Disparities in Suicide

Suicide and suicide attempts are serious public health challenges. These events can have lasting emotional, mental, and physical health impacts, as well as economic consequences. They can also impact people who struggle with their own risk of suicide and/or mental health challenges (called lived experience).

Suicide and suicidal behavior are influenced by negative conditions in which people live, play, work, and learn. These conditions, sometimes called social determinants of health, can include racism and discrimination in our society, economic hardship (such as high unemployment), poverty, limited affordable housing, lack of educational opportunities, and barriers to physical and mental healthcare access, among others. Additional factors that can increase suicide risk include relationship problems or feeling a lack of connectedness to others, easy access to lethal means among people at risk, experiences of violence1 such as child abuse and neglect, adverse childhood experiences, bullying, and serious health conditions.

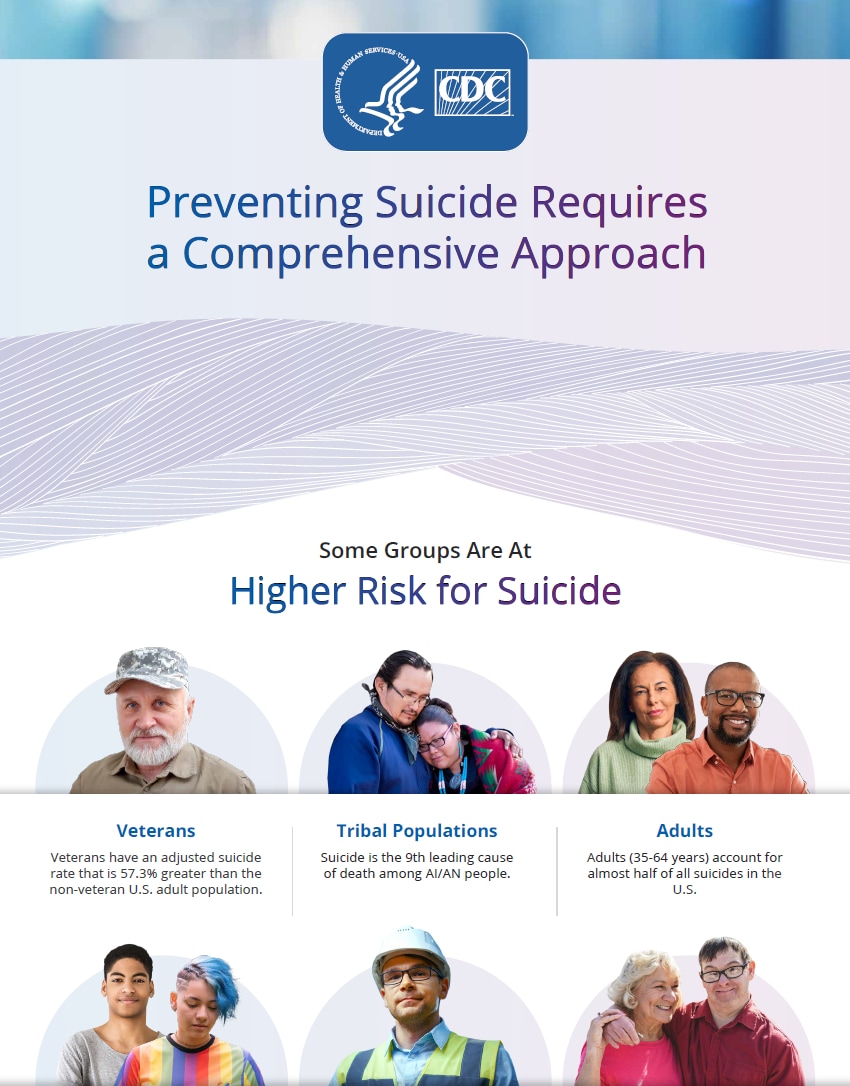

Some groups experience more negative conditions or factors related to suicide. While anyone can experience suicide risk, some populations experience more negative social conditions and other factors described above and have higher rates of suicide or suicide attempts than the general U.S. population. The excess burden of suicide in some populations are called health disparities.2 Examples of groups experiencing suicide health disparities include veterans, people who live in rural areas, sexual and gender minorities, middle-aged adults, people of color, and tribal populations.

