Key points

The U.S. CDC Guatemala Country Office supported a variety of programs in Guatemala to increase COVID-19 vaccination in many of the country's most remote areas. CDC worked with the Ministry of Public Health and Welfare to develop COVID-19 radio and TV messaging on how vaccines reduce risk of serious illness and death. When boats and vehicles could go no further, health workers traveled by foot to remote communities to bring COVID-19 vaccines to residents.

Background

Guatemala first introduced COVID-19 vaccines for healthcare workers, older adults, and people with underlying conditions in May 2021. In September 2021, the government approved COVID-19 vaccines for everyone age 12 years and older.

Challenges

The number of people getting vaccinated was significantly higher in the capital, Guatemala City, and most urban areas. Access to COVID-19 vaccines was often much more difficult for people living in isolated and remote communities. People living in these hard-to-reach areas had limited access to COVID-19 vaccine information in their local languages. Misinformation and lack of trust in authorities also had an impact on people choosing to get vaccinated in many communities.

By September 2021, over 50% of the population in Guatemala City and the surrounding suburbs had received a COVID-19 vaccine. Guatemala is divided into 22 administrative areas called departments. In rural departments like Totonicapán, Sololá, Quiché, and Alta Verapaz, less than 20% of people over 18 years old had received their first COVID-19 vaccination.

The U.S. CDC Guatemala Country Office supported a variety of programs designed to increase COVID-19 vaccinations in many of the country's most remote areas.

Overcoming a decades-old problem to stop a new virus

In Guatemala, like many places around the world, how much you earn and where you live can affect access to basic health care services, including access to vaccines. Rural populations face significant access challenges, particularly in the more isolated areas of the country. Because the public health system is underfunded and understaffed, it can be very challenging for rural populations to receive high-quality health care near their homes.

Many rural areas have largely indigenous populations. An estimated 40% of Guatemalans belong to indigenous Mayan communities and a small percentage identify as Xinca or Garífuna. The majority of the population is mestizo (mixed European and indigenous heritage or of European ancestry).

Health officials in Guatemala wanted to get the COVID-19 vaccine to as many people as quickly as possible. For those who lived in remote areas of this Central American nation, some barriers were harder to overcome than others.

Raising awareness about the COVID-19 vaccine was not easy. People living in very remote areas often have poor mobile phone and television reception. Radio broadcasts are one of the few ways to get information to them. Early in the pandemic, most COVID-19 information was broadcast in Spanish.

This was a barrier to those living in communities where one of the 24 indigenous languages were spoken. Additionally, a lot of misinformation circulated in communities which created confusion and concern about COVID-19 vaccinations.

There are also important economic and cultural barriers to getting COVID-19 vaccinations. In the early days of the pandemic, vaccination centers were located at clinics or municipal centers. Getting to them could have a financial impact, requiring people to take time off from work, arrange for childcare, and pay for transportation.

Sometimes the vaccine was not available due to supply issues or concerns about not using all doses in a vial – resulting in an expensive trip made for nothing. A recent publication by Guatemalan and CDC partners showed that poverty, along with other factors, was a critical factor associated with low COVID-19 vaccination rates.

Vaccine confidence remained a big issue when health workers visited the most isolated areas where the disease was often ignored. In some areas, pastors would discourage members from getting vaccinated.

In Totonicapán, rejection of the vaccine was so widespread in some areas that local leaders told health workers they could not give COVID-19 vaccinations.

In Sololá, religious leaders from a popular evangelical church organized marches past the COVID-19 curfew to "defy the disease." In Izabal, some villages are only accessible by boat. In other regions, towns can only be reached with a four-wheel-drive vehicle, adding to the difficulties to bring vaccines to residents.

Interventions

Stretching limited resources to counter COVID-19 misinformation

Every health district in the country has a yearly budget of approximately 4,700 Guatemalan Quetzales (approximately $600 USD) to spend on health promotion and communication strategies for all public health issues. This limited budget makes it hard to create key messages to increase demand for the COVID-19 vaccines, stop misinformation, and work on other existing health challenges.

Recognizing the need for more resources, CDC's Guatemala Country Office, Guatemala's MOH, and the Task Force for Global Health partnered with Nutrition Institute of Central America and Panama (INCAP) to support efforts to develop communication strategies tailored to five of Guatemala's 29 health districts (Totonicapán, Petén Sur Oriente, Petén Norte, Petén Occidente, Sololá).

Each health department created six-month monitoring and action plans with strategies to increase COVID-19 vaccine coverage. The efforts used information from national anthropological survey results on vaccination hesitancy and focused on

- accessibility barriers

- education and communication

- research needs

- community-based orientations

CDC supported workshops to create campaign artwork and materials to increase vaccine uptake. More than 20 key leaders developed communication messages that easily explained the benefits of getting the COVID-19 vaccine.

