What to know

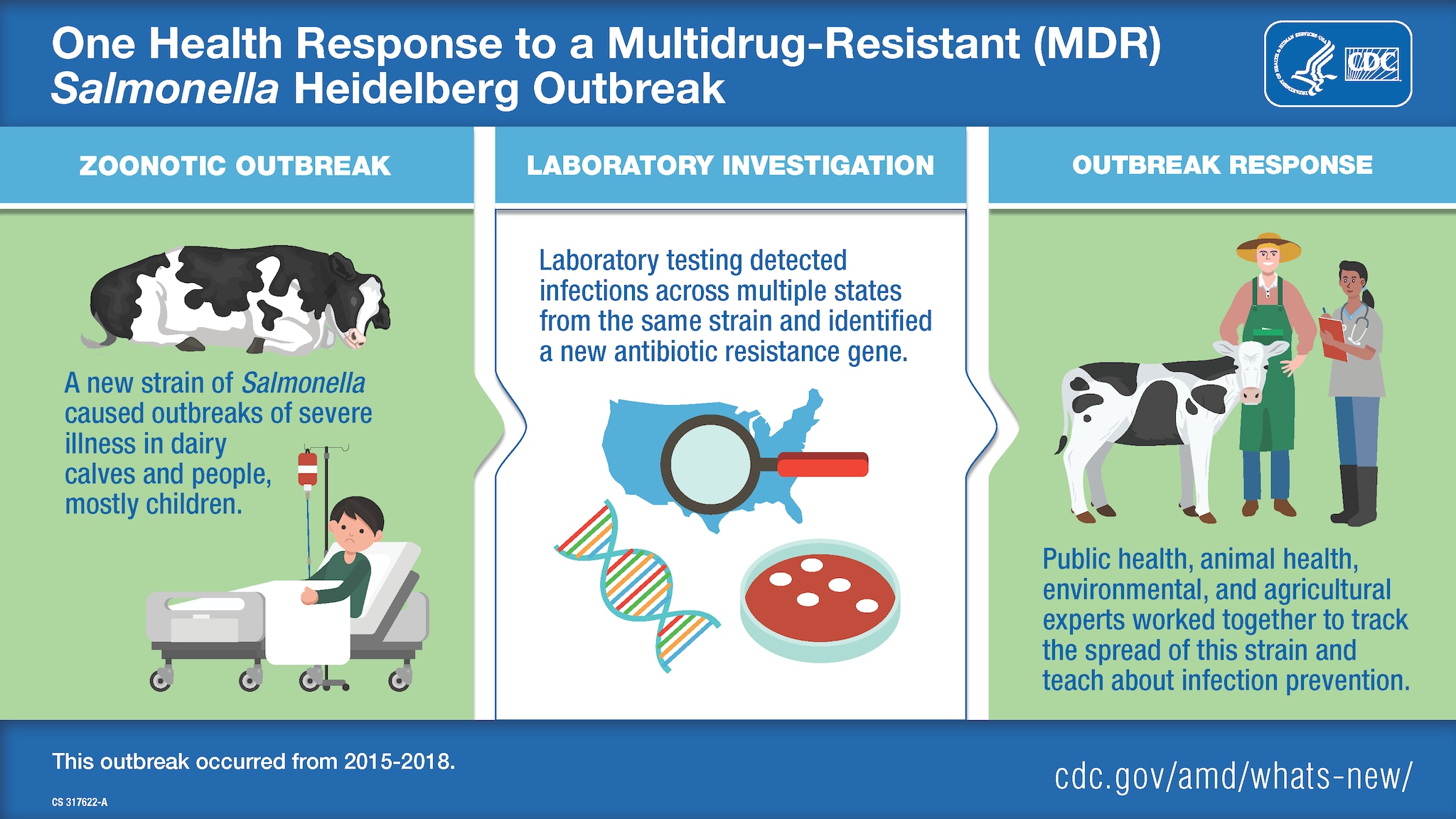

The use of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and a One Health approach aid in tracking and controlling outbreaks of multidrug-resistant bacteria. In 2016, the collaboration between public health, veterinary, and environmental sectors helped to slow the spread of disease in cattle and people.

Overview

One Health is an approach that recognizes the interconnectedness of the health of people, animals, and the environment. It involves collaboration across human and animal health, the environment, and other relevant sectors. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria have developed the ability to defeat the drugs designed to kill them and are an important One Health issue. Today, advanced molecular detection technologies, such as whole-genome sequencing (WGS), allow scientists to study how antibiotic resistance evolves and spreads. WGS also provides important information for responding to disease outbreaks. In a 2015–2018 outbreak of multidrug-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg, WGS revealed that the outbreak in people was connected to contact with dairy calves and calf environments.

An astute veterinarian

In January 2016, Dr. Donald Sockett, a veterinary microbiologist and epidemiologist at the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (WVDL), noticed that dairy calves at some facilities in Wisconsin and surrounding states were getting sick and dying. In some facilities, 25–50% of the calves were getting sick, most often within days of purchase from a livestock market or farm. The illness came on suddenly; calves that looked healthy in the morning were dead by the afternoon. Initial WVDL testing showed that the calves were carrying a strain of Salmonella serotype Heidelberg bacteria. Although Dr. Sockett and his veterinary colleagues study Salmonella from cattle in Wisconsin and other states, none of them had ever seen a Salmonella strain that caused such a rapid onset of illness or such a high death rate in calves.

