|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

| Weekly |

| January 13, 2006 / 55(01);1-5 |

|

|

|

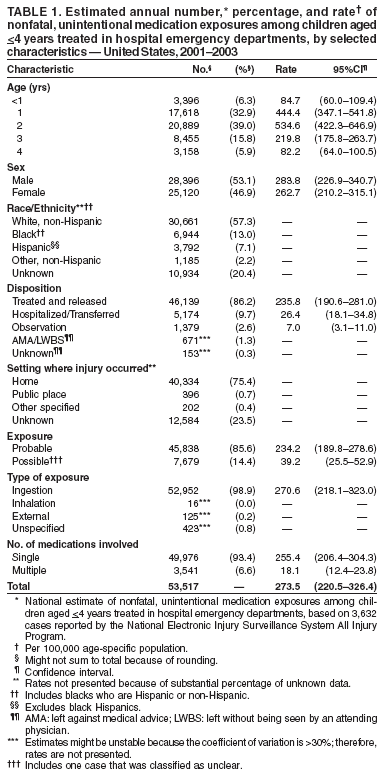

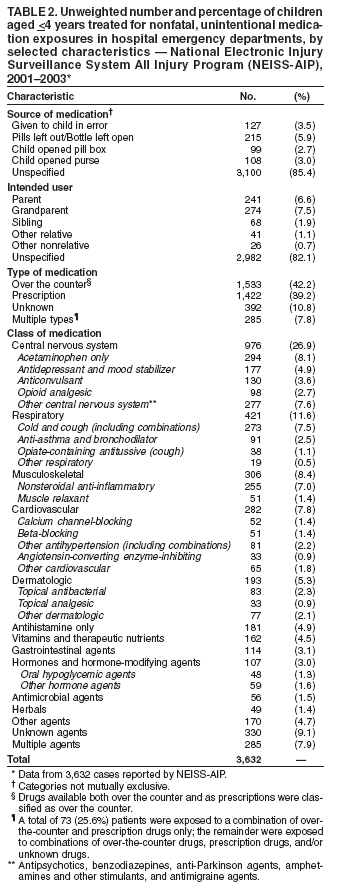

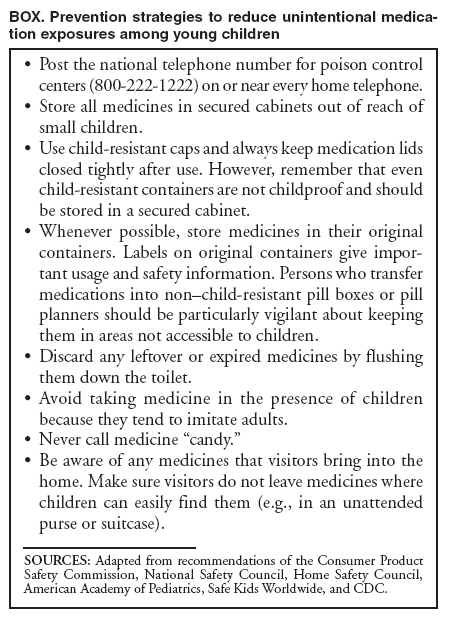

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Nonfatal, Unintentional Medication Exposures Among Young Children --- United States, 2001--2003Young children are vulnerable to inadvertent exposure to prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) medications, especially when these items are not stored securely. In 2002, according to death certificate data, 35 children aged <4 years died from unintentional medication poisonings in the United States (CDC, unpublished data, 2005). In 2003, according to reports to U.S. poison control centers, pharmaceuticals accounted for 1,336,209 (55.8%) of unintentional chemical or substance exposures (1). Of those pharmaceutical exposures, 568,939 (42.6%) involved children aged <6 years. For this report, CDC analyzed 2001--2003 data from hospital emergency department (ED) visits reported by the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System--All Injury Program (NEISS-AIP). The results of this analysis indicated that, during 2001--2003, an estimated 53,517 children aged <4 years were treated annually in U.S. EDs for unintentional medication exposures. An estimated 72% of these exposures were in children aged 1--2 years. Children aged <4 years can reach items on a table, in a purse, or in a drawer, where medications are often stored; young children also tend to put objects they find in their mouths (2). Parents and others responsible for supervising children should store medications securely at all times, keep them out of the reach of children, and be vigilant in preventing access by children to daily-use containers such as pill boxes. NEISS-AIP is operated by the Consumer Product Safety Commission and collects data on all types and causes of injuries in patients treated in hospital EDs (3). Data are collected from a nationally representative subsample of 66 of the 100 NEISS hospitals that were selected as a stratified probability sample of hospitals in the United States and its territories. NEISS-AIP provides data on approximately 500,000 injury-related and consumer-product--related cases each year. Cases were defined as those involving children aged <4 years treated at a NEISS-AIP hospital ED for nonfatal, unintentional exposures to medications, including all types of prescription and OTC medications. Cases involving only illicit drugs or alcohol were excluded. Cases resulting from the adverse effects of therapeutic use of medications, medical errors (e.g., misprescribed by doctor or pharmacist), or drug exposure of infants from maternal drug use during pregnancy or breastfeeding also were excluded. A brief narrative abstracted from the medical record was used to code, where possible, the route of exposure (e.g., ingestion, inhalation, or external contact), likelihood of exposure (i.e., probable or possible [one case was classified as unclear]), source of medication (e.g., pill box or purse), intended user (e.g., grandparent or parent), and class of medication. Each case was assigned a sample weight based on the inverse of the probability of selection (3); these weights were summed to provide national estimates of nonfatal medication exposures. Estimates were based on weighted data for 3,632 patients aged <4 years treated at NEISS-AIP hospital EDs for medication exposures during 2001--2003. Confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using a direct variance estimation procedure that accounted for the sample weights and complex sample