Key points

- Common symptoms of histoplasmosis include fever, cough, and malaise and are typically self-limiting.

- Chronic disseminated and severe cases require antifungals.

- Histoplasma antigen detection in urine and/or serum is one of the most sensitive diagnostic methods.

- Presumed Ocular Histoplasmosis Syndrome (POHS) may be a long-term complication.

- Refer to CDC's algorithm to guide diagnosis and treatment.

Etiology

The etiologic agents for histoplasmosis are Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum (near-worldwide distribution) and Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii (in Africa).

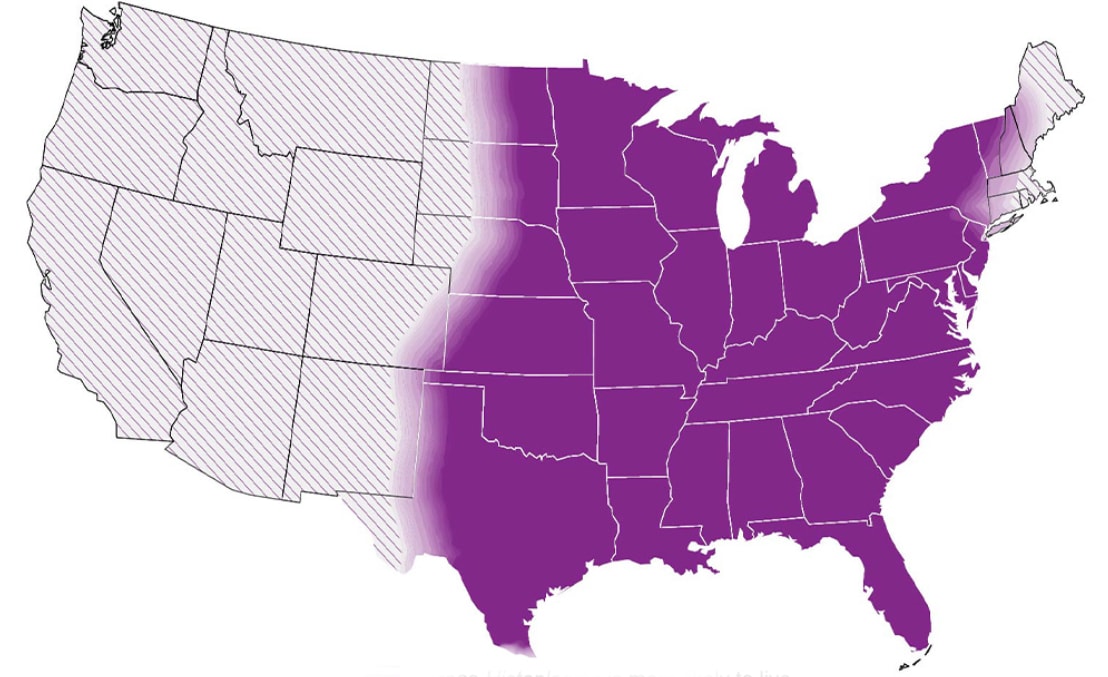

Histoplasma lives in soil, particularly soil that is heavily contaminated with bird or bat droppings. Endemic areas include the central and eastern United States, particularly areas around the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys. It is also found in Central and South America, Africa, Asia, and Australia. Histoplasma distribution is likely nationwide.

Risk factors

Disseminated histoplasmosis is more likely to occur in immunosuppressed persons including:

- people who have HIV/AIDS

- people who have had organ transplants

- people who use immunosuppressive medications

- infants

- adults age 55 years and older

How it spreads

Histoplasmosis is typically acquired via inhalation of airborne microconidia, often after disturbance of contaminated material. Some activities that increase risk include spelunking, cleaning chicken coops, construction, and landscaping. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis and solid organ donor-derived histoplasmosis are extremely uncommon.

Clinical features

Symptoms and severity

Severity of illness depends on host immunity and intensity of exposure. Symptomatic infections (1%) usually present 3 to 17 days after exposure. Symptoms of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis include fever, malaise, cough, headache, chest pain, chills, and myalgias. Persons with a history of pulmonary disease can develop chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis. Immunosuppressed persons are at risk for developing disseminated histoplasmosis.

Sequelae

Sequelae can include pericarditis, broncholithiasis, pulmonary nodules, mediastinal granuloma, or mediastinal fibrosis. In persons who develop progressive, chronic, or disseminated disease, symptoms may persist for months or longer. Mortality is high in people living with HIV who develop disseminated histoplasmosis.

Diagnosis

Histoplasma antigen detection in urine or serum is the most widely used and most sensitive method. Other methods include antibody tests, culture, and microscopy. The most appropriate diagnostic test may depend on clinical manifestation and severity.

Enzyme immunoassay (EIA) typically performed on urine or serum but can also be used on cerebrospinal fluid or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Urine antigen testing may have the highest sensitivity of non-invasive diagnostic tests and the quickest turnaround.

Development of antibodies to Histoplasma can take 2 to 6 weeks. Antibody tests are not as useful as antigen detection tests for diagnosing acute histoplasmosis. This is especially true in immunosuppressed persons, who may not mount a strong immune response. However, antibody tests can be used in combination with antigen tests to increase sensitivity.