Addressing these negative conditions and factors can help prevent suicide and suicide attempts. CDC is concerned with groups disproportionately impacted by suicide and uses a holistic, or comprehensive public health approach, to reduce suicide risk and promote resilience and well-being in communities, in order to save lives.

Click here [PDF – 1 MB] to access the Suicide Disparities infographic.

CDC is supporting states, tribes, territories, non-governmental organizations, and university research programs to address four strategic priority areas in suicide prevention:

- Data: Using new and existing data to better understand, monitor, and prevent suicide and suicidal behavior

- Science: Identifying risk and protective factors and effective policies, programs, and practices for suicide prevention in populations at increased risk for suicide

- Action: Building the foundation for CDC’s National Suicide Prevention Program

- Collaboration: Developing and implementing wide-reaching partnership and communication strategies to raise awareness and advance suicide prevention activities

Additionally, CDC funds the Comprehensive Suicide Prevention program, which aims to reduce suicide among groups that experience health disparities in suicide. These programs use suicide prevention strategies based on the best available evidence to help states and communities prevent suicide. These strategies can be found in CDC’s Suicide Prevention Resource for Action, and include:

- Strengthen economic supports

- Create protective environments

- Improve access and delivery of suicide care

- Promote healthy connections

- Teach coping and problem-solving skills

- Identify and support people at risk

- Lessen harms and prevent future risk

Adults

Adults aged 35–64 years account for 46.8% of all suicides in the United States, and suicide is the 8th leading cause of death for this age group.3

- Among men in this age group, suicide rates were highest for non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN) men (41.3 suicides per 100,000), followed by non-Hispanic White men (35.7 per 100,000).3

- Among women in this age group, suicide rates were highest among non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native women (12.8 per 100,000) and non-Hispanic White women (10.7 per 100,000).3

Older Adults

Adults aged 75 and older have one of the highest suicide rates (20.3 per 100,000). Men aged 75 and older have the highest rate (42.2 per 100,000) compared to other age groups. Non-Hispanic White men have the highest suicide rate compared to other racial/ethnic men in this age group (50.1 per 100,000).3

What CDC and funded partners are doing to prevent suicide among middle-aged adults

Massachusetts, Michigan, and Maine are working to reduce suicide disparities in middle-aged adults. Massachusetts and Maine are implementing gatekeeper training, which teaches community members how to identify people at risk for suicide and refer them to care. Massachusetts is also training providers to identify and support at-risk middle-aged adults and to use evidence-based screening and treatments.

Massachusetts also aims to reduce access to lethal means by promoting safe storage. Massachusetts is working to increase access to and education on the benefits of firearm storage safes and trigger locks, and to promote lock bags, locked cabinets, and safe disposal of over-the-counter drugs among middle-aged males.

For more information on what funded states are doing to prevent suicide, visit: Comprehensive Suicide Prevention: Program Profiles.

Youth and young adults ages 10–24 years account for 15% of all suicides. The suicide rate for this age group (11.0 per 100,000)** is lower than other age groups.3 However, suicide is the second leading cause of death for this age group, accounting for 7,126 deaths.3 Additionally, suicide rates for this age group increased 52.2% between 2000-2021.

Youth and young adults most impacted include non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native, with a suicide rate of 36.3 per 100,000.3

Youth and young adults have high rates of emergency department (ED) visits for self-harm. In 2020, ED visits for this age group were 354.4 per 100,000, compared with 128.9 per 100,000 among middle-aged adults ages 35-64 years.4

- There were an estimated 224,341 ED visits for self-harm among youth and young adults.4 Girls and young women are at particularly high risk, with their ED visit rate (514.4 per 100,000) being approximately twice the rate of ED visits among boys and young men (200.5 per 100,000).

- The rate of ED visits among girls in 2020 was approximately double compared to 2001 (244.3 per 100,000).4

In 2021, 9% of high school students reported attempting suicide during the previous 12 months.5 Suicide attempts were reported most frequently among girls compared to boys (12.4% vs. 5.3%) and among non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native students (20.1%).5

*Rates reflect 2021 data unless otherwise noted.

