Paragonimiasis

[Paragonimus westermani] [Paragonimus spp.]

Causal Agents

More than 30 species of trematodes (flukes) of the genus Paragonimus have been reported which infect animals and humans. Among the more than 10 species reported to infect humans, the most common is P. westermani, the oriental lung fluke.

Life Cycle

The eggs are excreted unembryonated in the sputum, or alternately they are swallowed and passed with stool  . In the external environment, the eggs become embryonated

. In the external environment, the eggs become embryonated  , and miracidia hatch and seek the first intermediate host, a snail, and penetrate its soft tissues

, and miracidia hatch and seek the first intermediate host, a snail, and penetrate its soft tissues  . Miracidia go through several developmental stages inside the snail

. Miracidia go through several developmental stages inside the snail  : sporocysts

: sporocysts  , rediae

, rediae  , with the latter giving rise to many cercariae

, with the latter giving rise to many cercariae  , which emerge from the snail. The cercariae invade the second intermediate host, a crustacean such as a crab or crayfish, where they encyst and become metacercariae. This is the infective stage for the mammalian host

, which emerge from the snail. The cercariae invade the second intermediate host, a crustacean such as a crab or crayfish, where they encyst and become metacercariae. This is the infective stage for the mammalian host  . Human infection with P. westermani occurs by eating inadequately cooked or pickled crab or crayfish that harbor metacercariae of the parasite

. Human infection with P. westermani occurs by eating inadequately cooked or pickled crab or crayfish that harbor metacercariae of the parasite  . The metacercariae excyst in the duodenum

. The metacercariae excyst in the duodenum  , penetrate through the intestinal wall into the peritoneal cavity, then through the abdominal wall and diaphragm into the lungs, where they become encapsulated and develop into adults

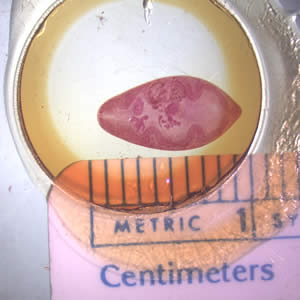

, penetrate through the intestinal wall into the peritoneal cavity, then through the abdominal wall and diaphragm into the lungs, where they become encapsulated and develop into adults  . (7.5 to 12 mm by 4 to 6 mm). The worms can also reach other organs and tissues, such as the brain and striated muscles, respectively. However, when this takes place completion of the life cycles is not achieved, because the eggs laid cannot exit these sites. Time from infection to oviposition is 65 to 90 days. Infections may persist for 20 years in humans. Animals such as pigs, dogs, and a variety of feline species can also harbor P. westermani.

. (7.5 to 12 mm by 4 to 6 mm). The worms can also reach other organs and tissues, such as the brain and striated muscles, respectively. However, when this takes place completion of the life cycles is not achieved, because the eggs laid cannot exit these sites. Time from infection to oviposition is 65 to 90 days. Infections may persist for 20 years in humans. Animals such as pigs, dogs, and a variety of feline species can also harbor P. westermani.

Geographic Distribution

Paragonimus spp. are distributed throughout the Americas, Africa and southeast Asia. Paragonimus westermani is distributed in southeast Asia and Japan. Paragonimus kellicotti is endemic to North America.

Clinical Presentation

The acute phase (invasion and migration) may be marked by diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, cough, urticaria, hepatosplenomegaly, pulmonary abnormalities, and eosinophilia. During the chronic phase, pulmonary manifestations include cough, expectoration of discolored sputum, hemoptysis, and chest radiographic abnormalities. Extrapulmonary locations of the adult worms result in more severe manifestations, especially when the brain is involved.

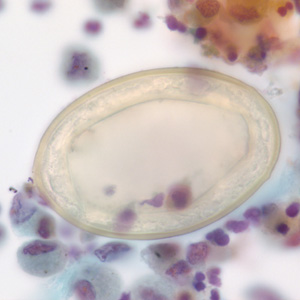

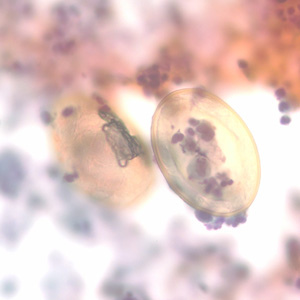

Eggs of Paragonimus spp. in unstained wet mounts.