design. Rates were calculated using U.S. Census bridged-race population estimates for 2001--2003 (4). Because the sources and intended users of the medications were identified only for a small percentage of the cases and because most national estimates for individual classes of medications might be unstable (i.e., coefficient of variation >30%), NEISS-AIP data for these three case characteristics are unweighted and cannot be used as national estimates. During 2001--2003, an estimated 53,517 (95% CI = 43,166--63,868) children aged <4 years were treated annually in EDs for nonfatal, unintentional medication exposures, an annual rate of 273.5 per 100,000 age-specific population (CI = 220.5--326.4) (Table 1). Children aged 1 year and 2 years had the highest rates (444.4 and 534.6, respectively) and accounted for 72.0% of medication exposure cases. Nearly one in 10 children (9.7%) were hospitalized or transferred for specialized care for their medication exposure. The majority of the cases occurred in the home (75.4%). Among the medication exposures, 85.6% were classified as probable; 98.9% of the exposures resulted from ingestion. The source of the medication was not specified for 3,100 (85.4%) of the NEISS-AIP cases, and the intended user was not specified for 2,982 (82.1%). On the basis of unweighted data, the most common sources of medication exposure were pills left out or pill bottles left open, which was reported in 215 (5.9% ) cases (Table 2). Other incidents involved medications administered in error by a parent or caregiver (3.5%) and children opening pill boxes (2.7%) or purses (3.0%). Among cases with intended users identified, the medications were intended most commonly for use by the child's grandparent (7.5%) or parent (6.6%). Exposures from OTC medications (42.2%) were slightly more common than from prescription medications (39.2%). Among the approximately 92% of cases for which the class of medication could be identified, the most common medications were central nervous system agents (e.g., acetaminophen or antidepressants) (26.9%), respiratory agents (e.g., cough and cold or anti-asthma agents) (11.6%), and musculoskeletal agents (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents or muscle relaxants) (8.4%). Other common classes were cardiovascular agents (7.8%), dermatologic agents (e.g., topical antibacterial or analgesic agents) (5.3%), antihistamines (4.9%), and vitamins and therapeutic nutrients (4.5%). Prescription medications accounted for 67% of admissions to hospitals or transfers for specialized care. Among those agents specified, the most common medication classes involved in hospital admissions or transfers were anticonvulsant agents (9.6%), calcium-channel--blocking agents (6.8%), antidepressant and mood-stabilizing agents (6.2%), and oral hypoglycemic agents (6.2%). Reported by: A Burt, JL Annest, PhD, Office of Statistics and Programming, MF Ballesteros, PhD, Div of Unintentional Injury Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; DS Budnitz, MD, Div of Healthcare Quality Promotion, National Center for Infectious Diseases, CDC. Editorial Note:Data in this report indicate that, during 2001--2003, an estimated 53,517 children aged <4 years were treated in U.S. hospital EDs each year for unintentional exposure to prescription and OTC medications. Consistent with previous studies (5,6), most of these exposures occurred in the home among children aged 1--2 years. Certain exposures involved common household medications such as acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, cold and cough preparations, and vitamin and mineral supplements. Some of these agents can be highly toxic (e.g., acetaminophen