|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

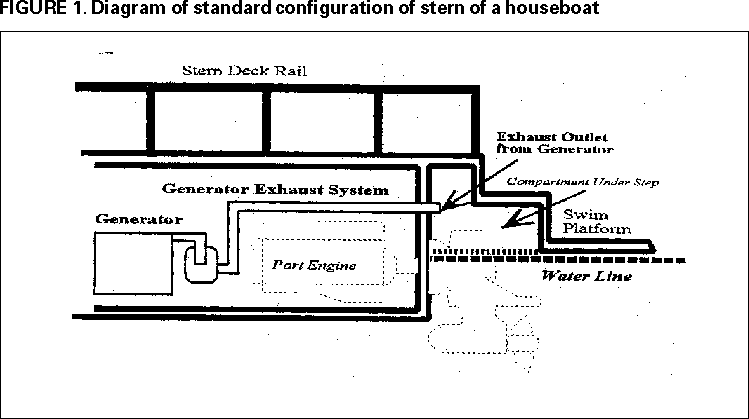

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Houseboat-Associated Carbon Monoxide Poisonings on Lake Powell --- Arizona and Utah, 2000During August 2000 at Lake Powell in the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area on the Arizona-Utah border, two brothers died of carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning as they swam near the stern of a houseboat while the onboard gasoline-powered generator was operating. As a result of these deaths, an investigation was initiated by the U.S. National Park Service (NPS) with assistance from the U.S. Department of the Interior, CDC's National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and the U.S. Coast Guard. In addition to investigating the deaths of the two brothers, the multiagency team evaluated visitor and worker boat-related CO exposures at Lake Powell. The study identified nine boat-related fatal CO poisonings since 1994 and approximately 100 nonfatal poisonings since 1990. This report describes the preliminary results of an ongoing investigation of watercraft-related CO poisonings on Lake Powell. Incident ReportsIncident 1. On August 2, 2000, two families vacationing on a houseboat on Lake Powell started the boat generator to cool the boat interior and operate the television. About 15 minutes later, two brothers (aged 8 and 11 years) swam into the airspace beneath the swim deck enclosed by the swim platform that was near water level (Figure 1) into which the exhaust of the generator was directed. Within an estimated 1--2 minutes, one boy lost consciousness and the other began to convulse before sinking underwater. The brothers' bodies were retrieved the next day. Autopsy results showed that the boys had been overcome by CO and subsequently drowned; autopsy carboxyhemoglobin (COHb) levels were 59% and 52%. Incident 2. On August 18, 1994, three teenaged boys were swimming off the stern of a houseboat similar in design to that in incident one. The houseboat generator was operating. The boys were climbing up the back of the houseboat and sliding down a rear-mounted slide into the water. After several minutes, one of the boys developed a headache and went inside the boat cabin. While in the water, another boy commented that his legs felt numb and that he was dizzy. He climbed back onto the boat and is believed to have collapsed and fallen back into the water. Approximately 1 hour later, his body was recovered from the bottom of the lake. An autopsy revealed a COHb level of 53.9%. Incidents 3, 4, and 5. During August 1998, three CO poisonings occurred on Lake Powell within the span of 12 days. All involved entry of the airspace beneath the swim deck for engine maintenance or clearing ropes from propellers, and all boats had de signs similar to those in incidents one and two. Two of the incidents resulted in fatal CO poisonings (COHb levels of 55% and 49%); the third incident involved a concessionaire employee who lost consciousness while in the water but who was retrieved and resuscitated. Review of Medical RecordsTo further examine risk factors for such incidents, the team reviewed NPS emergency medical service (EMS) transport records for 1990--2000 to characterize the circumstances and number of boat-related CO poisonings. A total of 181 records was selected based on the notation of "CO poisoning" or symptoms consistent with CO poisoning and was reviewed for case classification. Of these, 111 definite cases of boat-related CO poisonings were identified.* COHb levels have been obtained for 25 cases. Nine (8%) of the 111 CO poisonings were fatal, and five deaths occurred after the victim entered the cavity beneath the swim platform of the houseboat during operation of or immediately after deactivation of the generator or boat engines; two additional deaths occurred when the victims were overcome while standing on or swimming near a houseboat swim platform. The remaining two deaths occurred on pleasure crafts. Ages of the persons who died ranged from 8 to 66 years. Of the 111 CO poisonings, 74 (67%) occurred on houseboats and 30 (27%) occurred on pleasure crafts; seven records did not specify a boat type. Of the 74 CO-related poisonings on houseboats, 37 (50%) occurred outdoors, and half of those resulted in loss of conciousness. Environmental SamplingMaximum CO concentrations measured in the cavity beneath the stern deck on houseboats on Lake Powell ranged from 6,000--30,000 parts of CO per million parts of air (ppm) while the generators were in operation. Oxygen concentrations as low as 12% also were measured. This oxygen deficient, CO-rich environment in a confined space is lethal within seconds to minutes. In addition, environmental measurements and case reports indicated that CO concentrations on and near the swim platform can reach life-threatening concentrations (measured as high as 7200 ppm). CO tends to accumulate above the water near the platform, and CO concentrations as high as 200 ppm were measured at