awareness and susceptibility to smoking were used for all four surveys. Findings from surveys conducted during July--September 2002 (2 years after the campaign began), March--April 2003, and July--August 2003 indicated an increase in confirmed campaign awareness from 74.6% to 84.5%, with a plateau observed between the second and third surveys. The youth campaign was ended in July 2003, and a statistically significant decline to 56.5% occurred in confirmed awareness between the surveys conducted during July--August 2003 and November--December 2003 (Figure). Similar patterns for campaign awareness were observed by age group, sex, and geographic area (Table). In addition, between the July--August 2003 and November--December 2003 surveys, a corresponding statistically significant increase in susceptibility to smoking, from 43.3% to 52.9%, occurred among Minnesota adolescents (Figure). Susceptibility to smoking increased in all age groups, both sexes, and by geographic area. Reported by: D Sly, PhD, K Arheart, EdD, N Dietz, PhD, Univ of Miami School of Medicine, Florida. C Borgen, MBA, Minnesota Dept of Health. E Trapido, SciD, Div of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute. D Nelson, MD, J McKenna, MS, Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC. Editorial Note:The findings in this report demonstrate the impact on awareness of elimination of a Minnesota youth antitobacco campaign 6 months after that campaign ended and suggest that state cutbacks in antitobacco campaigns might increase the susceptibility of youths to smoking, which is a key predictor of adolescent tobacco use (4,5). These findings are consistent with data from a previous study in Massachusetts that documented an increase in illegal tobacco sales to minors after funding cuts to that state's antitobacco program (6). These findings are of particular concern in states where antitobacco efforts have been cut substantially. For example, programs in Massachusetts and Florida included paid media campaigns and substantial youth components before funding declined 92% and 99%, respectively, from peak levels (7). The prevalence of smoking among youths has declined most rapidly in states that have used the most extensive paid media campaigns in combination with other antitobacco activities (8). For example, after a comprehensive program with an extensive paid media campaign was initiated in Florida, smoking prevalence among middle school students declined 40% in 2 years (8). In 1998, the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) was accepted by states and the tobacco industry. MSA provided more than $200 billion to states over 25 years (7). Proponents of MSA, including governors and other state leaders, supported using these funds for antitobacco programs (7). However, at least 20 states and the District of Columbia have issued or plan to issue bonds backed by MSA payments, allowing them to receive their MSA funds in advance, often to help reduce state revenue shortfalls (7). As a result, MSA funds in multiple states might not be available to sustain effective antitobacco efforts. The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations. First, all data are self-reported and might be subject to recall bias. Second, participants' campaign awareness was assessed on the basis of their TM brand awareness; certain respondents might not have recognized the logo yet still might have been aware of the campaign and vice versa. Third, susceptibility to smoking might be caused by factors other than cuts in antitobacco programs, such as increased marketing of tobacco products. Finally, not all adolescents categorized as having increased susceptibility become regular cigarette smokers. However, in prospective studies, this categorization has been found to be strongly and independently associated with increased likelihood of regular cigarette smoking (4,5). The components of successful state youth antitobacco programs are based on substantial research; such programs include countermarketing, increased tobacco excise taxes, comprehensive school-based education programs, enforcement of tobacco-control laws, and ongoing surveillance and evaluation (1,9). Paid media campaigns are critical to countermarketing (9). When combined with other interventions, such campaigns are strongly recommended by the Task Force on Community Preventive Services to prevent initiation of tobacco use by youth (1). In Minnesota, paid advertisements consistently have accounted for >90% of total campaign awareness (3). Because tobacco use remains the leading preventable cause of death in the United States, efforts to prevent smoking initiation among youths can have a profound impact on public health. While cutbacks in state programs were occurring, the tobacco industry spent $11.2 billion in 2001 (the most recent year for which data are available), or $39 per person in the United States, on advertising and promotion expenditures (10). These tobacco industry expenditures were 17% higher than the previous year and nearly double the amount spent on marketing in 1997, the year before MSA (10). The decline in campaign awareness and increase in adolescent susceptibility in Minnesota suggest that antitobacco funding cuts could reverse the recent declines in youth tobacco use. References

Table  Return to top. Figure  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 4/15/2004 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 4/15/2004

|