A strong local One Health partnership

To gain a better understanding of the Salmonella Heidelberg bacteria causing illness and death in calves, WVDL asked its public health partners at the Wisconsin Department of Health Services (WDHS) to test bacteria sampled from sick calves. The public health laboratory tested the Salmonella Heidelberg bacteria using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), which provided an initial DNA fingerprint of the bacteria. That's when the scientists discovered that the bacteria collected from sick calves matched bacteria collected from people sickened in an ongoing outbreak of human Salmonella Heidelberg infections. The strain caused severe illness with rates of bloodstream infections and hospitalizations higher than usual for Salmonella. Initial antibiotic susceptibility testing in Wisconsin showed that the samples from both calves and people had the same multidrug-resistant patterns.

The role of whole-genome sequencing

Next, Wisconsin veterinarians and public health officials asked CDC to assist with characterizing the Salmonella bacteria strains using WGS. WGS helped scientists identify and understand the bacteria in a more detailed and precise way than PFGE could.

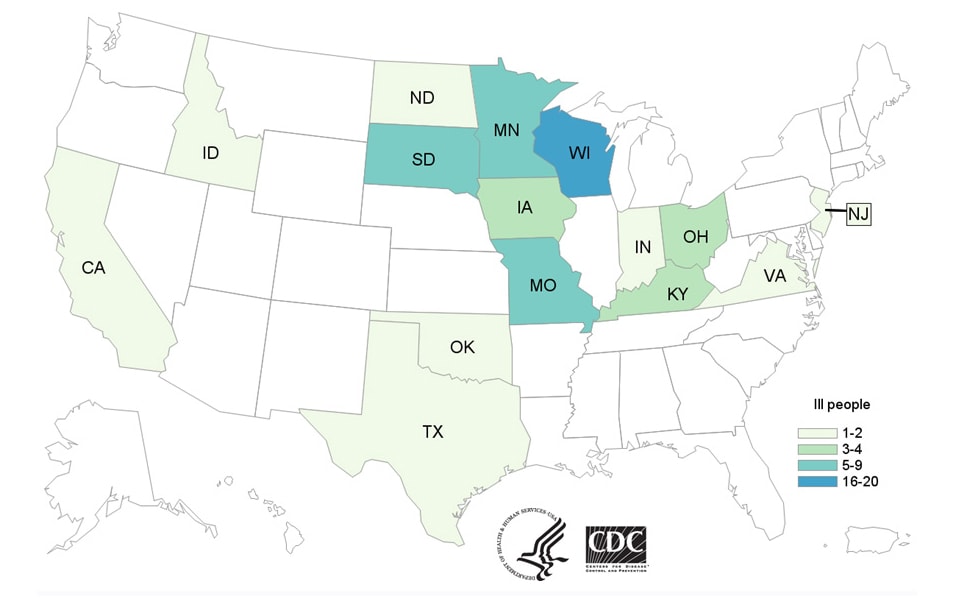

CDC's PulseNet team examined WGS data from Salmonella Heidelberg strains from Wisconsin and other state laboratories. Many strains that appeared to be different using PFGE testing were found to be genetically similar when compared using WGS, indicating that the strains were all related. CDC also determined that the Heidelberg strain was making people sick in several other states.

The National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) team at CDC conducted antibiotic susceptibility testing and confirmed resistance or decreased susceptibility to multiple antibiotics, including several used to treat human Salmonella infections. Using WGS, NARMS laboratory scientists took a closer look at the Salmonella bacterial genomes and identified genes typically responsible for antibiotic resistance. With this detailed molecular information, the NARMS team found that the pattern of resistance had not been detected in Salmonella Heidelberg before this outbreak. And, notably, this particular Heidelberg strain contained a newly identified antibiotic resistance gene.

Slowing the spread of disease

Outbreak investigators used WGS to track illnesses caused by the outbreak strain in 15 states across the country. Epidemiologic investigations confirmed the connection between sick people and contact with cattle. Many ill people had contact with dairy calves after buying them at sale barns and livestock markets.

Public health, veterinary, environmental, and agricultural experts came together to help slow the spread of disease. WDHS and CDC distributed messages that included advice for livestock handlers and veterinarians. They also disseminated information to help guide healthcare providers on treatment decisions.

In addition, animal health officials from Wisconsin and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) took environmental samples at a livestock market, farms, and other facilities to detect areas where Salmonella Heidelberg was present on surfaces. This helped them determine where to target enhanced cleaning and infection control procedures. Animal health officials also visited veterinarians and livestock producers to provide educational information and technical assistance on how to control the spread of the outbreak.

By using a One Health approach to communicate, collaborate, and coordinate response efforts, laboratory scientists, veterinarians, public health authorities, and educators on animal and human health were able to slow the spread of disease in cattle and people. Now, when Dr. Sockett investigates Salmonella outbreaks in animals, he works with public health officials to see if there might be illnesses in people with the same strain of Salmonella bacteria. He continues to use this story when providing outreach to veterinarians and livestock producers about antibiotic stewardship, infection control, and the potential impacts on human, animal, and environmental health.

Wisconsin's public health, veterinary, and environmental health partnership exemplifies the strong One Health collaboration that helps track antibiotic resistance and identify multistate outbreaks. Lessons from this outbreak of multidrug-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg infections have shaped practices to identify, control, and prevent outbreaks that threaten the health of both animals and people.