**All rates listed are crude, unless otherwise noted as age-adjusted rates. Age-adjusting rates refers to adjusting based on the “standard” population; this is done to ensure that the differences are not due to differences in the age distributions of the populations being compared. For example, comparing two states would usually require age-adjustments because some states may have older populations than others. Age-adjusting is not necessary when comparing age groups.

What CDC and funded partners are doing to prevent youth suicide

- Colorado, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Tennessee are working with their states’ departments of education to advance and provide social-emotional learning programs to promote coping and problem-solving skills.

- Colorado, Connecticut, North Carolina, and Vermont have implemented Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (CALM) in EDs to educate families of youth who are at increased risk for suicide on safe storage of lethal means (such as firearms, medications, and sharp objects) within the home.

For more information on what funded states are doing to prevent suicide, visit: Comprehensive Suicide Prevention: Program Profiles.

Data are limited on the rate of suicide among people who identify as sexual minorities. However, research shows that high school students who identify as sexual minorities have higher rates of suicide attempts compared to heterosexual students.5

In 2021, more than a quarter (26.3%) of high school students identifying as lesbian, gay, or bisexual reported attempting suicide in the prior 12 months. This rate was five times higher than the rate reported among heterosexual students (5.2%).5

Data from 2020 show the rate of self-reported suicide attempts in the prior 12 months among adult sexual minorities decreased with age, from 5.5% among people ages 18-25 to 2.2% among people ages 26-49.7

What CDC and funded partners are doing to prevent suicide among sexual minorities

Maine is working on promoting connectedness among sexual minority youth by:

- Implementing a program to enhance resiliency among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth both in and out of school.

- Promoting a training to equip youth-serving providers with skills in facilitating family connectedness and positive relationships among LGBT young people and their caregivers.

In 2020, 6,146 veterans died by suicide. Suicide was the 13th leading cause of death among veterans overall, and the second leading cause of death among veterans under age 45.8 Veterans have an adjusted suicide rate that is 57.3% greater than the non-veteran U.S. adult population.8 Veterans account for about 13.9% of suicides among adults in the United States.8

Additionally, in 2019, 1.6% of veteran young adults ages 18-25 reported making a suicide attempt during the previous 12 months. This was an increase from 0.9% in 2009.9

What CDC and funded partners are doing to prevent suicide among veterans

Massachusetts, North Carolina, Louisiana, and the University of Pittsburgh are identifying and supporting veterans at risk by implementing gatekeeper training.

- Massachusetts is requiring all staff working in Massachusetts Career Centers to complete gatekeeper training.

- North Carolina offers gatekeeper training as an option to healthcare providers.

- University of Pittsburgh provides gatekeeper trainings that teaches about risk factors and warning signs for suicide among veterans.

- Louisiana implemented gatekeeper trainings in nine local health department regions serving veterans.

Massachusetts, Louisiana, and the University of Pittsburgh are promoting connectedness among veterans.

- Massachusetts is focusing on community engagement to increase diversity, inclusion, and representation of veterans on the MassMen website. MassMen features articles, blog posts, self-assessments, and men’s stories to help men find solidarity, promote wellness, and increase help-seeking.

- The University of Pittsburgh is implementing community greening projects to promote connectedness and decrease social isolation among veterans in Pennsylvania.

- Louisiana is developing peer-to-peer norm groups with veterans. Peer norm programs seek to promote connectedness and normalize protective factors for suicide such as help-seeking, reaching out, and talking to trusted friends and loved ones.

North Carolina, Louisiana, and the University of Pittsburgh are strengthening access to and delivery of suicide care. North Carolina and Louisiana are providing increased veteran access to telemental health services to reduce provider shortages. The University of Pittsburgh is working to strengthen access to and delivery of suicide care for veterans by working toward equal coverage of mental health conditions. The University of Pittsburgh is also working to raise awareness and education among healthcare providers and community members on existing mental health parity laws.

