Facts about Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate

Cleft lip and cleft palate are birth defects that occur when a baby’s lip or mouth do not form properly during pregnancy. Together, these birth defects commonly are called “orofacial clefts”.

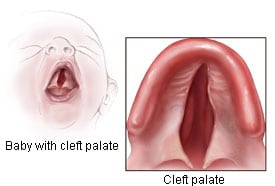

What is Cleft Lip?

The lip forms between the fourth and seventh weeks of pregnancy. As a baby develops during pregnancy, body tissue and special cells from each side of the head grow toward the center of the face and join together to make the face. This joining of tissue forms the facial features, like the lips and mouth. A cleft lip happens if the tissue that makes up the lip does not join completely before birth. This results in an opening in the upper lip. The opening in the lip can be a small slit or it can be a large opening that goes through the lip into the nose. A cleft lip can be on one or both sides of the lip or in the middle of the lip, which occurs very rarely. Children with a cleft lip also can have a cleft palate.

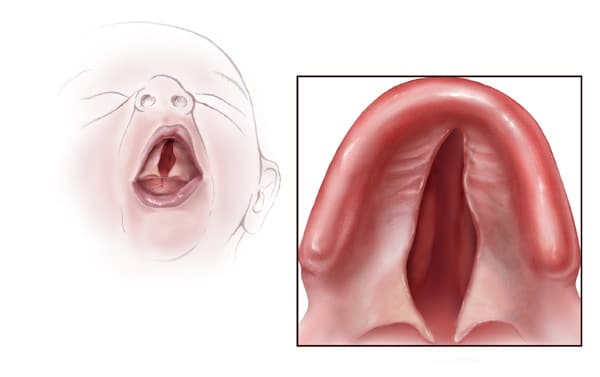

What is Cleft Palate?

The roof of the mouth (palate) is formed between the sixth and ninth weeks of pregnancy. A cleft palate happens if the tissue that makes up the roof of the mouth does not join together completely during pregnancy. For some babies, both the front and back parts of the palate are open. For other babies, only part of the palate is open.

Other Problems

Children with a cleft lip with or without a cleft palate or a cleft palate alone often have problems with feeding and speaking clearly and can have ear infections. They also might have hearing problems and problems with their teeth.

How Many Babies are Born with Cleft Lip/Cleft Palate?

- About 1 in every 1,600 babies is born with cleft lip with cleft palate in the United States.

- About 1 in every 2,800 babies is born with cleft lip without cleft palate in the United States.

- About 1 in every 1,700 babies is born with cleft palate in the United States.1

Causes and Risk Factors

The causes of orofacial clefts among most infants are unknown. Some children have a cleft lip or cleft palate because of changes in their genes. Cleft lip and cleft palate are thought to be caused by a combination of genes and other factors, such as things the mother comes in contact with in her environment, or what the mother eats or drinks, or certain medications she uses during pregnancy.

Like the many families of children with birth defects, CDC wants to find out what causes them. Understanding the factors that are more common among babies with a birth defect will help us learn more about the causes. CDC funds the Centers for Birth Defects Research and Prevention, which collaborate on large studies such as the National Birth Defects Prevention Study (NBDPS; births 1997-2011) and the Birth Defects Study To Evaluate Pregnancy exposureS (BD-STEPS; began with births in 2014), to understand the causes of and risks for birth defects, including orofacial clefts.

Recently, CDC reported on important findings from research studies about some factors that increase the chance of having a baby with an orofacial cleft:

- Smoking―Women who smoke during pregnancy are more likely to have a baby with an orofacial cleft than women who do not smoke.2-3

- Diabetes―Women with diabetes diagnosed before pregnancy have an increased risk of having a child with a cleft lip with or without cleft palate, compared to women who did not have diabetes.5

- Use of certain medicines―Women who used certain medicines to treat epilepsy, such as topiramate or valproic acid, during the first trimester (the first 3 months) of pregnancy have an increased risk of having a baby with cleft lip with or without cleft palate, compared to women who didn’t take these medicines.6-7

CDC continues to study birth defects, such as cleft lip and cleft palate, and how to prevent them. If you are pregnant or thinking about becoming pregnant, talk with your doctor about ways to increase your chances of having a healthy baby.

Diagnosis

Orofacial clefts, especially cleft lip with or without cleft palate, can be diagnosed during pregnancy by a routine ultrasound. They can also be diagnosed after the baby is born, especially cleft palate. However, sometimes certain types of cleft palate (for example, submucous cleft palate and bifid uvula) might not be diagnosed until later in life.

Management and Treatment

Services and treatment for children with orofacial clefts can vary depending on the severity of the cleft; the child’s age and needs; and the presence of associated syndromes or other birth defects, or both.

Surgery to repair a cleft lip usually occurs in the first few months of life and is recommended within the first 12 months of life. Surgery to repair a cleft palate is recommended within the first 18 months of life or earlier if possible.8 Many children will need additional surgical procedures as they get older. Surgical repair can improve the look and appearance of a child’s face and might also improve breathing, hearing, and speech and language development. Children born with orofacial clefts might need other types of treatments and services, such as special dental or orthodontic care or speech therapy.4,8

With treatment, most children with orofacial clefts do well and lead a healthy life. Some children with orofacial clefts may have issues with self-esteem if they are concerned with visible differences between themselves and other children. Parent-to-parent support groups can prove to be useful for families of babies with birth defects of the head and face, such as orofacial clefts.

References

- Mai CT, Isenburg JL, Canfield MA, Meyer RE, Correa A, Alverson CJ, Lupo PJ, Riehle‐Colarusso T, Cho SJ, Aggarwal D, Kirby RS. National population‐based estimates for major birth defects, 2010–2014. Birth Defects Research. 2019; 111(18): 1420-1435.

- Little J, Cardy A, Munger RG. Tobacco smoking and oral clefts: a meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:213-18.

- Honein MA, Rasmussen SA, Reefhuis J, Romitti P, Lammer EJ, Sun L, Correa A. Maternal smoking, environmental tobacco smoke, and the risk of oral clefts. Epidemiology 2007;18:226–33.

- Yazdy MM, Autry AR, Honein MA, Frias JL. Use of special education services by children with orofacial clefts. Birth Defects Research (Part A): Clinical and Molecular Teratology 2008;82:147-54.

- Correa A, Gilboa SM, Besser LM, Botto LD, Moore CA, Hobbs CA, Cleves MA, Riehle-Colarusso TJ, Waller DK, Reece EA. Diabetes mellitus and birth defects. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2008;199:237.e1-9.

- Margulis AV, Mitchell AA, Gilboa SM, Werler MM, Glynn RJ, Hernandez-Diaz S, National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Use of topiramate in pregnancy and risk of oral clefts. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2012;207:405.e1-e7.

- Werler MM, Ahrens KA, Bosco JL, Michell AA, Anderka MT, Gilboa SM, Holmes LB, National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Use of antiepileptic medications in pregnancy in relation to risks of birth defects. Annals of Epidemiology 2011;21:842-50.

- American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association. Parameters for evaluation and treatment of patients with cleft lip/palate or other craniofacial anomalies. Revised edition, Nov 2009. Chapel Hill, NC. P. 1-34. https://acpa-cpf.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Parameters_Rev_2009_9_.pdf