What to know

Review the timeline of major scientific and public health events in CDC's Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program (CLPPP).

2020s

October 23–29, 2022

- October 2022: Each year, National Lead Poisoning Prevention Week (NLPPW) is a call to bring together individuals, organizations, industry, and state, tribal, and local governments to increase lead poisoning prevention awareness in an effort to reduce childhood exposure to lead. NLPPW highlights the many ways parents can reduce children’s exposure to lead in their environment and prevent its serious health effects.

2021

- CLPPP celebrates the 30th anniversary of the program.

- February 5, 2021: Decreases in Young Children Who Received Blood Lead Level Testing During COVID-19 — 34 Jurisdictions, January–May 2020 was published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR).

- March 2021: CDC announced the availability of fiscal year (FY) 2021 funds to support primary and secondary prevention strategies for childhood lead poisoning prevention and surveillance through 2026.

2021

- March 2021: Blood Lead Levels in U.S. Children Ages 1–11 Years, 1976–2016 was published in Environmental Health Perspectives.

- May 14, 2021: The Lead Exposure and Prevention Advisory Committee (LEPAC) unanimously voted in favor of recommending lowering CDC’s blood lead reference value (BLRV) from 5 μg/dL to 3.5 μg/dL based on latest available National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data.

- October 28, 2021: CDC updated its blood lead reference value (BLRV) from 5 µg/dL to 3.5 µg/dL in response to the LEPAC recommendation made on May 14, 2021.

2020

- February 24, 2020: The Federal Register announced a notice of charter renewal for the LEPAC.

- April 2020: CDC CLPPP announced supplemental funding for current recipients during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- April 29, 2020: The LEPAC held its inaugural meeting.

- October 30, 2020: The LEPAC held its second meeting.

2010s

2019

- January/February 2019: CLPPP contributed to a Special Supplement to the Journal of Public Health Management and Practice on lead poisoning prevention.

- June 13, 2019: The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary approved the proposed Lead Exposure Prevention Advisory Committee (LEPAC) member nominations.

- June 14, 2019: CDC ended the term of the Lead Poisoning Prevention (LPP) Subcommittee to the National Center for Environmental Health (NCEH)/ATSDR Board of Scientific Counselors (BSC).

2018

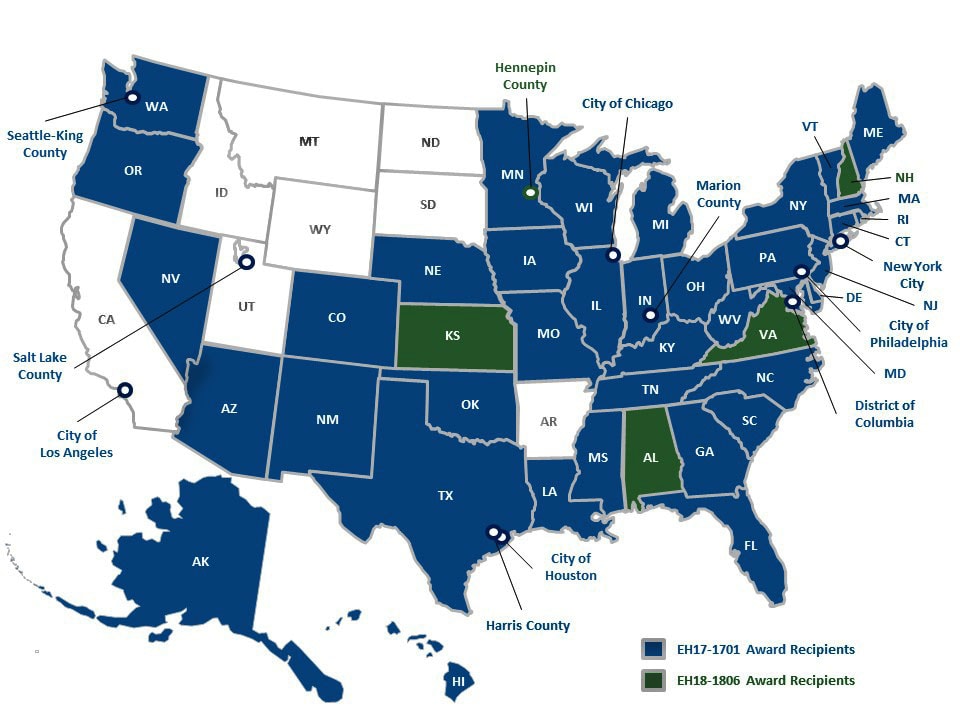

- CDC CLPPP funded 5 additional recipients throughout the nation for 2 years to conduct non-research activities focused on childhood lead poisoning prevention projects and state and local childhood lead poisoning prevention and surveillance of blood lead levels (BLLs) in children.

- February 13, 2018: The Federal Register announced a notice of charter establishment for the LEPAC.