The MOH and CDC's Guatemala Country office worked with local partners in Guatemala to find more solutions: INCAP and the Council of Ministers of Health of Central America and the Dominican Republic (COMISCA). With CDC support, both organizations were able to help get more people vaccinated. This work included:

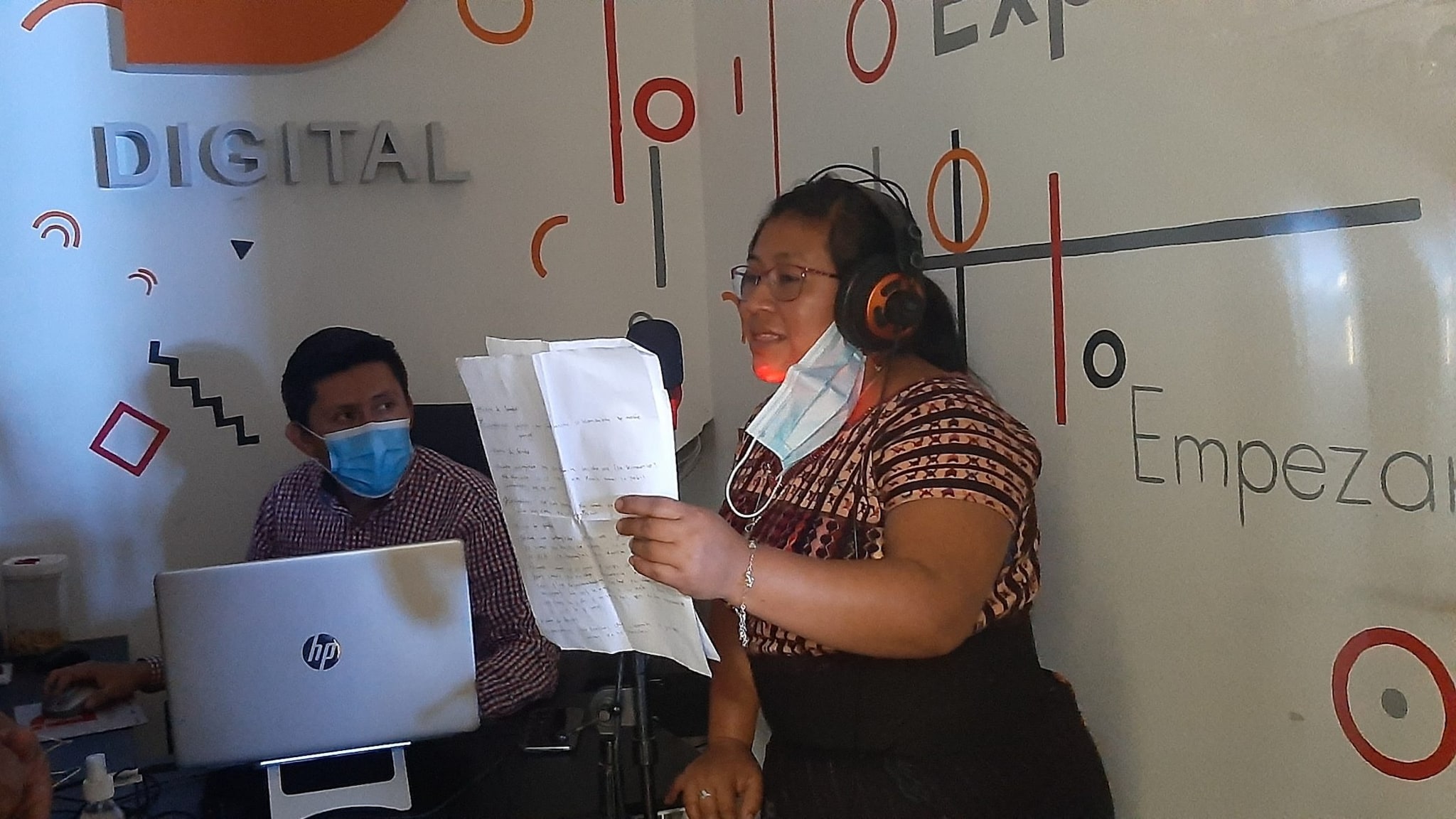

- Creating six radio spots in Tz'utujil (a Mayan language) and Spanish.

- Prioritizing campaigns where people in communities with the greatest level of vaccination resistance received COVID-19 information through face-to-face communication from local leaders and spokespersons.

- Supporting the mobilization of vaccination teams to offer vaccine within communities or door-to-door in locations where access was difficult.

These COVID-19 messages were distributed in radio and TV advertising campaigns and broadcast through loudspeakers on vehicles driving across different regions within each health sector. This support will continue through the end of September of 2023.

As additional funding became available, CDC, Guatemala's MOH and the Executive Secretariat of COMISCA worked together to expand vaccine availability in five of the lowest coverage municipalities, which are also primarily indigenous communities, in the departments of Izabal, Sololá, Totonicapán, Chimaltenango, and the towns of San Juan Ostuncalco and San Juan Sacatepéquez. At the same time, USAID was working with the MOH and other partners to focus efforts on the departments of Alta Verapaz, Huehuetenango, Quiché, and San Marcos.

Local health workers were key to Guatemala's efforts to vaccinate as many people as possible in remote areas. It was difficult work.

Walking the extra miles to reach more people

When boats and four-wheel-drive vehicles could go no further, health workers would walk to the most remote houses to vaccinate residents against COVID-19. Sometimes hostile residents threw rocks at them, forcing them to leave.

CDC Guatemala was quick to assess these situations and identify areas where health workers often struggle with transportation. CDC staff partnered with COMISCA to plan and deploy vehicles to transport health workers doing their vaccination rounds within the communities.