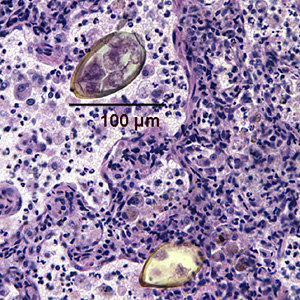

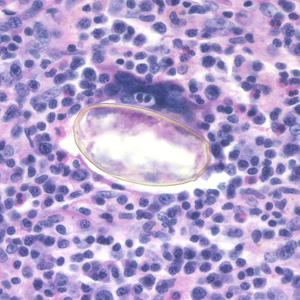

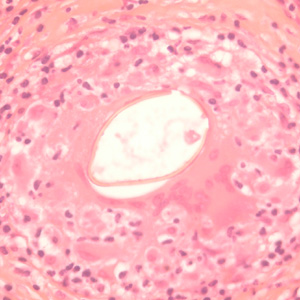

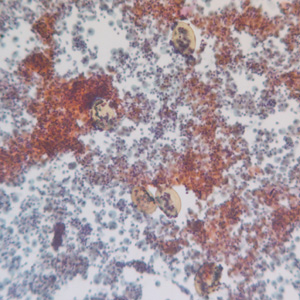

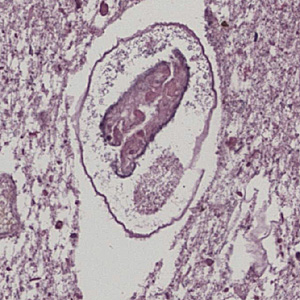

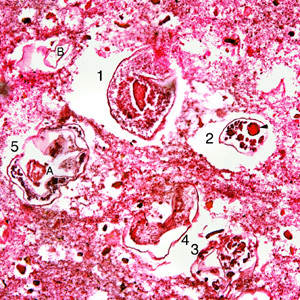

Eggs of Paragonimus spp. in tissue.

Eggs of Paragonimus kellicotti.

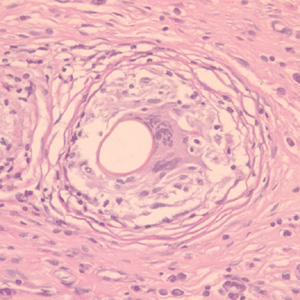

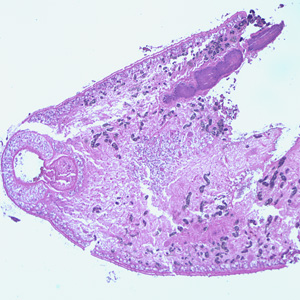

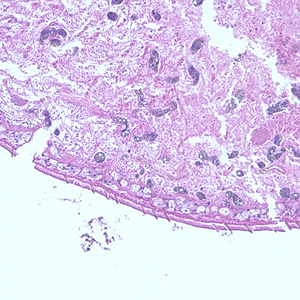

Adults of Paragonimus spp.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Morphologic Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on microscopic demonstration of eggs in stool or sputum, but these are not present until 2 to 3 months after infection. (Eggs are also occasionally encountered in effusion fluid or biopsy material.) Concentration techniques may be necessary in patients with light infections. Biopsy may allow diagnostic confirmation and species identification when an adult or developing fluke is recovered.

More on: Morphologic comparison with other intestinal parasites.

Antibody Detection

Pulmonary paragonimiasis is the most common presentation of patients infected with Paragonimus spp., although extrapulmonary (cerebral, abdominal) paragonimiasis may occur. Detection of eggs in sputum or feces of patients with paragonimiasis is often very difficult; therefore, serodiagnosis may be very helpful in confirming infections and for monitoring the results of individual chemotherapy. In the United States, detection of antibodies to Paragonimus westermani has helped physicians differentiate paragonimiasis from tuberculosis in Indochinese immigrants. The complement fixation (CF) test has been the standard test for paragonimiasis; it is highly sensitive for diagnosis and for assessing cure after therapy. Because of the technical difficulties of CF, enzyme immunoassay (EIA) tests were developed as a replacement. The immunoblot (IB) assay performed with a crude antigen extract of P. westermani has been in use at CDC since 1988. Positive reactions, based on demonstration of an 8-kDa antigen-antibody band were obtained with serum samples of 96% of patients with parasitologically confirmed P. westermani infection. Specificity was >99%; of 210 serum specimens from patients with other parasitic and non-parasitic infections, only 1 serum sample from a patient with Schistosoma haematobium reacted. Antibody levels detected by EIA and IB do decline after chemotherapeutic cure but not as rapidly as those detected by the CF test. Most published literature deals with pulmonary paragonimiasis due to P. westermani although in some geographic areas other Paragonimus species cause similar or distinct clinical manifestations in human infections. Cross-reactivity between species does occur but at varying levels for different species. Thus, use of a test for P. westermani may not allow detection of antibodies to other Paragonimus species.

Reference:

Slemenda SB, Maddison SE, Jong EC, Moore DD. Diagnosis of paragonimiasis by immunoblot. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1988;39:469-471.

Treatment Information

Treatment information for paragonimus can be found at:

DPDx is an educational resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention, control, and treatment visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.