|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

| Weekly |

| November 9, 2001 / 50(44);984-6 |

|

|

|

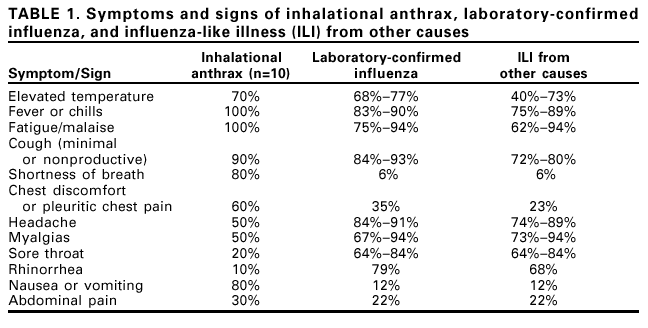

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Notice to Readers: Considerations for Distinguishing Influenza-Like Illness from Inhalational AnthraxCDC has issued guidelines on the evaluation of persons with a history of exposure to Bacillus anthracis spores or who have an occupational or environmental risk for anthrax exposure (1). This notice describes the clinical evaluation of persons who are not known to be at increased risk for anthrax but who have symptoms of influenza-like illness (ILI). Clinicians evaluating persons with ILI should consider a combination of epidemiologic, clinical, and, if indicated, laboratory and radiographic test results to evaluate the likelihood that inhalational anthrax is the basis for ILI symptoms. ILI is a nonspecific respiratory illness characterized by fever, fatigue, cough, and other symptoms. The majority of ILI cases is not caused by influenza but by other viruses (e.g., rhinoviruses and respiratory syncytial virus [RSV]), adenoviruses, and parainfluenza viruses). Less common causes of ILI include bacteria such as Legionella spp., Chlamydia pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Influenza, RSV, and certain bacterial infections are particularly important causes of ILI because these infections can lead to serious complications requiring hospitalization (2--4). Yearly, adults and children can average one to three and three to six ILI, respectively (5). Epidemiologic ConsiderationsTo date, 10 confirmed cases of inhalational anthrax have been identified (1). The epidemiologic profile of these 10 cases caused by bioterrorism can guide the assessment of persons with ILI. All but one case have occurred among postal workers, persons exposed to letters or areas known to be contaminated by anthrax spores, and media employees. The 10 confirmed cases have been identified in a limited number of communities. Inhalational anthrax is not spread from person-to-person. In comparison, millions of ILI cases associated with other respiratory pathogens occur each year and in all communities. Respiratory infections associated with bacteria can occur throughout the year; pneumococcal disease peaks during the winter, and mycoplasma and legionellosis are more common during the summer and fall (4). Cases of ILI resulting from influenza and RSV infection generally peak during the winter; rhinoviruses and parainfluenza virus infections usually peak during the fall and spring; and adenoviruses circulate throughout the year. All of these viruses are highly communicable and spread easily from person to person. Clinical ConsiderationsAlthough many different illnesses might present with ILI symptoms, the presence of certain signs and symptoms might help to distinguish other causes of ILI from inhalational anthrax. Nasal congestion and rhinorrhea are features of most ILI cases not associated with anthrax (Table 1) (6,7). In comparison, rhinorrhea was reported in one of the 10 persons who had inhalational anthrax diagnosed since September 2001. All 10 persons with inhalational anthrax had abnormal chest radiographs on initial presentation; seven had mediastinal widening, seven had infiltrates, and eight had pleural effusion. Findings might be more readily discernable on posteroanterior with lateral views, compared with anteroposterior views (i.e., portable radiograph alone) (1). Most cases of ILI are not associated with radiographic findings of pneumonia, which occurs most often among the very young, elderly, or those with chronic lung disease (2,3). Influenza associated pneumonia occurs in approximately 1%--5% of community-dwelling adults with influenza and can occur in >20% of influenza-infected elderly (2). Influenza-associated pneumonia might be caused by the primary virus infection or, more commonly, by bacterial infection occurring coincident with or following influenza illness (2). TestingNo rapid screening test is available to diagnose inhalational anthrax in the early stages. Blood cultures grew B. anthracis in all seven patients with inhalational anthrax who had not received previous antimicrobial therapy. However, blood cultures should not be obtained routinely on all patients with ILI symptoms who have no probable exposure to anthrax but should be obtained for persons in situations in which bacteremia is suspected. Rapid tests for influenza and RSV are available, and, if used, should be conducted within the first 3--4 days of a person's illness when viral shedding is most likely. RSV antigen detection tests have a peak sensitivity of 75%--95% in infants but do not have enough sensitivity to warrant their routine use among adults (8). Among the influenza tests available for point-of-care testing, the reported sensitivities and specificities range from 45%--90% and 60%--95%, respectively (9). Two tests (Quidel Quickvue Influenza test and ZymeTx Zstatflu test®) can be performed in any physician's office, and three are classified as moderately complex tests (Biostar FLU OIA; Becton-Dickinson Directigen Flu A+B; and Becton-Dickinson Directigen Flu A™). The clinical usefulness of rapid influenza tests for the diagnosis of influenza in individual patients is limited because the sensitivity of the influenza rapid tests is relatively low (45%--90%), and a large proportion of persons with influenza might be missed with these tests. Therefore, the rapid influenza tests should not be done on every person presenting with ILI. However, rapid influenza testing used with viral culture can help indicate whether influenza viruses are circulating among specific populations, (e.g., nursing home residents or patients attending a clinic). This type of epidemiologic information on specific populations can aid in diagnosing ILI. Vaccination against influenza is the best means to prevent influenza and its severe complications. The influenza vaccine is targeted towards persons aged >65 years and to persons aged 6 months to 64 years who have a high risk medical condition because these groups are at increased risk for influenza-related complications. The vaccine also is targeted towards health-care workers to prevent transmission of influenza to high-risk persons. In addition, vaccination is recommended for household members of high-risk persons and for healthy persons aged 50--64 years. The vaccine can prevent 70%--90% of influenza infections in healthy adults. However, the vaccine does not prevent ILI caused by infectious agents other than influenza, and many persons vaccinated against influenza will still get ILI. Therefore, receipt of vaccine will not definitely exclude influenza from the differential diagnosis of ILI or increase the probability of inhalational anthrax as a cause, especially among persons who have no probable exposure to anthrax. Frequent hand washing can reduce the number of respiratory illnesses (10) and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine can reduce the risk for serious pneumococcal disease. Additional information about anthrax is available at <http://www.hhs.gov/hottopics/healing/biological.html> and < ttp://www.bt.cdc.gov/DocumentsApp/FactsAbout/FactsAbout.asp>. Additional information about influenza, RSV and other viral respiratory infections, and pneumococcal disease is available at <http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/diseases/flu/fluvirus.htm>, <http://www.cdc.gov/nip/flu/default.htm>, <http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/revb/index.htm>, <http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dbmd/diseaseinfo/streppneum_t.htm>, and <http://www.cdc.gov/nip/diseases/Pneumo/vac-chart.htm>. References

Table 1  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 11/13/2001 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 11/13/2001

|