For more information on what funded states are doing to prevent suicide, visit: Comprehensive Suicide Prevention: Program Profiles.

Age-adjusted suicide rates are highest among non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) people (28.1 per 100,000) and non-Hispanic White people (17.4 per 100,000).3

- Suicide is the 9th leading cause of death among AI/AN people.

- Non-Hispanic AI/AN people have a higher age-adjusted rate of suicide (28.1 per 100,000) compared with Hispanic AI/AN people (2.0 per 100,000).

- The suicide rate among non-Hispanic AI/AN males ages 15–34 is 82.1 per 100,000.

- Suicide is the 11th leading cause of death for both Hispanic and non-Hispanic people of all races.

- Between 2018-2021, suicide rates significantly increased overall among non-Hispanic AI/AN (26%) and non-Hispanic Black (19.2%) people, and declined by 3.9% among non-Hispanic White people.

What CDC and funded partners are doing to prevent suicide in tribal communities

Southern Plains Tribal Health Board and Wabanaki Public Health and Wellness are working to increase capacity to adapt, implement, and evaluate suicide prevention programs to reduce suicide-related morbidity and mortality. Each tribal organization is:

- Reviewing existing data to describe the general problem and identify a subgroup that is at increased risk for suicide compared to the general tribal population.

- Developing an inventory of existing suicide prevention programs for the general tribal population and the selected subgroup to identify gaps and opportunities that will complement existing programs.

- Selecting at least one program from CDC’s Suicide Prevention Resource for Action, or another evidence-informed program, to fill prevention gaps and complement existing programs.

- Adapting the selected program to fit the cultural context of the tribe and implement and evaluate the approach or program.

- Conducting listening sessions to obtain input during the project to adapt the approach of program.

- Disseminating results, success stories, and lessons learned.

For more information on CDC’s funded tribal suicide prevention program, visit: Tribal Suicide Prevention.

Limited data are available on suicide among people with disabilities. However, a recent survey highlighted that in 2021, adults with disabilities were three times more likely to report suicidal ideation in the past month compared to people without disabilities (30.6% versus 8.3% in the general U.S. population).10 Prior research also shows that the prevalence of reported mental distress, which is a risk factor for suicide, was 4.6 times higher among people with disabilities (32.9%) than among people without disabilities (7.2%).11

What CDC and funded partners are doing to prevent suicide among people with disabilities

- Vermont is working to reduce suicide disparities among people with disabilities by providing training to primary care providers to promote safe storage among this population.

- Vermont is supplementing and scaling up the state’s Zero Suicide work by engaging primary care providers serving people with disabilities.

For more information on what funded states are doing to prevent suicide, visit: Comprehensive Suicide Prevention: Program Profiles.

Industry is the type of activity at a person’s workplace and occupation is the kind of work a person does to earn a living. A CDC study examining data in 32 states found that the suicide rate among workers in certain industries and occupations was significantly greater than the general U.S. population, particularly for males.12

The industry groups that had the highest suicide rates were:

- Mining, Quarrying, and Oil and Gas Extraction (males: 54.2 per 100,000)

- Construction (males: 45.3 per 100,000)

- Other Services (such as automotive repair; males: 39.1 per 100,000)

- Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing, and Hunting (males: 36.1 per 100,000)

- Transportation and Warehousing (males: 29.8 per 100,000; females: 10.1 per 100,000)

The occupation groups that had higher suicide rates than the general population were:

- Construction and Extraction (males: 49.4 per 100,000; females: 25.5 per 100,000)**

- Installation, Maintenance, and Repair (males: 36.9 per 100,000)

- Arts, Design, Entertainment, Sports, and Media (males: 32.0 per 100,000)

- Transportation and Material Moving (males: 30.4 per 100,000; females: 12.5 per 100,000)

- Protective Service (females: 14.0 per 100,000)

- Healthcare Support (females: 10.6 per 100,000)

† Rates reflect 2016 data from 32 states

**Among females, no other occupation group had a rate of suicide greater than the general female population

What CDC and funded partners are doing to prevent suicide for people in at-risk occupations

Massachusetts, Colorado, and Connecticut are promoting connectedness among people working in occupations that are at greater risk for suicide.