or opiod analgesics), and ingestion by young children can lead to death (6). Children aged <4 years treated in EDs for medication exposures were nearly four times as likely to be hospitalized or transferred for specialized care as children in this age group treated for all unintentional causes of injury (9.7% versus 2.5%) (7). During the last 3 decades, emphasis on preventing unintended medication exposures has reduced the number of deaths from childhood poisonings (8). Multiple factors likely have contributed to this decline, including improved packaging, product substitutions and reformulations, education programs, accessibility of poisoning information, and treatment advances (8). Child-resistant packaging, mandated by the Poison Prevention Packaging Act of 1970, has been credited with reducing prescription medication deaths in children aged <4 years by 45% from 1974 to 1992 (9). Despite the progress in reducing the number of fatal poisonings, unintentional medication exposures remain a serious threat to the health of young children. Data from this report indicate that, in 2002, approximately 1,500 ED visits and 150 hospital admissions or transfers from EDs occurred for each of the 35 fatalities reported among children aged <4 years. National data on fatal and nonfatal medication exposures should be used to set prevention priorities and develop interventions. Although requirements for child-resistant packaging are mandated by the Poison Prevention Packaging Act, this study determined that at least 12% of ED visits for medication exposures resulted from children gaining access to medications left in the open, in pill boxes, or in purses. Because medication users often transfer medications from their original child-resistant containers to other containers for daily use, manufacturers are encouraged to improve container designs and promote strategies that allow convenient access for the intended user while also protecting children. The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, NEISS-AIP provides only national estimates of unintentional medication exposures and not state or local estimates. Second, NEISS-AIP provides data only for patients treated in hospital EDs and does not include children treated in outpatient settings or not treated at all. Finally, narratives abstracted from medical records provided information regarding the source of the medication and the intended user for only 15% and 18% of the cases, respectively; for the remaining cases, the source and intended user of the medication were unknown. Continued promotion of established prevention measures can help reduce morbidity and mortality from unintentional medication exposures (Box). However, to help develop new prevention strategies and assess their effectiveness in reducing the most common and most severe incidents among young children, additional data on the incident circumstances, specific medications involved, and patient outcomes are needed. More complete incident information will be available through the recently implemented NEISS Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance project (NEISS-CADES), which collects detailed information (e.g., drug dosage, laboratory testing, and clinical treatment) on all types of adverse drug events, including unintentional drug ingestions by children (10). Acknowledgments This report is based, in part, on data contributed by T Schroeder, MS, C Irish, and other staff members, Division of Hazard and Injury Data Systems, Consumer Product Safety Commission. References

Table 1  Return to top. Table 2  Return to top. Box  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Date last reviewed: 1/12/2006 |

|||||||||

|