- December 2018: The President’s Task Force on Environmental Health Risks and Safety Risks to Children released the Federal Action Plan to Reduce Childhood Lead Exposures and Associated Health Impacts.

2017

- The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a safety recall to discontinue using Magellan Diagnostics’ Lead-Care Testing Systems for analyzing venous blood samples. To promote accurate measurements of BLLs, CDC sponsored a voluntary external quality assurance program for laboratories.

- CDC CLPPP funded 14 recipients throughout the nation for 3 years to conduct non-research activities focused on lead poisoning prevention. Funding was financed partially by Prevention and Public Health funds.

December 2016

- The Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation (WIIN) Act allocated $35 million to CDC to enhance childhood lead poisoning prevention activities; to establish a voluntary Flint, Michigan, lead exposure registry; and to establish the LEPAC.

2016

- January 2016: A federal emergency was declared for the Flint Water Crisis. CDC provided assistance and support for response and recovery efforts.

- November 2016: The President’s Task Force on Environmental Health Risks and Safety Risks to Children report Key Federal Programs to Reduce Childhood Lead Exposures and Eliminate Associated Health Impacts cataloged federal efforts to understand, prevent, and reduce various sources of lead exposure among children.

October 2015

- After the involvement of concerned residents and independent researchers, Flint, Michigan, was reconnected to the Detroit water system.

2015

- March 2015: The LPP Subcommittee was created as part of the NCEH/ATSDR BSC.

- The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) designated BLLs ≥5 µg/dL as elevated for adults.

- The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) lowered the threshold for reporting lead emissions from point sources of air pollution to 0.5 tons per year of actual emissions.

2014

- The HHS Secretary designated lead poisoning prevention funds to be used to “support and enhance surveillance capacity” to end lead poisoning but did not include addressing the broader issue of healthy homes.

- CDC CLPPP funding was restored to $13 million – slightly more than one-third of pre-2012 funding levels; funds were used for surveillance, community-based strategies to target high-risk children and partnerships.

- Healthy People 2020 goals for lead poisoning prevention were met; from 2010 to 2014, there were reductions in BLLs between Black children and those of other races (37%) and between children living above and below the poverty line (46%).

- Using 2014 Prevention and Public Health funds, CDC CLPPP funded 35 recipients throughout the nation for 3 years to conduct non-research activities focused on lead poisoning prevention.

April 2014

- The drinking water source for Flint, Michigan, was switched from Great Lakes’ Lake Huron (provided by the Detroit Water and Sewage Department) to the Flint River without necessary corrosion control treatment to prevent lead release from pipes and plumbing.

October 31, 2013

- The charter for the Advisory Committee on Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention (ACCLPP) expired.

2012-2013

- CDC CLPPP appropriations were reduced to $2 million which resulted in the loss of extramural funding of state and local CLPPPs.

2012

- CDC replaced “blood lead level of concern” with “blood lead reference value” (BLRV) to identify children with BLLs that are much higher that most U.S. children; the BLRV is based on the 97.5 percentile of the estimated blood lead distribution in children age 1-5 years old using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

2010

- The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Promote Healthy Homes broadened CLPPP activities to include multiple health and safety housing hazards.

- Childhood lead poisoning prevention was named one of the “Ten Great Public Health Achievements in the United States (2001-2010).”

- CDC issued guidance that health care providers can use to trigger medical workplace removal for pregnant women with BLLs ≥ 10 µg/dL.

2000s

2009

- CDC released Guidelines for the Identification and Management of Lead Exposure in Pregnant and Lactating Women which provided scientific evidence and clinical guidance for identifying lead exposure in both mothers and infants.

2008

- Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act mandated reducing the lead limit in children’s products to 0.009% by weight.

- The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Renovation, Repair, and Painting (RRP) Rule was enacted to protect the public from lead-based paint (LBP)-hazards associated with renovation, repair and painting activities. The rule requires contractors that disturb LBP in pre-1978 homes and child-care centers to be EPA- or state-certified and to follow specific work practices to prevent lead contamination.

- EPA strengthened the National Ambient Air Quality Standard for lead from 1.5 µg/m3 to 0.15 µg/m3.

2005

- CDC updated Preventing Lead Poisoning in Young Children, which recommended lowering the BLL for home environmental investigations from 20 to 15 µg/dL.

2002

- CDC published Managing Elevated Blood Lead Levels Among Young Children, which explained components of a comprehensive case management plan based on the Advisory Committee on Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention (ACCLPP) recommendations.

2000

- The President’s Task Force on Environmental Health Risks and Safety Risks to Children released Eliminating Childhood Lead Poisoning: A Federal Strategy Targeting Lead Paint Hazards which made recommendations aiming for the elimination of childhood lead poisoning.