Tests for the presence of H (indicates chronic or severe acute infection) and M (develops within weeks of acute infection). These persist for months to years after the infection has resolved; precipitin bands; ~80% sensitivity.

Complement-fixing antibodies may take up to 6 weeks to appear after infection. CF is more sensitive but less specific than immunodiffusion.

Can be performed on tissue, blood, and other body fluids, but may take up to 6 weeks to become positive; most useful in the diagnosis of the severe forms of histoplasmosis. A commercially available DNA probe (AccuProbe, GenProbe Inc.) can be used to confirm.

For detection of budding yeast in tissue or body fluids. It has low sensitivity but can provide a quick proven diagnosis if positive.

PCR for detection of Histoplasma directly from clinical specimens is not widely available; however, it can be performed on serum, tissue, or BAL fluid and is promising.

Treatment and recovery

Mild to moderate cases of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis will often resolve without treatment. Treatment is indicated for moderate to severe acute pulmonary, chronic pulmonary, disseminated, and central nervous system (CNS) histoplasmosis.

Antifungal agents proven effective are amphotericin B (including liposomal and lipid formulations) and itraconazole (for mild-to-moderate infections and step-down therapy). Therapeutic drug monitoring should be considered for certain antifungals like itraconazole when treating histoplasmosis.

Please refer to the following:

Reporting and statistics

Histoplasmosis is reportable in certain states. Check with your local public health department for more information about disease reporting procedures in your area. See facts and stats about histoplasmosis .

Presumed Ocular Histoplasmosis Syndrome

Presumed Ocular Histoplasmosis Syndrome (POHS), a condition that can cause vision loss, is being studied as a long-term complication of histoplasmosis.

The clinical manifestations of POHS include:

- "Punched out" round chorioretinal scars

- Peripapillary atrophy

- Absence of vitritis (i.e., inflammation of vitreous cavity of the eye)

- Choroidal neovascularization (CNV)

For some patients, chorioretinal scarring does not impair vision and only requires routine monitoring. Patients with both POHS and CNV often experience vision loss.

Treatment options include intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injections or photodynamic therapy (PDT). Scientists do not believe that people with POHS have active fungi in their eyes. As a result, unlike other fungal infections, antifungal medications are not typically recommended as treatment for POHS.

However, disseminated histoplasmosis infections involving the eye requires antifungal treatment. These infections are distinct from POHS and have rarely been reported.

Increasing awareness of POHS can help people seek care and get appropriate diagnosis and treatment sooner.

- Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis: a clinical and laboratory update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007 Jan;20(1):115-32.

- Manos NE, Ferebee SH, Kerschbaum WF. Geographic variation in the prevalence of histoplasmin sensitivity. Dis Chest. 1956 Jun;29(6):649-68.

- Colombo AL, Tobon A, Restrepo A, Queiroz-Telles F, Nucci M. Epidemiology of endemic systemic fungal infections in Latin America. Med Mycol. 2011 Nov;49(8):785-98.

- Loulergue P, Bastides F, Baudouin V, Chandenier J, Mariani-Kurkdjian P, Dupont B, et al. Literature review and case histories of Histoplasma capsulatum duboisii infections in HIV-infected patients. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007 Nov;13(11):1647-52.

- Chakrabarti A, Slavin MA. Endemic fungal infections in the Asia-Pacific region. Med Mycol. 2011 May;49(4):337-44.

- McLeod DS, Mortimer RH, Perry-Keene DA, Allworth A, Woods ML, Perry-Keene J, et al. Histoplasmosis in Australia: report of 16 cases and literature review. Medicine. 2011 Jan;90(1):61-8.

- Smith JA, Riddell Jt, Kauffman CA. Cutaneous manifestations of endemic mycoses. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2013 Oct;15(5):440-9.

- Roy M, Park BJ, Chiller TM. Donor-derived fungal infections in transplant atients. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2010;4:219-28.

- McKinsey DS, McKinsey JP. Pulmonary histoplasmosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011 Dec;32(6):735-44.

- Marukutira T, Huprikar S, Azie N, Quan SP, Meier-Kriesche HU, Horn DL. Clinical characteristics and outcomes in 303 HIV-infected patients with invasive fungal infections: data from the Prospective Antifungal Therapy Alliance registry, a multicenter, observational study. HIV/AIDS. 2014;6:39-47.

- Cuellar-Rodriguez J, Avery RK, Lard M, Budev M, Gordon SM, Shrestha NK, et al. Histoplasmosis in solid organ transplant recipients: 10 years of experience at a large transplant center in an endemic area. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Sep 1;49(5):710-6.

- Smith JA, Kauffman CA. Endemic fungal infections in patients receiving tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor therapy. Drugs. 2009 Jul 30;69(11):1403-15.

- Odio CM, Navarrete M, Carrillo JM, Mora L, Carranza A. Disseminated histoplasmosis in infants. Ped Infect Dis J. 1999 Dec;18(12):1065-8.

- Wheat LJ, Slama TG, Norton JA, Kohler RB, Eitzen HE, French ML, et al. Risk factors for disseminated or fatal histoplasmosis. Analysis of a large urban outbreak. Ann Intern Med. 1982 Feb;96(2):159-63.