Key points

- Inhibitors can prevent treatments from working, which makes it more difficult to stop a bleeding episode.

- Some people are more at risk for inhibitors than others.

- Inhibitors are diagnosed with blood tests and can be treated.

- Free inhibitor testing is available by participating in the Community Counts registry.

Why get tested

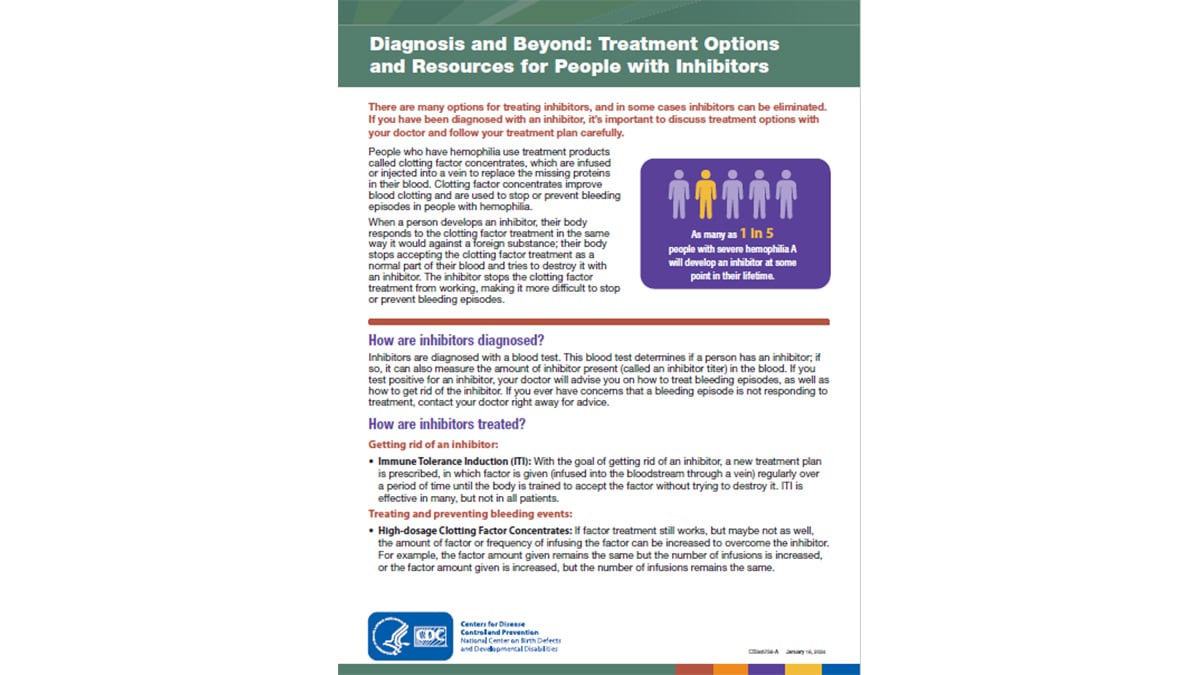

People with hemophilia have a better quality of life today than ever before, but medical complications can still occur. Approximately 1 in 5 people with hemophilia A1 and about 3 in 100 people with hemophilia B2 will develop an antibody—called an inhibitor—to the treatment product (medicine) used to treat or prevent their bleeding episodes. People with VWD type 3 may also develop inhibitors.

Developing an inhibitor is one of the most serious and costly medical complications of a bleeding disorder, because having an inhibitor makes it more difficult to treat bleeds. Inhibitors make it more difficult to stop a bleeding episode because they prevent the treatment from working.

If you have hemophilia or VWD type 3, it is important to be tested for inhibitors once a year. You can receive free inhibitor testing at federally funded hemophilia treatment centers (HTCs) by participating in the CDC Community Counts Registry for Bleeding Disorders Surveillance program.

About inhibitors

People with hemophilia, and many people with VWD type 3, use treatment products called clotting factor concentrates ("factor"). These treatment products improve blood clotting, and they are used to stop or prevent a bleeding episode. When a person develops an inhibitor, the body stops accepting the factor treatment product as a normal part of blood. The body thinks the factor is a foreign substance and tries to destroy it with an inhibitor. The inhibitor keeps the treatment from working, which makes it more difficult to stop a bleeding episode. A person who develops an inhibitor will require special treatment until their body stops making inhibitors. Inhibitors most often appear during the first 50 times a person is treated with clotting factor concentrates, but they can appear at any time.

Have a Bleeding Disorder? Get tested regularly for an inhibitor

Who should be tested

All people with hemophilia and VWD type 3 are at risk of developing an inhibitor. Scientists do not know exactly what causes inhibitors. Multiple research studies have shown that people with certain types of hemophilia gene mutations3 are more likely to develop an inhibitor.

Genes are inside all cells in the body, and they contain the instructions for the development and functioning of all living things. The genes that a person inherits from his or her parents can determine many things. For example, genes affect what a person will look like and whether the person might have certain diseases. Hemophilia is caused by changes, called mutations, within the genes that control blood clotting.