- The Lead and Copper Rule was revised to allow publicly owned sectors to conduct partial service line replacements.

1990s

1998 - 2010

- Yearly appropriated funding levels for CDC Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program (CLPPP) averaged $36 million through the mid-2000s. CDC recommended targeted screening and focused on improving surveillance.

1997

- CDC recommended targeted screening efforts to focus on high-risk neighborhoods and children based on age of housing and sociodemographic risk factors.

1996

- The ban on leaded gasoline for most motor vehicles became effective.

1995

- A total ban on food cans with lead solder, including imported cans, became effective.

- CDC collaborated with the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) to develop a national surveillance system for monitoring blood lead levels (BLLs) in the United States, and reporting of BLLs became the first noninfectious condition to be notifiable at the national level.

- CDC CLPPP began collecting blood lead surveillance data on children younger than 16 years from state health departments. Awarded $29 million in extramural awards.

1993

- The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) adopted CDC’s universal screening requirements for children receiving Medicaid benefits.

1992

- Title X of the Housing and Community Development Act (Residential Lead-Paint Hazard Reduction Act) expanded lead-based hazards to include lead-contaminated dust and soil and shifted response to a preventative strategy.

1991

- The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) released the Strategic Plan for the Elimination of Childhood Lead Poisoning that set forth a comprehensive agenda to eliminate childhood lead poisoning.

- CDC began promoting primary prevention activities, such as community-wide environmental interventions and education and nutritional campaigns, to lower children’s BLLs to <10 µg/dL.

- The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) published the Lead and Copper Rule to minimize lead and copper in drinking water and established a maximum contaminant level goal (MCLG) of zero for lead.

- CDC recommended screening by blood lead testing for virtually all children aged 1 to 5 years and that all children younger than 2 years be screened at least once.

1991-2012

- CDC’s “blood lead level of concern” was defined as children with BLLs ≥ 10 µg/dL.

1991-1997

- CDC CLPPP received full funding which supported a comprehensive program that recommended universal screening and provided guidance on case management.

1990

- The Clean Air Act Amendments issued a final ban on leaded gasoline for most motor vehicle use.

1980s

December 1989

- CDC established the Advisory Committee on Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention (ACCLPP) to provide advice to reduce the incidence and prevalence of childhood lead poisoning.

1988

- The Lead Contamination Control Act of 1988 authorized CDC to support local and state agencies to develop comprehensive childhood lead poisoning prevention programs (CLPPPs).

- CDC CLPPP adopted the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) approach to focus on the 3 core functions of public health: assessment, policy development, and assurance, as published in their landmark report The Future of Public Health.

- CDC and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) published the first report to Congress on The Nature and Extent of Lead Poisoning in Children in the United States.

1986

- Amendment of Safe Drinking Water Act required lead-free solder, flux, fittings, and pipes as of June 1988.

1985

- CDC updated screening recommendations for all children, with priority given to those exposed to older, dilapidated housing; who lived near heavily trafficked highways; who were siblings, housemates, visitors, or playmates of children with known lead toxicity; or whose family members had occupational lead exposures.

- CDC provided treatment guidelines for lead poisoning to state and local public health agencies.

1981

- Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981 cut appropriations for maternal and child health services by 25%. Block grants were provided to allow states to determine their own maternal and child health priorities, including lead poisoning prevention.

1970s

1978

- The Lead-Based Paint Poisoning Act of 1971 ban on lead-based paint (LBP) in residences constructed or rehabilitated by the federal government or with federal assistance became effective in 1978.

- CDC first defined “elevated blood lead level”.

- The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) set the National Ambient Air Quality Standard for lead at 1.5 µg/m3.

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) banned furniture, toys, and other articles with a surface lead content of 0.06% or higher by weight intended for use by children.

1976

- CDC used state-of-the-art technology to measure blood lead levels (BLLs) as part of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

1975

- CDC recommended screening for children at risk, defined primarily as those exposed to poorly maintained housing units constructed before 1960.

1974

- The Safe Drinking Water Act gave EPA authority to set limits on lead and other contaminants in drinking water.

1973

- CPSC banned hazardous amounts of lead in toys and other products intended for use by children and required warning labels on other lead-containing products under the Federal Hazardous Substances Act.

1972

- EPA initiated a health-based regulation to remove lead from gasoline.

1971

- The Lead-Based Paint Poisoning Act of 1971 prohibited LBP in residences constructed or rehabilitated by the federal government or with federal assistance and defined paint chips as the primary health hazard of LBP.

- The Surgeon General’s report defined “undue absorption of lead, either past or present” as 40 μg/dL and “lead poisoning” as confirmed, on 2 successive determinations, BLLs of 80 μg/dL or more with or without symptoms.

- CDC initiated a grant program for individual cities aimed at lead poisoning prevention (1971 – 1979).

Content Source:

National Center for Environmental Health