- Massachusetts and Colorado are implementing peer norm programs for at-risk occupations, such as Signs of Suicide (S.O.S.).

- Connecticut is supporting community engagement efforts and providing workplaces for at-risk occupations with suicide prevention resources and materials.

- Massachusetts and Connecticut are identifying and supporting occupations at higher risk for suicide via healthcare provider education.

- Massachusetts, Connecticut, Michigan, and Colorado are promoting the implementation of organizational policies and culture in workplaces to create protective environments for people in at-risk occupations.

The workplace provides an important opportunity for suicide prevention efforts because it is where many adults spend a great deal of their time. Visit the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health website for more information about workplace suicide prevention strategies.

For more information on what funded states are doing to prevent suicide, visit: Comprehensive Suicide Prevention: Program Profiles.

Suicide rates can vary substantially across geographic regions.* For example, suicide rates increase as population density decreases and an area becomes more rural.

2021 suicide rates based on population density:

- Large central metropolitan: 11.6 per 100,000

- Large fringe metro: 12.8 per 100,000

- Medium metro: 15.7 per 100,000

- Small metro: 17.8 per 100,000

- Micropolitan (non-metro): 19.2 per 100,000

- Noncore (non-metro): 21.7 per 100,000

Suicide rates in rural (non-metro) areas are highest among non-Hispanic AI/AN males (61.8 per 100,000) and non-Hispanic White males (36.8 per 100,000).3

*For information on how areas are classified, visit this page: Data Access – Urban Rural Classification Scheme for Counties (cdc.gov)

What CDC and funded partners are doing to prevent suicide in rural communities

- North Carolina and Vermont are promoting safe storage of firearms in rural areas to reduce access to lethal means.

- North Carolina and Tennessee are identifying and supporting people at risk. Both states are also implementing gatekeeper trainings in rural counties and areas. North Carolina is promoting gatekeeper trainings among staff in rural schools.

For more information on what funded states are doing to prevent suicide, visit: Comprehensive Suicide Prevention: Program Profiles.

- Preventing Multiple Forms of Violence: A Strategic Vision for Connecting the Dots. Atlanta, GA: Division of Violence Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/connectingthedots.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community Health and Program Services: Health Disparities Among Racial/Ethnic Populations. Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA. 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2021 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2023. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2021, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10-expanded.html on Jan 23, 2023.

- Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). Available from URL: www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars.

- Jones SE, Ethier KA, Hertz M, et al. Mental Health, Suicidality, and Connectedness Among High School Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic — Adolescent Behaviors and Experiences Survey, United States, January–June 2021. MMWR Suppl 2022;71(Suppl-3):16–21. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su7103a3

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 1991-2019 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. Available at http://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/. Accessed on March 3, 2021.

- SAMHSA. National Survey of Drug Use and Health: Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adults [online]. 2020 [Accessed: Sep 9, 2021]. Available from URL: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2019-nsduh-lesbian-gay-bisexual-lgb-adults

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. 2022 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. 2022. Retrieved Jan 12, 2023 from https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/data.asp

- SAMHSA. National Survey of Drug Use and Health: Veteran Adults [online]. 2020. Available from URL: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt31103/2019NSDUH-Veteran/Veterans%202019%20NSDUH.pdf

- Czeisler M&, Board A, Thierry JM, et al. Mental Health and Substance Use Among Adults with Disabilities During the COVID-19 Pandemic—United States, February–March 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:1142–1149. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7034a3

- Cree RA, Okoro CA, Zack MM, Carbone E. Frequent Mental Distress Among Adults, by Disability Status, Disability Type, and Selected Characteristics—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1238–1243. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a2

- Peterson C, Sussell A, Li J, Schumacher PK, Yeoman K, Stone DM. Suicide Rates by Industry and Occupation—National Violent Death Reporting System, 32 States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:57–62. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6903a1

- Stone DM, Jones CM, Mack KA. Changes in Suicide Rates—United States, 2018–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:261–268. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7008a1