Some studies have found other characteristics that may play a role in increasing the risk of inhibitor development among people with hemophilia. These include the following:4

- Number of times one has used clotting factor concentrates in their lifetime

- Increased frequency and dose of treatment

- Black race or Hispanic ethnicity

- Family history of inhibitors (other family members who have had inhibitors)

Types of tests

Inhibitors are diagnosed with a blood test. The blood test measures if an inhibitor is present and the amount of inhibitor present (called an inhibitor titer) in the blood. Inhibitor titers are measured in Nijmegen-Bethesda units (NBU) if the lab test used was the Nijmegen-Bethesda assay (NBA), or Bethesda units (BU) if the lab test used was the Bethesda assay.

What a diagnosis means

A person with a high inhibitor titer has more inhibitor present in the blood compared to a person with a low inhibitor titer. Test results of 5.0 NBU/BU or lower are called "low titer" inhibitors, whereas test results of greater than 5.0 NBU/BU are called "high titer" inhibitors. People diagnosed with low titer inhibitors are more likely to have shorter and more successful inhibitor treatment than those with high titer inhibitors.5

For these reasons, it is important that all people with hemophilia or VWD type 3 who use clotting factor concentrates get tested for inhibitors at least once a year. Eligible individuals can receive free inhibitor testing at federally funded HTCs through the Community Counts Registry for Bleeding Disorders Surveillance.

After you get your results

If you are diagnosed with an inhibitor, it is important to get treatment. Treatment for people who have an inhibitor is complex, and it is one of the biggest challenges in the care of people with bleeding disorders. Some inhibitors, called "transient" inhibitors, may go away on their own, without treatment. If possible, a person with an inhibitor should consider seeking care at an HTC. HTCs are specialized healthcare centers that bring together a team of doctors (hematologists or blood specialists), nurses, and other health professionals experienced in treating people with bleeding disorders.

Some treatments for people with inhibitors include the following:

All inhibitor treatment options require specialized medical expertise. Treatment can be costly, particularly bypassing agents and ITI. It is important that people who are being treated for inhibitors have their blood tested often to measure their inhibitor titers to be sure that the treatment is working. HTCs can serve a vital role in supporting patients who undergo intensive treatment regimens, such as ITI, for inhibitors.

Cost of treatment for people with inhibitors

Treatment for people with an inhibitor poses special challenges. The healthcare costs associated with inhibitors can be very high because of the amount and type of treatment product required to stop bleeding. Also, people with hemophilia who develop an inhibitor are twice as likely to be hospitalized for a bleeding complication, and they are at increased risk of death.678 The excess cost of care for each person with hemophilia and an inhibitor is over $800,000 per year9 and, based on CDC surveillance data, there are nearly 1,500 people living with an inhibitor in the United States.

Diagnosis and Beyond Fact Sheet: Treatment Options and Resources for People with Inhibitors

Resources

The National Bleeding Disorders Foundation (NBDF) has held Inhibitor Education Summits. These summits are intended for patients, caregivers, and staff members from HTCs and NBDF chapter organizations. The summits allow attendees to learn from each other’s experiences and from experts. Past topics have addressed new drugs in development, tips for parents, sports and exercise, immune tolerance therapy, and needs of older adults with hemophilia and an inhibitor.

For more information, visit the NBDF Inhibitor Education website.

- Wight J, Paisley S. The epidemiology of inhibitors in haemophilia A: a systematic review. Haemophilia. 2003; 9(4):418-435.

- Puetz J, Soucie JM, Kempton CL, Monahan PE, and Hemophilia Treatment Center Network Investigators. Prevalent inhibitors in hemophilia B subjects enrolled in the Universal Data Collection database. Haemophilia. 2015; 20(1):25-31.

- Miller CH, Benson J, Ellingsen D, Driggers J, Payne A, Kelly FM, Soucie JM, Hooper CW, and the Hemophilia Inhibitor Research Study Investigators. F8 and F9 mutations in US haemophilia patients: correlation with history of inhibitor and race/ethnicity. Haemophilia. 2012; 18:375-382.

- Witmer C, Young G. Factor VIII inhibitors in hemophilia A: rationale and latest evidence. Therapeutic Advances in Hematology. 2013; 4(1):59-72.

- Hay CR, DiMichele DM, International Immune Tolerance Study. The principal results of the International Immune Tolerance Study: a randomized dose comparison. Blood. 2012; 119(6):1335-1344.

- Guh S, Grosse SD, McAlister S, Kessler CM, Soucie JM. Health care expenditures for males with haemophilia and employer-sponsored insurance in the United States. Haemophilia. 2012; 18(2):268-275.

- Guh S, Grosse SD, McAlister S, Kessler CM, Soucie JM. Health care expenditures for Medicaid-covered males with haemophilia in the United States, 2008. Haemophilia. 2012; 18(2):276-283.

- Walsh CE, Soucie JM, Miller CH; United States Hemophilia Treatment Center Network. Impact of inhibitors on hemophilia A mortality in the United States. American Journal of Hematology. 2015; 90:400-405.

- Zheng-Yi Zhou, Marion A. Koerper, Kathleen A. Johnson, Brenda Riske, Judith R. Baker, Megan Ullman, Randall G. Curtis, Jiat-Ling Poon, Mimi Lou & Michael B. Nichol. Burden of illness: direct and indirect costs among persons with hemophilia A in the United States. Journal of Medical Economics 2015;18:457-465.