water level 10 feet away from the platform. Reported by: RL Baron, MD, National Park Svc Glen Canyon National Recreational Area, and Good Samaritan Regional Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona. T Radtke, Dept of the Interior, Denver Field Office. Div of Surveillance, Hazard Evaluation, and Field Studies, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, CDC. Editorial Note:CO poisoning associated with indoor exposure has long been recognized. However, the events described in this report illustrate a more rarely reported phenomenon---severe CO poisoning occurring outdoors. The outdoor poisonings at Lake Powell and those reported elsewhere (1,2; D. Lucas, Ohio Division of Watercraft, personal communication, 2000) probably represent a larger number of deaths not recognized as CO poisoning. Because symptoms of CO poisoning resemble those of other common conditions (e.g., alcohol consumption, motion sickness, heat stress, and nonspecific viral illness), poisonings often go unrecognized. In addition, associating illness with this exposure requires awareness of the problem among EMS staff, hospital emergency department personnel, and coroners. The preliminary findings of this investigation indicate that houseboats with a rear swim deck and a water-level swim platform are an imminent danger to persons who enter the air space beneath the deck or spend time near the rear deck. The presence of features (e.g., engine propellers, water slides, and swim platform) that attract occupancy of that airspace enhances the risk for severe injury and death. To prevent CO poisonings and deaths, boat manufacturers should immediately devise engineering changes to new and existing boats to prevent the collection of CO in airspaces around the stern deck. Boat manufacturers should evaluate the effectiveness of such controls. Boat owners should contact the manufacturer of their boats to determine whether effective corrective measures have been identified. State and federal agencies that issue boat registrations or that regulate lakes and/or boats in their jurisdictions should assess their legal authority to determine what actions might be taken to prevent these deaths. Workers also may be exposed to very high CO concentrations. According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the area beneath the swim deck should be designated as a confined space, and confined space entry procedures† must be implemented before an employee enters the water to service engine components beneath the deck. CO poisonings also occur inside houseboats (3); 36 of the nonfatal CO poisonings at Lake Powell occurred inside boat cabins, and eight of these were in boats on which CO detectors had been disabled because of repeated alarms. Federal, state, and local agencies and boat manufacturers should improve public awareness of the hazards of CO on houseboats to ensure that boat occupants heed such alarms and act accordingly. All boats should be equipped with CO detectors, and boat occupants should never disable alarms. The team has initiated an extensive effort to increase awareness of the problem by enlisting the help of state health departments, boat safety organizations, and other public health groups. The team also is developing plans to educate EMS and hospital emergency department staff to improve patient care through more rapid identification of CO poisoning symptoms. In August 2000, Lake Powell NPS officials initiated a public awareness program aimed at boat owners, renters, and occupants that included widespread posting and distribution of warning flyers, issuance of press releases, and contacting houseboat owners. However, the occurrence of another CO-poisoning at Lake Powell underscores the need for rapid intervention through modification of boat designs. Finally, surveillance of CO poisonings must be improved. Definition of the hazard depends on improved recognition of boat-related CO poisonings and drownings by EMS personnel, emergency departments, and coroners and on more extensive environmental data collection. To assist with these efforts, the team is expanding the scope of this investigation to include other U.S. lakes. Lake Powell is one of many locations where similar conditions may exist. References

* Signs and symptoms consistent with CO poisoning (i.e., death, loss of consciousness, seizures, headache, nausea, confusion, weakness, and altered state of consciousness) with a laboratory-confirmed elevated carboxyhemoglobin level (>2% in children or nonsmoking adults and >9% in smoking adults or adults for whom smoking status is unknown) or known exposure to engine or generator exhaust and one of the following: 1) loss of consciousness with no other cause; 2) symptoms of CO poisoning (other than loss of consciousness) and association with a person who also experienced symptoms of CO poisoning; or 3) symptoms of CO poisoning that improved on removal from exposure. † 29 CFR 1910-146. Figure 1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 12/14/2000 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|